It is time to tell a very difficult story.

A story that happened exactly 101 years ago today.

This is the story behind an image that has been called the world& #39;s first photograph of a murder caught on film. I wish it was not relevant today. But it is. So here is a thread:

A story that happened exactly 101 years ago today.

This is the story behind an image that has been called the world& #39;s first photograph of a murder caught on film. I wish it was not relevant today. But it is. So here is a thread:

After the Civil War ended slavery, white supremacy soon found ways to re-establish itself in the South.

Sharecropping. Poll taxes. The KKK. Jim Crow laws.

Many Black Americans decided to leave the South. They flowed northward as part of a process we know as The Great Migration.

Sharecropping. Poll taxes. The KKK. Jim Crow laws.

Many Black Americans decided to leave the South. They flowed northward as part of a process we know as The Great Migration.

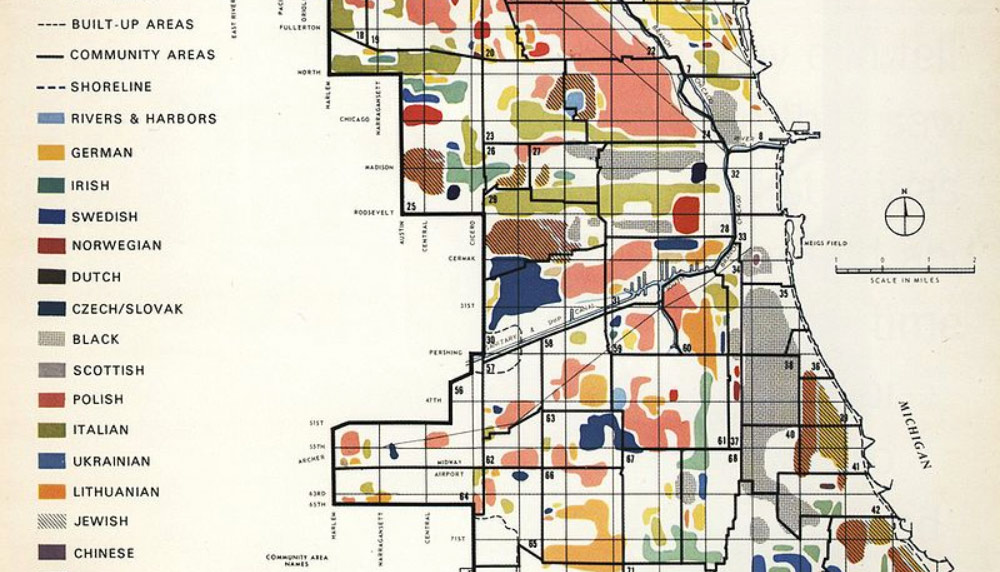

As northern cities beckoned African Americans with the promise of new industrial jobs and a better life, thousands came to places like Chicago.

They created vibrant neighborhoods like the Black Belt on Chicago& #39;s South Side. Chicago has been called the most segregated US city.

They created vibrant neighborhoods like the Black Belt on Chicago& #39;s South Side. Chicago has been called the most segregated US city.

With the end of World War I, many whites returning home found cities like Chicago were more diverse than what they remembered. And they were.

Black-white tensions boiled over as part of the "Red Summer." Chicago was a racial tinderbox.

Black-white tensions boiled over as part of the "Red Summer." Chicago was a racial tinderbox.

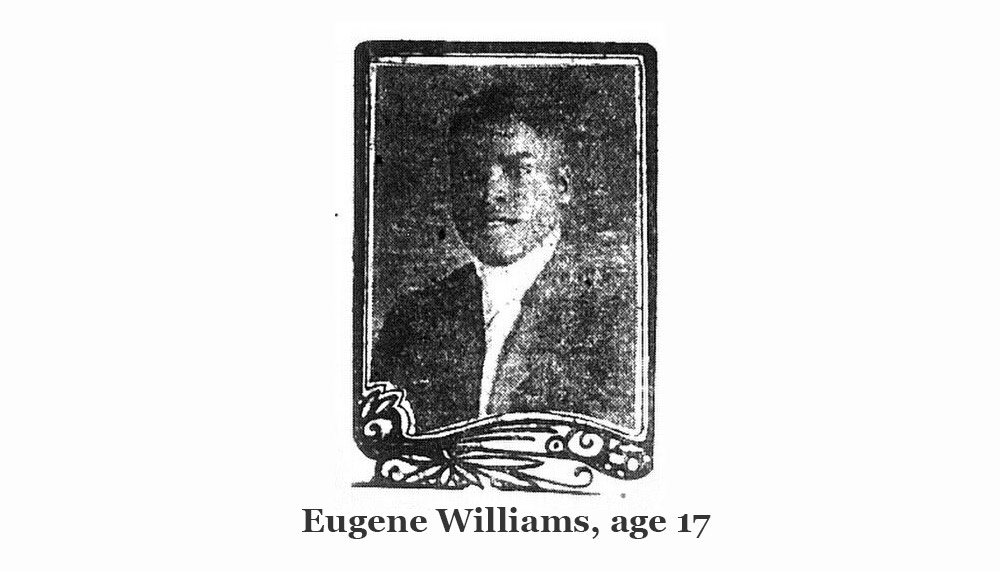

July 27, 1919. A 17 year old Black boy named Eugene Williams plays in the water at a public beach. He floats past an invisible color line.

A white man throws rocks at the boy. The stones keep coming, preventing him from returning to shore to flee. Williams drowns.

A white man throws rocks at the boy. The stones keep coming, preventing him from returning to shore to flee. Williams drowns.

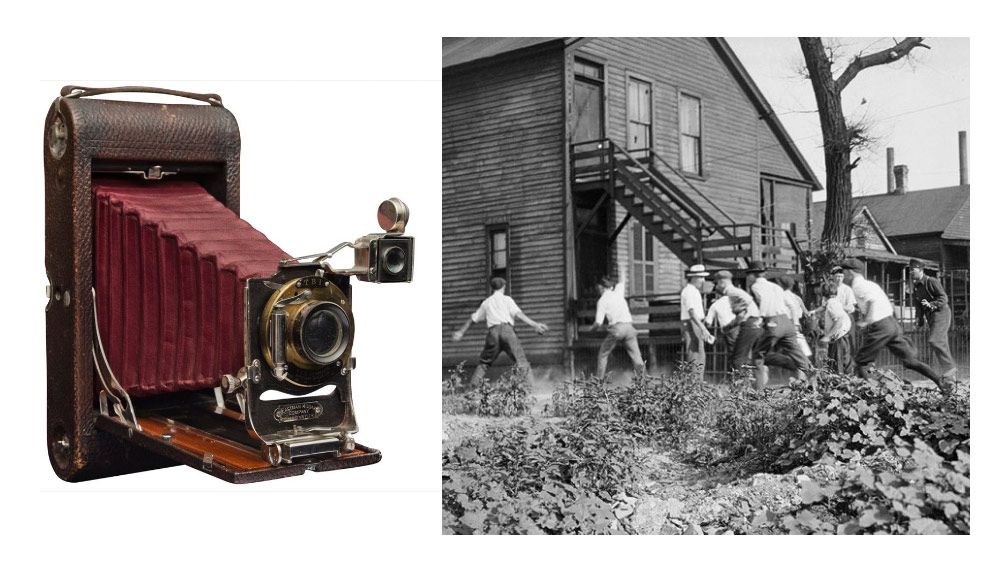

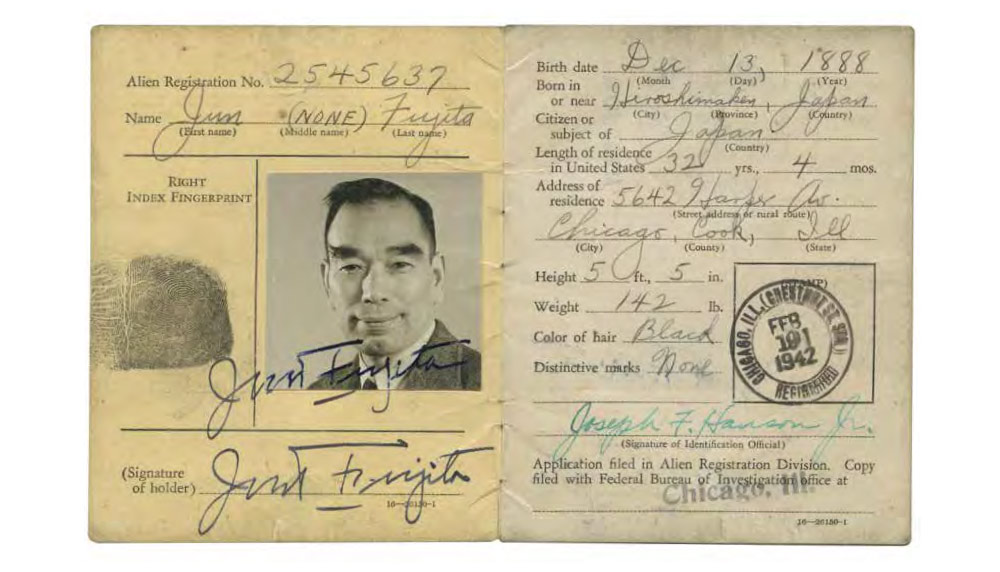

Cameras were not common during Chicago& #39;s 1919 race riot.

But remarkably we do have 1 picture of the angry crowd gathered at 29th St Beach after Eugene Williams was killed.

Taken by a 31 year old Japanese immigrant named Jun Fujita. Remember that name, because it& #39;s important.

But remarkably we do have 1 picture of the angry crowd gathered at 29th St Beach after Eugene Williams was killed.

Taken by a 31 year old Japanese immigrant named Jun Fujita. Remember that name, because it& #39;s important.

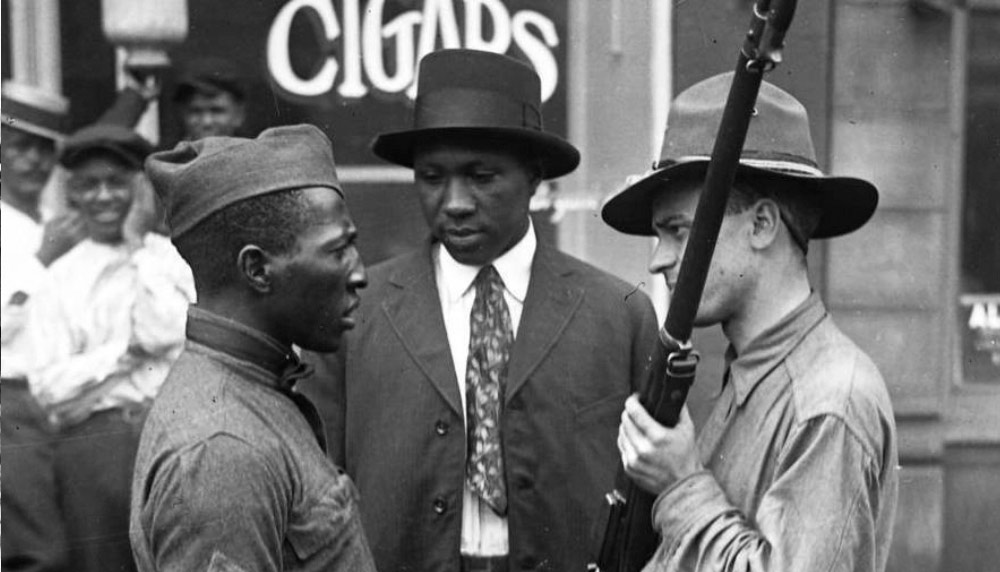

After Eugene Williams was murdered by a white man in 1919, a white Chicago police officer arrived.

The crowd easily identified the man who threw the stones that killed him the 17 year old Black boy.

But instead of arresting him, the white police officer arrests... a Black man.

The crowd easily identified the man who threw the stones that killed him the 17 year old Black boy.

But instead of arresting him, the white police officer arrests... a Black man.

After Chicago Police decided not to do their job of arresting the man who murdered Eugene Williams the city exploded in racial violence between angry Black & white mobs.

This is a photo of gleeful white children after they ransacked the home of a Black family. Racist looting.

This is a photo of gleeful white children after they ransacked the home of a Black family. Racist looting.

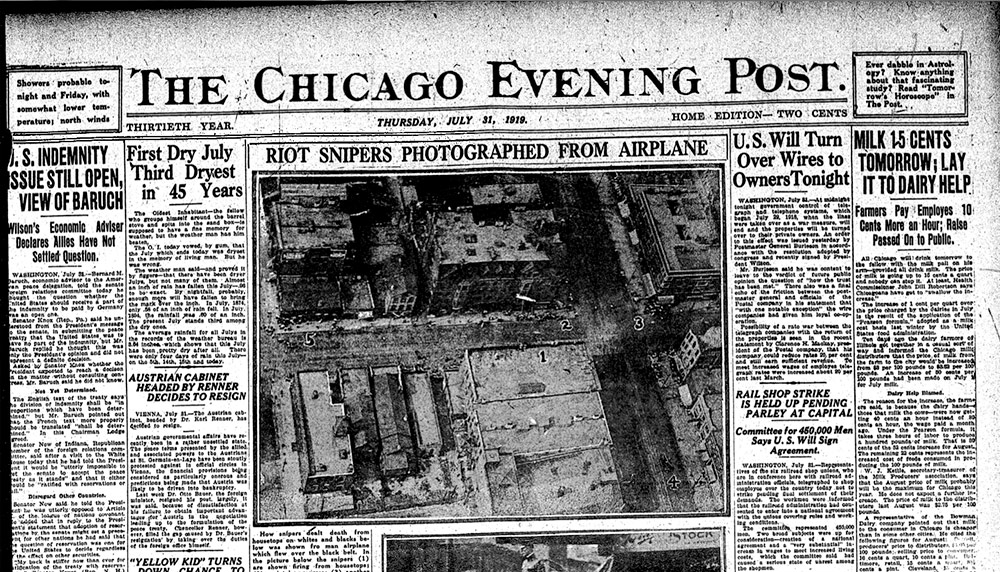

As Chicago& #39;s 1919 race riot unfolded rapidly, newspapers struggled to keep up with events.

Whites in Chicago didn& #39;t trust Blacks. And Blacks didn& #39;t trust whites.

But one newspaper– the Chicago Evening Post – has a secret weapon to help them cover the story.

Whites in Chicago didn& #39;t trust Blacks. And Blacks didn& #39;t trust whites.

But one newspaper– the Chicago Evening Post – has a secret weapon to help them cover the story.

Jun Fujita was a young immigrant photojournalist from Japan.

He was neither Black, nor white. He found ways to slip into all kinds of crowds–and he used that ability to great professional advantage.

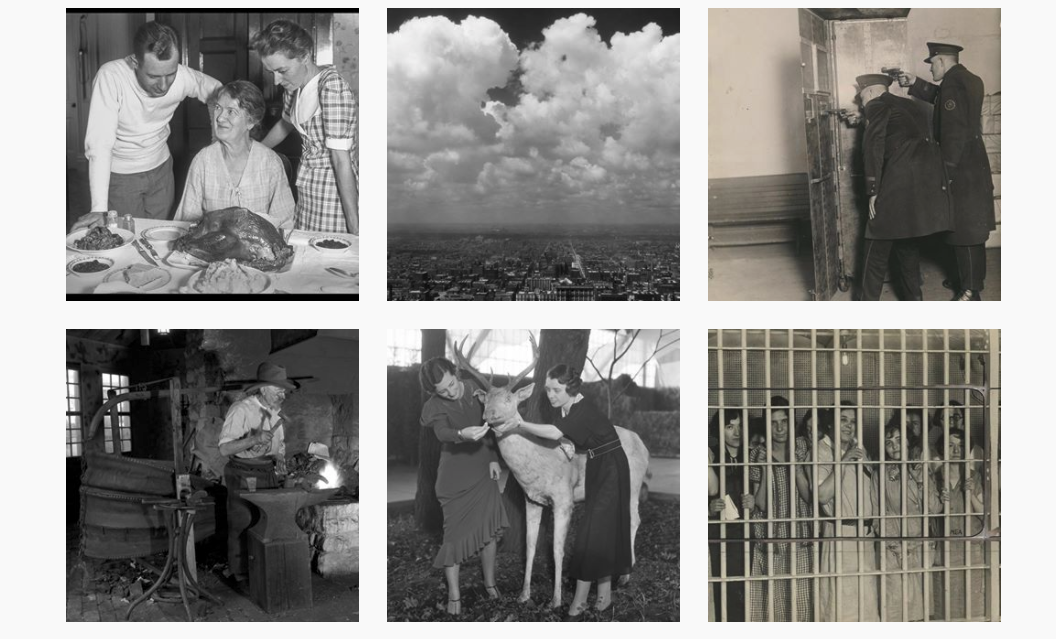

Many of the most iconic photographs in Chicago history were taken by Fujita.

He was neither Black, nor white. He found ways to slip into all kinds of crowds–and he used that ability to great professional advantage.

Many of the most iconic photographs in Chicago history were taken by Fujita.

Fujita the Japanese immigrant photographer was sent to cover Chicago& #39;s 1919 race riot by the paper he worked for.

He went to dangerous areas where fights were happening, close up. He even took aerial pictures of vigilante rooftop snipers from an early airplane.

He went to dangerous areas where fights were happening, close up. He even took aerial pictures of vigilante rooftop snipers from an early airplane.

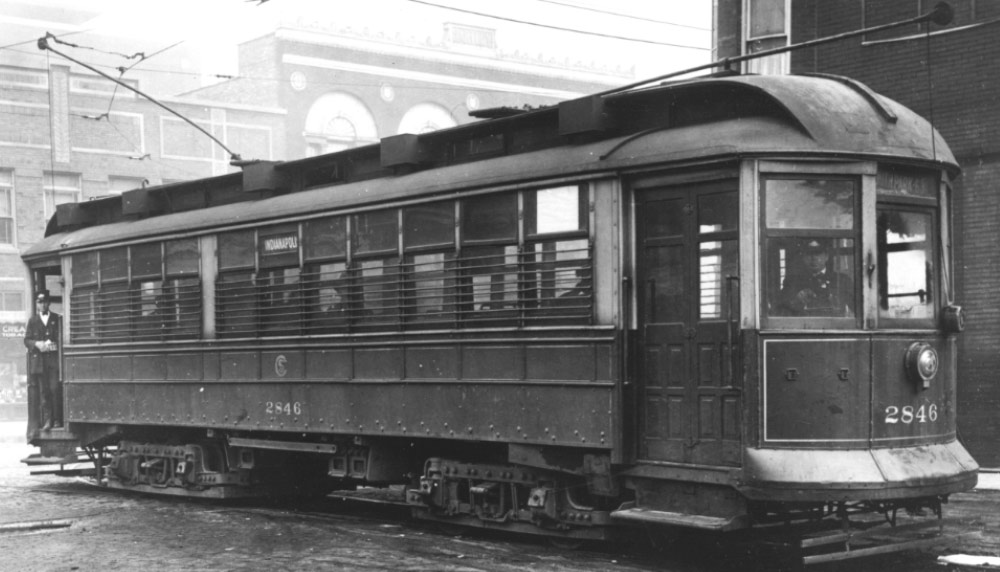

When the stockyards let out a shift of workers on July 28, 1919, a 30 yr old Black man named John Mills boarded a streetcar headed home.

But first the streetcar would need to travel through the white Irish neighborhood of Canaryville.

John Mills would never make it home.

But first the streetcar would need to travel through the white Irish neighborhood of Canaryville.

John Mills would never make it home.

Before we go any further with this story, I need to warn you: Yes, in a few tweets from now, I will be posting the photograph of the murder itself. The first murder caught on film.

It is a historically important image. And we can& #39;t really do the story justice without posting it.

It is a historically important image. And we can& #39;t really do the story justice without posting it.

As the 47th Streetcar carrying Mr Mills travelled through Chicago& #39;s Canaryville neighborhood it paused.

There was a white crowd of 300 in the street. It included many children. The white driver & passengers got off the trolly.

Mr Mills and the other Black passengers were left.

There was a white crowd of 300 in the street. It included many children. The white driver & passengers got off the trolly.

Mr Mills and the other Black passengers were left.

The white crowd threw bricks and beat the black streetcar passengers with clubs. They dragged Mr Mills out of the car, but he got away. He ran down an alley.

This photo shows the chase. At the left edge you can see Japanese immigrant photographer Fujita running to keep up.

This photo shows the chase. At the left edge you can see Japanese immigrant photographer Fujita running to keep up.

At 5:35PM on July 28, 1919 the white crowd chased John Mills into a dead end. He had committed no crime. But they stoned him to death.

101 years ago today.

Immigrant photographer Jun Fujita created this historic image that became known as the first murder ever caught on film.

101 years ago today.

Immigrant photographer Jun Fujita created this historic image that became known as the first murder ever caught on film.

The family of Mr Mills sadly did not see any justice. When police arrived on the scene they recognized several white members of a local athletic club they knew, and chose not to arrest anyone.

One officer explained that he didn& #39;t consider them guilty "for they did not run."

One officer explained that he didn& #39;t consider them guilty "for they did not run."

The photographer was horrified by what he had witnessed– and caught on film. He reportedly flagged down a passing car and rushed Mr Mills to the hospital. But it was sadly too late to save Mr Mills& #39; life.

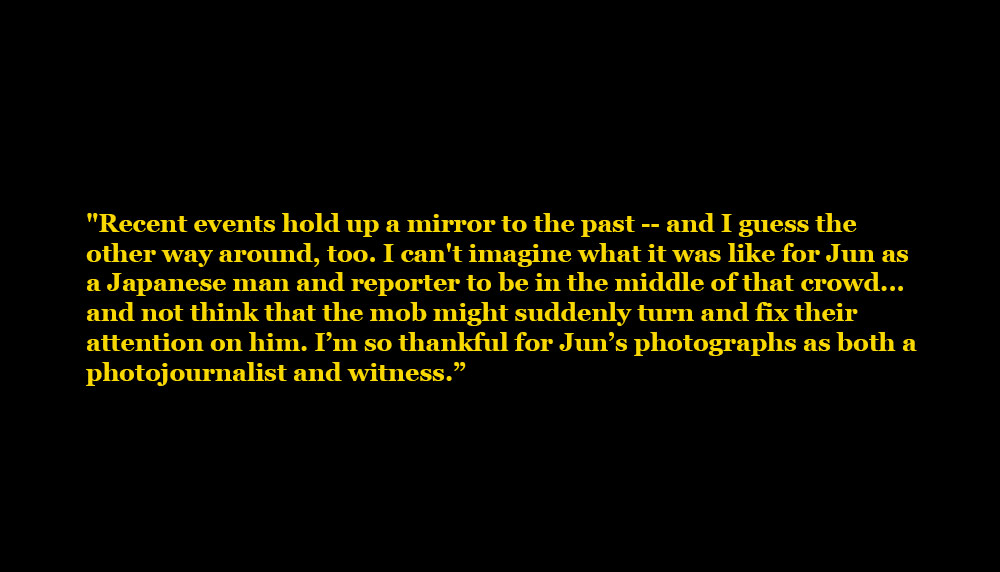

Fujita& #39;s family member @GrahamLeeAuthor tells me:

Fujita& #39;s family member @GrahamLeeAuthor tells me:

During the 1919 Chicago race riot, 28 Blacks and 15 whites died. Although most perpetrators were white, Chicago& #39;s white police didn& #39;t seem to arrest them.

A juror later complained: "What the ---- is the matter with the state’s attorney? Hasn’t he got any white cases to present?"

A juror later complained: "What the ---- is the matter with the state’s attorney? Hasn’t he got any white cases to present?"

After the race riot, Black Chicago would ultimately rebuild stronger and more self-sufficient than it ever was before.

One older long time resident who remembered the time after the riots after rebuilding told me "We didn& #39;t have to go outside the community for anything."

One older long time resident who remembered the time after the riots after rebuilding told me "We didn& #39;t have to go outside the community for anything."

The history of Chicago& #39;s 1919 race riot is a powerful reminder that racism can exist anywhere. Even in places that you would have thought were progressive on race. Violent racism was and is certainly not limited to the South.

We all need to work against it. Everywhere.

We all need to work against it. Everywhere.

Today the memory of John Mills and the injustice that befell him is immortalized in Jun Fujita& #39;s wrenching photograph.

His white-owned paper considered it unpublishable. But it would later help Chicago understand what happened when it was published in a 1922 report on the riot.

His white-owned paper considered it unpublishable. But it would later help Chicago understand what happened when it was published in a 1922 report on the riot.

Fujita ultimately became the target of racism himself–this time from the US government. They labeled him an "enemy alien" during WW II because he was from Japan.

His newspaper editors feared for his safety. He eventually got a gun, likely fearing mobs like the one he witnessed.

His newspaper editors feared for his safety. He eventually got a gun, likely fearing mobs like the one he witnessed.

See more images from Fujita& #39;s groundbreaking career as an immigrant photographer on Instagram. They provide some of the best record of life in the 1920s-1940s that survives today.

I encourage you to follow this account where new photos are posted often:

https://www.instagram.com/fujitabehindthecamera/">https://www.instagram.com/fujitabeh...

I encourage you to follow this account where new photos are posted often:

https://www.instagram.com/fujitabehindthecamera/">https://www.instagram.com/fujitabeh...

If you didn& #39;t know this story and think it& #39;s important or timely, consider sharing it. And if you don& #39;t want to miss one of my history threads, you can subscribe to my free substack.

My next history thread will be a joyful one. I absolutely promise. https://arlen.substack.com/ ">https://arlen.substack.com/">...

My next history thread will be a joyful one. I absolutely promise. https://arlen.substack.com/ ">https://arlen.substack.com/">...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter