Thread about how the soundscape of late Renaissance French was a lot more varied than the linear handbook summaries lead one to imagine. With audio and visuals .

Wanting to see how Louise Labé& #39;s poetry would sound as pronounced by a 16th century Lyonnaise I looked at the testimony of Louis Meigret, born in the first decade of the sixteenth century in Lyon.

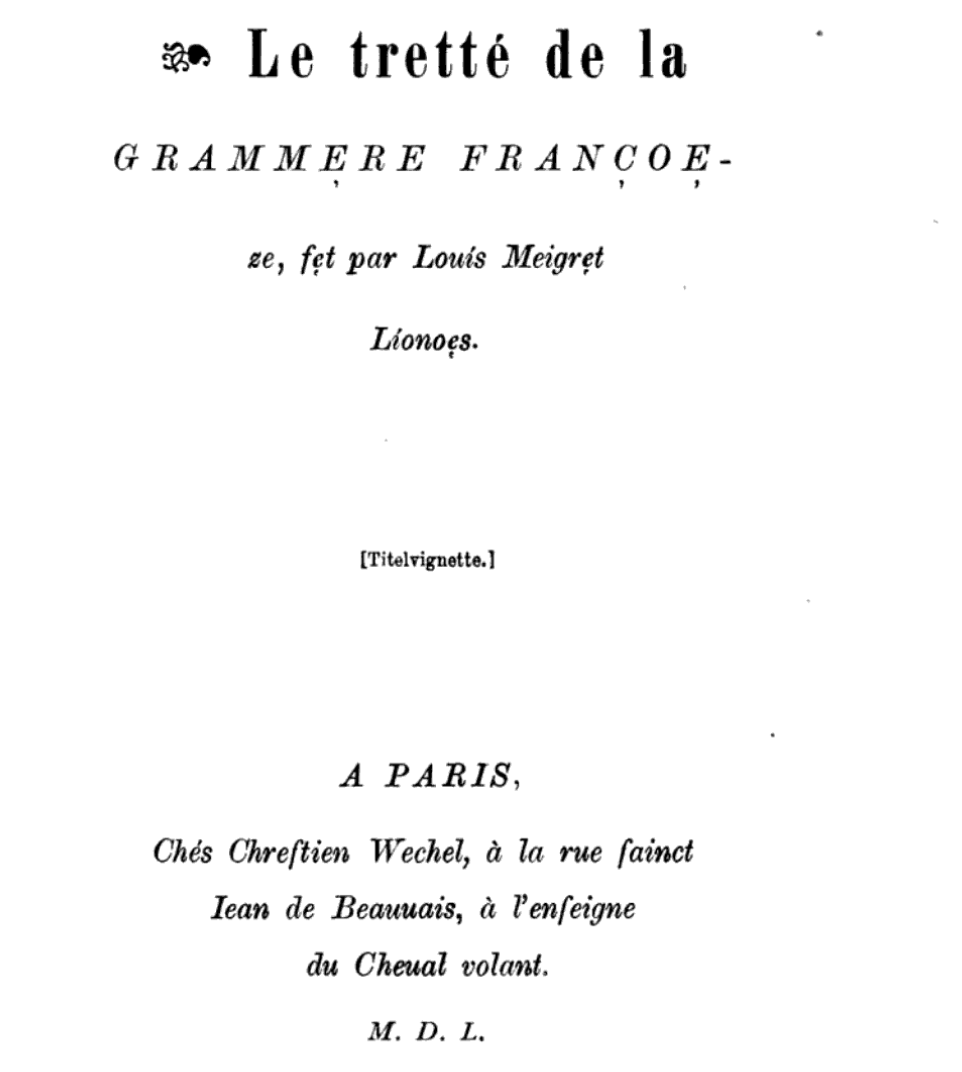

Meigret was a learned man who lived in the same town and at the same time as Labé, and gifted us with the first grammar of French ever written by a Frenchman. Like his London contemporary John Hart, he wrote his book entirely in a reformed spelling meant to represent his speech.

From the criticisms of some of his contemporaries — and from the larger history of Francian — we learn something that gets erased from the standard histories of the French language that portray it as a lineal development radiating out from Paris.

Meigret& #39;s French is clearly not ancestral to modern Standard French. He represented features of what was apparently Lyonnais pronunciation, giving us an indication that regional variations in pronunciation were not only alive but were felt fit for representation in a grammar.

His pronunciation is clearly provincial from the perspective of his Parisian critics, but the fact that he documented it at all has interesting implications.

One may be assured that he would not have represented this type of pronunciation if it were felt uncouth in the circles he moved in. The man was aware of differences in speech among Picards, Parisians etc. He probably COULD if he wished have represented Parisian pronunciation.

He not only felt no need to do so, but chastizes Parsians for the phonological vice of overnasalized vowels. https://twitter.com/azforeman/status/1290131340172627968">https://twitter.com/azforeman...

I honestly had a little trouble believing Meigret was describing what he seemed to be describing in some ways. If he had not shown himself an extremely capable observer of speech, it would be reasonable to assume (as some have) that he was failing to accurately report things.

But it& #39;s unlikely someone careful enough to observe so many (demonstrably) real peculiarities and archaisms in his speech would drop the ball by failing to note the existence of a centralized /ǝ/, or a three-way contrast in rounded back vowels.

It will not do to suggest Meigret is simply failing to report the expected features of a dialect that he clearly wasn& #39;t even trying to describe.

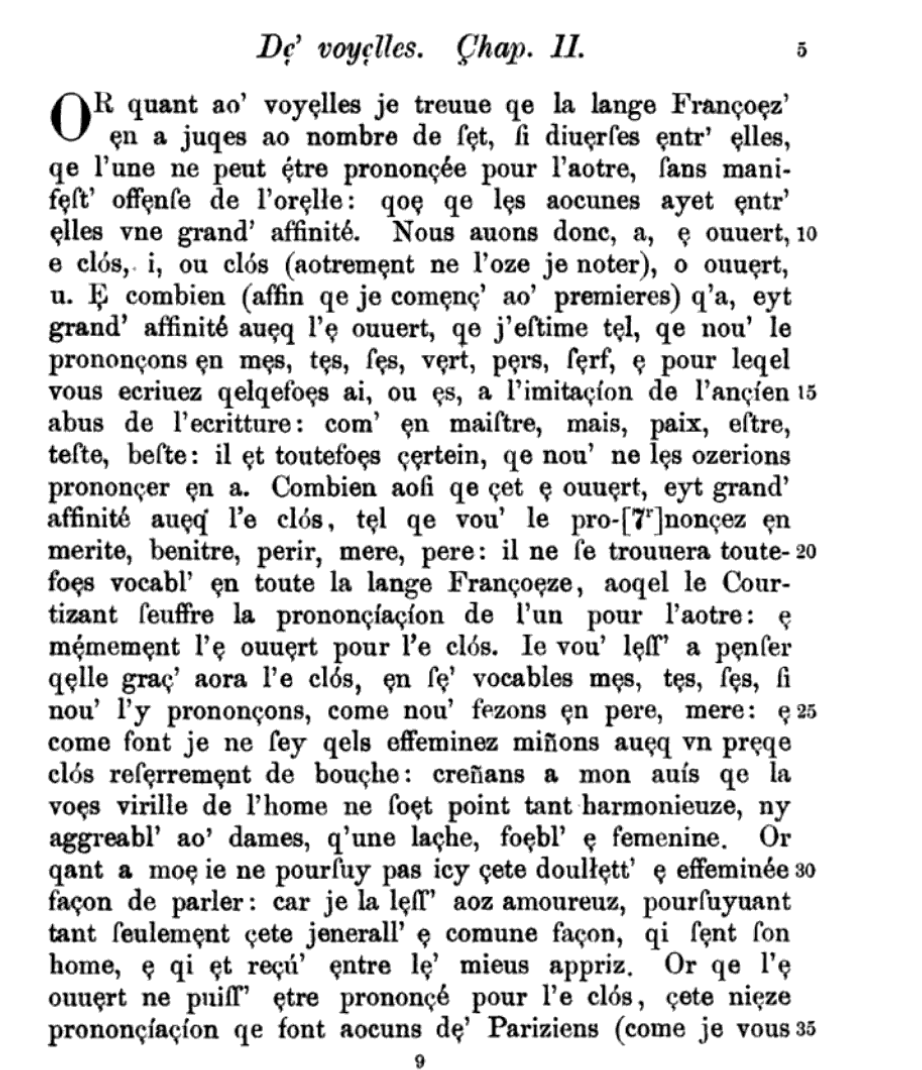

One of the biggest whoppers is that Meigret& #39;s "e muet" is neither "muet" nor /ǝ/. It isn& #39;t a centralized vowel at all, contrary to the reports of other French phoneticians of the period. It& #39;s hard for me to accept that he didn& #39;t hear what he says he heard.

Part of the reason is that he is very insistant about this, and accuses his adversary Péletier (who advocated a more recognizably Parisian-type norm) of bullshitting for suggesting that a third type e-vowel must be represented.

There are other curiosities. For example, his "o clos" occurs in both <nos> and <nous> (which are for him homophones) but is also high enough to be equated with /u/ by his adversaries who chide the Lyonnese and other Meridionals for saying things like <chouse> for <chose>.

As I tried reading French out in Meigret& #39;s accent, the first thing that I was reminded of was Indian English, Southwestern Irish English, various forms of African French and other colonial linguistic situations.

If I am to believe Meigret about what his speech is like — and I can see no real reason not to— it means that some form of Lyonnese French in the mid-16th century had a mixture of two things.

First, there is a remarkable conservatism for the period (preservation of old French diphthongs). Second (and forgive me for getting feely and inductivist here — I& #39;m just tweeting), what I am tempted to call a "foreign-seeming accent".

I mean "foreign-seeming" in the same sense that a native speaker of Indian English might be naively (and quite insultingly) assumed to be an L2 English-learner by people ignorant of the fact that there are native Anglophones who talk that way.

The context for such a speech arising doesn& #39;t seem all that hard to guess at: French was adopted by the elite of Lyons a century or so previous, while the local dialect of Arpitan probably continued to be spoken alongside it.

Apart from the fact that Meigret seems to have pronounced the post-tonic <e> in much the way that an Italian might pronounce the <e> in <amore>, what strikes me is the intimations of a rather distinctive speech-prosody.

In particular, stress for Meigret seems to be positively associated with length. This is strongly implied by his attempt to describe what makes the non-shwa "e feminine" distinctive. See, for Meigret, the word for "father" <pere> had /e/ (not /ɛ/) in the tonic syllable.

And Meigret is clearly sensitive to (and adamant about) the fact that the unstressed <e> is distinguished from the stressed <e> simply by length. Of course, he hears what he says he hears, but it seems the reason for the sortness in the final <e> is that it is post-tonic.

When position of word-accent is bound up with phonetic vowel-duration in this manner, that implies things about speech prosody. I know I& #39;m on a limb here. But it suggests a prosody different from that of a modern Parisian jibbering "en cul de poule".

More perhaps like standard Catalan, or some traditional Occitan dialects that have not had their prosody Gallicized. The type of prosody that sits uneasily between "syllable-timed" and "stress-timed" (with the useful function of reminding us that that binary is bullshit).

Alright before I go on, here& #39;s me reading a sonnet by Meigret& #39;s contemporary Louise Labé in my tentative reconstruction of his accent. If I sound silly, it& #39;s up to you to judge whether that& #39;s Meigret& #39;s fault or mine. https://soundcloud.com/alex-foreman-209218576/louise-labe-sonnet-viii-read-in-16th-century-lyonnese-pronunciation-per-meigret">https://soundcloud.com/alex-fore...

I kind of suspect post-tonic vowels may have been simply adopted wholesale as /e/ when the Lyonnese elite switched to French, without any reduction. (Lyonnese Arpitan today tolerates all kinds of posttonic vowel distinctions that French is too phonotactically flabby to handle).

Let me note again that Meigret is very proud of his speech it seems, and has no insecurity whatsoever about it. He in fact holds Parisian phonology in something less than high regard. There is zero indication that this accent was unacceptable in polite or elite company.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter