#TheCompleteBeethoven #343

Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67 (1804-8)

1/ "Well, so be it; for you, poor Beethoven, there is no outward happiness; you must create it within you." - Ludwig van Beethoven, 1808. https://youtu.be/lNtb-ly1I_k ">https://youtu.be/lNtb-ly1I...

Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67 (1804-8)

1/ "Well, so be it; for you, poor Beethoven, there is no outward happiness; you must create it within you." - Ludwig van Beethoven, 1808. https://youtu.be/lNtb-ly1I_k ">https://youtu.be/lNtb-ly1I...

2/ Beethoven& #39;s words refer to a perceived slight by his friend Baron Ignaz von Gleichenstein, dedicatee of the Op. 69 Cello Sonata, completed that same year. They could also be a programme for his new symphony, finally finished after 4 years of struggle. https://twitter.com/deeplyclassical/status/1289941959113453568?s=20">https://twitter.com/deeplycla...

3/ A revolutionary symphony whose first four notes changed the course of classical music forever.

But wait.

"Create it within you"?

"Four years of struggle"?

"Revolutionary symphony"?

Is Symphony No. 5 really so original, or did Beethoven pinch its best ideas from Haydn?

But wait.

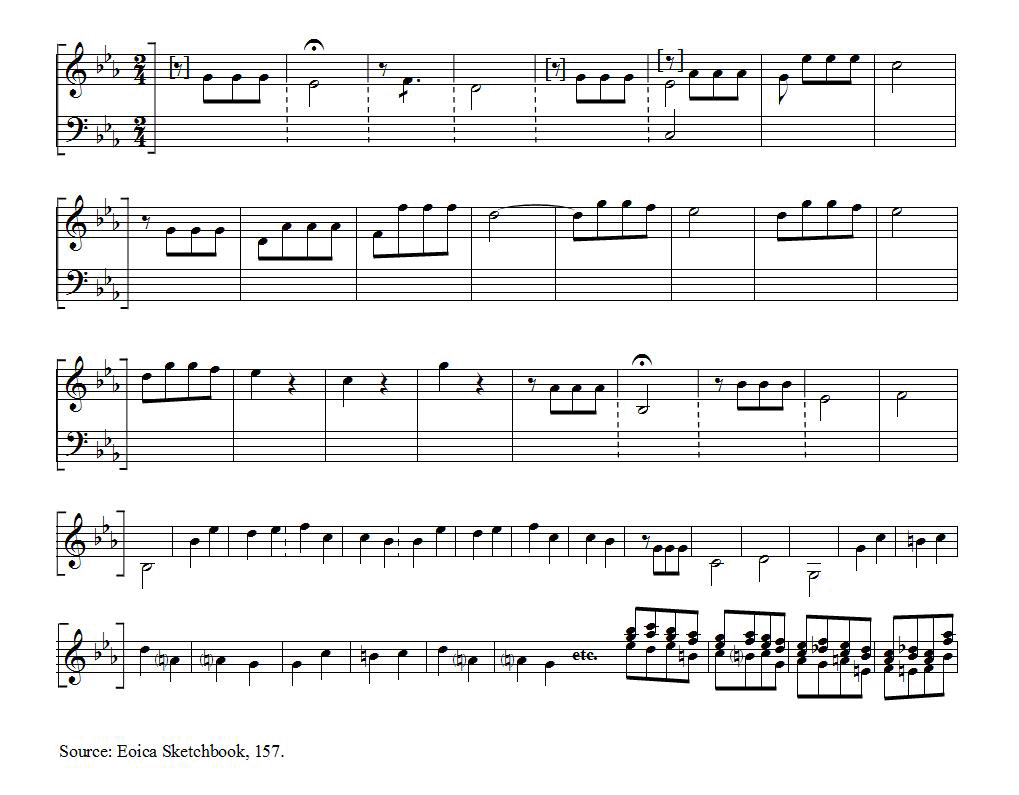

"Create it within you"?

"Four years of struggle"?

"Revolutionary symphony"?

Is Symphony No. 5 really so original, or did Beethoven pinch its best ideas from Haydn?

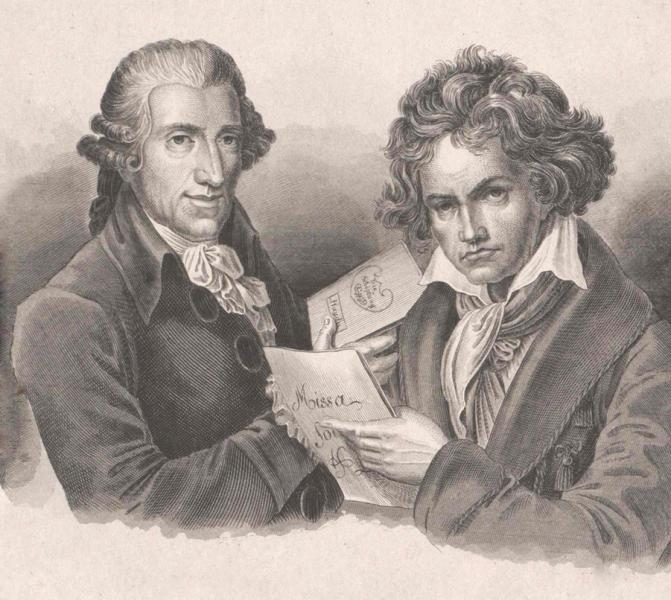

4/ "I never learned anything from Haydn." Really?

A symphonic journey from troubled C minor to C major triumph?

Haydn& #39;s been there. He began teaching Beethoven upon his return from London to Vienna in 1792 with this new symphony in his luggage. https://youtu.be/gVpXPG9DhmA ">https://youtu.be/gVpXPG9Dh...

A symphonic journey from troubled C minor to C major triumph?

Haydn& #39;s been there. He began teaching Beethoven upon his return from London to Vienna in 1792 with this new symphony in his luggage. https://youtu.be/gVpXPG9DhmA ">https://youtu.be/gVpXPG9Dh...

5/ A C minor third movement with a cello-centric trio?

Haydn& #39;s done that. Hell, he did that in the same damn symphony. To be fair, Beethoven does use all of them rather than only one, and he makes the double basses sweat too.

Haydn& #39;s done that. Hell, he did that in the same damn symphony. To be fair, Beethoven does use all of them rather than only one, and he makes the double basses sweat too.

6/ A symphony that brings back the the third movement in the middle of the finale?

Haydn& #39;s got the T-shirt. He had his printed back in 1772. In No. 46 (one of my Top 10 Haydn symphonies) the music of the minuet (14:57) gatecrashes the finale at 19:48. https://youtu.be/sSYDiieCSSk ">https://youtu.be/sSYDiieCS...

Haydn& #39;s got the T-shirt. He had his printed back in 1772. In No. 46 (one of my Top 10 Haydn symphonies) the music of the minuet (14:57) gatecrashes the finale at 19:48. https://youtu.be/sSYDiieCSSk ">https://youtu.be/sSYDiieCS...

7/ As for music developed from a single four-note repeated-note motif? Well, once you start chasing examples of that in Haydn& #39;s symphonies, your hunt will never be over. https://youtu.be/_D-qYgydTSY ">https://youtu.be/_D-qYgydT...

8/ It& #39;s day-job time. Tomorrow, more on the influences that went into this symphony, and why ultimately they don& #39;t matter.

"Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal" - T. S. Eliot.

"Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal" - T. S. Eliot.

9/ "A good composer does not imitate; he steals.” - Igor Stravinsky

Beethoven& #39;s slow movement is in double variation form, a form Haydn practically invented (some say he stole it from C. P. E. Bach) and used in no fewer than six symphony slow movements. ">https://youtu.be/WV4HJrQF4...

Beethoven& #39;s slow movement is in double variation form, a form Haydn practically invented (some say he stole it from C. P. E. Bach) and used in no fewer than six symphony slow movements. ">https://youtu.be/WV4HJrQF4...

10/ For over 200 years the Fifth Symphony been the musical icon of Beethoven& #39;s popular image as the Romantic renegade breaking with the past, but his musical revolution is founded firmly on the traditions of the Classical style handed down to him by his teacher, "Papa" Haydn.

11/ But revolutionary it certainly is. As every musical renegade knows, you can overthrow the establishment by the simplest of means if you can create a really good C minor mood. More on how Beethoven went about storming the barricades tomorrow. https://youtu.be/4o0r9unT4L4 ">https://youtu.be/4o0r9unT4...

12/ "I always see Beethoven as having been influenced by Haydn. Yet he started a revolution - not just to be different, but also because he lived in a revolutionary era." @andris_nelsons

In early 1804, Beethoven finished a revolutionary symphony. https://twitter.com/deeplyclassical/status/1268058724872183812?s=20">https://twitter.com/deeplycla...

In early 1804, Beethoven finished a revolutionary symphony. https://twitter.com/deeplyclassical/status/1268058724872183812?s=20">https://twitter.com/deeplycla...

13/ “The Eroica adumbrated a story of a hero’s victory and the blessings he brings the world; it conveyed that narrative in complex forms and a welter of ideas." - Jan Swafford.

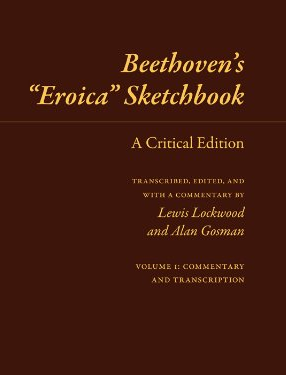

Beethoven& #39;s "Eroica" sketchbook also contains ideas for two movements of a C minor "Sinfonia."

Beethoven& #39;s "Eroica" sketchbook also contains ideas for two movements of a C minor "Sinfonia."

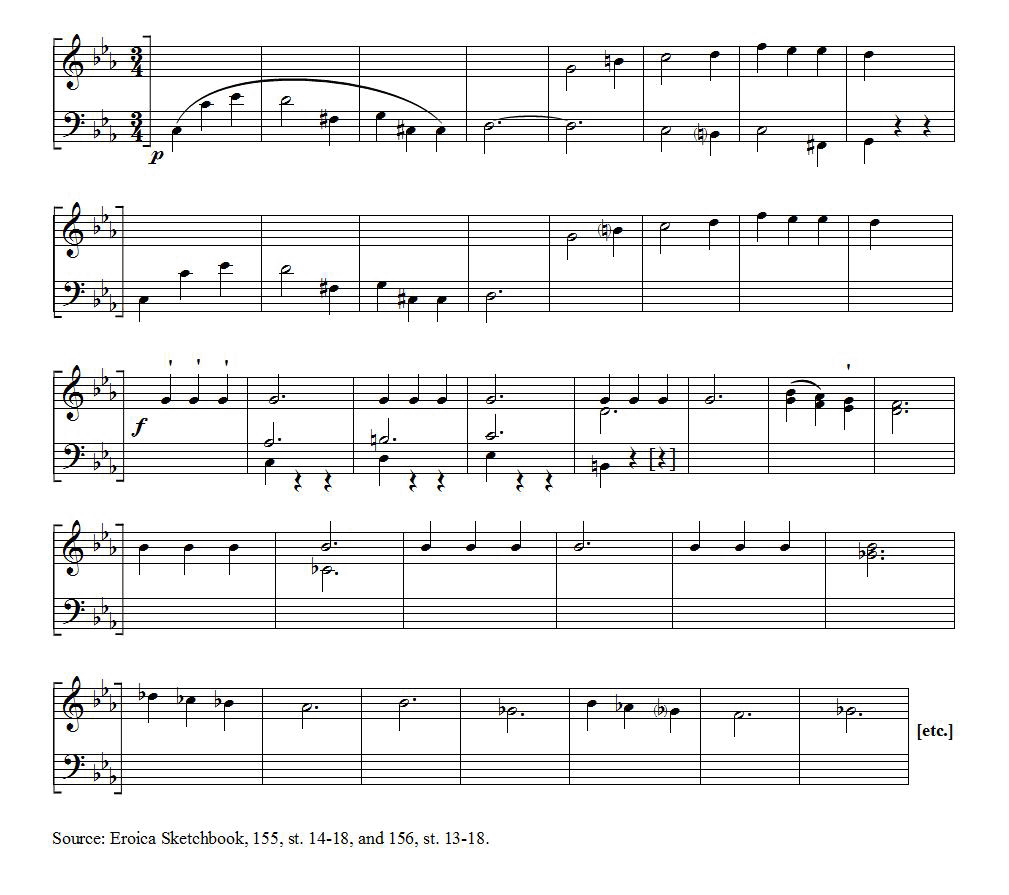

14/ First, there is a concept sketch of the main themes of the scherzo and trio. It is followed by a sketch for the exposition of the first movement. The themes are all remarkably close to their final forms. There is no sign yet of the slow movement or finale.

15/ Did the symphony& #39;s initial inspiration come, as inspiration had so often come before, from Beethoven& #39;s beloved Mozart? Some commentators see the scherzo theme as a transformed quotation of the finale to Mozart& #39;s symphony, K. 550. What do you think? ">https://youtu.be/p8bZ7vm4_...

16/ More sketches, probably from summer 1804, show further work on the first movement and the first ideas for the second, a slow movement you could dance to. There& #39;s a version of the main theme notated in 3/4 and labelled "Andante quasi Menuetto", followed by a "quasi Trio".

17/ The "quasi Trio" material strikingly resembles an idea originally sketched for the Second Symphony, but discarded. Its contours foreshadow the second theme of the Fifth& #39;s slow movement, right down to the four-note "da-da-da-duuum" motif in slowed down triple metre.

18/ The 1804 sketches also contain ideas for a finale far from the triumphant one we all know. The Eroica sketchbook& #39;s Presto fragment, starting softly and expanding, is in C minor. Who ends two of their three C minor symphonies that way?

You Know Who. ">https://youtu.be/BUgUo_468...

You Know Who. ">https://youtu.be/BUgUo_468...

19/ Beethoven may first have planned a work that followed in the footsteps of the Sturm und Drang symphonies by Haydn and Mozart. But he ends his sketches with a seed that, when it grew, transformed the 5th into much, much more:

"It could close at the very end with a March."

"It could close at the very end with a March."

20/ Only a few later sketches survive. There must be many more lost in the mists of time. We know that he set the symphony aside for long periods to work on other projects but from now on our view of Beethoven& #39;s progress towards the finished work is frequently enveloped in fog.

21/ While the symphony lay dormant for up to 2 years, its musical ideas did not. By the time Beethoven resumed work on the first movement in 1806, its 4-note fate motif had already knocked on the door and gained entry into his Appassionata sonata (0:46). https://twitter.com/deeplyclassical/status/1276039436443308033?s=20">https://twitter.com/deeplycla...

22/ On the opposite sketchbook page from the earliest ideas for the symphony are sketches for the G major Piano Concerto. The rhythm of its opening bars have a strong family likeness to the 4 notes of "the most famous theme in the world" (George Grove). https://twitter.com/deeplyclassical/status/1278210375750684678?s=20">https://twitter.com/deeplycla...

23/ Beethoven& #39;s most famously "revolutionary" symphony may (or may not) share musical DNA with his most famously "conservative" symphony. In 1806 Beethoven set the C minor symphony aside yet again in order to dash off the work that was to be his 4th. https://twitter.com/deeplyclassical/status/1282559228281081861?s=20">https://twitter.com/deeplycla...

24/ His "traditional" B-flat symphony included one decidedly innovative feature: the scherzo and trio are repeated, expanding the conventional three parts to five. The idea, already used in the last of his Op. 33 Bagatelles, recurs in Symphonies 6 and 7. https://twitter.com/deeplyclassical/status/1254654949692264449?s=20">https://twitter.com/deeplycla...

25/ Beethoven originally intended the 5th Symphony& #39;s scherzo to have the same five-part structure. However, close study of the autograph score and the earliest copies and parts show that Beethoven cancelled the repeat, reverting to the traditional three-part A-B-A form.

26/ What follows is truly revolutionary. In "one of the dramatic masterstrokes of orchestral music" (Tom Service), a coda of spine-tingling mystery links the scherzo directly to the finale. The same idea occurs in one of the Razumovsky quartets of 1806. https://twitter.com/deeplyclassical/status/1278578132904300545?s=20">https://twitter.com/deeplycla...

27/ Beethoven goes a step further in the other symphony he was writing between 1804 and 1808, where the last three movements unfold in one continuous span. It& #39;s impossible to say where the inspiration first struck for this unprecented coup de théâtre. https://youtu.be/iQGm0H9l9I4 ">https://youtu.be/iQGm0H9l9...

28/ It& #39;s also uncertain when and how Beethoven arrived at his new conception of the finale, but by 1807 the march, only glimpsed as an afterthought in 1804, had obliterated the original C minor sketches. Tragedy had been transformed into triumph. https://youtu.be/kHYBoG7hiZk ">https://youtu.be/kHYBoG7hi...

29/ "The Fifth tells a story of personal victory and inner heroism, painted in broad strokes on an epic canvas. The ecstasy at the Eroica’s end is humanity rejoicing. The ecstasy at the end of the Fifth Symphony is a personal cry of victory." (Jan Swafford)

30/ The transition from the scherzo heralds a finale that transmutes Beethoven& #39;s earlier innovations into a musical revolution that "transports the listener& #39;s imagination on to a higher plane of experience, encompassing and going beyond all that has passed." (Lewis Lockwood)

31/ But what kind of revolution is it? Are the Fifth& #39;s material and sound world derived from the "Éclat triomphale" of the French Revolution? Were Beethoven& #39;s first sketches inspired by Cherubini? John Eliot Gardiner and @mco_london certainly think so. https://youtu.be/T_TbMmV0OgU ">https://youtu.be/T_TbMmV0O...

32/ To truly grasp the scale, scope and depth of the musical revolution that Beethoven brings out, we have to dig deeper into the music itself, which means it& #39;s analysis time! I& #39;ll use this performance as my reference. There will be timings! https://youtu.be/fuPrcnpIRx8 ">https://youtu.be/fuPrcnpIR...

33/ "The first movement creates its tumultuous organic chemistry of interrelationships from the atomic particles of the notes it started with; in different guises, the four-note rhythmic idea permeates the rest of the symphony" (Tom Service)

We& #39;d better start there then (0:17)

We& #39;d better start there then (0:17)

34/ Ask anyone to sing some Beethoven and the first four notes of the Fifth are what you& #39;re likely to hear. They& #39;re not only Beethoven& #39;s motto, they& #39;re the signature tune of classical music itself, but they& #39;re only part of an opening statement that& #39;s really three motifs in one.

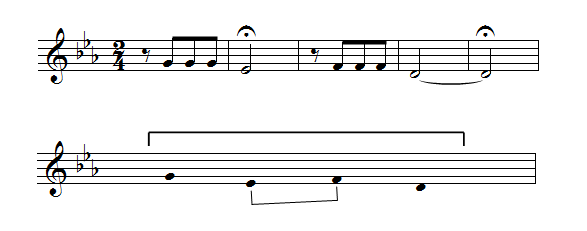

35/ One of history& #39;s great #MusicalMoustaches, celebrated music theorist Heinrich Schenker observed that the opening four-note unit is the first half of an eight-note pair. The first effect of this double statement is to generate a third motif, a rising step from E-flat to F.

36/ Beethoven added an extra bar to the second long note at the last minute to emphasize that the opening is two units, not one. Five bars, eight notes, and already he& #39;s packed in three motifs. How& #39;s that for "power, concentration and white-hot compression" (Tom Service)?

37/ These five bars are unsettling in other ways. What key are they in? The Eroica& #39;s E-flat major? Is this an introduction, or has the allegro already begun?

"the music starts with a wild outburst of energy but immediately crashes into a wall." - Michael Steinberg

"the music starts with a wild outburst of energy but immediately crashes into a wall." - Michael Steinberg

38/ They end on ambiguous harmony, demanding resolution. Only with the third statement (0:24) is Beethoven& #39;s most famous C-minor mood established. The first movement repeats and develops the four-note motif with a single-minded obsession far beyond anything in Haydn.

39/ The first subject (0:23-57) is nothing but da-da-da-dum, spreading across the entire orchestral texture. Turned upside-down, it& #39;s the second subject& #39;s bass line (1:01). It forces its energy into the melody (1:19) and re-establishes its identity (1:27) to end the exposition.

40/ The horn fanfare announcing the second subject (0:57) connects the E-flat-to-F rising step, divided by a pause in the opening, to form a recognizable motif. Once the second subject appears in the development (3:30) the step motif takes on a mysterious life of its own (3:40).

41/ Gradually losing its upward step, it& #39;s recognizable as the stuff of the unnerving calm (3:49-4:08) preceding the recapitulation. It marches into the coda (5:55), quickening its step (5:59) to rush towards the abyss. And does it also turn upside-down at the end (6:27-6:34)?

42/ Otherwise the first movement is drenched from head to toe in da-da-da-dum. The second (7:25) is at first an oasis of calm after the storm, but those four notes soon start to permeate it too. First they hang on the the first theme& #39;s tail, played at two speeds at once (7:55).

43/ A new version starts the second theme (8:17) too. All on one note, it& #39;s the scherzo theme (17:29) before the timpani reduces it to pure rhythm (24:05). Commentators including Antony Hopkins and Donald Tovey claim these resemblances are accidental. I say it& #39;s all deliberate.

44/ “That journey from despair to victory was Beethoven’s own … The Eroica exalts a conquering hero as bringer of a just and peaceful society. The Fifth proclaims every person’s capacity for heroism under the buffeting of life, a victory open to all humanity as individuals.”

45/ Let& #39;s plot the journey from C minor despair and anguish to heroic C major& #39;s eventual triumph. The battle begins (0:18) before Beethoven& #39;s C minor mood is even established.

"Tonally the opening motif is also ambiguous, poised uneasily between major and minor" - Barry Cooper

"Tonally the opening motif is also ambiguous, poised uneasily between major and minor" - Barry Cooper

46/ The openings [of Beethoven& #39;s heroic-style movements] are treated not as stable departure points that may be moved away from (and returned to) but as destabilized states that can only move forward. The initial tonic is either not firmly established ... or else destabilized."

47/ The Fifth does both. Ferocious rhythmic energy drives the allegro& #39;s C minor (0:23) relentlessly onward, never resting in the home key but always resolving on the crest of a wave of destabilizing harmony (0:33, 0:53) from which it must plunge into ever more turbulent waters.

48/ C major first asserts itself in the recapitulation (4:58), exactly where you& #39;d expected it in a classical sonata form, only to be quickly washed away (5:10). It tries again more forcefully (5:23) but its resistance is crushed under the boot of the C minor coda (5:40).

49/ But C major is not so easily vanquished. It returns with reinforcements in the andante. Brass and timpani (all tuned in C) try three times to establish a bridgehead (8:35, 10:24, 12:59) but are repelled (twice by da-da-da-dum in the bass) after failing to cadence in C major.

50/ C major finally succeeds in establishing itself for a sustained passage in the trio of the scherzo (21:51-22:52). Crucially, this is the first passage in the entire symphony where the fateful four-note motif does not appear, unless you count the timpani (22:27).

51/ If Beethoven had kept the repeat of the scherzo, C major would have been heard twice. Is that why he kept changing his mind? Either way, with C major finally on the field of battle, and da-da-da-dum pounding on distant drums (24:05), the stage is set for an epic finale.

52/ "Many assert that every minor piece must end in the minor. Nego! ...Joy follows sorrow, sunshine—rain." - Beethoven

The Eroica threw open the gates leading from the classical towards the Romantic. The 5th& #39;s finale marches triumphantly through them into a brave new world.

The Eroica threw open the gates leading from the classical towards the Romantic. The 5th& #39;s finale marches triumphantly through them into a brave new world.

53/ The finale (24:39) launches with a fresh coup de théâtre. Its opening blaze of glory is reinforced by three trombones, the first time they have been heard in the entire symphony.

"Although not three timpani, it will make more noise than six timpani, and better noise."

"Although not three timpani, it will make more noise than six timpani, and better noise."

54/ It& #39;s often asserted that Beethoven& #39;s Fifth is the first use of trombones in symphonic music (even by Barry Cooper in the @Baerenreiter edition), but this is wrong.

Twice.

This symphony, premiered in May 1807, uses three trombones in every movement. https://youtu.be/I3i8ygi0QH0 ">https://youtu.be/I3i8ygi0Q...

Twice.

This symphony, premiered in May 1807, uses three trombones in every movement. https://youtu.be/I3i8ygi0QH0 ">https://youtu.be/I3i8ygi0Q...

55/ Beethoven couldn& #39;t have known Swedish composer Joachim Eggert& #39;s symphony, but the Fifth isn& #39;t even the first time audiences heard trombones in a Beethoven symphony. There are two in the Pastoral, played first when the two works were premiered together on December 22nd 1808.

56/ Beethoven throws in a piccolo for good measure. Some commentators (but not Cooper) also claim that this was an innovation, but Joseph Haydn& #39;s brother Michael was using them in symphonies more than 40 years before, and he may not be the first. https://youtu.be/v80s4yjSdQM ">https://youtu.be/v80s4yjSd...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter

![46/ The openings [of Beethoven& #39;s heroic-style movements] are treated not as stable departure points that may be moved away from (and returned to) but as destabilized states that can only move forward. The initial tonic is either not firmly established ... or else destabilized." 46/ The openings [of Beethoven& #39;s heroic-style movements] are treated not as stable departure points that may be moved away from (and returned to) but as destabilized states that can only move forward. The initial tonic is either not firmly established ... or else destabilized."](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EfMwNVQWAAA0AYd.jpg)