Today is an exciting day for international macro! The world gets to see an @IMFNews discussion note, a new working paper, a blog AND a new dataset all on the topic of dominant currency pricing

Picture the scene. You& #39;re an economic policymaker in an emerging market. Some bad stuff is happening (hi covid) and you& #39;re searching around for ways to help the economy cope.

Along comes an economist, who suggests that you let the exchange rate depreciate. They admit that WILL make imports more expensive... but exporters will ALSO become more competitive! Great! Jobs! Awesome! Jobs!

You take a deep breath and accept the advice. You push a magic button* and the value of your currency plunges...

...and then you watch

*this is a tweet thread not an accurate depiction of central bank intervention to affect exchange rates

...and then you watch

*this is a tweet thread not an accurate depiction of central bank intervention to affect exchange rates

...and something weird happens. Imports start collapsing (everyone hates you) but exports... just aren& #39;t really... doing much?

ENTER @GITAGOPINATH

And she is sorry to inform you that the exchange rate devaluation probably won& #39;t be as helpful as you hoped.

And she is sorry to inform you that the exchange rate devaluation probably won& #39;t be as helpful as you hoped.

Devaluation was supposed to change relative prices.

By reducing export prices, foreigners were supposed to buy more.

Before: 1 face mask costs 10 lira to make, priced at 10 pesos

After: 1 face mask costs 10 lira, priced at 5 pesos

price https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👇" title="Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten">, sales

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👇" title="Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten">, sales  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👆" title="Rückhand Zeigefinger nach oben" aria-label="Emoji: Rückhand Zeigefinger nach oben">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👆" title="Rückhand Zeigefinger nach oben" aria-label="Emoji: Rückhand Zeigefinger nach oben">

By reducing export prices, foreigners were supposed to buy more.

Before: 1 face mask costs 10 lira to make, priced at 10 pesos

After: 1 face mask costs 10 lira, priced at 5 pesos

price

BUT. Companies use these PESKY things called contracts. When they trade, they agree prices in advance, and in the short-term those prices tend to be fixed.

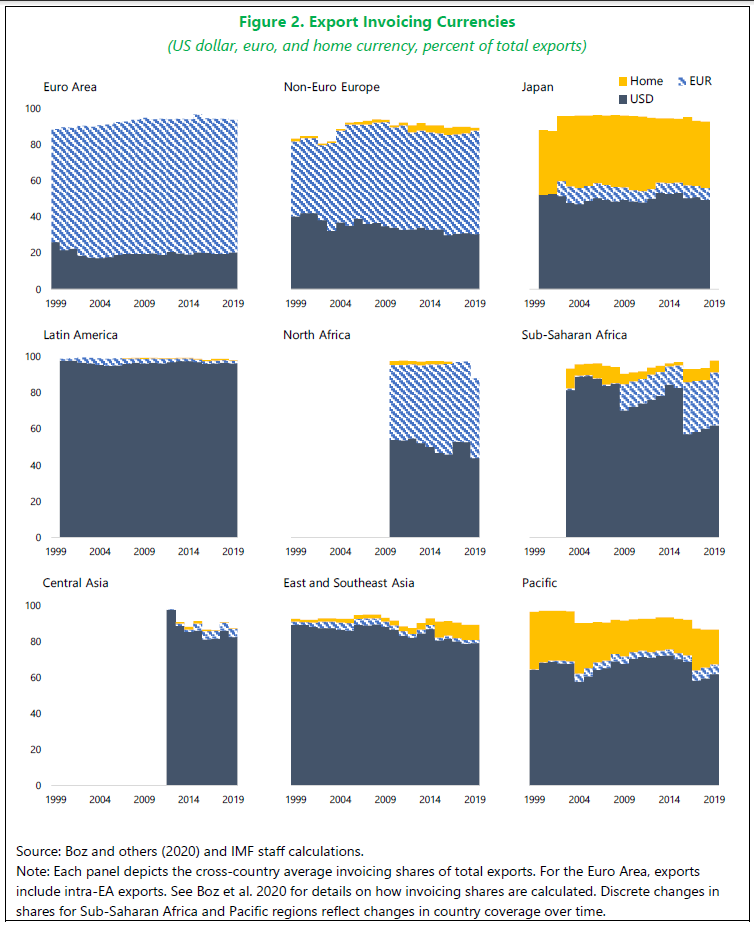

Crucially, often those prices are set NOT in pesos or lira, but in DOLLARS

Crucially, often those prices are set NOT in pesos or lira, but in DOLLARS

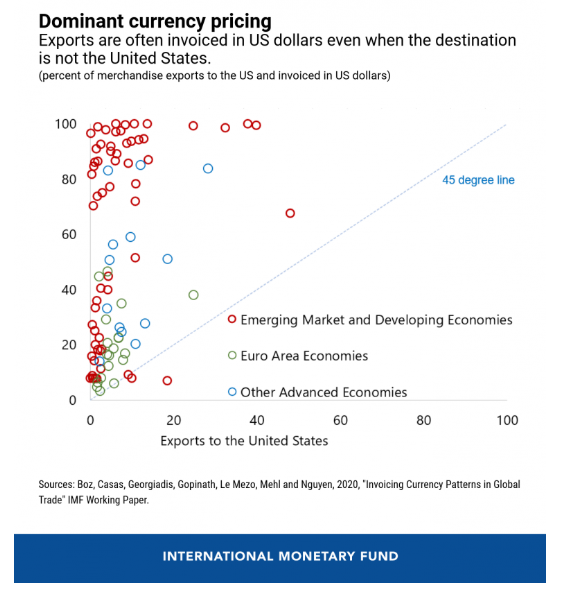

This first chart shows that for many emerging market and developing economies, a country& #39;s share of trade invoiced in dollars MASSIVELY outweighs its share of trade with the US

So what does that mean?

WELL. It means that a currency devaluation won& #39;t work in the way that you want.

So

1. you& #39;re making face masks, and they& #39;re priced in dollars

2. your currency depreciates--BUT the prices are stuck in dollars

3. so foreigners face the same prices...

WELL. It means that a currency devaluation won& #39;t work in the way that you want.

So

1. you& #39;re making face masks, and they& #39;re priced in dollars

2. your currency depreciates--BUT the prices are stuck in dollars

3. so foreigners face the same prices...

The import adjustment still happens, as the depreciation means that imports (also priced in dollars) become much more expensive.

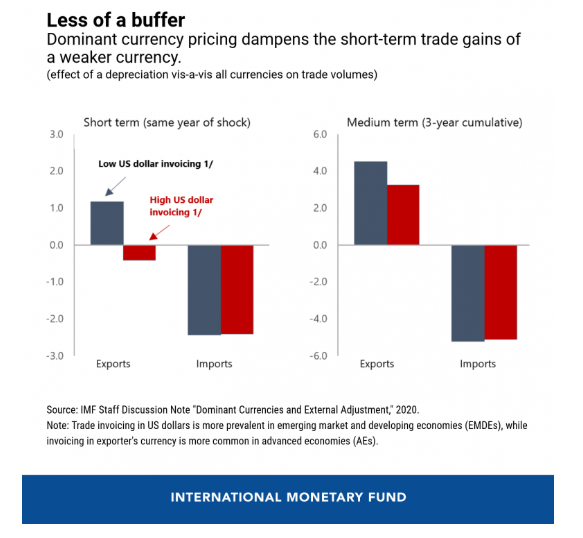

Overall, this dollar pricing dampens the effect of exchange rate movements IN THE SHORT TERM.

@GitaGopinath and others at the @IMFNews have estimated how much:

@GitaGopinath and others at the @IMFNews have estimated how much:

Now, for you (the policymaker) this is frustrating...

and... THERE IS ANOTHER PROBLEM

because companies use the dollar for purposes other than trade. They also use it when BORROWING.

currency devaluation https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👉" title="Rückhand Zeigefinger nach rechts" aria-label="Emoji: Rückhand Zeigefinger nach rechts">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👉" title="Rückhand Zeigefinger nach rechts" aria-label="Emoji: Rückhand Zeigefinger nach rechts">

liabilities https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👆" title="Rückhand Zeigefinger nach oben" aria-label="Emoji: Rückhand Zeigefinger nach oben">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👆" title="Rückhand Zeigefinger nach oben" aria-label="Emoji: Rückhand Zeigefinger nach oben">

access to new finance https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👇" title="Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👇" title="Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten">

cost of servicing debt https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👆" title="Rückhand Zeigefinger nach oben" aria-label="Emoji: Rückhand Zeigefinger nach oben">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👆" title="Rückhand Zeigefinger nach oben" aria-label="Emoji: Rückhand Zeigefinger nach oben">

and... THERE IS ANOTHER PROBLEM

because companies use the dollar for purposes other than trade. They also use it when BORROWING.

currency devaluation

liabilities

access to new finance

cost of servicing debt

For companies that are EXPORTING, borrowing and pricing in dollars makes some sense. When the currency depreciates, your revenue (priced in dollars) and your liabilities (also in dollars) are matched.

A natural hedge!

A natural hedge!

For companies that are importing and borrowing in dollars, though, there isn& #39;t a natural hedge.

Devaluation https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👉" title="Rückhand Zeigefinger nach rechts" aria-label="Emoji: Rückhand Zeigefinger nach rechts"> imports more expensive AND debt servicing become more onerous.

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👉" title="Rückhand Zeigefinger nach rechts" aria-label="Emoji: Rückhand Zeigefinger nach rechts"> imports more expensive AND debt servicing become more onerous.

Devaluation

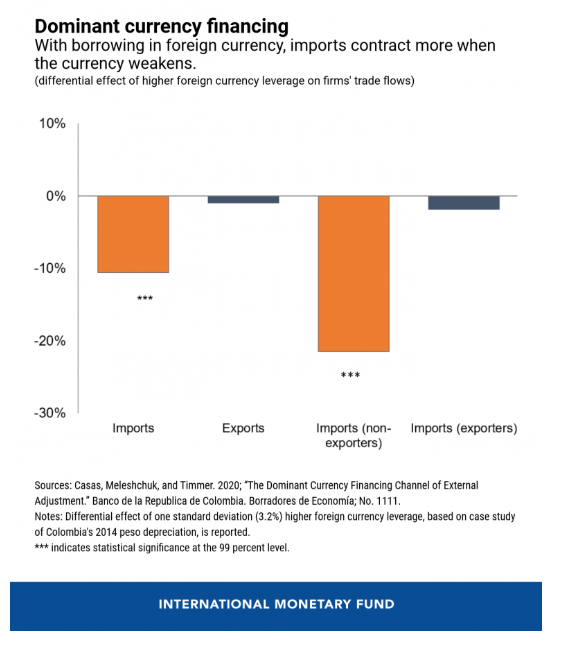

The @IMFNews folks look at Colombian companies after their exchange rate depreciated...

This chart (y axis) shows the difference between companies that do lots of $ borrowing and those who do less

MORE $ borrowing is associated with a BIGGER drop in imports after a devaluation

This chart (y axis) shows the difference between companies that do lots of $ borrowing and those who do less

MORE $ borrowing is associated with a BIGGER drop in imports after a devaluation

Do read their blog (which includes links to the staff discussion note/working paper/dataset): https://blogs.imf.org/2020/07/20/currencies-and-crisis-how-dominant-currencies-limit-the-impact-of-exchange-rate-flexibility/">https://blogs.imf.org/2020/07/2...

the staff discussion note in particular has some killer charts

https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Staff-Discussion-Notes/Issues/2020/07/16/Dominant-Currencies-and-External-Adjustment-48618">https://www.imf.org/en/Public...

https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Staff-Discussion-Notes/Issues/2020/07/16/Dominant-Currencies-and-External-Adjustment-48618">https://www.imf.org/en/Public...

And if you want to hear some clever people talk about this (and me) there will be a webinar in FIVE MINUTES https://twitter.com/i/broadcasts/1RDGlrpwjpVxL">https://twitter.com/i/broadca...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter