I study early German scholars of Greek warfare.

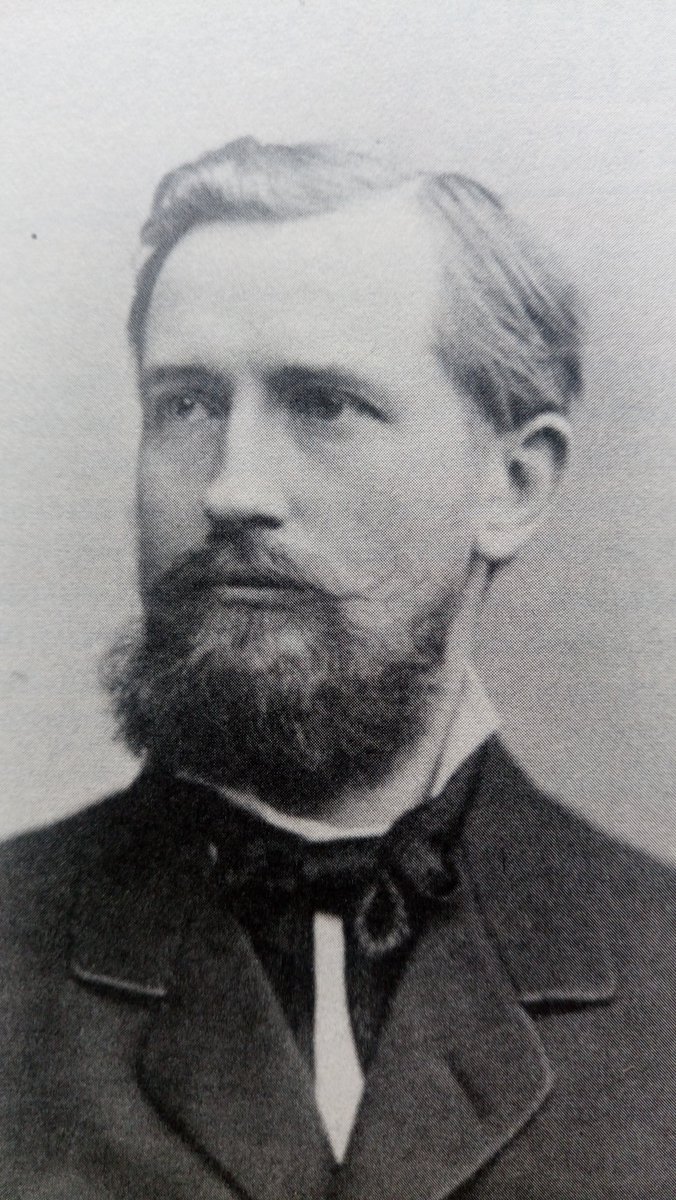

One of them rubbed shoulders with the Hohenzollerns, made an enemy of the entire General Staff, and is seen as the sole founder of academic military history.

Oh yes, it& #39;s Hans Delbrück, who died #OTD in 1929.

Let& #39;s go. 1/

One of them rubbed shoulders with the Hohenzollerns, made an enemy of the entire General Staff, and is seen as the sole founder of academic military history.

Oh yes, it& #39;s Hans Delbrück, who died #OTD in 1929.

Let& #39;s go. 1/

You can get the short of it from the way modern historians describe him. Delbrück, "who loved controversy" (Craig). Delbrück, "for whom history was always the continuation of war by other means" (Rauff).

He& #39;ll fite u.

2/

He& #39;ll fite u.

2/

By the way, if you feel like you& #39;ve heard the name before, it& #39;s probably because of @MelBrooks& #39; Young Frankenstein (1974). Delbrück& #39;s brain was the one intended for the monster.

Scientist yes. Saint, not so much. 3/

Scientist yes. Saint, not so much. 3/

How do you survive as a Prussian with such a penchant for making enemies? Well, privilege helps. The Delbrücks were a well-established family of lawyers, theologians and officials. Several of his cousins were secretaries of state. His uncle owned a bank. 4/

Delbrück was 21 when the Franco-Prussian War broke out. He describes how the French shot his unit to shreds in the bloodbath of Gravelotte-St Privat. In the gruelling siege of Metz, he contracted typhus and was discharged. 5/

He stayed on as a reservist and continued his studies in history. In 1873 he graduated under Heinrich von Sybel. His was the first thesis written in German to be submitted at the Philosophy faculty at Bonn. Germany was changing quickly. 6/

What next for Hans Delbrück? His connections help him to arrange a starter job. Nothing special, just tutoring this little local kid called Prince Waldemar of Prussia, son of the future king Frederick IV. 7/

Delbrück loves life at court. He has access to famous generals and their records. He works on his first big work, a biography of Gneisenau.

But tragedy strikes. Waldemar dies in 1879, aged 11, of diphtheria.

Delbrück already knows what he wants to do next. 8/

But tragedy strikes. Waldemar dies in 1879, aged 11, of diphtheria.

Delbrück already knows what he wants to do next. 8/

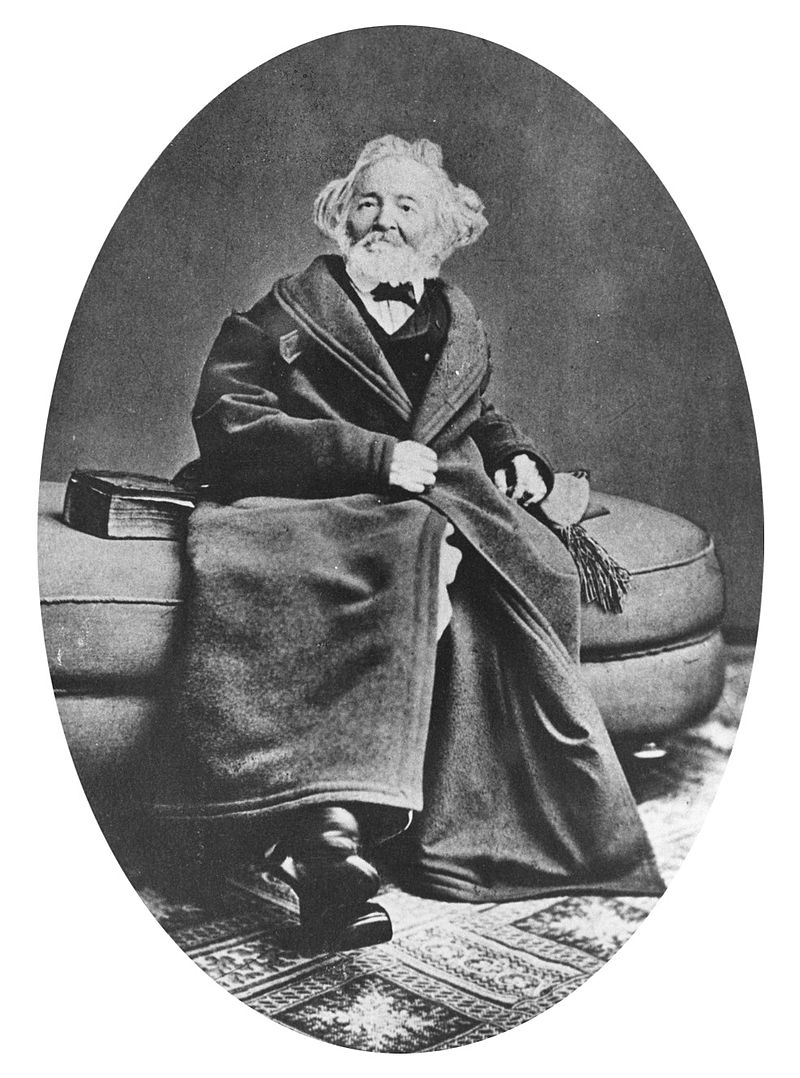

Back in 1874, Delbrück goes to the library of his reserve regiment and reads a book. This book inspires the entire rest of his career. It is called History of the Infantry.

It was written in 1857 by Wilhelm Rüstow (OH HELLO THERE.) 9/ https://twitter.com/Roelkonijn/status/1254078343110164482">https://twitter.com/Roelkonij...

It was written in 1857 by Wilhelm Rüstow (OH HELLO THERE.) 9/ https://twitter.com/Roelkonijn/status/1254078343110164482">https://twitter.com/Roelkonij...

Rüstow& #39;s work teaches Delbrück a life-changing lesson, which is this: Military History. It is a thing you can do. 10/

\Hans Delbrück has entered the chat.

HANS DELBRÜCK: Hey guys, question. Military history: is it a thing you can do?

GERMAN UNIVERSITIES: No.

THE GREAT GENERAL STAFF: Fuck no.

11/

HANS DELBRÜCK: Hey guys, question. Military history: is it a thing you can do?

GERMAN UNIVERSITIES: No.

THE GREAT GENERAL STAFF: Fuck no.

11/

What the hell, I hear you ask. What& #39;s the Great General Staff got to do with anything?

In 19th century Germany, military history was military science. It was a soldier& #39;s business. They did that stuff.

They had a research centre for it and everything. 12/

In 19th century Germany, military history was military science. It was a soldier& #39;s business. They did that stuff.

They had a research centre for it and everything. 12/

Wouldn& #39;t universities, you know, dispute that claim?

Hell no. That was not a battle of status they were gonna win. They left military history to soldiers.

When Delbrück tried to get appointed as a miltiary historian, Leopold Ranke told him to piss off. 13/

Hell no. That was not a battle of status they were gonna win. They left military history to soldiers.

When Delbrück tried to get appointed as a miltiary historian, Leopold Ranke told him to piss off. 13/

How did Delbrück respond to that? Have a guess.

14/

14/

But what exactly did he want to do? Well, in 1879 he fielded a detailed critique of the official army interpretation of the strategy of Frederick the Great.

National Prussian hero, Frederick the Great.

Delbrück, no.

15/

National Prussian hero, Frederick the Great.

Delbrück, no.

15/

This was "historical high treason" (Rauff). This was "sacrilege" (Deist). The entire Great General Staff lost its shit. Civil society lost its shit on their behalf. Questions were asked in Parliament (seriously). 16/

I& #39;m sure I don& #39;t need to spell out how Delbrück responded to literally everyone inside and outside his profession telling him to knock it off with the treason.

17/

17/

Reading about this you just hope that there& #39;s a point where he will chill.

He did not chill.

In 1887 he published "The Persian Wars and the Burgundian Wars" to let ancient historians know they were wrong about everything too. 18/

He did not chill.

In 1887 he published "The Persian Wars and the Burgundian Wars" to let ancient historians know they were wrong about everything too. 18/

In 1890 he published his comparative study of the strategies of Perikles and Frederick. He thought it would be funny to include a little parody to show how dumb Frederick would have to be to choose the strategy Delbrück& #39;s opponents suggested.

DUDE. MY DUDE.

19/

DUDE. MY DUDE.

19/

He insists that military history should be bigger than the way the army does it: that it shouldn& #39;t just be about battles, but include the social, political and economic structures that make war possible.

The army finds this very funny. The university thinks he is nuts. 20/

The army finds this very funny. The university thinks he is nuts. 20/

In case you& #39;re wondering if fighting the entire university and army establishment would be enough for him. No. No it was not. He also served as a representative to the Prussian and German Parliament (1882-1890). He also edited the monthly Preußisiche Jahrbücher. 21/

In the meantime he got married to Lina Thiersch and they had 7 kids. The one with the clearly cursed name Waldemar died in WW1. But 2 of them would eventually work in the resistance against Hitler. One moved to America and won a Nobel Prize in biochemistry. 22/

Meanwhile daddy Delbrück - despite his best efforts - finally gets tenure in Berlin in 1895.

As a general historian, not a military historian.

He will never get to call himself a military historian, nor will any of his 75 doctoral students. 23/

As a general historian, not a military historian.

He will never get to call himself a military historian, nor will any of his 75 doctoral students. 23/

All his colleagues resent his appointment. They accuse him of abusing royal favour.

Philosopher Wilhelm Dilthey calls it "the ruin of the study of history in Berlin for a generation".

24/

Philosopher Wilhelm Dilthey calls it "the ruin of the study of history in Berlin for a generation".

24/

His most famous work starts to appear from 1900: The 4-volume History of the Art of War in the Framework of Political History. It& #39;s big. It will eventually be translated into Russian and English.

Delbrück gets read. By notable people. 25/

Delbrück gets read. By notable people. 25/

He gets read by this little known general called Alfred Graf von Schlieffen, former Chief of the Great General Staff.

Delbrück& #39;s account of the battle of Cannae (216 BC) directly inspires the Schlieffen Plan.

Oh shit.

26/

Delbrück& #39;s account of the battle of Cannae (216 BC) directly inspires the Schlieffen Plan.

Oh shit.

26/

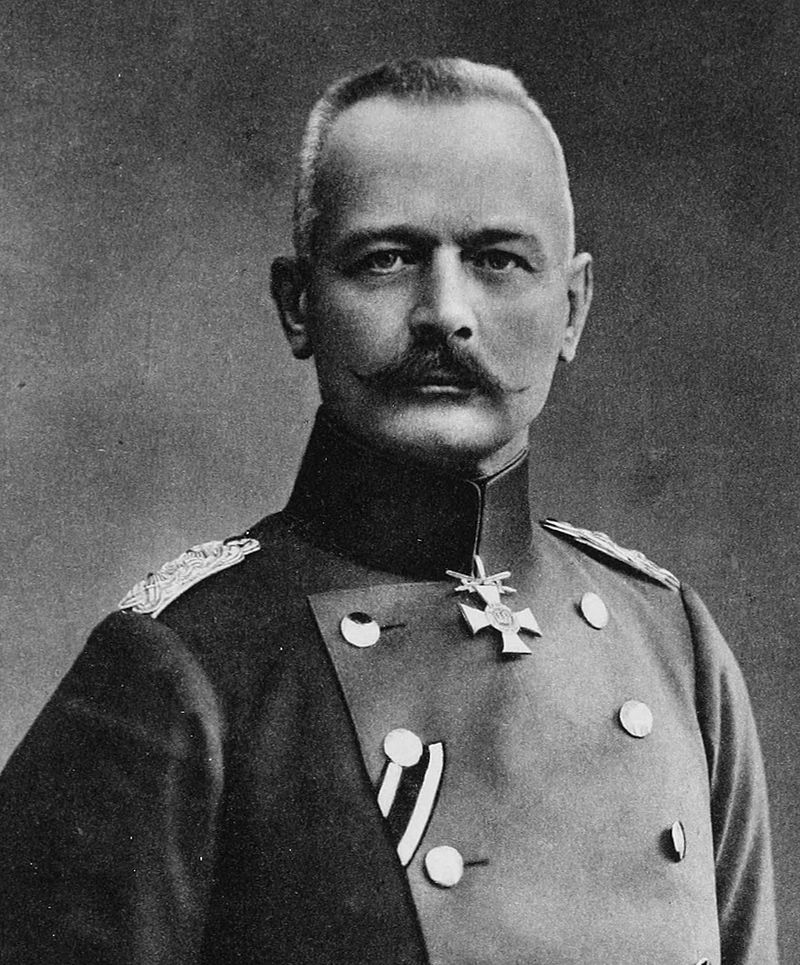

Delbrück did not believe in quick victory in WW1. The Entente simply had more people. He favoured a strategy of attrition and negotiation.

He tells Erich von Falkenhayn about this in a private conversation.

Soon after, Falkenhayn starts the Battle of Verdun.

Oh. Shit.

27/

He tells Erich von Falkenhayn about this in a private conversation.

Soon after, Falkenhayn starts the Battle of Verdun.

Oh. Shit.

27/

It& #39;s not certain how much influence he really had, though. He always campaigned for a political solution to the war, and was always ignored. Germany was obsessed with total victory. 28/

He constantly tries to get himself heard. He is present, along with Max Weber and others, at Versailles (not shown).

He is head of the advisory council to the Reichsarchiv that is to write the history of the war. 29/

He is head of the advisory council to the Reichsarchiv that is to write the history of the war. 29/

He insists that they should write a whole history. One that includes soc, econ and cultural factors.

The officers outvote him. "The war was fought by the old army and so it will be written by the old army." 30/

The officers outvote him. "The war was fought by the old army and so it will be written by the old army." 30/

Delbrück lives on for another decade, but the postwar episode sums up his life. He tried to make military history a proper discipline, but he failed. No one in power wanted this. No one followed in his footsteps. 31/

But was it all for nothing?

He kept on engaging the Great General Staff, and they had to meet him, until "it was no longer possible to fall below the standards set by Delbrück" (Lange).

We stand on the shoulders of this stubborn giant. /fin

He kept on engaging the Great General Staff, and they had to meet him, until "it was no longer possible to fall below the standards set by Delbrück" (Lange).

We stand on the shoulders of this stubborn giant. /fin

Thaks for reading #twitterstorians!

The research behind this thread was funded by the @EU_H2020 research and innovation programme under Grant Agreement 793094

The research behind this thread was funded by the @EU_H2020 research and innovation programme under Grant Agreement 793094

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter