This is @PieterCoppens8 again, tweeting about my research on Jamal al-Din al-Qasimi this week. Let me share a case study on Qasimi today, on which I wrote an article that will be published in MIDEO in 2021. (1/16)

One of the things that struck me in te tafsir of Qasimi is his huge introduction on the fundamentals (usul) of the genre, which was still very unusual in that time. When I dug deeper into his publications and started reading his letter correspondence, (2/16)

I realized that discovering and publishing usul literature in general, not only on tafsir, but also on fiqh and hadith, was something he was deeply invested in. Why? (3/16)

I think it is related to the calls to ijtihad (independent reasoning) that was typical for him and his circle. If one wishes to practice ijtihad in any knowledge discipline, knowledge of the usul of that discipline is required after all. (4/16)

These works on usul were no longer widely spread, known or discussed in the post-classical Islamic tradition in Damascus in the 19th century however. They were hardly part of the educational curriculum, not even on the highest level, and library culture had become so... (5/16)

meagre that such treatises were not self-evidently part of the intellectual horizon of local scholars. Qasimi hoped that a focus on uṣul would lead to a greater sense of unity among different schools and would make an end to useless quarrels on secondary matters. (6/16)

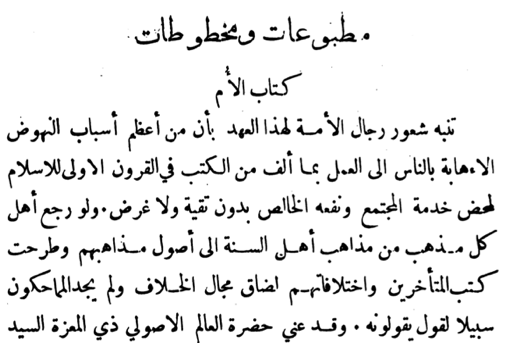

In 1906, the Damascene journal al-Muqtabas, written by Qasimi& #39;s close friend Muhammad Kurd Ali, opened a review of the first printed edition of Shafi’ī’s Kitāb al-umm with the statement that: (7/16)

"the minds of the men of this umma of this age have come to realize that from among the grandest causes of revival (nuhūd) is (...) to work on the books written in the first centuries of Islam, to purely be of service to society, and to be to its use sincerely, (8/16)

without hidden motives or goals. Would the people of every school (madhhab) of the people of the Sunna only return to the fundamentals (usūl) of their schools, and toss the books of the later generations with all their differences of opinion, (9/16)

then the domain of differences would become much narrower, and wranglers would no longer find a way to say what they say."

Another example is a letter from Mustafa al-Ghalayini to Qasimi, in which he states: (10/16)

Another example is a letter from Mustafa al-Ghalayini to Qasimi, in which he states: (10/16)

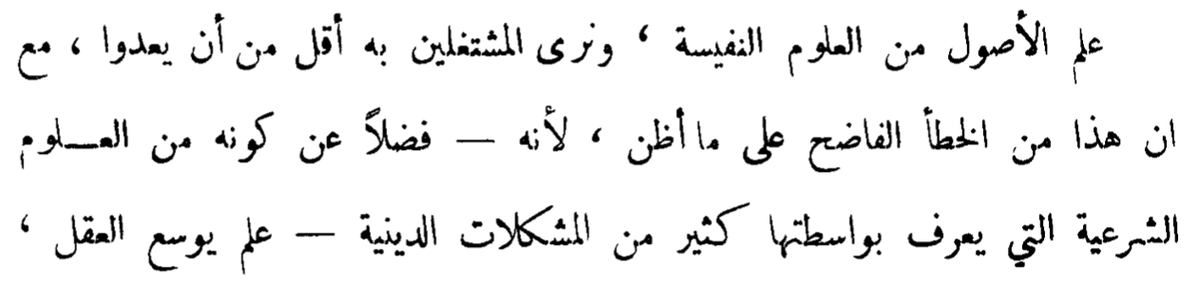

"The knowledge discipline of uṣūl is precious. Those occupied with it are too few to count. This is a severe mistake in my opinion, because -aside from belonging to the Islamic knowledge disciplines through which many religious problems are known-

(11/16)

(11/16)

it is a knowledge discipline that is mind-expanding, enlightens the intellect, and considers mankind too high for pure emulation. I think that only a group that does not understand this knowledge discipline correctly at all rules that emulation (taqlīd) is obligatory." (12/16)

Qasimi therefore published a series of often forgotten treatises on usul al-fiqh, usul al-tafsir, and wrote a work on the fundamentals of the science of Hadith. His goal, I believe, was empowerment of a new class of scholars, both locally as transregionally, (13/16)

to engage with the Islamic primary sources directly, and to make these sources relevant for a larger audience than just the small clique of Islamic scholars that conserved their position within society through their monopoly on religious knowledge and education. (14/16)

One could say that to be able to engage in iǧtihād, Qāsimī and his peers first had to undertake another form of iǧtihād: broadening the intellectual horizon by rediscovering these forgotten classics. (15/16)

This was a two-sided process for Qāsimī: on the one hand travelling and corresponding with friends abroad to collect new prints available from mainly India and Egypt; on the other hand, rediscovering long forgotten manuscripts, teaching, editing, printing, spreading them. (16/16)

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter