In the midst of all this insanity, I& #39;m going to start a thread on Līlāvatī of Poḷonnaruwa, one of the most fascinating figures in Lankan history (according to my mum at least). Because I need to remind myself why I came to the US for study, basically. #queenship #medievaltwitter

There& #39;s NOTHING substantial written on Līlāvatī in English scholarship. It& #39;s largely due to her relative absence from monastic chronicles like the Mahāvaṃsa; she& #39;s mentioned in just a few lines of verse. But those verses hint at some really fundamental issues of power & gender

Līlāvatī is first mentioned as the cousin and later wife of Parākramabahu I, one of the most important monarchs in 12th century Lanka. Here she& #39;s basically just an accessory to his claim to the throne, underlining his impeccable lineage. It gets more interesting after he dies!

PKB I& #39;s reign (1123–1186) is an unusually long and stable period. After his death there& #39;s a series of kings from various families and factions, none lasting particularly long. Eventually, a coup(?) puts Līlāvatī on the throne in 1197.

She& #39;s deposed in 1200, but then reinstated by another coup not once but twice, ruling again from 1209-1210 and 1211-1212. Something& #39;s going on here - why was this one woman so repeatedly placed on and off the throne?

We might see the noble widow of a powerful former king as the ideal figurehead for 3 generals with military strength but no real standing to claim the throne themselves. But female monarchs were extremely rare; was she really the strongest candidate even to be a puppet? 3 times?

There& #39;s a lot of evidence to suggest that some were uncomfortable with a female ruler, even if she was only nominally a ruler (which I& #39;m skeptical about). The passing references in the Mahāvaṃsa suggest that the monks weren& #39;t exactly invested in the merits of her reigns.

And the wording in these references is interesting too: while male monarchs "became king" or even just "carried out the kingship," most Mahāvaṃsa verses just tell us Līlāvatī was "caused to stand in the kingdom" - a rather oblique phrase.

I argued in an older thread that this partly a grammatical issue: "king" is masculine in Pali, and it wouldn& #39;t make sense to say "she[f] became king[m]." But grammar is never neutral; the grammatical masculinity of "king" reflects the masculinity of kingship

And this is reflected in her inscriptions (over which she likely had more control than the MV, written after her death). Here she& #39;s never "king," but she& #39;s also not any of the titles we usually translate "queen", except when describing her relationship to her deceased husband PKB

In other words: "king" was understood to be male, but "queen" (bisova, mahesi, räjini) was understood to be a subordinate consort, not a regnant female monarch. Neither term described Līlāvatī.

There IS one fascinating inscription in which she is described as "raja pämiṇä." Depending on how you translate this, it could be either "attained sovereignty" OR "became king" (the masculine term)! I *suspect* that this ambiguity is somewhat intentional on Līlāvatī& #39;s part

My instinct is that she& #39;s using some of the ambiguities of Sinhala grammar (as opposed to Pali or Sanskrit) to subversively claim kingship even while it& #39;s grammatically - and therefore symbolically - denied to her. The inscriptions hint at this; we get even more from her coins

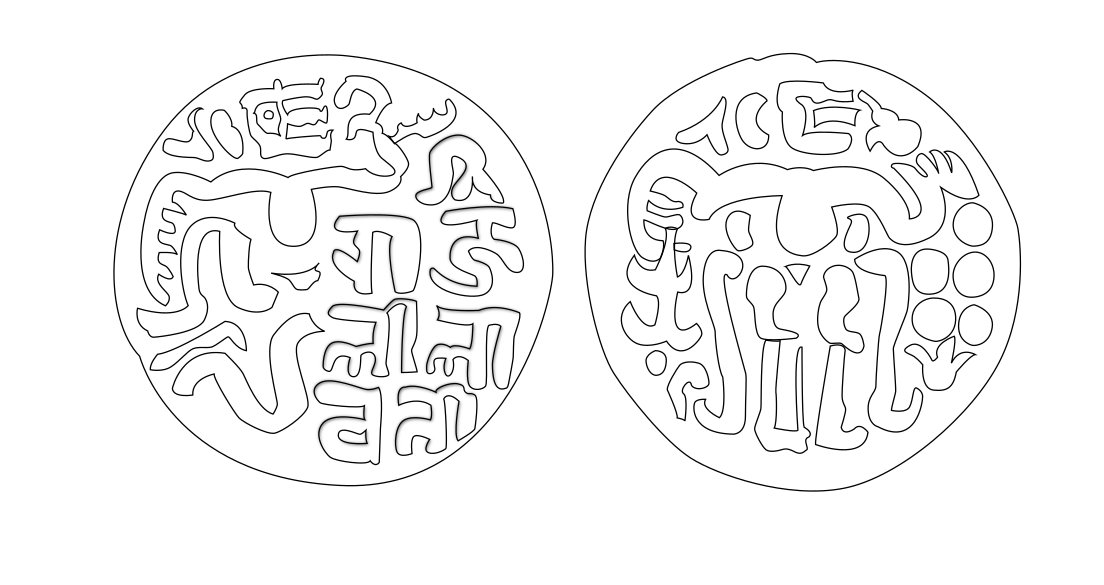

The name on the coins (faintly highlighted left) reads "Śri Raja Līlāvatī" - "Auspicious KING Līlāvatī," the masculine title preceding the feminine personal name (note long -ī ending). There& #39;s clearly room for a feminine "rajā"; this wording is deliberate.

What& #39;s super interesting here is that, unlike her inscriptions, the script on the coins isn& #39;t Sinhala; it& #39;s an early Devanagari. These were clearly meant to circulate beyond Lanka. 12th C soft power at work?

A lot of numismatic theory assumes that coins disseminated the Royal presence domestically. But since the script isn& #39;t Sinhala, and the abstract image isn& #39;t unique to L, I don& #39;t think that& #39;s what& #39;s going on here.

L is clearly playing to multiple audiences, across multiple media, and making what I see as a subversive if subtle claim to otherwise exclusively masculine kingship.

Her grip on power was tenuous at best; she may really have been little more than a thrice deposed puppet. But even if she lost the game, we can learn so much about its rules from how she played it!

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter