As with the oaks, the birches have two native species and a hybrid. But Betula is even trickier, because the genetics are more complicated.

Linnaeus didn’t make very many mistakes, and he considered both our two birches to represent extreme forms of one variable species, which he called Betula alba. What he couldn’t know is that this lumped together sexually incompatible plants with different chromosome counts.

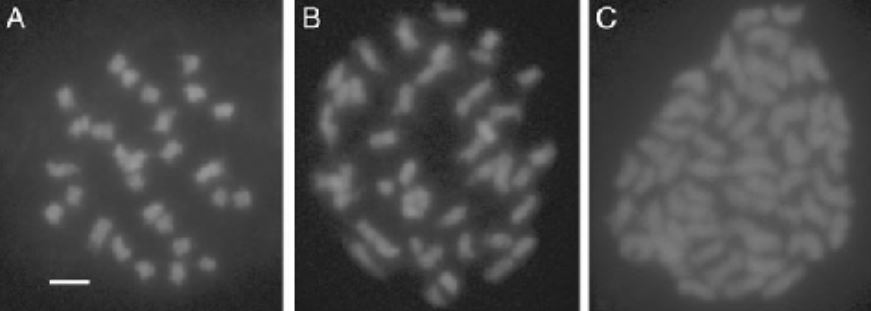

We now know that there are two distinct species, with different chromosome numbers (ploidies). Betula pendula has 2n = 28 (a diploid, Fig. A) and Betula pubescens has 2n = 56 (a tetraploid, Fig. C). The image in the middle is a triploid hybrid (2n = 14 + 28 = 42, Fig. B)

The two species have different ecological niches: Betula pendula in warmer, drier habitats and B. pubescens in colder, wetter sites. This is reflected in their geographic distributions: in Scotland, for instance, B. pubescens is the only species you’ll find in the north and west

We’ll start with the easiest feature, but Sod’s Law is at work here, because it’s not unambiguous. Look at the young twigs (x10). If they are densely velvety with very short, fine (puberulent) hairs, then you have Betula pubescens (hence the name, left).

Unfortunately, you can’t conclude that hairless twigs means B. pendula (right), because some forms of B. pubescens (despite their name) have hairless twigs.

So how to proceed? A two-stage process is most effective, starting with easy, accessible characters. Find a mature individual (more than, say, 6m tall) and observe it from a distance. Does the canopy have slender twigs, many of which hang almost vertically downwards? Or not.

Next, look at the base of the trunk of a mature individual. Is the bark broken up by deep, corky fissures into large, dark grey blocks. Or is the trunk smooth right down to the ground.

A big difference between birch and oak is that birch produces new leaves from the shoot tip throughout the growing season (oak leaves appear in just one or two (occasionally 3) discrete bursts). Terminal birch leaves differ in both size and shape as the summer progresses.

It is important, therefore to use the less variable leaves from the (lateral) short-shoots rather than the terminal leaf. There are two things we need to note. First, is the leaf tip acuminate (left) or not (right) ?

Now look at the marginal leaf-teeth. Do the big teeth have smaller teeth upon them (left), or are all the teeth un-toothed (right, even though the teeth may differ somewhat in size )?

OK. So here’s the initial, rough-and-ready scoring scheme:

Slender twigs hanging almost vertically down = 1;

not so = 2

Basal bark black and chunky = 1; not so = 2

Leaf tip acuminate = 1; not so = 2.

Leaf teeth with teeth = 1; not so =2

Slender twigs hanging almost vertically down = 1;

not so = 2

Basal bark black and chunky = 1; not so = 2

Leaf tip acuminate = 1; not so = 2.

Leaf teeth with teeth = 1; not so =2

Add your 4 scores together.

Total = 4= Betula pendula,

Total = 8 = B. pubescens,

Total = 5, 6 or 7 = something intermediate (details later)

Total = 4= Betula pendula,

Total = 8 = B. pubescens,

Total = 5, 6 or 7 = something intermediate (details later)

You may want to stop at this point, but there are more useful features to investigate. These have to do with the female catkins and with more detailed measurements on the leaves. Break open a female catkin (or find an old but intact one on the ground). Look closely (x10).

Start with the fruits: there is a pair of papery wings and a nut in the middle. On the top of the nut look very closely at the 2 stigmas (x10). Do the wings clearly over-top the stigmas (left) or not (right) ?

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter