Our paper showing global and general effects of land use on zoonotic host communities is out today in @nature! There’s quite a lot in the paper, so I thought I’d do an explainer of the findings. 1/ https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-020-2562-8">https://www.nature.com/articles/...

First off, massive thanks to my amazing coauthors @David_W_Redding @ProfKateJones @tnewbold31 @TimBlackburn66 @KaiqingC and Christl Donnelly - this has been in the pipeline for a few years.

Zoonoses are diseases caused by pathogens that are naturally carried by animals, and that regularly or occasionally transmit (‘spillover’) to people – think plague, SARS-CoVs, Ebola, leishmaniasis, Lyme disease… 3/

Land use changes – such as deforestation and agricultural expansion – impact wildlife communities and bring people into contact with wildlife, and so are often identified as drivers of zoonotic spillover risk. 4/

But it’s hard to understand how general these effects might be, as human-altered landscapes do lots of things that influence disease transmission: they impact wildlife, but also reshape hydrology, introduce livestock, increase human densities… 5/

So we zoomed in on one specific aspect: does human land use lead to global, general impacts on populations and communities of zoonotic hosts (wildlife species that are host to zoonotic pathogens)? 6/

There are reasons to expect this may be the case: human disturbance tends to act as a kind of filter on ecological communities, with most species being lost, but some more human-tolerant species persisting or thriving (think rats, sparrows, foxes…) 7/

Some studies have suggested species that are more resilient might often also be better hosts of pathogens – if this is the case, we might expect zoonotic hosts to be more likely to persist in human-dominated ecosystems. 8/

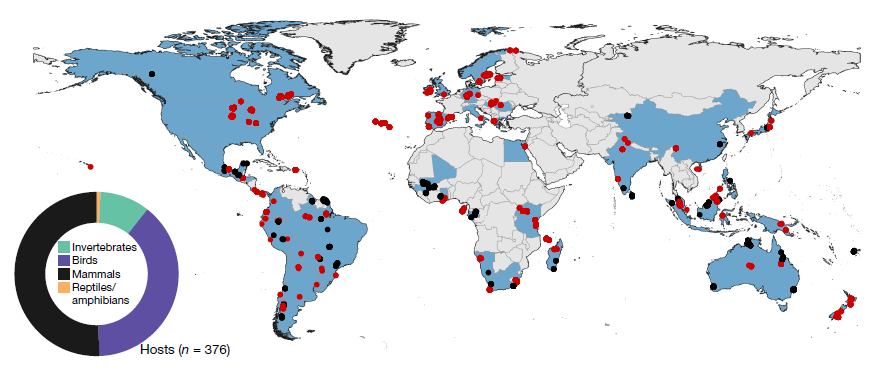

To test this we analysed an amazing database of 6,801 sites worldwide (h/t #PREDICTSproject @AndyPurvisNHM), which we combined with data on host-pathogen interactions to identify zoonotic hosts 9/

However, many species are really under-researched, and could carry pathogens we don’t know about. So to account for this, all of our analyses included simulations of how going out and surveying under-studied species might impact the results. 10/

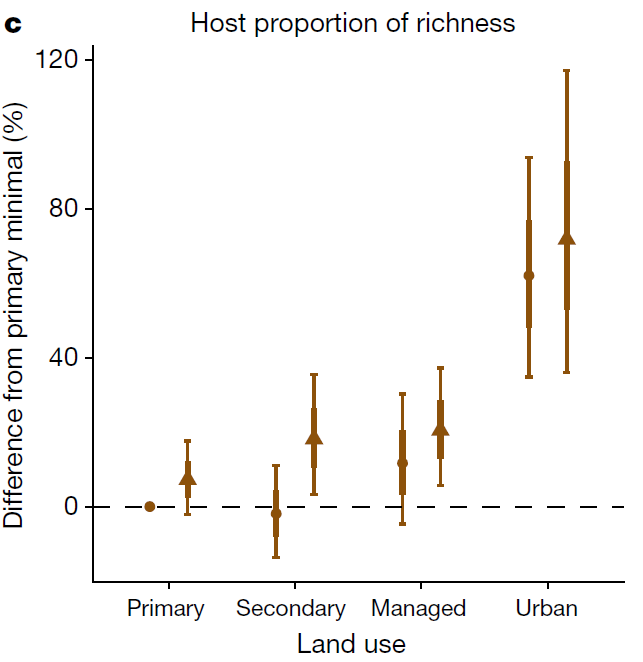

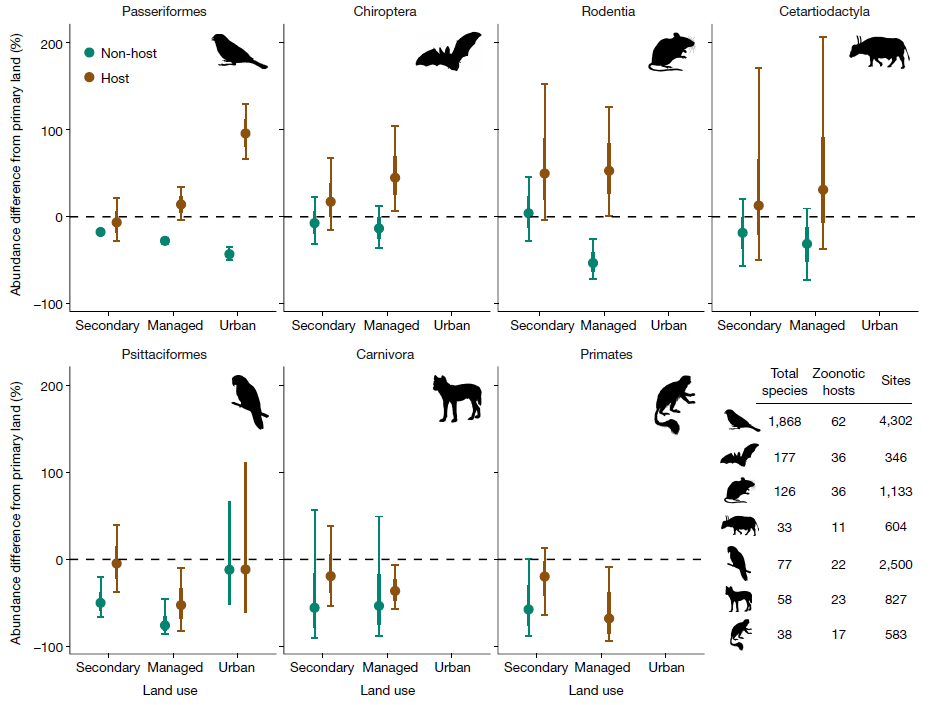

We found that, under higher intensities of human land use, an increasing proportion of the species and individuals in wildlife communities are known zoonotic hosts (whereas non-hosts show general declines – the ‘filter-like& #39; effect I mentioned earlier). 11/

But this depends on the species grouping: we see clear divergence between host and non-host species in rodents, bats and passerine (perching) birds, but not in primates or carnivores 12/

But...  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🤔" title="Denkendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Denkendes Gesicht"> couldn’t these trends simply be caused by historical opportunities for contact (and pathogen-sharing) between people and those more human-tolerant species, rather than anything intrinsically biological? 13/

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🤔" title="Denkendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Denkendes Gesicht"> couldn’t these trends simply be caused by historical opportunities for contact (and pathogen-sharing) between people and those more human-tolerant species, rather than anything intrinsically biological? 13/

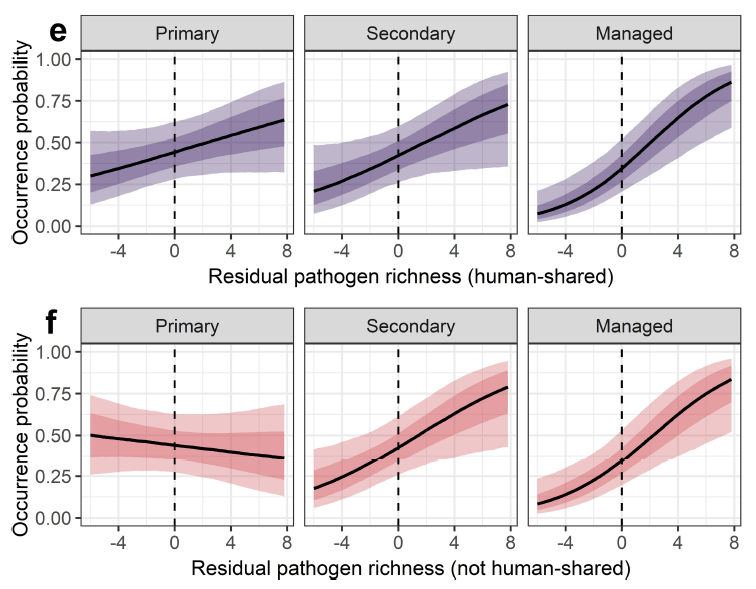

We reasoned that, if species biological traits were contributing to this worldwide pattern, we would expect to see more positive responses to land use in species that carry more pathogens *overall* (regardless of whether they’re zoonotic). 14/

So we tested this, and that’s what we found: mammal species that either carry more human-shared *or* more wildlife-only pathogens are more likely to occur in human-managed habitats. 15/

This suggests species traits are playing a role. For example, species with a ‘fast-living’ strategy (investing energy in rapid reproduction) are often more tolerant of human disturbance, and are thought to often invest less in adaptive immune defense. 16/

So what does this all mean in terms of risk to people? It’s important to stress that risk of zoonotic spillover is influenced by lots of factors – not just the host community. 17/

Indeed, so many of the factors that influence whether people are vulnerable to disease and epidemics are socioeconomic (as illustrated in US COVID context by @edyong in this amazing article https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2020/09/coronavirus-american-failure/614191/)">https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/... 18/

But our findings show a global context: that habitat loss, agricultural and urban change are driving general changes in ecological hazards for zoonotic spillover. 19/

They suggest we need to be strengthening health systems, diagnostics and surveillance in fast-changing, agricultural and urbanizing areas, to improve abilities to rapidly detect and treat emerging infections. 20/

There are also I think broader Qs about ultimate drivers of land change & links to env. justice – e.g., much of agri expansion/biodiversity loss in more disease-vulnerable regions is driven by external economic pressures/demand. n/ https://www.nature.com/articles/s41561-020-0592-3">https://www.nature.com/articles/...

Thanks for reading! If you found any of this interesting, the paper is on the Nature site, or feel free to contact me for a copy https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-020-2562-8">https://www.nature.com/articles/...

And thanks to Richard Ostfeld and Felicia Keesing for their great commentary on the study in @nature https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-02189-5">https://www.nature.com/articles/...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter