1/ If you want to know how bitcoin/crypto will fare amidst global economic chaos, you should brush up on QE, MMT, and inflation.

The best and simplest explainer I& #39;ve read on this subject is the master class from @LynAldenContact.

https://www.lynalden.com/quantitative-easing-mmt-inflation/

Summary">https://www.lynalden.com/quantitat... https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👇" title="Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👇" title="Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten">

The best and simplest explainer I& #39;ve read on this subject is the master class from @LynAldenContact.

https://www.lynalden.com/quantitative-easing-mmt-inflation/

Summary">https://www.lynalden.com/quantitat...

2/ Credit for all good ideas/charts goes to Lyn, but I’ll offer some commentary as well.

PART 1: Gov’t Debt 101 & Why the Fed is All That’s Left

PART 2: Inevitability of QE Infinity & Inflation Risk

(I haven& #39;t seen any attempts to steel man the idea QE infinity is *inevitable*)

PART 1: Gov’t Debt 101 & Why the Fed is All That’s Left

PART 2: Inevitability of QE Infinity & Inflation Risk

(I haven& #39;t seen any attempts to steel man the idea QE infinity is *inevitable*)

3/ tl;dr: quantitative easing (aka QE, central bank asset purchases, debt monetization, etc.) has historically led to consumer price inflation.

BUT we haven’t seen it recently. What gives? Is it different this time(tm)?

It’s complicated, but it& #39;s 100% "print or bust."

BUT we haven’t seen it recently. What gives? Is it different this time(tm)?

It’s complicated, but it& #39;s 100% "print or bust."

4/ Super Remedial Debt 101:

Governments issue debt to pay for things they can’t afford from tax receipts alone. Infrastructure projects, Medicare, tax cuts, etc.

This is true for nations (e.g. U.S. Treasuries), but it also extends to smaller governments (e.g. muni bonds).

Governments issue debt to pay for things they can’t afford from tax receipts alone. Infrastructure projects, Medicare, tax cuts, etc.

This is true for nations (e.g. U.S. Treasuries), but it also extends to smaller governments (e.g. muni bonds).

5/ Balanced budgets are not a "need to have” if people believe in your government.

The mere fact governments *can* tax people (and eventually service debt) attracts buyers.

This is particularly true when debt is issued to pay for productive investments (i.e. growth).

The mere fact governments *can* tax people (and eventually service debt) attracts buyers.

This is particularly true when debt is issued to pay for productive investments (i.e. growth).

6/ It doesn’t matter if governments *actually pay back debt at maturity.*

In fact, investors usually won’t demand principal back unless something has gone very wrong (more later).

Instead, they often roll maturing investments into new debt investments.

In fact, investors usually won’t demand principal back unless something has gone very wrong (more later).

Instead, they often roll maturing investments into new debt investments.

7/ This is why governments can hypothetically run “huge" deficits forever.

Three conditions:

+ GDP growth matches debt growth

+ lenders lend at predictable pace (no adverse shocks)

+ interest payments don’t overwhelm total spending

If you meet those conditions, you’re good.

Three conditions:

+ GDP growth matches debt growth

+ lenders lend at predictable pace (no adverse shocks)

+ interest payments don’t overwhelm total spending

If you meet those conditions, you’re good.

8/ If not, you *need* to print money to pay for deficits.

That’s where the U.S. is today:

+ Debt:GDP continues to spike to historic levels

+ we’re running out of buyers for U.S. Treasuries

+ things are even worse at state and local levels https://brrr.money/ ">https://brrr.money/">...

That’s where the U.S. is today:

+ Debt:GDP continues to spike to historic levels

+ we’re running out of buyers for U.S. Treasuries

+ things are even worse at state and local levels https://brrr.money/ ">https://brrr.money/">...

9/ The brilliance of @LynAldenContact& #39;s piece is the ELI5 she does on each source of T-bill demand:

+ domestic (corps, pensions, insurance, HFs, banks)

+ foreign (other central banks or foreign entities)

+ central bank (QE)

+ governments directly (without CB intervention)

+ domestic (corps, pensions, insurance, HFs, banks)

+ foreign (other central banks or foreign entities)

+ central bank (QE)

+ governments directly (without CB intervention)

10/ She breaks down when/where demand has dried up;

How modern monetary theory (“MMT”) has come into vogue (i.e. we could theoretically print *forever* with minimal inflation);

And why the Fed’s balance sheet will continue to swell and create inflation *risk* at best.

How modern monetary theory (“MMT”) has come into vogue (i.e. we could theoretically print *forever* with minimal inflation);

And why the Fed’s balance sheet will continue to swell and create inflation *risk* at best.

11/ We were already running out of Treasury buyers pre-COVID, and there haven’t been net new domestic or foreign buyers in years.

This dynamic could get worse with a weak recovery / second wave of shutdowns.

This dynamic could get worse with a weak recovery / second wave of shutdowns.

12/ Let’s go buyer by buyer to see what’s happening, and get a better sense of where we’re heading.

(Hint: it’s uncertain, but almost certainly negative.)

(Hint: it’s uncertain, but almost certainly negative.)

13/ 1. Domestic investors: The first set of sovereign debt buyers comes from domestic sources. The yield on U.S. Treasuries is considered the “risk-free” rate of return because the U.S. Government is more creditworthy than 99.99% of citizens and companies.

14/ Individuals, corporates, hedge funds, banks, insurers, pensions, etc. buy government debt when they are looking for “safe” returns. Their "hurdle rates” on private investments rise and fall with risk-free rates.

15/ These investors get nudged into riskier assets when Treasury yields fall.

Credit loosens because investors have lower standards, and will search more broadly for any yield above risk-free rates. (This is why all asset prices were rallying pre-COVID.)

Credit loosens because investors have lower standards, and will search more broadly for any yield above risk-free rates. (This is why all asset prices were rallying pre-COVID.)

16/ Governments "compete” with private borrowers, so domestic demand for Treasuries can "crowd out” more productive investments if there is too much issuance and too high a savings rate.

The result can be sluggish growth (e.g. Japan& #39;s "Lost Decade”.)

The result can be sluggish growth (e.g. Japan& #39;s "Lost Decade”.)

17/ No one likes to kill the easy money / bull market vibes, which is why the Fed does more easing than tightening. They stimulate growth in sideways markets, but never cool things off when the economy runs hot.

(And they’ll dispute this when you say it out loud.)

(And they’ll dispute this when you say it out loud.)

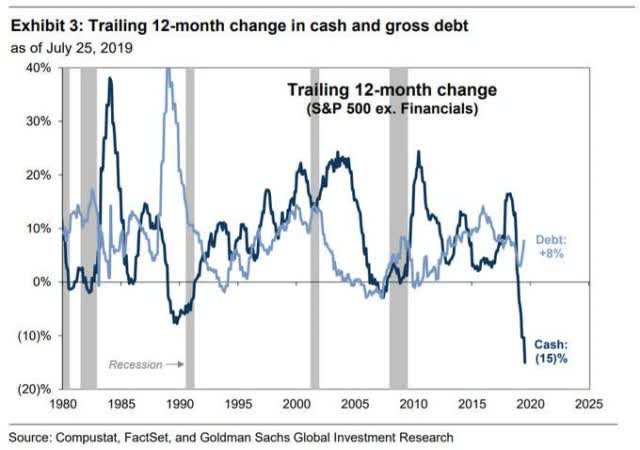

18/ Corporates absorbed Treasuries in 2018 following the tax cuts and foreign cash repatriation.

But that was a temporary demand driver, and they quickly swapped those assets for share buybacks.

(No demand today.)

But that was a temporary demand driver, and they quickly swapped those assets for share buybacks.

(No demand today.)

19/ As Lyn noted in another excellent piece, “insurance companies and pensions are slow-growing or in drawdown-mode in some cases.”

(Again, no demand today.) https://seekingalpha.com/article/4320078-curious-case-of-qe">https://seekingalpha.com/article/4...

(Again, no demand today.) https://seekingalpha.com/article/4320078-curious-case-of-qe">https://seekingalpha.com/article/4...

20 / The Repo Crisis last September (see Lyn& #39;s previous link in tweet above) showed how hedge funds and banks ran out of capacity for new Treasury auctions.

Banks had *already* accumulated record levels of federal debt and depleted their cash balances.

(Yep, no demand today.)

Banks had *already* accumulated record levels of federal debt and depleted their cash balances.

(Yep, no demand today.)

21/ 2. Foreign investors: Foreign sources of Treasury demand have also been gone for years.

Due to the strong dollar, net new demand for Treasuries has been basically non-existent since 2014. In fact, net foreign holdings of debt has declined since then.

(Again, no demand!)

Due to the strong dollar, net new demand for Treasuries has been basically non-existent since 2014. In fact, net foreign holdings of debt has declined since then.

(Again, no demand!)

22/ For most governments, that’s a problem.

Debt-fueled spending is a drug during boom times, but when the tide turns, investors get skittish, and the addict is screwed.

Debt issuances command higher yields when perceived creditworthiness declines.

Debt-fueled spending is a drug during boom times, but when the tide turns, investors get skittish, and the addict is screwed.

Debt issuances command higher yields when perceived creditworthiness declines.

23/ That usually either leads to:

a) vicious cycles where you need to implement painful austerity measures (e.g. Greece in 2012...tax hikes, spending cuts, crimped growth) to get creditworthy,

OR

b) devaluation of the currency by printing money from the central bank.

a) vicious cycles where you need to implement painful austerity measures (e.g. Greece in 2012...tax hikes, spending cuts, crimped growth) to get creditworthy,

OR

b) devaluation of the currency by printing money from the central bank.

24/ We’re lucky!

The U.S. has the global reserve currency (facilitates most international contracts).

And in recent years, demand for dollars has surged because our monetary policy has been *less bad* than other countries (e.g. negative rates in the Euro zone).

The U.S. has the global reserve currency (facilitates most international contracts).

And in recent years, demand for dollars has surged because our monetary policy has been *less bad* than other countries (e.g. negative rates in the Euro zone).

25/ So despite no non-Fed net buyers of Treasuries, we& #39;ve had some wiggle room.

The Fed has basically sucked up all new Treasury issuance since September, but people put up with our shit because they want MOAR dollars.

Still, there are signs we’re near the limit.

The Fed has basically sucked up all new Treasury issuance since September, but people put up with our shit because they want MOAR dollars.

Still, there are signs we’re near the limit.

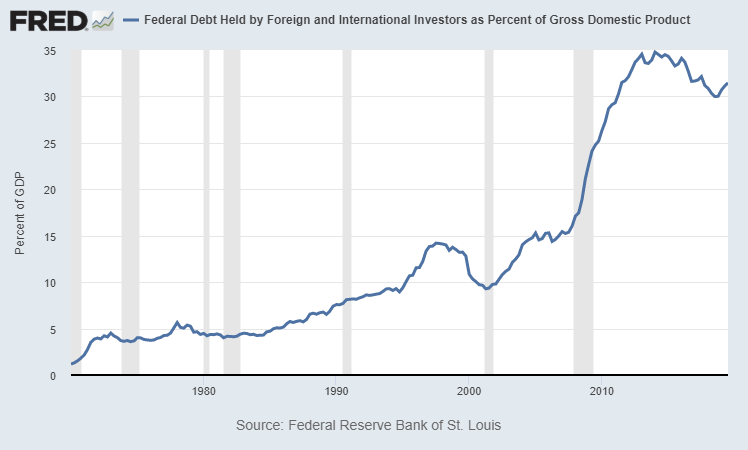

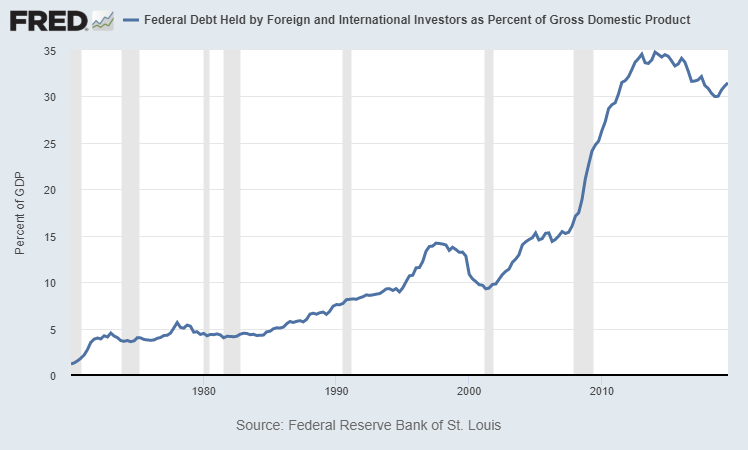

26/ On the debt issuance side, here’s (again) the U.S. debt held by foreign investors as a percentage of U.S. GDP:

1980: 5%

2000: 10%

2020: 30%+ and ripping!

This is why people quip “The dollar is our leading export.”

1980: 5%

2000: 10%

2020: 30%+ and ripping!

This is why people quip “The dollar is our leading export.”

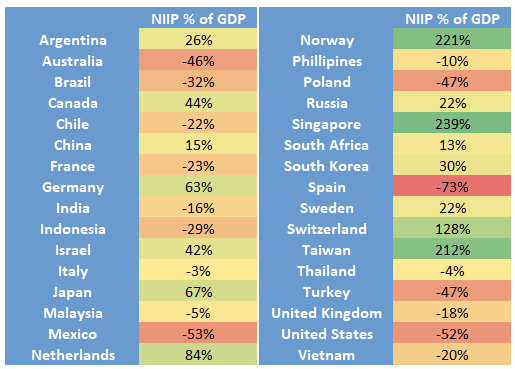

27/ Or look at this!

Our Net International Investment Position (net foreign ownership of our debt) now stands at -50% of GDP vs. -10% in 2008!

We’re likely at or near our NIIP limit. In good company with Mexico, Spain, and Turkey for “worst” global NIIP.

Our Net International Investment Position (net foreign ownership of our debt) now stands at -50% of GDP vs. -10% in 2008!

We’re likely at or near our NIIP limit. In good company with Mexico, Spain, and Turkey for “worst” global NIIP.

28/ This ratio can’t continue to decline on an accelerating basis forever. And it would also be painful to reverse.

So at best, NIIP flattens out, and we have one fewer arrow in our debt-fueled quiver. That’s indeed what’s happened since 2014.

So at best, NIIP flattens out, and we have one fewer arrow in our debt-fueled quiver. That’s indeed what’s happened since 2014.

29/ Remember, this all pre-dates COVID.

Now that COVID’s here, and there’s no corporate, bank, insurance, pension, or foreign demand, we are 100% reliant on the Fed from here on out.

All hail QE, the Fed, and King Jerome!

Now that COVID’s here, and there’s no corporate, bank, insurance, pension, or foreign demand, we are 100% reliant on the Fed from here on out.

All hail QE, the Fed, and King Jerome!

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter