Should we do PCI in patients with stable coronary artery disease?

Young Guillaume Marquis-Gravel took on this topic at a recent meeting of #CVCTForum. He brought together a wide range of research expertise: DJ Moliterno, P Jüni, YD Rosenberg, BE Claessen, RJ Mentz, R Mehran, DE Cutlip, C Chauhan, S Quella, SG Goodman and Faiez Zannad

He somehow melded together all these diverse opinions, and even got a little contribution from me, to produce a very helpful summary of where we are in research, and WHY it is so difficult to answer the questions we really are curious about. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0735109720355248">https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/a...

Because it is brutally paywalled, I thought I might take you through some of his argument?

In short, we all THINK we know what question we want answered, but do we? And are we willing to do the research we need to do, to get that answer reliably?

In short, we all THINK we know what question we want answered, but do we? And are we willing to do the research we need to do, to get that answer reliably?

I thought I would have to upgrade its aggressiveness, but he had already built this into his brilliant opening paragraph. "OK you can say that Guillaume, but make sure everyone knows it was not me who contributed that particular snippet!"

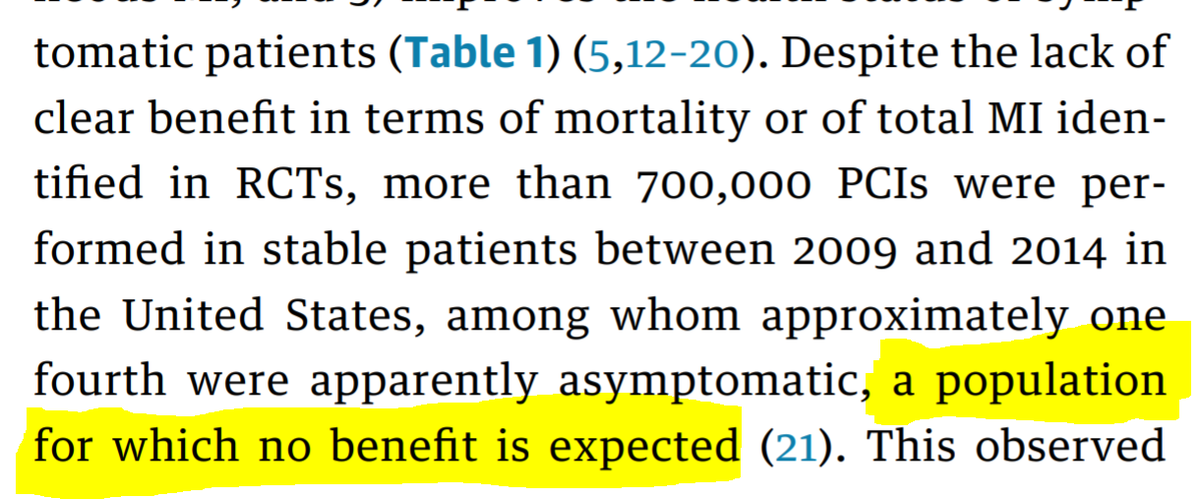

Then a nice summary of the nub of the problem. Everyone (including me, the biggest sceptic) believes that PCI in stable CAD is good for you. So we do it.

We just don& #39;t know how to demonstrate it to the level that we believe.

We just don& #39;t know how to demonstrate it to the level that we believe.

First of all, however widely you *plan* to throw the net, exclusion criteria and hesitancies creep in bit by bit, and you end up with a far smaller than the "all-comers" you were hoping for.

I think there is no way round it. You can& #39;t, in fact, study all-comers. Because not all comers agree to be randomized. And not everyone having an intervention clinically is part of the classical group having the intervention that we consider (when just chatting) to be "typical"

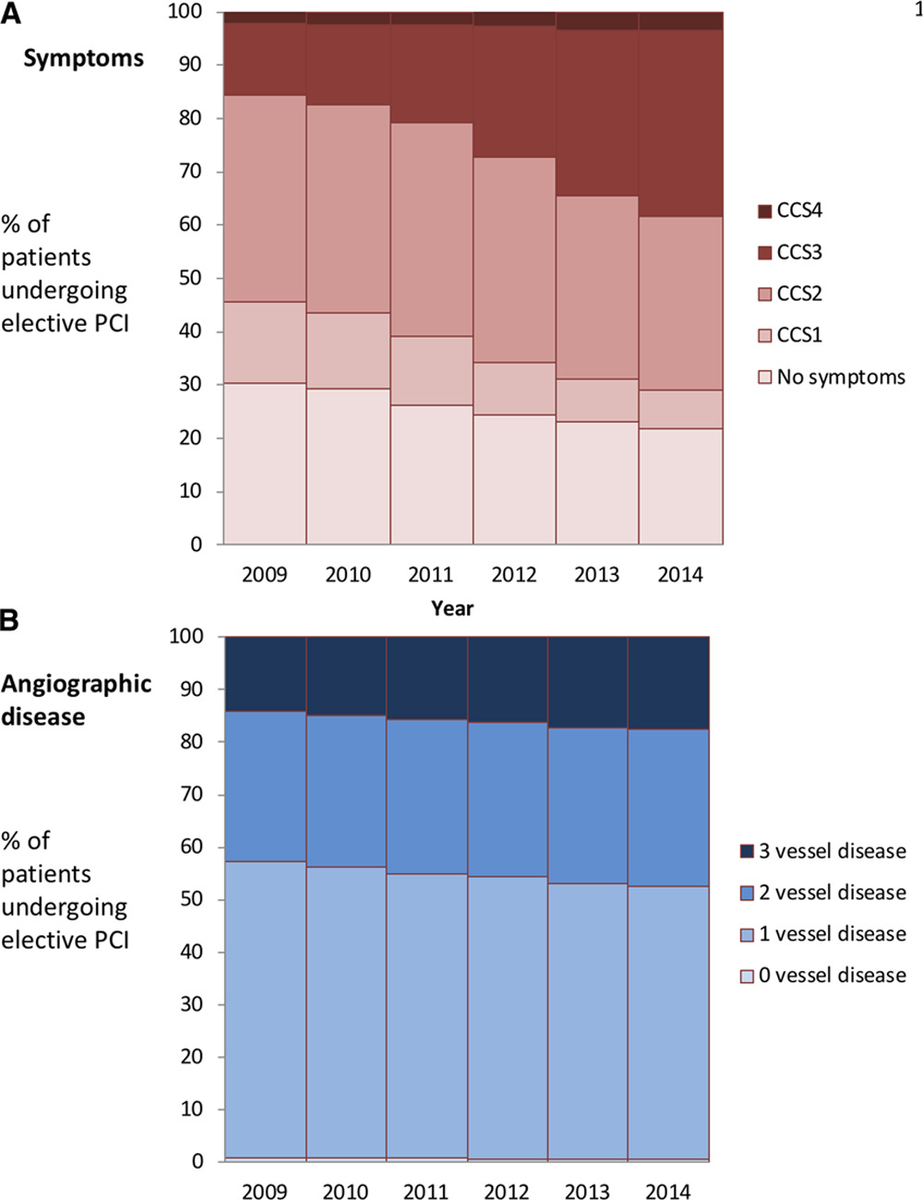

For example, until @rallamee ran ORBITA, I had assumed that almost all stable PCI was done for angina. I had no idea of the number of people that ended up on the clinical PCI

table for all kinds of reasons.

table for all kinds of reasons.

Had a CXR, done for some random indication, which revealed some coronary calcification? Subsequent angiogram shows tight lesion?

What will the patient want?

What will the patient want?

Breathless and had an exercise test? ST depression?

Angiogram shows a tight lesion?

What will the patient want?

Angiogram shows a tight lesion?

What will the patient want?

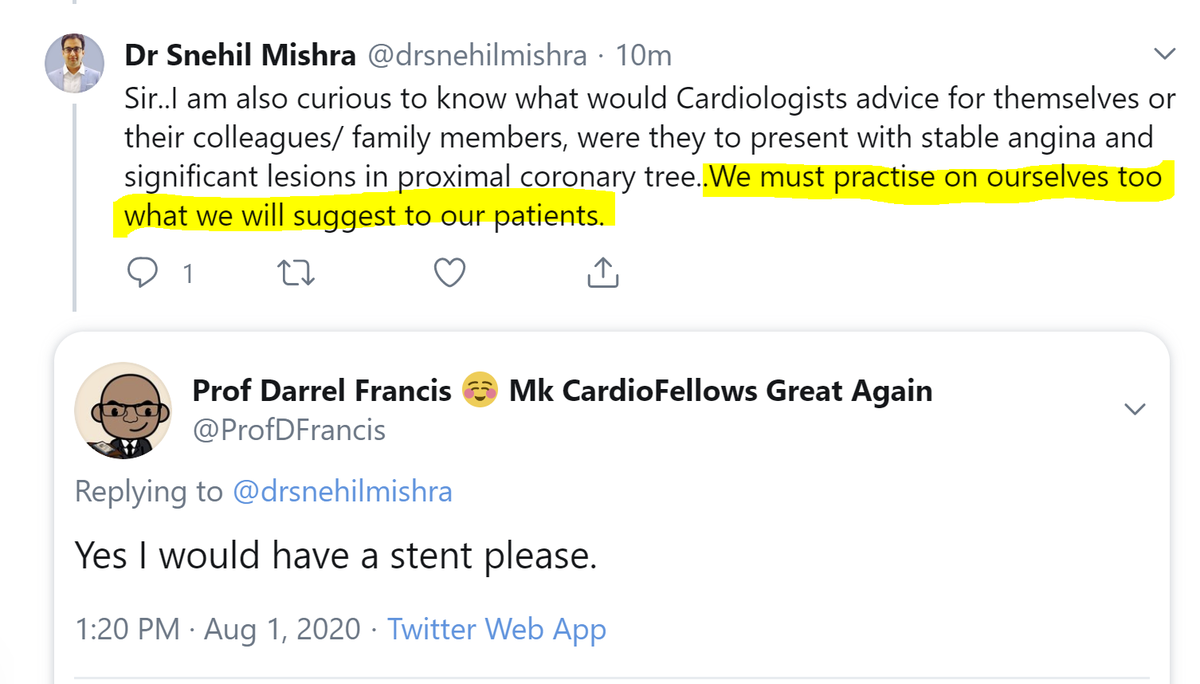

However, I actually am going to pull you up on this concept here. It is commonly stated, but let& #39;s think about it.

Should we advice patients to make the choices we ourselves would make?

If a (current) drug addict gives a lecture to young people in a school, not to get addicted to drugs, is that:

Does the fact that the speaker is not obeying the advice, make the advice incorrect?

Why is the speaker not following his or her own advice?

Yes. If I say the earth is ~93 million miles from the sun, whether that is true or not is unrelated to who I am or what I do.

Likewise advice to stop smoking is equally VALID from a smoker as for a non-smoker.

Likewise advice to stop smoking is equally VALID from a smoker as for a non-smoker.

It is just less likely to be PERSUASIVE.

I would argue that as interventional cardiologists trained in a previous era, it is too late for us.

I would argue that as interventional cardiologists trained in a previous era, it is too late for us.

We have put so many stents into people with stable CAD based on the belief that they are good for you, that it is impossible for us to even imagine the possibility that they are prognostically neutral or worse.

"An important scientific innovation rarely makes its way by gradually winning over and converting its opponents: it rarely happens that Saul becomes Paul.

What does happen is that its opponents gradually die out, and that the growing generation is familiarized with the ideas from the beginning: another instance of the fact that the future lies with the youth."

Max Planck, Scientific autobiography, 1950, p. 33, 97

Max Planck, Scientific autobiography, 1950, p. 33, 97

My argument is that it is too late for us oldies in cardiology. We have been brought up to think of PCI for stable ischaemic heart disease as de rigeur.

We have long thought that research to *test* it is merely an academic obsession of no practical merit.

We have long thought that research to *test* it is merely an academic obsession of no practical merit.

So now that we come to try to imagine it, we HAVE to blank out from our minds all previous patients we have stented for stable IHD, especially the asymptomatic ones (who have been 20-30% of them in the past).

USA figures from NCDR:

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.118.005025">https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.11...

USA figures from NCDR:

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.118.005025">https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.11...

"Hypocrisy does not imply invalidity."

S Burns and D Francis

Annals of Excuses for KoLs, 2020

S Burns and D Francis

Annals of Excuses for KoLs, 2020

It is too late for us to think in an evidence-based way about PCI. Lesion? We want a stent, that& #39;s it.

So to put us in the right frame of mind, let& #39;s ask ourselves this. (Vascular surgeons please do not answer.)

Suppose you develop leg-gina. What would you want to have first?

So to put us in the right frame of mind, let& #39;s ask ourselves this. (Vascular surgeons please do not answer.)

Suppose you develop leg-gina. What would you want to have first?

Yes I& #39;ve forgotten the name of it. I can afford to at my age. What is it really called? Angina Legoris, or something?

And how about elbo-gina? Pain when you throw darts in a pub.

And how about elbo-gina? Pain when you throw darts in a pub.

It& #39;s easy!

Unless it happens to be an-gina, at which point we blow our top and start scurrying about like terrified rabbits.

Unless it happens to be an-gina, at which point we blow our top and start scurrying about like terrified rabbits.

We see people dying of coronary disease.

We know a stent is simple and safe.

EVERYONE we know professionally thinks the same as us.

So even our "lay network" pushes us to PCI.

We know a stent is simple and safe.

EVERYONE we know professionally thinks the same as us.

So even our "lay network" pushes us to PCI.

So for experienced interventionists to randomize, we need to be ready to feel uncomfortable and indeed hypocritical.

Some people can& #39;t do that. But that would be like a drug addict being unwilling to warn off children from taking up the bad habit.

Some people can& #39;t do that. But that would be like a drug addict being unwilling to warn off children from taking up the bad habit.

And the situation for us is even worse. Who puts the idea into the patient& #39;s head that an-gina is in need of procedural intervention, but leg-gina and elbo-gina, is not?

If you voted for "Their friends" or "The Media", where do you propose they, in turn, got hold of the idea?

Before we started doing it, and telling people that it was a good idea, not a single relative or newspaperman pushed patients to have PCI.

So it is actually us, indirectly

Before we started doing it, and telling people that it was a good idea, not a single relative or newspaperman pushed patients to have PCI.

So it is actually us, indirectly

Guillaume also put an end to any talk of "crossover" after completion of ORBITA. In ORBITA, patients were _delaying_ clinically indicated PCI, for a limited period, _purely_ to help future patients with angina.

Their participation in ORBITA was in no way for their own benefit.

What they did after they completed the trial and exited, which is in most cases have PCI if not received during the trial, is exactly what we were expecting and recommending.

What they did after they completed the trial and exited, which is in most cases have PCI if not received during the trial, is exactly what we were expecting and recommending.

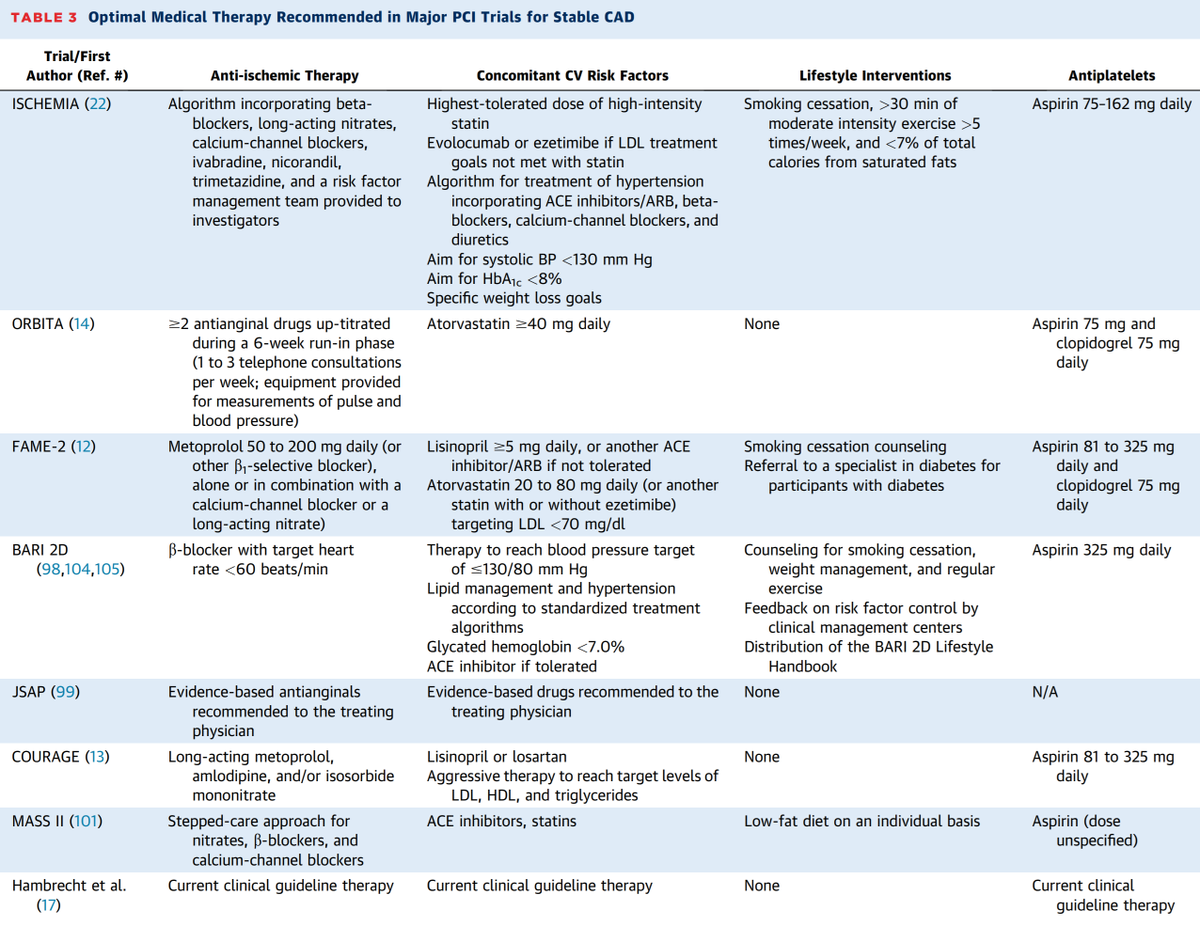

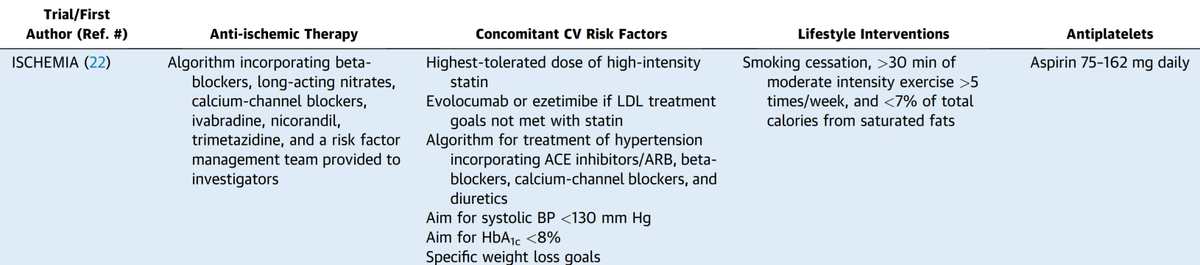

Guillaume also got rid of the feeble-minded term "medical therapy", which is embarrassingly vague for a specialty that considers itself unusually scientific amongst doctors.

"Medical therapy" is an amorphous gloop.

"Medical therapy" is an amorphous gloop.

When anyone talks about "medical therapy", slap him and say that you were merely responding. When he looks surprised, ask "Oh, so you think a slap in the face is different from a verbal response?"

This will instantly make him understand that he should be more precise.

This will instantly make him understand that he should be more precise.

Or it may not. But it is good fun.

So called "medical therapy" is divided into two things.

* Things to stop you having heart attack or dying.

* Things to stop you having angina.

These are completely different and unrelated aims. In fact he breaks down trial meds in even more detail.

* Things to stop you having heart attack or dying.

* Things to stop you having angina.

These are completely different and unrelated aims. In fact he breaks down trial meds in even more detail.

Regarding endpoints, the article makes special effort to avoid sloppy terminology such as "soft" and "hard". I consider these to be imbecilic when we have much better terminology.

(1) Does the endpoint matter to patients?

(2) Is its evaluation unbiased?

(1) Does the endpoint matter to patients?

(2) Is its evaluation unbiased?

The key question of bias is nothing to do with honesty or dishonesty of investigators. Even the most honest investigator biases themselves and the patient.

The classic proof of this is from DEFER and FAME 2.

The classic proof of this is from DEFER and FAME 2.

In both trials, there was a group of people who had their angina severity (CCS class) rated before and after being told their lesion was not haemodynamically significant.

This was how much that psychological intervention affected the result.

Much bigger than the PCI effect!

This was how much that psychological intervention affected the result.

Much bigger than the PCI effect!

This is the interesting question, isn& #39;t it?

We want to prevent death, but that is really hard to do.

The event-prevention half of medical therapy is really effective. And ISCHEMIA was absolutely splendid at it!

We want to prevent death, but that is really hard to do.

The event-prevention half of medical therapy is really effective. And ISCHEMIA was absolutely splendid at it!

We think we want to "prevent MI", but this is not straightforward.

Some MI& #39;s are disruptive to the patient& #39;s life, making them go in to hospital. Others are not, in the sense that we pick them up incidentally, such as discovering raised troponin after elective PCI.

Some MI& #39;s are disruptive to the patient& #39;s life, making them go in to hospital. Others are not, in the sense that we pick them up incidentally, such as discovering raised troponin after elective PCI.

Are they equivalent 1:1?

i.e. Is an option that prevents one of one category and adds one of the other category, perfectly neutral?

i.e. Is an option that prevents one of one category and adds one of the other category, perfectly neutral?

Obviously, as an interventionist, I am tempted to do the sums in the way that favours my specialty.

i.e.

"let& #39;s make a big distinction between the MI& #39;s that bring you into hospital, and those that are documented incidentally"

But I already know which way this tilts the scales.

i.e.

"let& #39;s make a big distinction between the MI& #39;s that bring you into hospital, and those that are documented incidentally"

But I already know which way this tilts the scales.

Meanwhile, when we compare PCI with CABG, we want to "fly the flag" for PCI, and we know CABG causes more troponin elevations than PCI, so it is tempting to - in that case - say "periproc MI must be counted!"

But again, we know in advance which way this tilts the scales.

But again, we know in advance which way this tilts the scales.

What is the right way to do the arithmetic?

It needs a choice. How to prevent bias?

It needs a choice. How to prevent bias?

Blinded endpoint committees are commonly build into trials. They look at the clinical data around each event, and decide whether each event is valid or not, without knowing which arm the patient is in.

The idea is to prevent bias.

The idea is to prevent bias.

However, how do they solve the conundrum of deciding whether to count periproc MI or not?

And prespecification of endpoints is designed to stop us changing the endpoint definition AFTERWARDS, to favour our desired hypothesis.

However, how does that help when we are CHOOSING the endpoint DURING DESIGN of the trial, when we know the effect of our choice?

However, how does that help when we are CHOOSING the endpoint DURING DESIGN of the trial, when we know the effect of our choice?

As you have correctly deduced, neither of the options contribute ANYTHING to the problem of deciding IN ADVANCE what to count.

Which is why these early answers are so disappointing.

Which is why these early answers are so disappointing.

First 7 people were all wrong!

Because we see nice-sounding things like "blinded" and "pre-specify" and we assume they fix everything.

But they don& #39;t, and we don& #39;t think enough about it.

Because we see nice-sounding things like "blinded" and "pre-specify" and we assume they fix everything.

But they don& #39;t, and we don& #39;t think enough about it.

Consider this proposition:

"If we only measure reduction in CHEST PAIN, we will underestimate the benefit of PCI on symptoms."

"If we only measure reduction in CHEST PAIN, we will underestimate the benefit of PCI on symptoms."

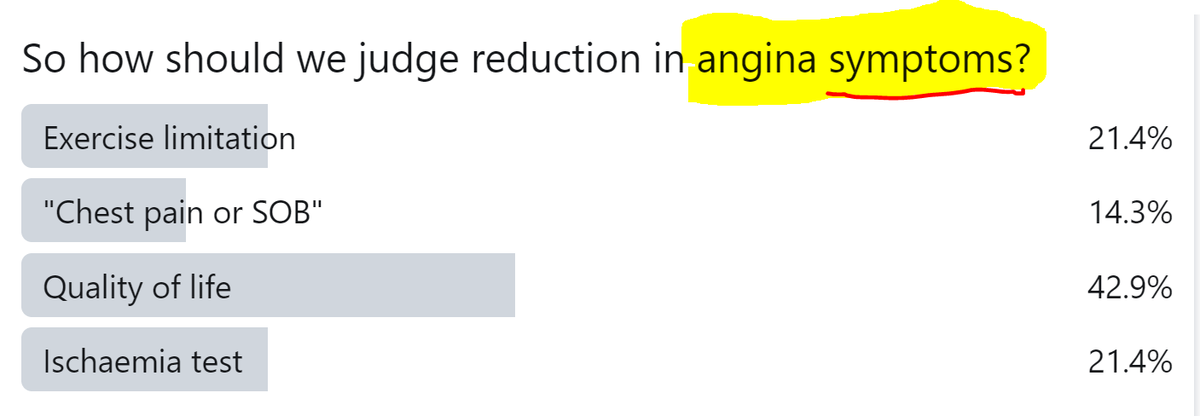

So how should we judge reduction in angina symptoms?

Each of the options could be advocated.

An exercise test nicely captures the limitation, regardless of whether it is experienced as chest pain or as shortness of breath.

HOWEVER, it also captures the limitation if it is non-cardiac.

An exercise test nicely captures the limitation, regardless of whether it is experienced as chest pain or as shortness of breath.

HOWEVER, it also captures the limitation if it is non-cardiac.

Broadening from "Chest Pain" to "Chest Pain or SOB" is good if the patient has what is euphemistically called "Angina equivalent"

HOWEVER, what is the difference between that an somebody who is a bit chubby and has asymptomatic ischaemia?

HOWEVER, what is the difference between that an somebody who is a bit chubby and has asymptomatic ischaemia?

Quality of life sounds like a good thing to aim for.

But there are many influences on it, of which angina symptoms may be a small minority. So even a useful effect on angina (whatever that may be) may be drowned out by irrelevant noise.

But there are many influences on it, of which angina symptoms may be a small minority. So even a useful effect on angina (whatever that may be) may be drowned out by irrelevant noise.

And finally, I thought nobody would go for this, but there are still some die-hards, that would measure SYMPTOMS with a test that is nothing to do with symptoms!

When we THINK we are listening to the patient& #39;s symptoms (7), we are in fact getting powerful pointers from:

Anatomy (1)

Physiology (2)

Ischaemia imaging (3)

Anatomy (1)

Physiology (2)

Ischaemia imaging (3)

And when the patient comes back after the PCI, with the same somewhat-chestpainy-somewhat-breathlessy indeterminate symptom, we automatically do the clinical correct thing, which is:

Show them the wide open artery ("look at it, it& #39;s like a 10-lane motorway!"),

the normal physiology ("wow, what a surge of blood flow!")

and the normal ischaemia imaging ("see how wonderfully the heart is getting blood supply on this scan!")

the normal physiology ("wow, what a surge of blood flow!")

and the normal ischaemia imaging ("see how wonderfully the heart is getting blood supply on this scan!")

When we write our clinical records, we THINK we are getting the history, raw and honest, from the patient, but we ourselves (and the patient, once we tell them) are inevitably biased by all the wonderful reassuring news we have.

We may have done no more than reclassify a dubious symptom

from "Definite angina" when we knew they had a full house of anatomy, invasive physiology and ischaemia imaging,

to "Atypical twinges" when we know they had a full house of all-clear& #39;s.

from "Definite angina" when we knew they had a full house of anatomy, invasive physiology and ischaemia imaging,

to "Atypical twinges" when we know they had a full house of all-clear& #39;s.

Incidentally, @AlexNowbar, @chrisrajkumar and @rallamee have set up a series of experiments to study this issue of how to interpret symptoms of intermediate convincingness, and I look forward to see what emerges over the next few years.

In ORBITA-2 they have built an approach of asking patients to pre-specify their own individual angina, and then only randomizing if the patient manages to re-suffer the same symptom, in the couple of weeks before the planned randomization.

And the patients report symptoms daily.

And the patients report symptoms daily.

There is so much more in Guillaume& #39;s tour-de-force.

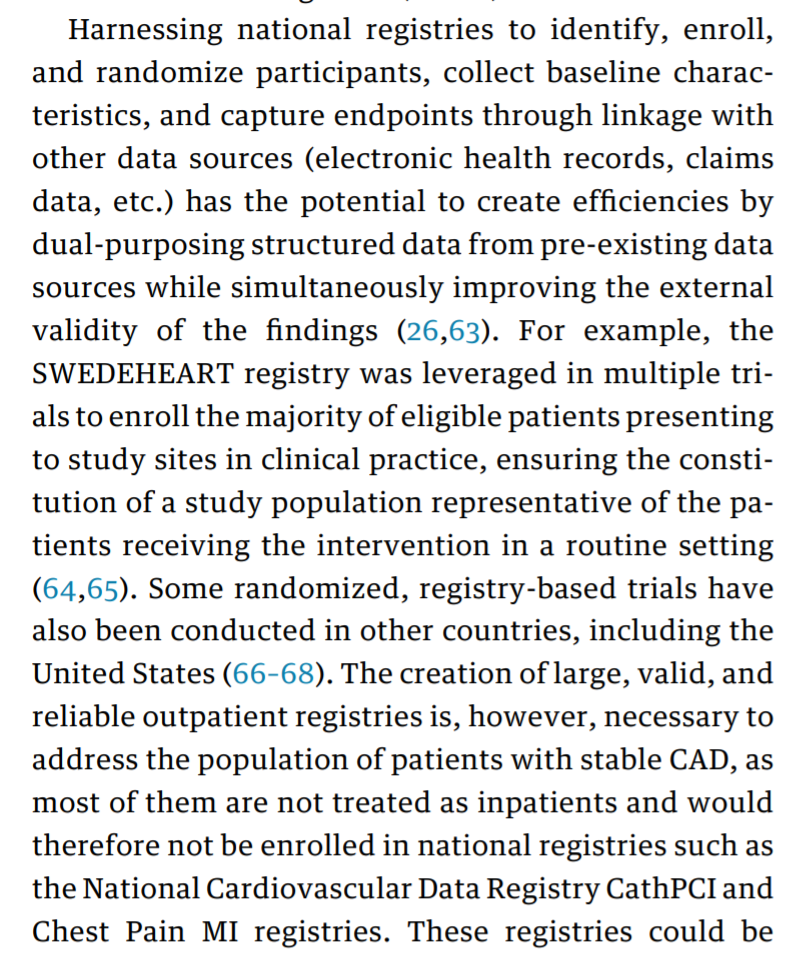

How to cut back on the vast cost of clinical trials?

How to cut back on the vast cost of clinical trials?

And this amazing anecdote. Did you know how it was first discovered that Internal Mammary Artery LIGATION (not grafting) was, in reality, rubbish?

Not by thinking about it abstractly - lots of plausible mechanisms.

Not from clinical experience - that was universally favourable.

Not by thinking about it abstractly - lots of plausible mechanisms.

Not from clinical experience - that was universally favourable.

Let me not take up too much of your weekend.

I personally learned a lot from helping with the paper. For example, I had no idea that Transmyocardial Laser Revasc had made it into guidelines before it was ultimately debagged!

I personally learned a lot from helping with the paper. For example, I had no idea that Transmyocardial Laser Revasc had made it into guidelines before it was ultimately debagged!

And from whom is this a quote, do you think?

Which renegade skeptic or perpetual troublemakers? Wow!

Well - it must be easier to say for therapies that are not our bread and butter.

8-)

Have a good weekend!

Which renegade skeptic or perpetual troublemakers? Wow!

Well - it must be easier to say for therapies that are not our bread and butter.

8-)

Have a good weekend!

Do read the the paper, which has so much more good stuff. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0735109720355248">https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/a...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter