An evening thread about Çatalhöyük, one of the oddest archaeological sites in the Middle East and one that tells us a lot about both the earliest history of cities, and the development of inequality and hierarchy in the earliest civilizations (1/20).

Çatalhöyük was an early "megasite" in what is now southern Turkey, peaking around 7000 BC with somewhere between 5,000-10,000 permanent residents--still small enough that people could subsist off of local foraging in what used to be a rich wetland environment.

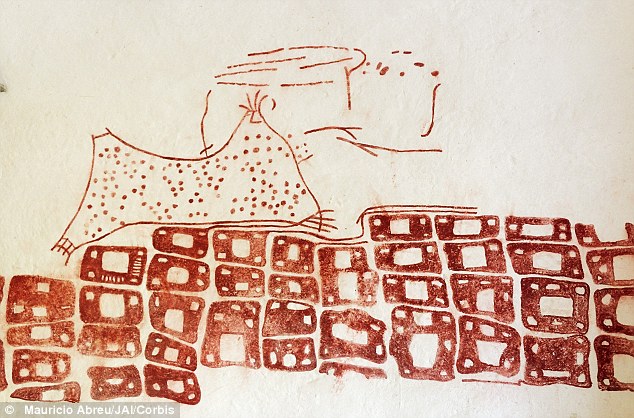

Excavations have been ongoing for decades at this point, with some neat finds: for example, one house has a wall decoration that has been described as (possibly) the world& #39;s first map, apparently detailing the settlement and a nearby volcano.

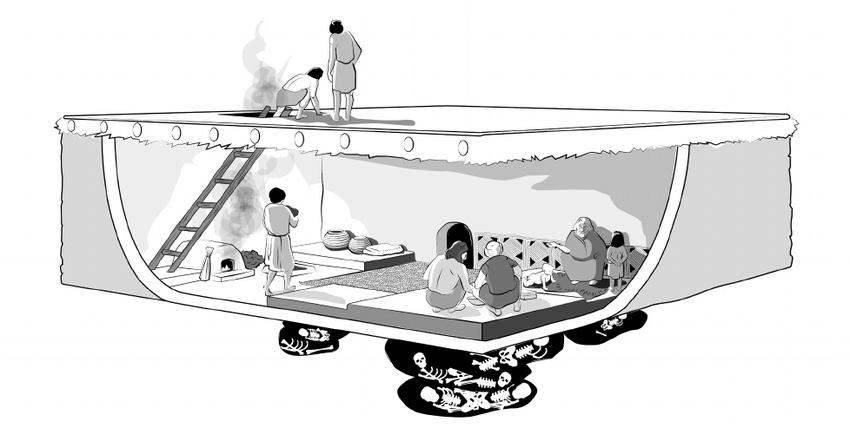

But it& #39;s what& #39;s missing that matters. Despite its size, "no public spaces, administrative buildings, elite quarters, or really any specialized facilities" have ever been uncovered. No temples, palaces, plazas, or writing--in short, none of the hallmarks of urban "civilization".

In fact, there weren& #39;t even public streets--people apparently got around by walking across each other& #39;s roofs, with ladders through the ceiling acting as primary access points for buildings.

As a result, the head of excavations at the site considers the label of "city" inappropriate, as it lacks all economic specialization, public works, and other features characteristic of, say, the later Mesopotamian city-states. He instead calls it "a very very large village".

This is strange, because villages...aren& #39;t supposed to be able to grow this large. Beyond a size of ~400 people, kin-based modes of social regulation and conflict resolution break down. We see either "village fission", where some people split off to form a new, smaller village...

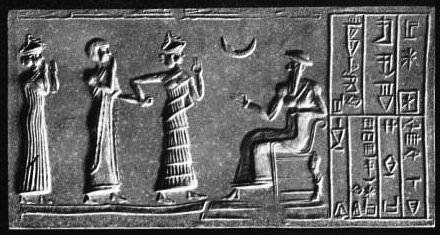

...or the development of "civilizational" institutions--law codes, courts, temples and palaces that direct and coordinate activity, and above all the entrenchment of inequality and some sort of elite--priestly, royal, or otherwise--often with writing to help manage it all.

This was once assumed to be a universal "civilizing" process, with urbanization (eventually) tending towards these institutions, so that some scholars have simply stated that "the first civilizations were the earliest and simplest forms of class societies".

Within the earliest cities, a "willingness to elaborate rituals, increase compartmentalization [i.e. separation by family, class, economic specialization], and expand basal units eroded norms of autonomy and egalitarianism" that had defined earlier, nomadic society.

(This transition was sometimes quite violent: several scholars have argued that the Ur "death pits" and other instances of early ritual human sacrifice were efforts by the first kings to terrorize a resistant, egalitarian-minded populace into submission.)

https://learning.hccs.edu/faculty/brett.furth/anth2302/additional-readings/dickson-2006">https://learning.hccs.edu/faculty/b...

https://learning.hccs.edu/faculty/brett.furth/anth2302/additional-readings/dickson-2006">https://learning.hccs.edu/faculty/b...

But Çatalhöyük suggests another possibility. Despite two millennia of existence, it never developed writing, any apparent mass rituals or public administration, or organized religion (though a widespread ox-cult has been suggested from the omnipresent bull decorations in homes)

Çatalhöyük "pushed the idea of an egalitarian village to its ultimate extreme": people apparently took every effort to avoid the creation of public institutions, even going as far as burying family members in their own homes rather than creating public cemeteries.

This may partially have been accomplished by an extremely insular social outlook: while Çatalhöyük& #39;s residents had no grand public monuments, they kept their homes immaculately clean, with one house interior being replastered at least 450 times!

According to one scholar, "the creation of house-centered society at Çatalhöyük led to an atomized, conservative, and inward-looking community that was resistant to social change". In this case, that social change would have been the establishment of class society.

But over time, population growth combined with the adoption of agriculture seem to have made stratification inevitable. Houses in Çatalhöyük had generally been similar in size, but later on some residents began to build large complexes, and streets began to appear.

How did the Çatalhöyük react to this growing inequality? They abandoned the site.

Late in the site& #39;s history, status goods like obsidian became more apparent, and craft specialization between households becomes apparent. Not long after, the population dispersed from Çatalhöyük.

Late in the site& #39;s history, status goods like obsidian became more apparent, and craft specialization between households becomes apparent. Not long after, the population dispersed from Çatalhöyük.

This was apparently not an isolated incident: "there was a consistent preference across Near Eastern settlements during the Neolithic period for options that did not result in a more hierarchical society".

Forced to choose between urban life and their egalitarian ideals, the residents of Çatalhöyük apparently chose the latter. This speaks to some important points: there exists a strong egalitarian drive in early humanity, inequality is not society& #39;s ironclad destiny.

In our own time, when most politicians have resigned themselves to ever-increasing inequality, Çatalhöyük reminds us that this is not inevitable: stratification is not the unavoidable destiny of society, but a deliberate choice, something we *can* stop, even reverse.

(/end)

(/end)

(All quotes and screenshots in this thread are from "Killing Civilization: A Reassessment of Early Urbanism and its Consequences" by Dr. Justin Jenning of the University of Toronto)

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter

![Within the earliest cities, a "willingness to elaborate rituals, increase compartmentalization [i.e. separation by family, class, economic specialization], and expand basal units eroded norms of autonomy and egalitarianism" that had defined earlier, nomadic society. Within the earliest cities, a "willingness to elaborate rituals, increase compartmentalization [i.e. separation by family, class, economic specialization], and expand basal units eroded norms of autonomy and egalitarianism" that had defined earlier, nomadic society.](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EdaN4upX0AABDLP.jpg)