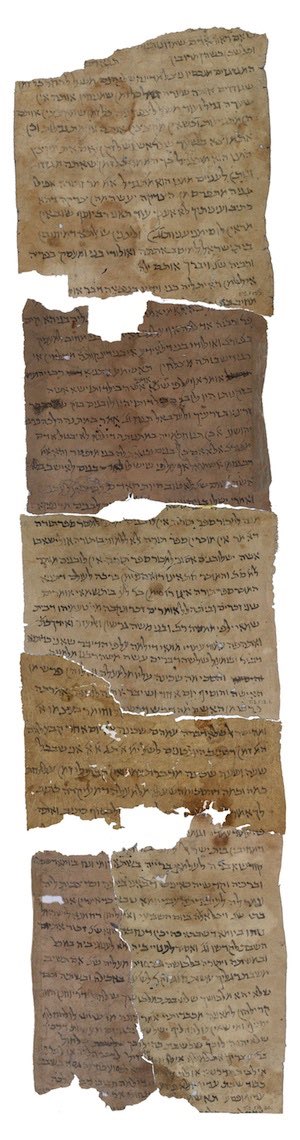

For your #fragmentfriday (tho’ I‘m vaguely aware it’s Sunday): a long vertical scroll (rotulus) from the #cairogeniza with an equally long social history. A winding thread: I’ll tell the story backwards, pts. 1-7 are modern, pts. 8-23 medieval:

1/This fragment comes from the Lewis-Gibson collection, now owned by Oxford and Cambridge. They jointly acquired these 1700 mss in a model of cooperation under the leadership of @richove of @bodleianlibs and @annejarvispul of @theUL (now of @PULibrary). https://www.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/news/2013/historic-rivals-join-forces-to-save-1,000-years-of-jewish-history">https://www.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/news/2013...

2/Oxbridge acquired the Lewis-Gibson fragments from Westminster College, a Presbyterian seminary (now United Reformed) whose land, and whose geniza fragments, they received as a donation from Agnes Lewis and Margaret Gibson (both b. 1843; they were twins).

3/Lewis and Gibson were extraordinary scholars who happened to have married wealthy men who died and left them fortunes, freeing them to pursue scholarship full time. That meant going to Egypt in search of manuscripts. @atlasobscura https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/how-lady-bible-hunters-made-the-victorian-eras-most-stunning-scriptural-find">https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/...

4/After a journey during which they bought fragments that turned out to be from the Cairo geniza, Lewis and Gibson brought this leaf back to Cambridge and showed it to Solomon Schechter, thus catalyzing the removal of the geniza’s contents to the UL. https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-OR-01102">https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-O...

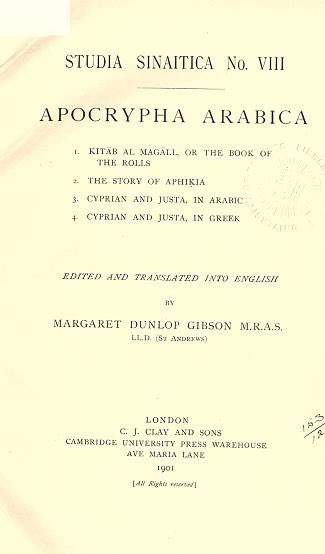

5/For a century, scholars referred to Lewis and Gibson somewhat condescendingly as “two Scottish ladies,” “the twins,” or “the Giblews.” In fact, they were formidable philologists with a dozen classical languages between them. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc2.ark:/13960/t1sf2v431">https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt... & https://archive.org/details/apocryphaarabica00gibsuoft">https://archive.org/details/a...

6/Admittedly, Lewis and Gibson were partly responsible for the trivializing tone in which their collecting was recounted. But while most 19th c travelogues sound mawkish to us now, the tales of males have mostly been modernized. https://books.google.com/books/about/Eastern_Pilgrims.html?id=B_AEAAAAYAAJ">https://books.google.com/books/abo... cf. https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.34051">https://doi.org/10.17863/...

7/Lewis and Gibson were also among the first to identify and read the palimpsested Greek Bible codices at the Monastery of St. Catherine in Sinai. There’s more on their work in this excellent article by @RJWJefferson: https://www.academia.edu/7042740/Sisters_of_Semitics_A_Fresh_Appreciation_of_the_Scholarship_of_Agnes_Smith_Lewis_and_Margaret_Dunlop_Gibson?source=swp_share">https://www.academia.edu/7042740/S...

8/But back to the eleventh century: this letter also had a multipart history of ownership and circulation during the Middle Ages.

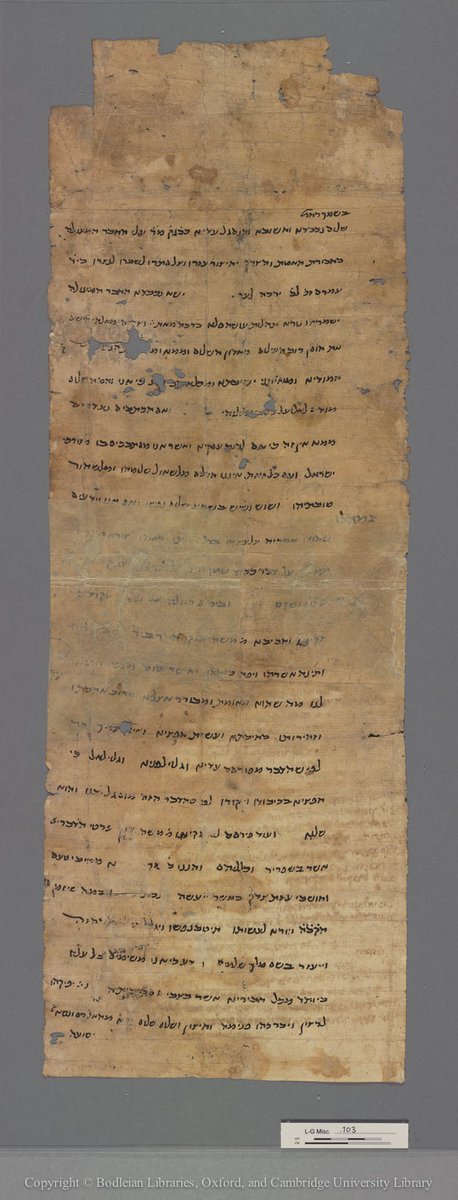

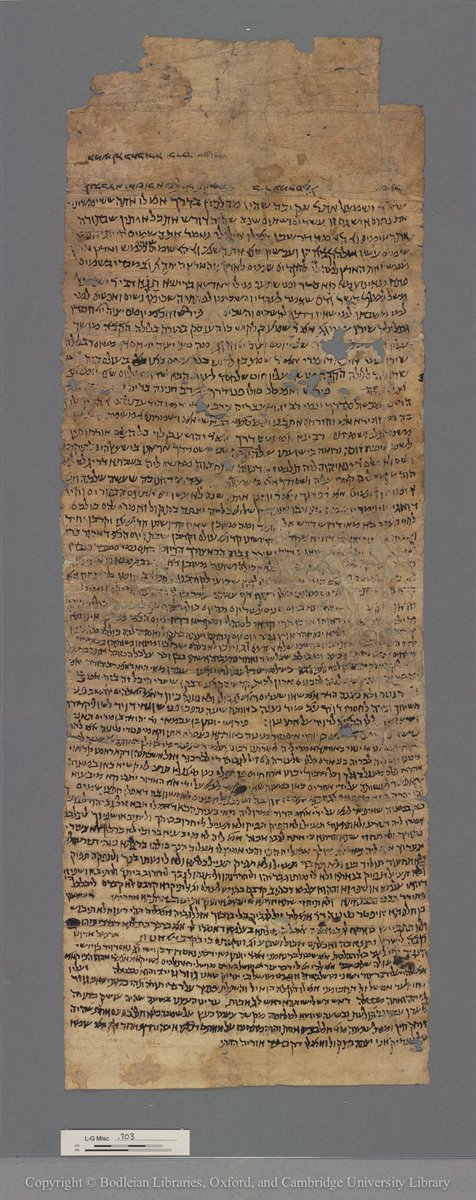

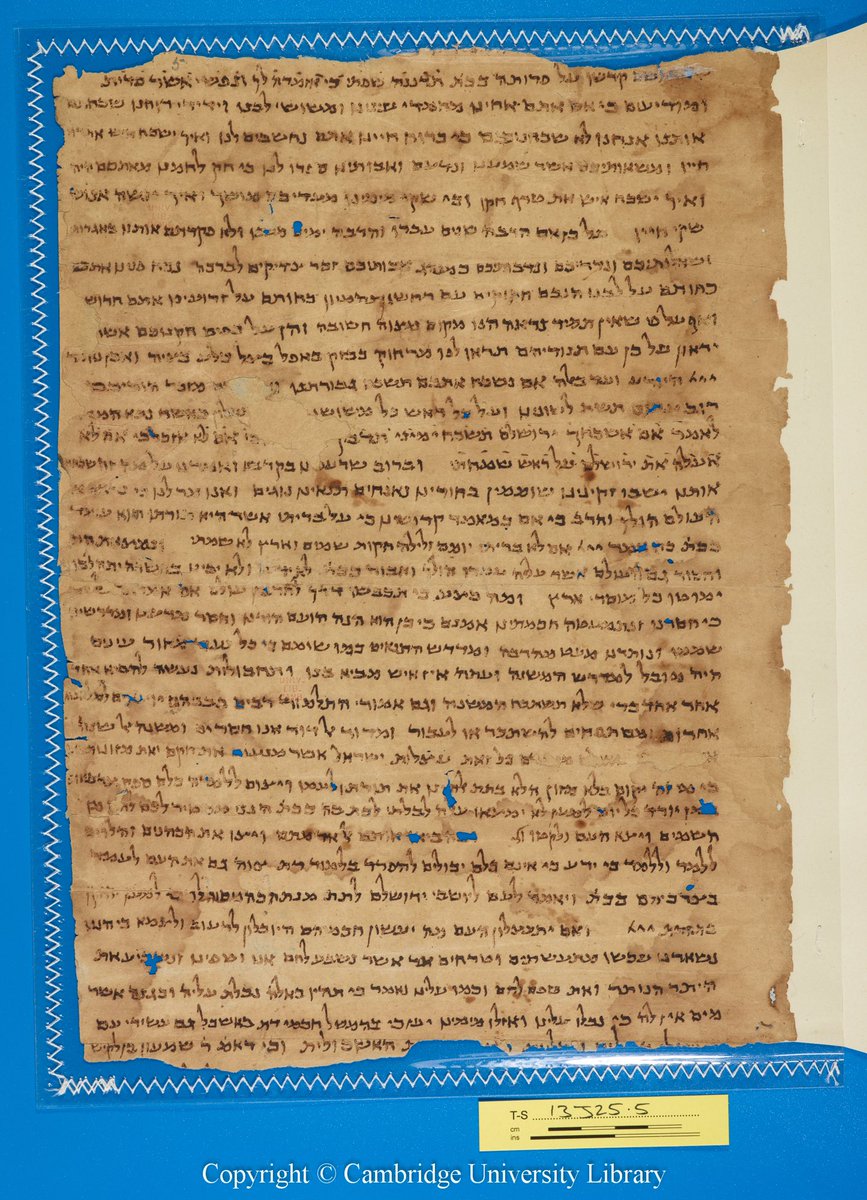

9/It’s a letter from Daniel b. ʿAzarya, ga’on (head) of the Jerusalem yeshiva from 1051 to 1062. The yeshiva was a high court and university rolled into one, and he became its leader even though, unlike his predecessors, he was not local but Iraqi. https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-MOSSERI-II-00141-00005">https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-M...

10/By 1038, both of Iraq’s yeshivot had closed, depriving Daniel b. ʿAzarya of an outlet for his ambition. So he headed west, to Qayrawān and then Jerusalem. His outsider origins may have helped him bypass the usual succession through the yeshiva’s ranks. https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-TS-00012-00058">https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-T...

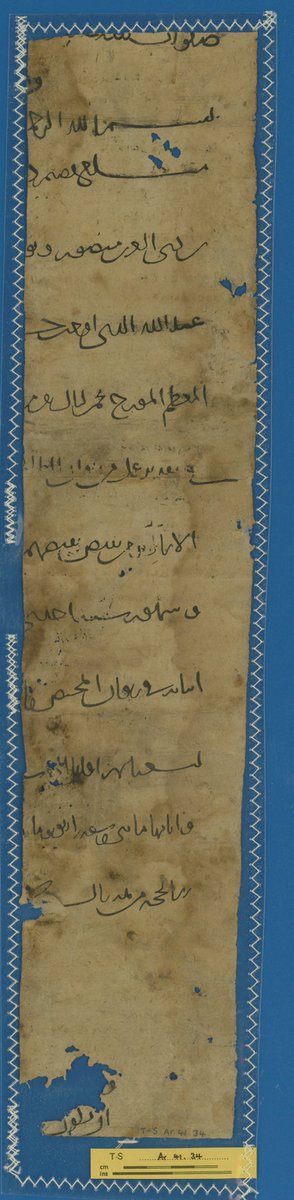

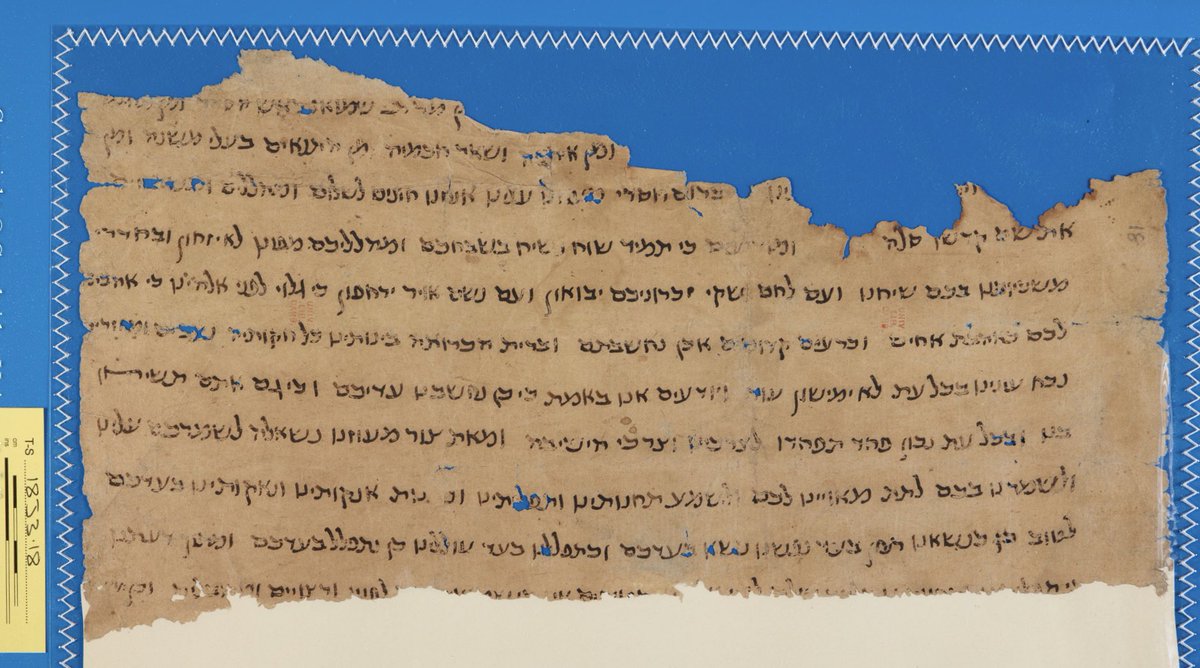

11/That same ambition and outsider status also predisposed him to displays of pretense and vanity. Note the wide line-spacing in the letter: his private and pastoral missives imitate the layout of Abbasid and Fatimid caliphal decrees.

12/Contemporaries would have been impressed by Daniel b. ʿAzarya’s layout. I see him as a man who used all the trappings of authority he could muster. (This letter is in the hand of a scribe, meaning he also ran his own yeshiva chancery. Wah-wah-wee-wah https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😯" title="Schweigendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Schweigendes Gesicht">) https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-LG-MISC-00103">https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-L...

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😯" title="Schweigendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Schweigendes Gesicht">) https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-LG-MISC-00103">https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-L...

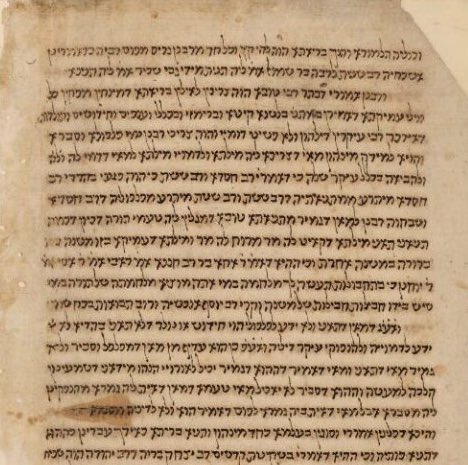

13/Some of the geonim of Baghdad had copied their letters w/wide line-spacing, too, including Neḥemya b. Kohen Ṣedeq (d. 968), Sherira b. Ḥananya (968–1004), Shemuʾel b. Ḥofni (d. 1013) and Hayya b. Sherira (1004–38). Here is one of Sherira’s. https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-TS-AS-00148-00049">https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-T...

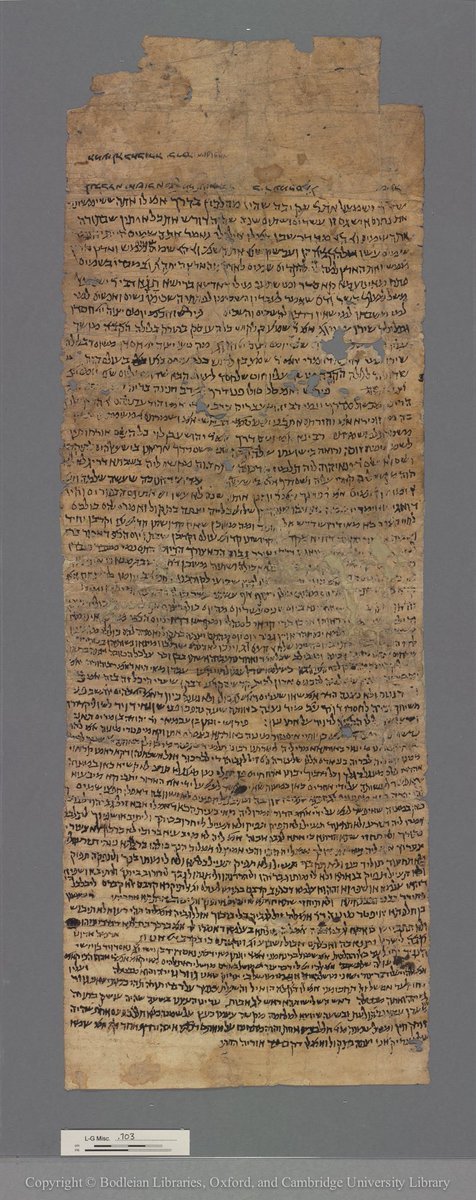

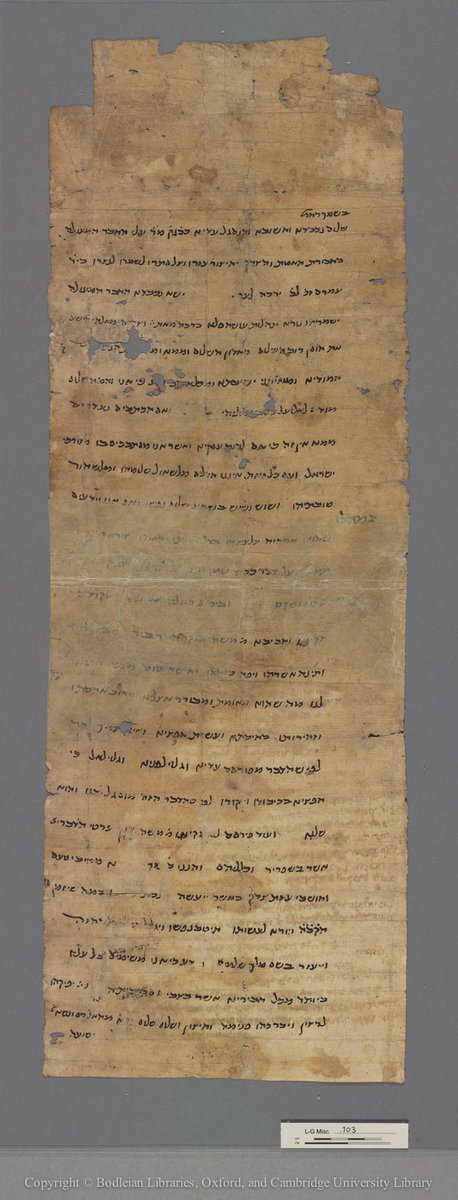

14/Now for the last bit, the reuse. Daniel b. ʿAzarya addressed his letter to ʿEli b. ʿAmram, a cantor in Fusṭāṭ. (The address is on verso, top, upside down.) Then ʿEli b. ʿAmram used the blank verso to copy out passages from the Babylonian Talmud. But not by chance.

15/The passages are from Ḥagiga and Moʿed Qaṭan, and they skip around. Why the melange? Like all medieval cantors, ʿEli b. ʿAmram had to compose new material all the time. Expediency dictated quoting, sometimes at length, often out of order. https://www.dropbox.com/s/pdvtra049pyv11p/Rustow_2020_Lost%20archive_Chs%2014%20and%2015.pdf?dl=0">https://www.dropbox.com/s/pdvtra0...

16/But his choice of format is significant: cantors often used rotuli to copy notes for oral performances, a continuation of the Hellenistic practice of distinguishing a hypomnema from an official text. (Oops! I quoted Foucault. @RachelSchine)

17/If you wanted a ready-made rotulus, reusing a fancily written letter or decree would save you time, money and glue.

18/Now a question. Some of you have heard of the Baghdadi geonim I mentioned above. But you may not have heard of Daniel b. ʿAzarya. Why? The answer would probably require a book, but here I’ll suggest a couple of factors: transmission and distance.

19/Transmission: to my knowledge, no one copied Daniel b. ʿAzarya’s works for posterity. They haven’t survived outside the geniza, and those inside are in his hand or his scribe’s. The works of the Iraqi ge’onim, in contrast, survived in multiple copies. https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-TS-00020-00152">https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-T...

20/Distance: the Iraqi ge’onim sent their works to places like Qayrawān and Córdoba, and on the way, they passed through Cairo, where their contacts copied the texts. The more distance their works covered, the more copies proliferated.

21/The more copies of a work, then, the better the chance of its survival. Sometimes survival or failure to survive is a matter of contingency, not a measure of literary worth.

22/Which leads me to this: The *decline* of the Iraqi geonim may explain their “stickiness,” their long posterity in Jewish literature. They sent works westward in exchange for donations; they asked for donations when the yeshivot were in crisis. https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-TS-00013-J-00025-00005">https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-T...

23/Had Daniel b. ʿAzarya lived a generation earlier, perhaps his works would have met the same happy fate: survival not by chance but by design. Works copied in many places often survive better. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cod._Hebr._120_-_Zalman_Stern_1849_---_12a.jpg">https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter