Just submitted a revised version of a book chapter on fatness and late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century visual and material culture, focusing on representations Daniel Lambert, so I thought I& #39;d do a wee thread on it.

(Not least because some of the issues it raises are pertinent for recent moralising discussions around fatness and its negative portrayal in light of coronavirus).

The chapter starts by emphasising the importance of thinking about visual and material culture when discussing historical fatness, using images of Albinia Hobart, Countess of Buckinghamshire (1737/8-1816) to do so

Referencing Hobart’s attendance at public events, her gambling habit, & her canvassing on behalf in the Westminster Election of 1784, Hobart& #39;s satirical representations draw rather staid comparisons betwn fatness & moral laxity.

Many play on her dual noticeability, as not only physically highly present due to her overweight body, but ideologically so, thanks to her intrusions into the public sphere of the theatre, politics, and fashionable life.

Yet images of Lambert disrupt narratives around fatness in eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century art and objects as rooted solely in its pejorative associations.

Instead, in the case of Lambert fatness and its representation worked to construct identity and celebrity; facilitated commercial activities for Lambert himself; and even decorated people’s homes in the form of collectable and desirable images and objects.

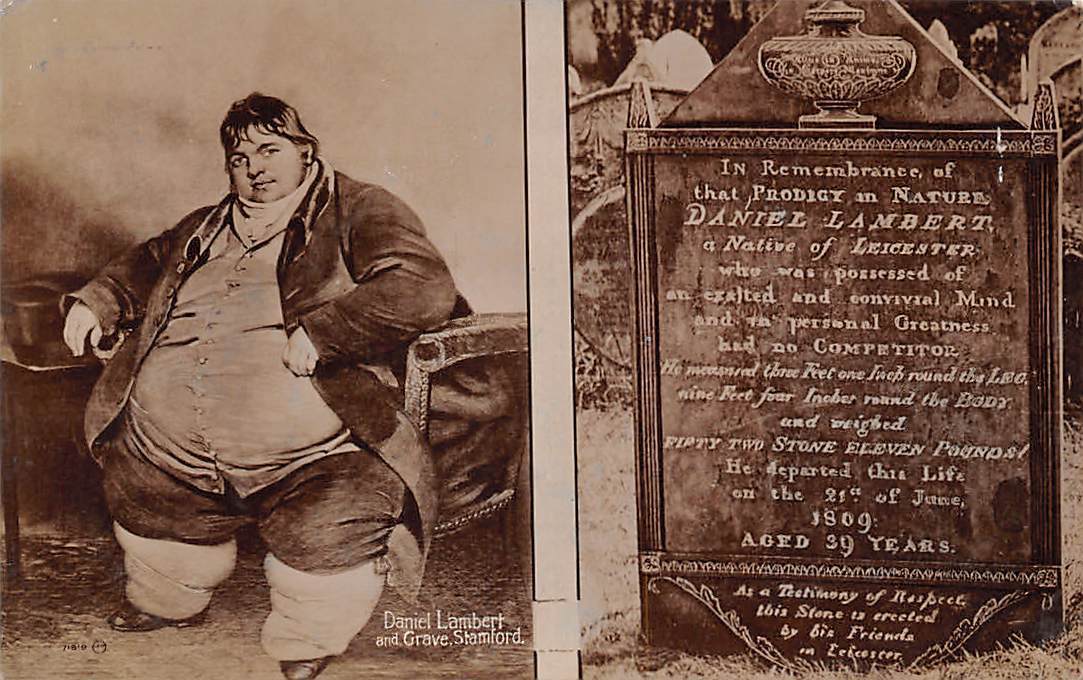

Lambert, a Bridewell Prison keeper and animal breeder, was famous for the large size of his body, which earned him the moniker of England’s heaviest man. Born in Leicester in 1770, by the time Lambert was 23 he apparently weighed 32 stone, and by 1805 he weighed 50.

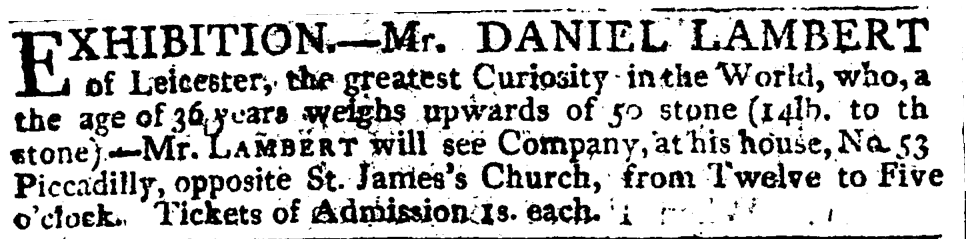

Following the prison’s closure in 1805, Lambert was granted an annuity of £50, which he supplemented with income generated from the sale of hunting dogs and fighting cocks, and by publicly exhibiting himself in London.

Here, Lambert found great fame, becoming a popular attraction for the fashionable London elite. After eventually tiring of the city, Lambert returned to Leicester in 1806, where he lived as a relatively wealthy man and continued to breed animals until his death in 1809.

In accordance with his fame, Lambert was depicted by portraitists and other artists numerous times throughout his life, resulting in a repetitive visual culture in which aspects of his physical likeness were emphasized until they formed a specifically recognisable silhouette.

The precedent for this visual rhetoric is undoubtedly the portrait of Lambert painted by Benjamin Marshall (1768-1835), created some time around 1807.

Lambert’s visual culture also seems to have been influenced and codified through his portrayal within a second, anonymous portrait, likely painted around the same time

What is remarkable about the portrait is not so much the image itself, which, like Marshall’s painting, eschews distracting details in favour of a focus on Lambert’s body, but the innumerable copies that exist of it, both in painted and printed forms.

Housed at various regional galleries around Lincolnshire, Leicestershire, Northampton, and at the Wellcome Collection, the works reinforce Lambert’s cultural currency as a figure whom a large audience desired to see represented.

This consumer-base eager for images of Lambert is likewise reinforced by the large print culture that emerged around him, which often stuck closely to the archetypes provided by the two model portraits above.

This commodification of Lambert was to endure well into the nineteenth century which saw a change from a visual culture of commemoration to a material one, with Lambert increasingly depicted in objects such as ceramics, metalware, and on small printed consumable objects

Around this time Lambert also seems to have become a reference point for the production of a series of inkwells in both salt-glaze ceramic and brass, the latter of which appears to have been mass-produced in notable quantity, given the number that survive today.

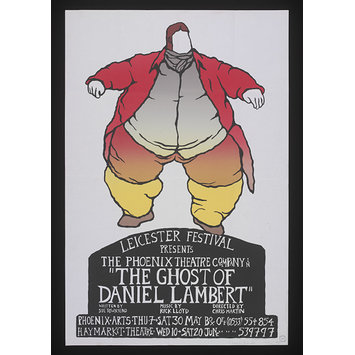

This transformation of body into icon is exemplified by the faceless outline of Lambert that was used as advertising for the Leicester Festival’s performance of the production ‘The Ghost of Daniel Lambert’ in the 1980s.

The poster demonstrates how, even a century later, Lambert’s seated pose & large body maintained their emblematic status.

In Fat is a Feminist Issue, Susie Orbach firmly established the relationship between the image and the idea of the ‘perfect’ female body, arguing for a damaging correlation between a glossy visual culture depicting only the thinnest, and women’s conceptions of their own bodies.

Although 2018 marked the 40th anniversary of this important meditation on the problematic position of the media’s presentation of the body, negative attitudes towards the fat body and its representations remain prevalent.

This was exemplified by reactions to the UK edition of Cosmopolitan magazine in October of that same year, which featured the plus-size model and influencer Tess Holliday on its front cover, a choice that drew vicious criticism.

Showing Holliday wearing a green swimsuit, the cover portrayed her as an unapologetically fat woman, her body representing a deliberately arresting visual intrusion into a space usually reserved for ‘conventionally attractive’ bodies.

Yet despite its revolutionary presence on the front cover of a mainstream fashion magazine, depictions of fat celebrities, particularly positive ones, have a long and complex history, as attention to Lambert’s own visual and material histories can attest.

Lambert is obviously an exception. His representations are vexed - not straightforwardly positive or negative in tone.

But the diverse nature of these visual and material cultures, their popularity, and their commercial potential, complicate narratives of fat bodies as unredeemably undesirable that are enduringly ingrained within society.

While wanting to avoid meaningless presentism, current narratives around fatness have long roots, in which various forms of visual communication have been key.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter