Humanity’s history is a battle against the microbes. And for most of our history we were losing very decisively.

My new post – and visualization – on how vaccines allowed us to make progress against recurring epidemics of infectious diseases:

http://OurWorldInData.org/microbes-battle-science-vaccines">https://OurWorldInData.org/microbes-...

My new post – and visualization – on how vaccines allowed us to make progress against recurring epidemics of infectious diseases:

http://OurWorldInData.org/microbes-battle-science-vaccines">https://OurWorldInData.org/microbes-...

For most of our history we were losing very decisively against the microbes.

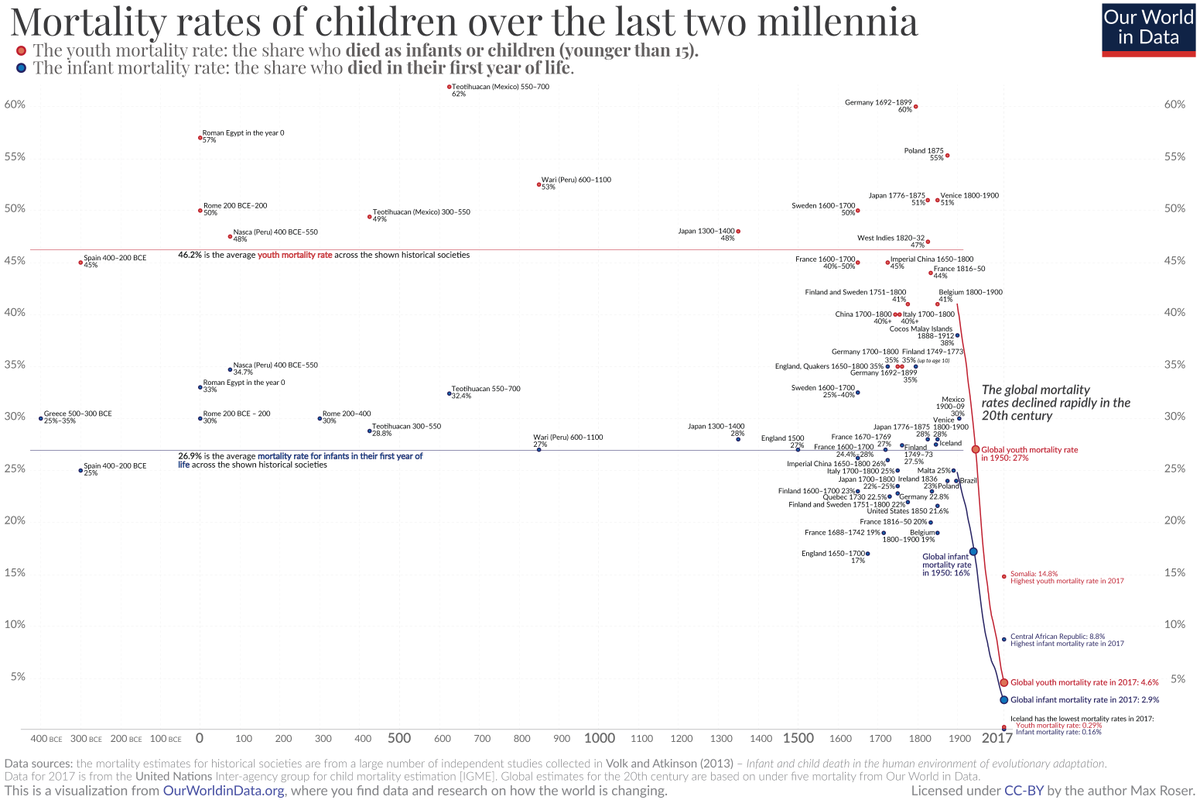

No matter where or when they were born, around half of all children died. Billions of them died from infectious diseases.

[in detail here https://ourworldindata.org/child-mortality-in-the-past]">https://ourworldindata.org/child-mor...

No matter where or when they were born, around half of all children died. Billions of them died from infectious diseases.

[in detail here https://ourworldindata.org/child-mortality-in-the-past]">https://ourworldindata.org/child-mor...

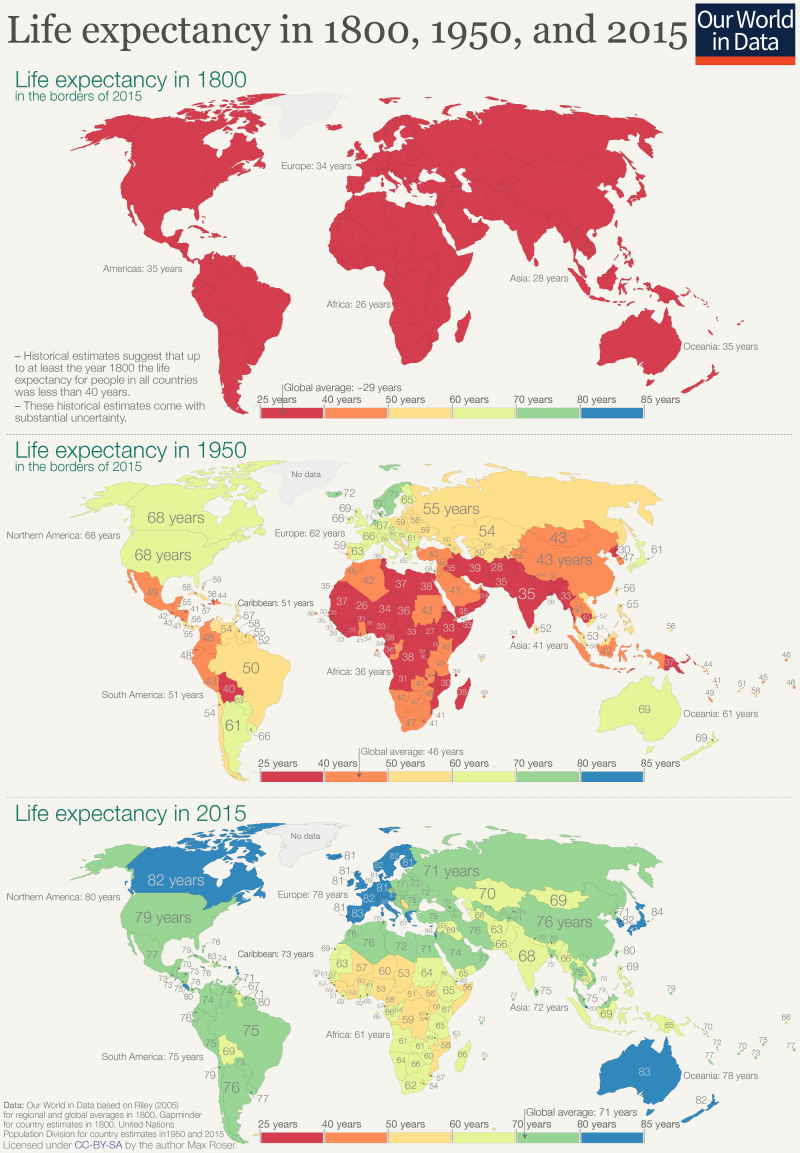

The world today is obviously very different. Infectious diseases are the cause of fewer than 1-in-6 deaths and as we learned how to protect ourselves from germs life expectancy doubled in every world region.

The global average is now 73 years.

[see https://ourworldindata.org/life-expectancy-globally]">https://ourworldindata.org/life-expe...

The global average is now 73 years.

[see https://ourworldindata.org/life-expectancy-globally]">https://ourworldindata.org/life-expe...

Science laid the foundation for our success. 150 years ago nobody knew where diseases came from.

The widely accepted idea was that Miasma, a form of “bad air”, causes disease. The word malaria – ‘mal aria’ ‘bad air’ in medieval Italian – remains with us today.

The widely accepted idea was that Miasma, a form of “bad air”, causes disease. The word malaria – ‘mal aria’ ‘bad air’ in medieval Italian – remains with us today.

In the 19th century humanity learned that not noxious air, but specific germs cause infectious diseases.

The germ theory of disease was a scientific breakthrough.

Not the only, but perhaps the most important technical innovation in our fight against microbes were vaccines.

The germ theory of disease was a scientific breakthrough.

Not the only, but perhaps the most important technical innovation in our fight against microbes were vaccines.

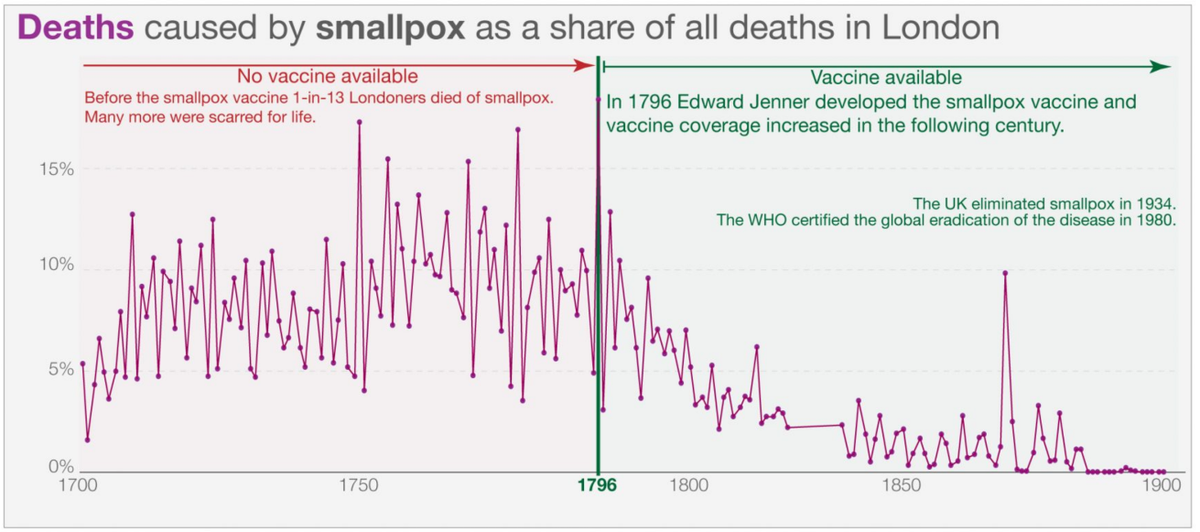

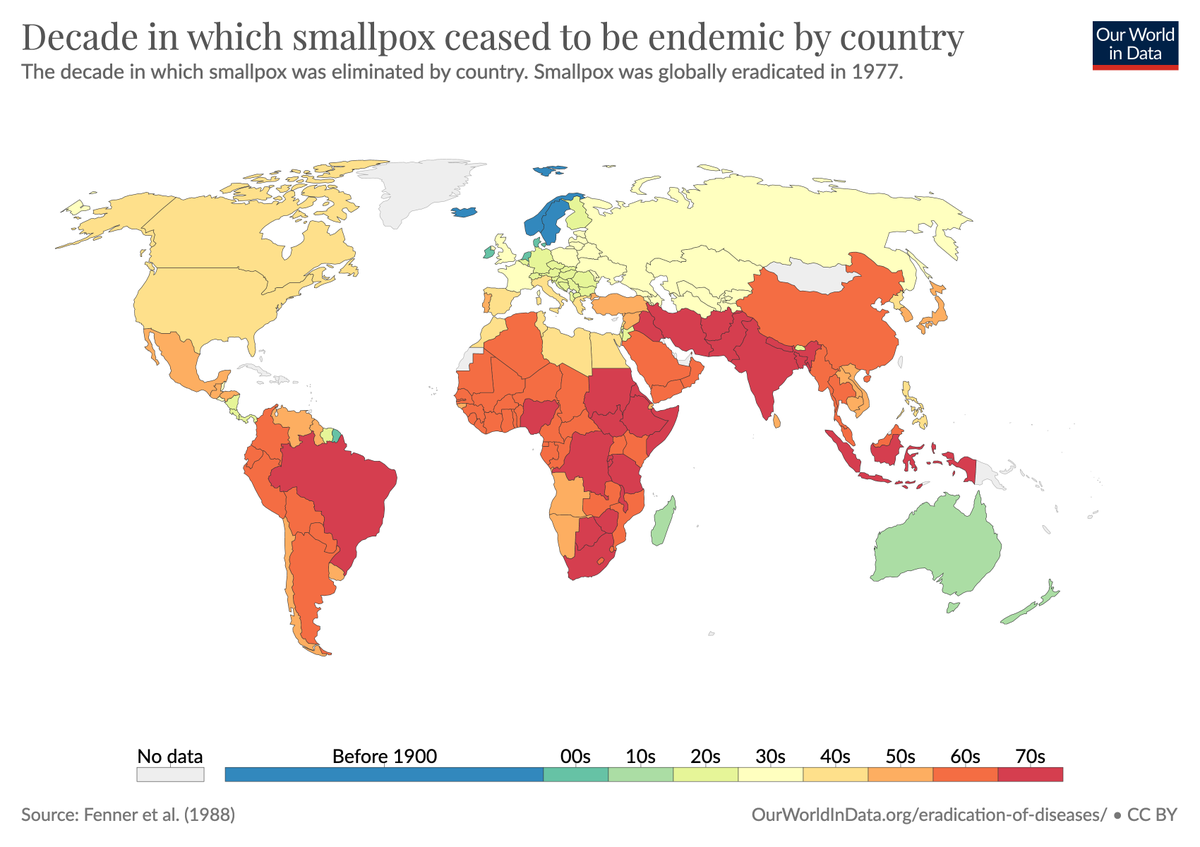

Smallpox was one of the worst killers in our history. In the last hundred years of its existence smallpox killed at least half a billion people.

Even more people were disfigured and blinded by the disease for the rest of their lives.

Even more people were disfigured and blinded by the disease for the rest of their lives.

Humanity never found an effective treatment against smallpox, but we invented something even better: a vaccine, the very first vaccine ever.

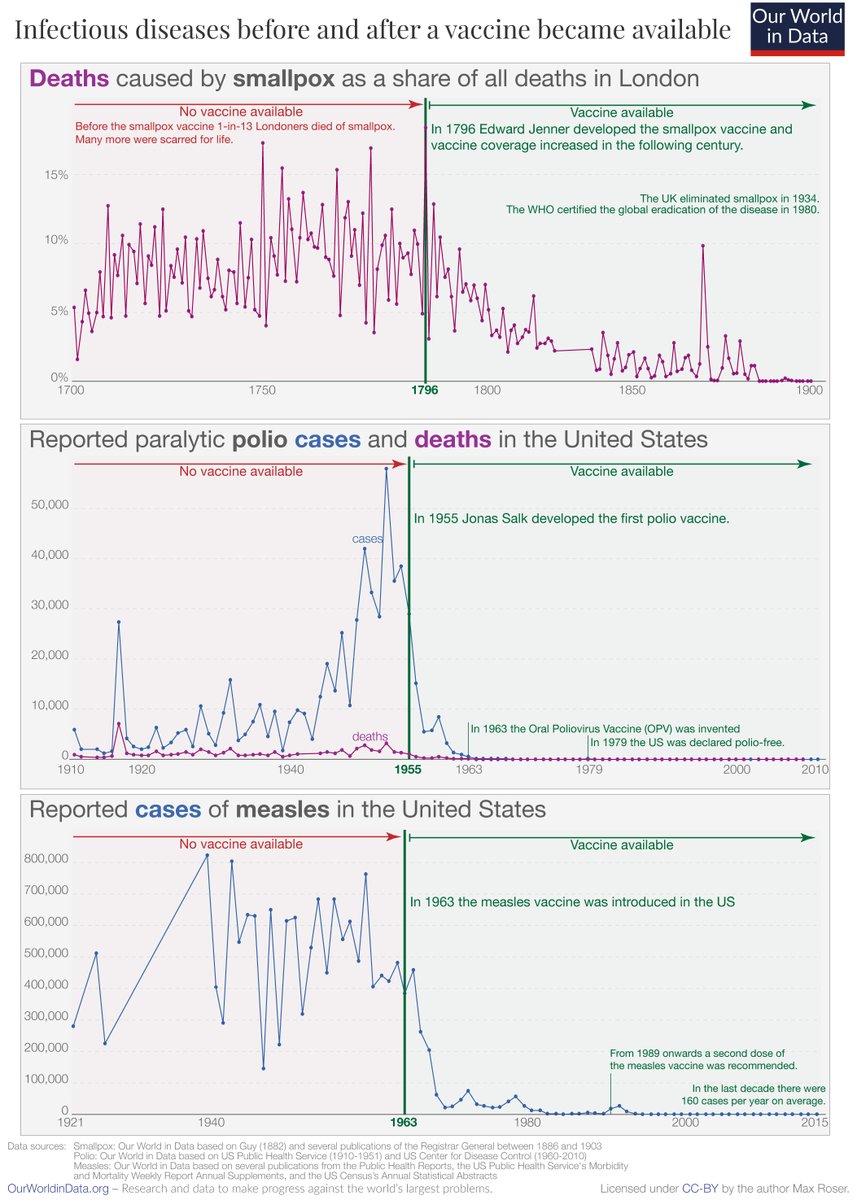

As the chart shows, the case count fell as the vaccine reached more and more people and improved over time.

As the chart shows, the case count fell as the vaccine reached more and more people and improved over time.

Eventually the disease was eliminated in entire countries, then entire continents, and today the disease does not exist anywhere in the world.

The smallpox vaccine made it possible to completely eradicate the disease (saving the lives of around 150 to 200 million people since).

The smallpox vaccine made it possible to completely eradicate the disease (saving the lives of around 150 to 200 million people since).

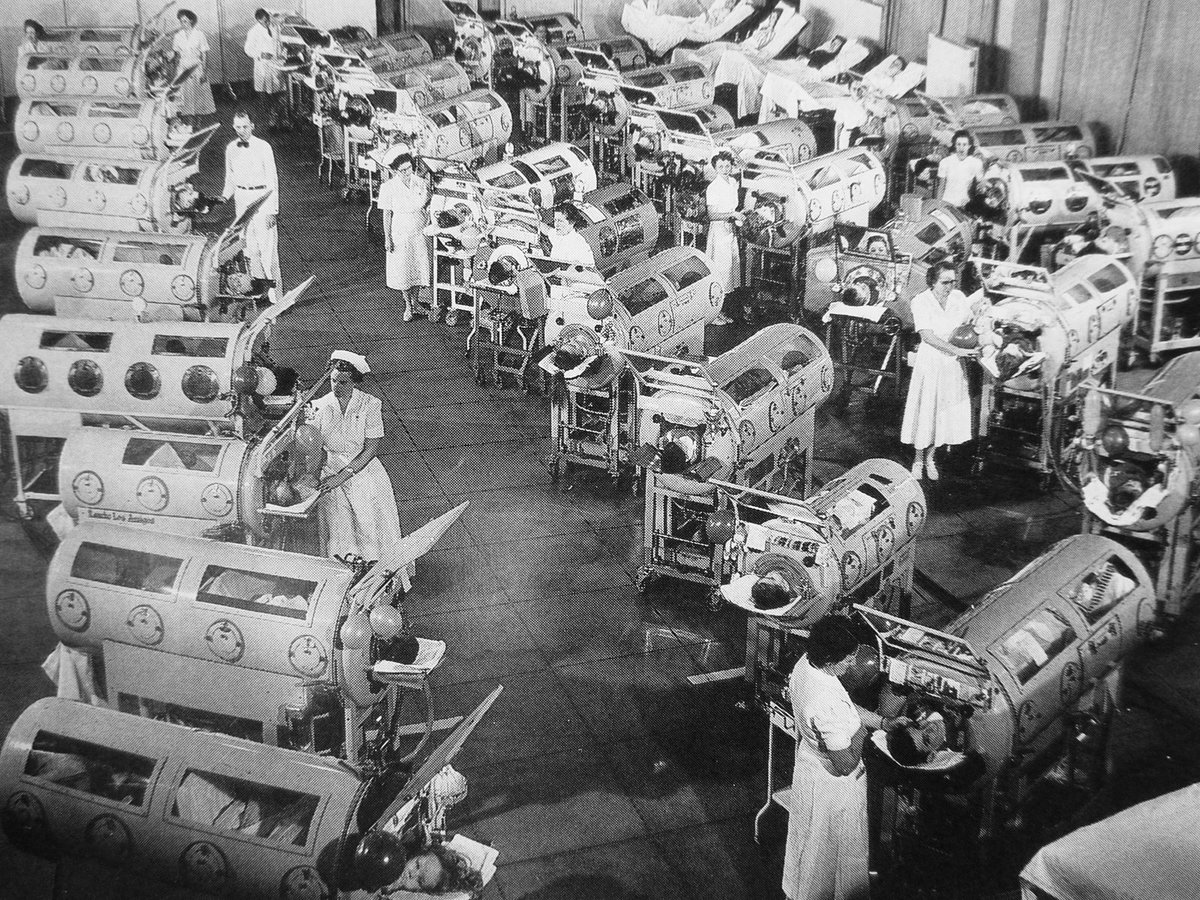

Polio epidemics spread panic at a time that many today can still remember.

Polio is an infectious disease, contracted predominantly by children, that can lead to the permanent paralysis of various body parts and ultimately death by immobilizing the patient’s breathing muscles.

Polio is an infectious disease, contracted predominantly by children, that can lead to the permanent paralysis of various body parts and ultimately death by immobilizing the patient’s breathing muscles.

Patients paralyzed by polio could only survive when they were stuck in large, mechanical breathing apparatuses: the so-called ‘iron lungs’.

The machine decreased the pressure inside the box, to induce inhalation, before returning to the outside pressure, to induce exhalation.

The machine decreased the pressure inside the box, to induce inhalation, before returning to the outside pressure, to induce exhalation.

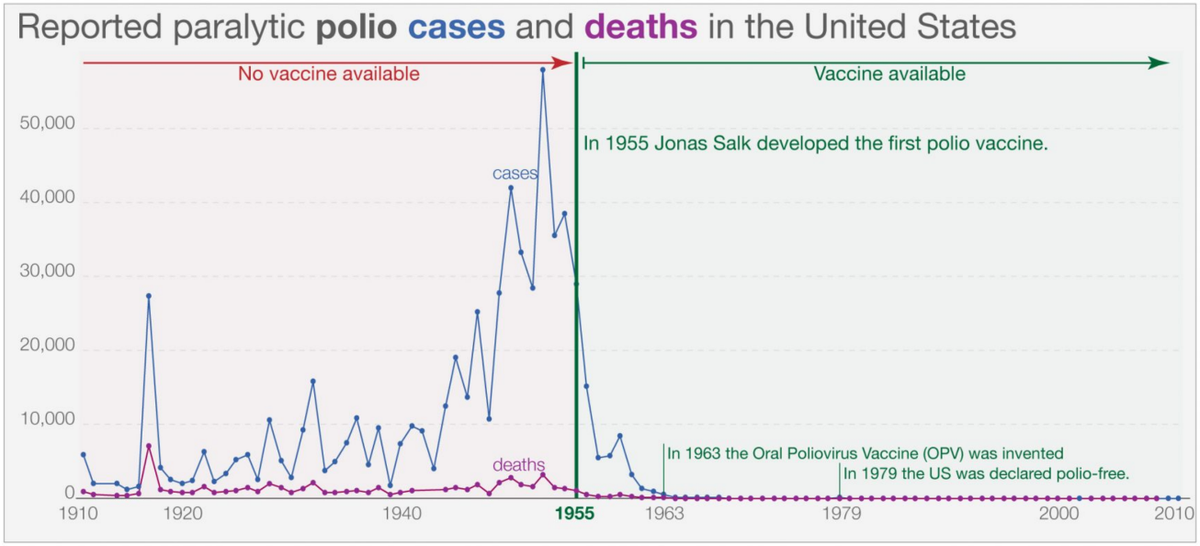

The outbreaks ended in 1955 when Jonas Salk developed the polio vaccine.

When it was announced on April 12 it was celebrated as “more than a scientific achievement” according to Salk’s biographer Carter: The vaccine “was a folk victory, an occasion for pride and jubilation…

When it was announced on April 12 it was celebrated as “more than a scientific achievement” according to Salk’s biographer Carter: The vaccine “was a folk victory, an occasion for pride and jubilation…

people observed moments of silence, rang bells, honked horns, blew factory whistles, fired salutes,… took the rest of the day off, closed their schools or convoked fervid assemblies therein, drank toasts, hugged children, attended church, and smiled at strangers.”

As the chart shows, these celebrations were not misplaced.

Over the coming years vaccination campaigns reached many American children and the terrible epidemics ended. By 1979 the US was declared polio-free.

Over the coming years vaccination campaigns reached many American children and the terrible epidemics ended. By 1979 the US was declared polio-free.

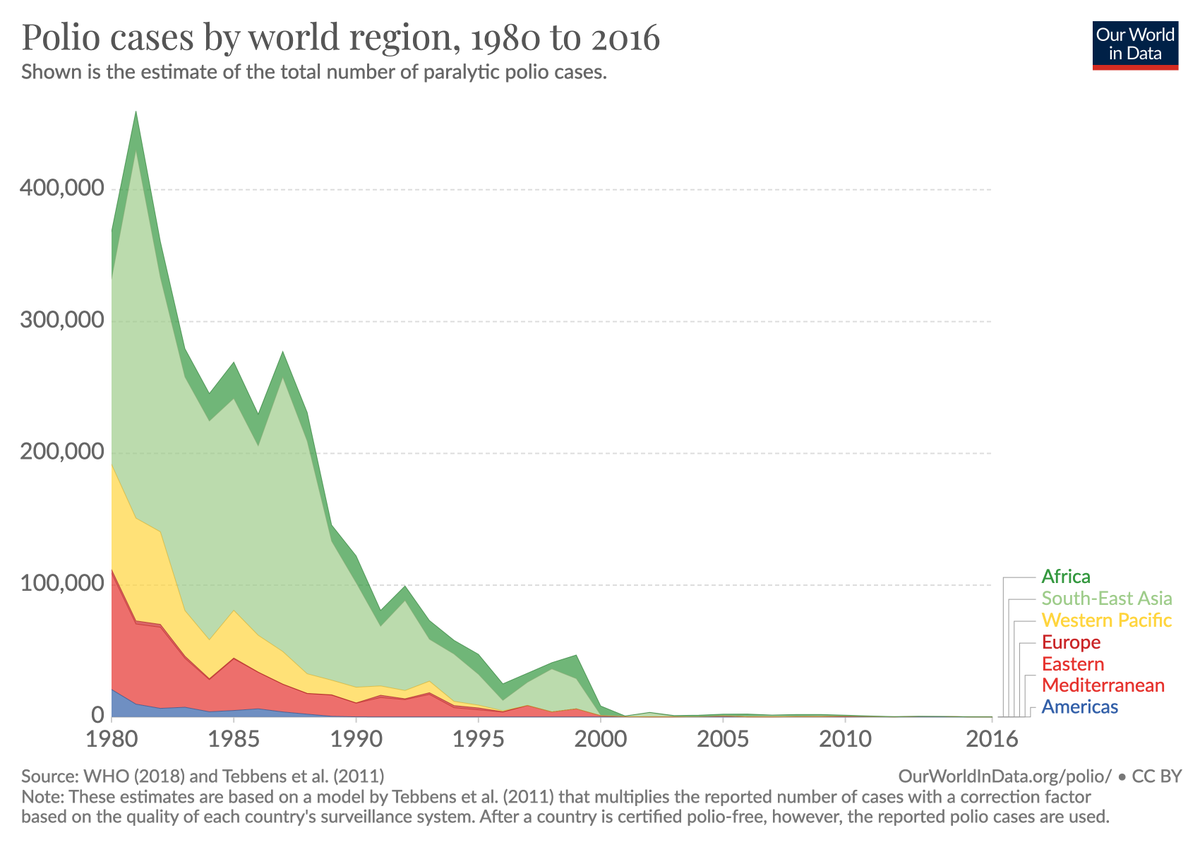

Today our generation has the chance to achieve for polio what has been achieved for smallpox: global eradication.

Thanks to the vaccine, humanity has made massive progress towards this goal. From more than three-hundred-thousand paralytic cases in the 1980s down to hundreds.

Thanks to the vaccine, humanity has made massive progress towards this goal. From more than three-hundred-thousand paralytic cases in the 1980s down to hundreds.

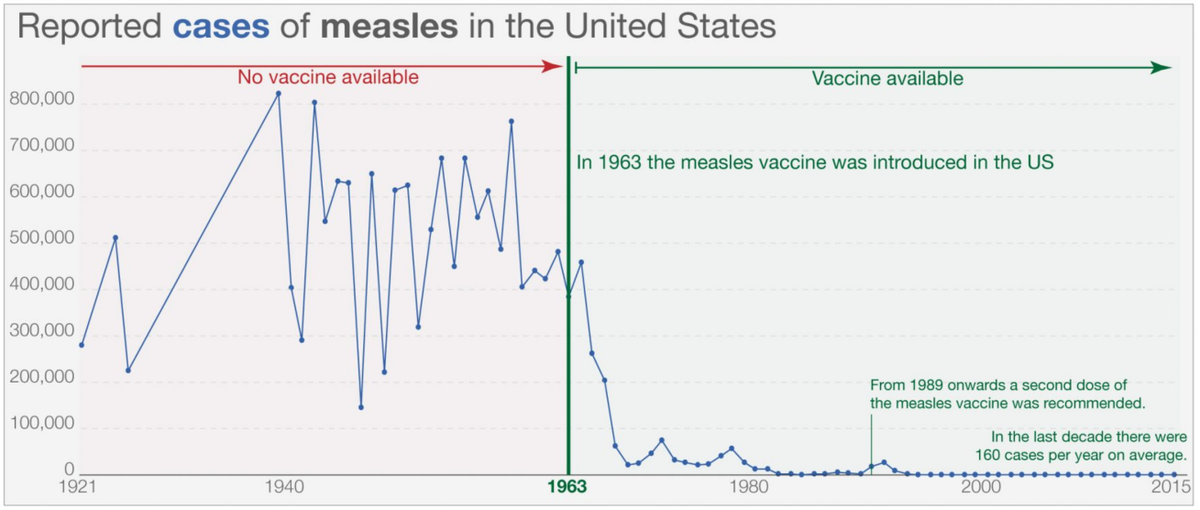

Measles is both very deadly and extremely contagious.

The virus can travel dozens of meters. Published estimates of the (these days much discussed) basic reproduction number (R0) – the average number of secondary cases arising from each case – range from 3.7 up to 203.

The virus can travel dozens of meters. Published estimates of the (these days much discussed) basic reproduction number (R0) – the average number of secondary cases arising from each case – range from 3.7 up to 203.

Before the introduction of the measles vaccine in 1963 major epidemics occurred every 2–3 years and measles caused an estimated 2.6 million deaths each year.

Today, 85% of one-year olds receive the vaccine and the number of deaths has fallen to 95,000 in the latest data.

Today, 85% of one-year olds receive the vaccine and the number of deaths has fallen to 95,000 in the latest data.

The measles vaccine too changed world history and the history of millions of families.

The chart shows how rapidly we made progress against this killer after the invention of the vaccine. Once it was introduced, the large outbreaks came to an end.

The chart shows how rapidly we made progress against this killer after the invention of the vaccine. Once it was introduced, the large outbreaks came to an end.

When humanity achieves very substantial progress it can become difficult to understand what the problems were that we made progress against.

Infectious diseases that once disfigured, pained, paralyzed, and killed many of our ancestors have disappeared so far from our lives and memories that some today can afford the luxury of disregarding or even avoiding vaccination against dangerous diseases.

Now as we face the COVID-19 pandemic, it is the first time for many of us that we experience for one infectious disease what our ancestors experienced for a whole range of dangerous diseases.

We are facing a pathogen that we have no treatment for and no protection from.

We are facing a pathogen that we have no treatment for and no protection from.

The responses from South Korea, Vietnam, and Germany show that it is already possible to fight the pandemic successfully even before we have a vaccine.

Korea – http://ourworldindata.org/covid-exemplar-south-korea

Vietnam">https://ourworldindata.org/covid-exe... – http://ourworldindata.org/covid-exemplar-vietnam

Germany">https://ourworldindata.org/covid-exe... – http://ourworldindata.org/covid-exemplar-germany">https://ourworldindata.org/covid-exe...

Korea – http://ourworldindata.org/covid-exemplar-south-korea

Vietnam">https://ourworldindata.org/covid-exe... – http://ourworldindata.org/covid-exemplar-vietnam

Germany">https://ourworldindata.org/covid-exe... – http://ourworldindata.org/covid-exemplar-germany">https://ourworldindata.org/covid-exe...

But to end the suffering that COVID-19 causes our best hope is a vaccine against the virus.

Today’s results from CanSino and the University of Oxford are encouraging!

Here is my ongoing thread on it https://twitter.com/MaxCRoser/status/1243590284455350278">https://twitter.com/MaxCRoser...

Today’s results from CanSino and the University of Oxford are encouraging!

Here is my ongoing thread on it https://twitter.com/MaxCRoser/status/1243590284455350278">https://twitter.com/MaxCRoser...

And until we get there we’ll monitor the data on the pandemic closely and learn together from it.

Our best strategy in the age-old fight against the germs is our collaborative, data-based effort to study the world around us and within us. Our best strategy is science.

/end/

Our best strategy in the age-old fight against the germs is our collaborative, data-based effort to study the world around us and within us. Our best strategy is science.

/end/

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter