[THREAD: THE WALL STREET JOURNAL]

1/70

Long before there was an America or an England, Roman ships were carrying wine and gold to India and returning with spices, silk, and exotic animals. These trades were extremely profitable. And risky. Because bad weather and pirates.

1/70

Long before there was an America or an England, Roman ships were carrying wine and gold to India and returning with spices, silk, and exotic animals. These trades were extremely profitable. And risky. Because bad weather and pirates.

2/70

To hedge these risks, merchants would seek investments from wealthy moneylenders. If the ship returned, everyone made a killing. If not, it was lost investment. With enough money, you could thus buy into a voyage of your choice and make a fortune. This was great!

To hedge these risks, merchants would seek investments from wealthy moneylenders. If the ship returned, everyone made a killing. If not, it was lost investment. With enough money, you could thus buy into a voyage of your choice and make a fortune. This was great!

3/70

With time, the system matured and instead of investing a fortune in a single ship, a very risky proposition, you could invest small amounts in multiple ships and each ship could seek piecemeal investments from multiple investors like you. The "hedge fund" was born.

With time, the system matured and instead of investing a fortune in a single ship, a very risky proposition, you could invest small amounts in multiple ships and each ship could seek piecemeal investments from multiple investors like you. The "hedge fund" was born.

4/70

Centuries before Shakespeare, the merchants of Venice were already running a mighty evolved form of what could be called the world& #39;s first banking system. In time, the prototype was copied by other economic powerhouses including the Netherlands.

Centuries before Shakespeare, the merchants of Venice were already running a mighty evolved form of what could be called the world& #39;s first banking system. In time, the prototype was copied by other economic powerhouses including the Netherlands.

5/70

This led to the first maritime royal charter of Europe, a company granted special rights to raise capital to explore distant lands, govern them, exploit them for resources, and trade with them. A trading company, if you will. The Dutch East India Company was born.

This led to the first maritime royal charter of Europe, a company granted special rights to raise capital to explore distant lands, govern them, exploit them for resources, and trade with them. A trading company, if you will. The Dutch East India Company was born.

6/70

This was followed by a frenzy of other trading companies on similar lines including Dutch West India Company, British East India Company, London Company, Plymouth Company, etc. This was the 1600s. America had been discovered and settled by then.

This was followed by a frenzy of other trading companies on similar lines including Dutch West India Company, British East India Company, London Company, Plymouth Company, etc. This was the 1600s. America had been discovered and settled by then.

7/70

Sometime in 1626, the Dutch West India Company appointed a new director for the New World. His name, Peter Minuit. Minuit arrived in what was then "New Netherland" on May 4, 1626. He was a Walloon from Belgium. Walloons are a Romance people from Belgium.

Sometime in 1626, the Dutch West India Company appointed a new director for the New World. His name, Peter Minuit. Minuit arrived in what was then "New Netherland" on May 4, 1626. He was a Walloon from Belgium. Walloons are a Romance people from Belgium.

8/70

Long, long ago when the Germanic tribes from the north first came in contact with the peoples of the Western Roman Empire they identified the latter as Walhaz, a Proto-Germanic name for Romance and Celtic speakers. The latter, of course, called them the Barbarians.

Long, long ago when the Germanic tribes from the north first came in contact with the peoples of the Western Roman Empire they identified the latter as Walhaz, a Proto-Germanic name for Romance and Celtic speakers. The latter, of course, called them the Barbarians.

9/70

From Walhaz we get names like Wales, Cornwall, Wallachia, Wallonia, Vaals, Wallace, and even the good old walnut. Of these, Wallonia is the French-speaking half of Belgium; its people, the Walloons. One of these Walloons was Peter Minuit of the Dutch West India Co.

From Walhaz we get names like Wales, Cornwall, Wallachia, Wallonia, Vaals, Wallace, and even the good old walnut. Of these, Wallonia is the French-speaking half of Belgium; its people, the Walloons. One of these Walloons was Peter Minuit of the Dutch West India Co.

10/70

Soon upon arrival, Minuit made a crucial purchase. A swampy island with a great natural harbor right off the coast of New Netherland, then inhabited by the Lenape Indians. The natives called it Manhattan. Minuit bought it for the equivalent of $1,143 in today& #39;s money.

Soon upon arrival, Minuit made a crucial purchase. A swampy island with a great natural harbor right off the coast of New Netherland, then inhabited by the Lenape Indians. The natives called it Manhattan. Minuit bought it for the equivalent of $1,143 in today& #39;s money.

11/70

The Dutch West India Co. named it New Amsterdam. The first thing you ought to do right after a purchase like that is secure the property. Especially if the property happens to be in a place like New Netherland. So Peter Minuit built a 1,340-foot wall. A wooden palisade.

The Dutch West India Co. named it New Amsterdam. The first thing you ought to do right after a purchase like that is secure the property. Especially if the property happens to be in a place like New Netherland. So Peter Minuit built a 1,340-foot wall. A wooden palisade.

12/70

Built with freshly-introduced slave labor, this wall effectively cut off Minuit& #39;s New Amsterdam from what& #39;s now lower East Side. This offered protection from the natives and also kept the livestock from straying into the wild north. Only one problem though — the English.

Built with freshly-introduced slave labor, this wall effectively cut off Minuit& #39;s New Amsterdam from what& #39;s now lower East Side. This offered protection from the natives and also kept the livestock from straying into the wild north. Only one problem though — the English.

13/70

Right alongside this wooden palisade ran a street. Minuit named it de Waalstraat (lit. Walloon Street). One theory attributes the name to Minuit& #39;s Walloon origins, another to the literal wall. Either way, the wall stood tall for decades and witnessed much.

Right alongside this wooden palisade ran a street. Minuit named it de Waalstraat (lit. Walloon Street). One theory attributes the name to Minuit& #39;s Walloon origins, another to the literal wall. Either way, the wall stood tall for decades and witnessed much.

14/70

By 1653, the colony of New Netherland had a new governor-general, their last, in Peter Stuyvesant. He had the palisade further fortified to a height of 12 feet, coast to coast (at that time). Now although the north had been secured, the south remained vulnerable.

By 1653, the colony of New Netherland had a new governor-general, their last, in Peter Stuyvesant. He had the palisade further fortified to a height of 12 feet, coast to coast (at that time). Now although the north had been secured, the south remained vulnerable.

15/70

The British and the Dutch weren& #39;t very friendly back then; too many conflicting business interests. As bulk of European trade routes were maritime, harbors were particular bones of contention. So acquiring as many of those as possible was an imperial imperative.

The British and the Dutch weren& #39;t very friendly back then; too many conflicting business interests. As bulk of European trade routes were maritime, harbors were particular bones of contention. So acquiring as many of those as possible was an imperial imperative.

16/70

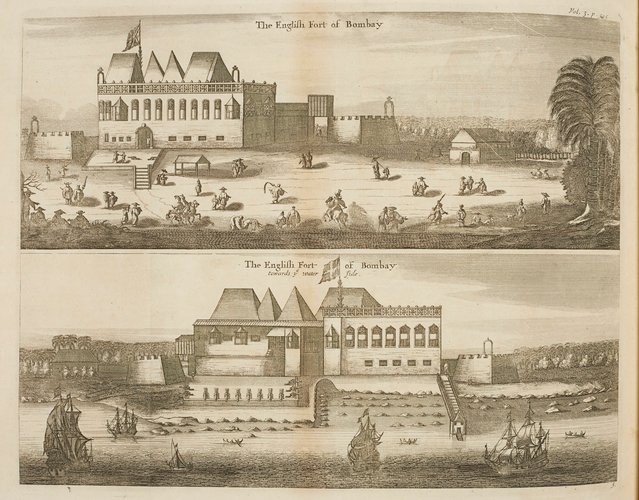

To that effect, King Charles II of England married Catherine of Braganza in 1661 and received the Seven islands of Bombay in dowry. This offered Britain a big advantage over the Dutch who at the time held Bengal, the richest part of the subcontinent.

To that effect, King Charles II of England married Catherine of Braganza in 1661 and received the Seven islands of Bombay in dowry. This offered Britain a big advantage over the Dutch who at the time held Bengal, the richest part of the subcontinent.

17/70

Coming back to Manhattan, a change of ownership took place in 1664. On Aug 27, 4 English frigates sailed into the harbor and demanded New Netherland& #39;s surrender. By 1665, the territory had gone to the Duke of York, brother of King Charles II. He renamed the place New York.

Coming back to Manhattan, a change of ownership took place in 1664. On Aug 27, 4 English frigates sailed into the harbor and demanded New Netherland& #39;s surrender. By 1665, the territory had gone to the Duke of York, brother of King Charles II. He renamed the place New York.

18/70

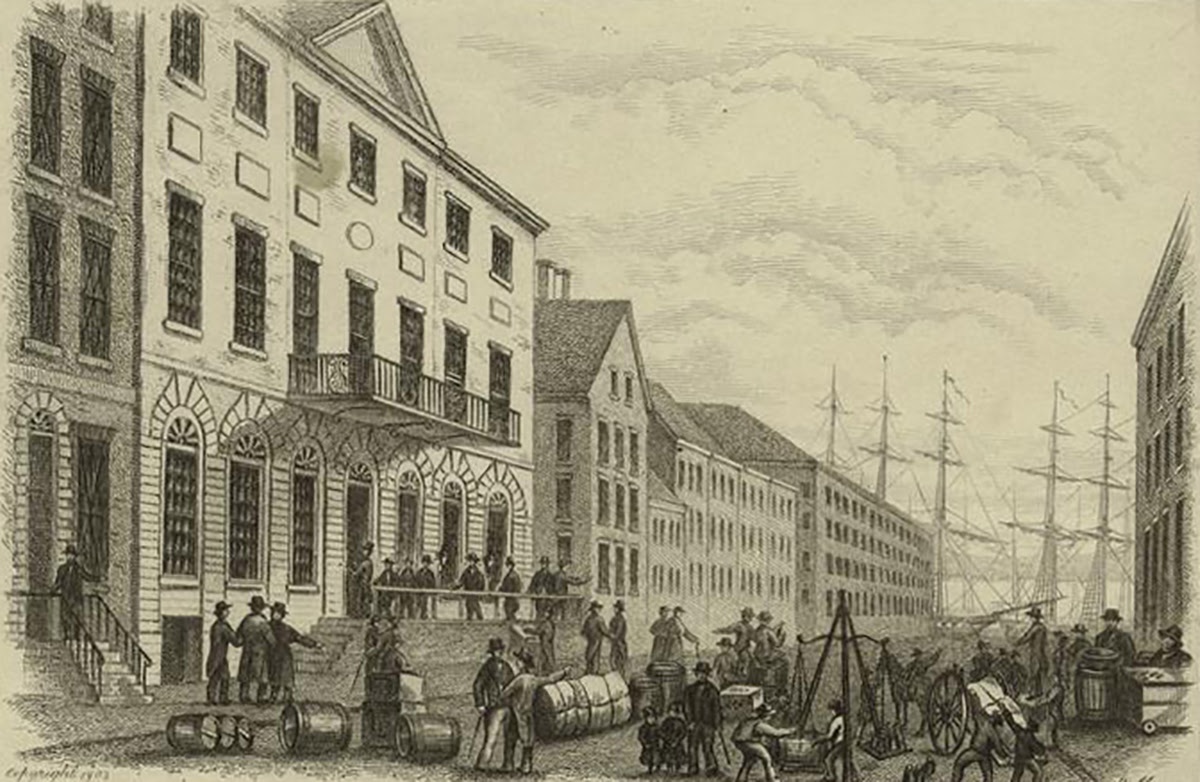

Once New Amsterdam became New York, de Waalstraat also became Wall Street. The street had by then become a rendezvous for pirates and commodity traders. Two kinds of traders existed — the auctioneers who set prices through competitive bidding, and the dealers who traded.

Once New Amsterdam became New York, de Waalstraat also became Wall Street. The street had by then become a rendezvous for pirates and commodity traders. Two kinds of traders existed — the auctioneers who set prices through competitive bidding, and the dealers who traded.

19/70

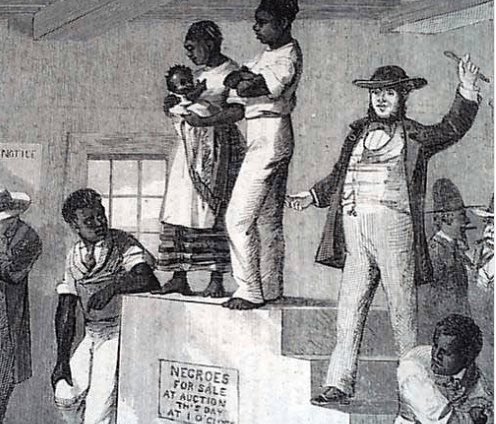

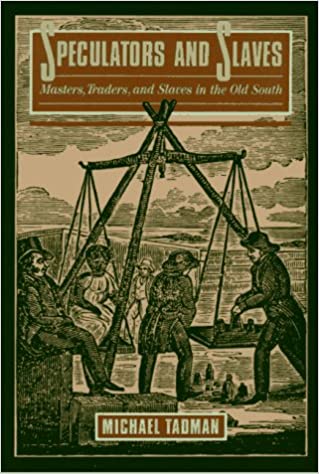

With time, the street also became a trading center for slaves where owners could rent theirs out by the day or week. Much money was made as the city& #39;s first wharf was built at the eastern end of the street on East River in 1694. The area soon grew into a mercantile center.

With time, the street also became a trading center for slaves where owners could rent theirs out by the day or week. Much money was made as the city& #39;s first wharf was built at the eastern end of the street on East River in 1694. The area soon grew into a mercantile center.

20/70

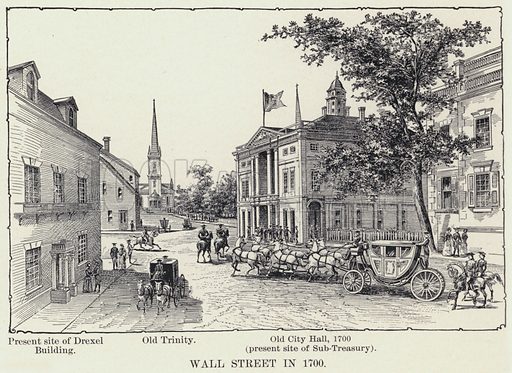

Along with slaves, grains too became a heavily traded commodity here. Thus it came to be dubbed the city& #39;s "meal market." The wall itself came down in 1699 as NY expanded further north but the name stuck. In 1700, the city got its first City Hall, on this very street.

Along with slaves, grains too became a heavily traded commodity here. Thus it came to be dubbed the city& #39;s "meal market." The wall itself came down in 1699 as NY expanded further north but the name stuck. In 1700, the city got its first City Hall, on this very street.

21/70

Besides the City Hall and the auction block for slavers, Wall Street was also host to the town pillory and city jail. Somewhere on the street was also an arena for an imported form of bullfight known as bear-baiting. This sport involved, as you guessed, two animals.

Besides the City Hall and the auction block for slavers, Wall Street was also host to the town pillory and city jail. Somewhere on the street was also an arena for an imported form of bullfight known as bear-baiting. This sport involved, as you guessed, two animals.

22/70

In bear-baiting, a grizzly was typically tied to a post as a bait for a charging bull. The bull could win by driving "up" with its horns; the bear could survive this by wrestling the bull "down" and breaking its neck. Although the sport no longer remains, its relics do.

In bear-baiting, a grizzly was typically tied to a post as a bait for a charging bull. The bull could win by driving "up" with its horns; the bear could survive this by wrestling the bull "down" and breaking its neck. Although the sport no longer remains, its relics do.

23/70

Throughout the early years of 1700s, though, America remained an agrarian economy. Whatever few joint-stock businesses existed were of the speculative kind. They speculated in land parcels. This was profitable given the heavy influx of homesteaders and farmers from Europe.

Throughout the early years of 1700s, though, America remained an agrarian economy. Whatever few joint-stock businesses existed were of the speculative kind. They speculated in land parcels. This was profitable given the heavy influx of homesteaders and farmers from Europe.

24/70

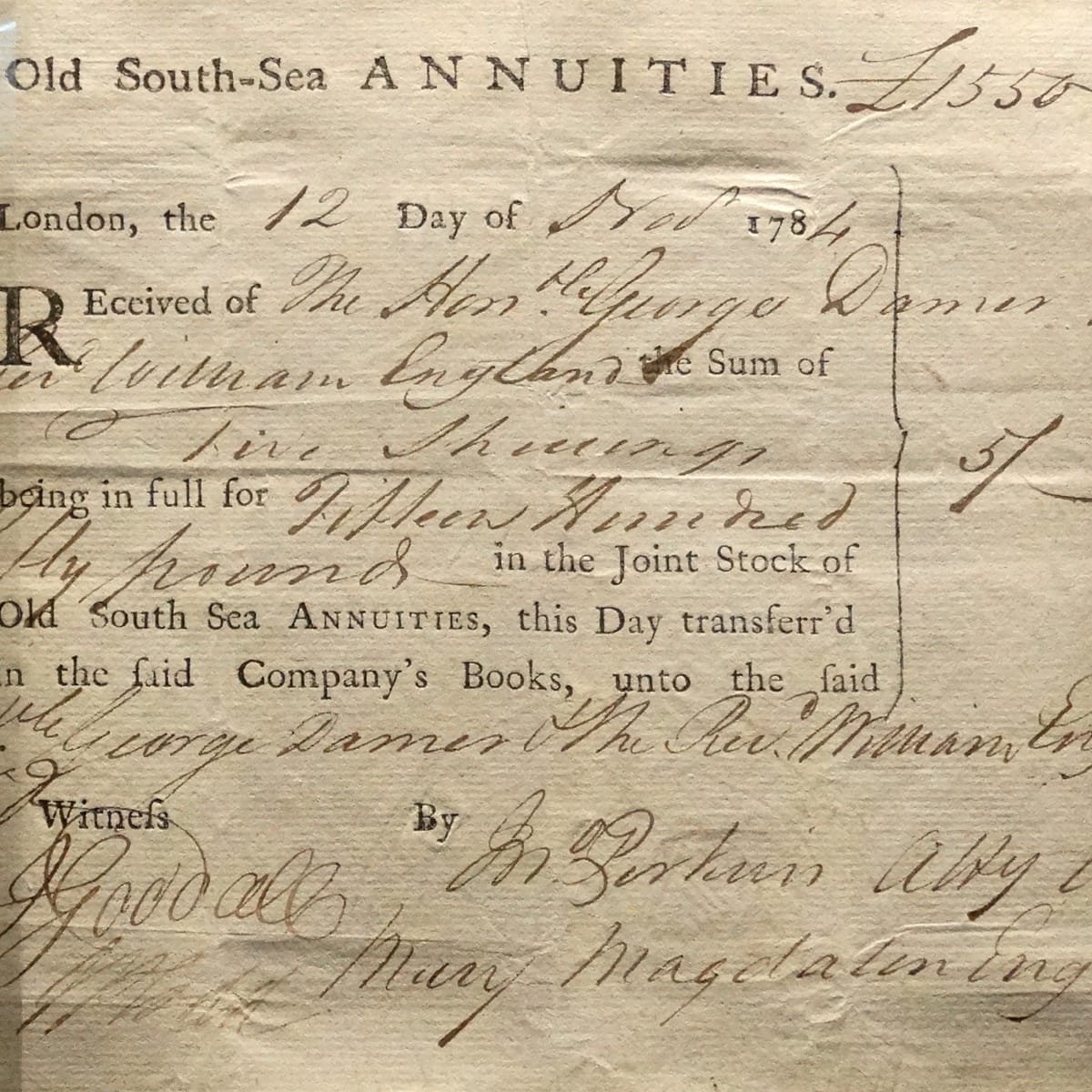

Some money was also made trading English bonds. Bonds are basically documents issued and sold by governments for a fixed sum with a promise of buyback at a later date with interest. Since they& #39;re issued by the govt., they& #39;re considered a safe investment for the buyer.

Some money was also made trading English bonds. Bonds are basically documents issued and sold by governments for a fixed sum with a promise of buyback at a later date with interest. Since they& #39;re issued by the govt., they& #39;re considered a safe investment for the buyer.

25/70

In turn, selling these bonds help the govt. raise capital for running its affairs. Early 1700s were a particularly tough time for the imperial governments including the British, thanks to the myriad wars they were engaged in. So bonds made for an easy fundraiser.

In turn, selling these bonds help the govt. raise capital for running its affairs. Early 1700s were a particularly tough time for the imperial governments including the British, thanks to the myriad wars they were engaged in. So bonds made for an easy fundraiser.

26/70

In New York, another market was emerging. The market of bond speculators. There were already land speculators who initially made a lot of money but then started losing as land prices tanked. One such loser was George Washington. Many of those then turned to English bonds.

In New York, another market was emerging. The market of bond speculators. There were already land speculators who initially made a lot of money but then started losing as land prices tanked. One such loser was George Washington. Many of those then turned to English bonds.

27/70

Bond speculation worked the same way as land speculation. You bet on whether the price of a particular bond would go up or down in a given period. If you guessed right, you make a killing. If not, you lost your shirt. Naturally, very few daredevils considered doing this.

Bond speculation worked the same way as land speculation. You bet on whether the price of a particular bond would go up or down in a given period. If you guessed right, you make a killing. If not, you lost your shirt. Naturally, very few daredevils considered doing this.

28/70

But NY wasn& #39;t the only center of action those days. There were 2 others — Boston and Philadelphia. In fact, Chestnut Street, Philly& #39;s business center, was a much busier and noisier market than Wall Street. Being further south, it attracted a lot of plantation speculators.

But NY wasn& #39;t the only center of action those days. There were 2 others — Boston and Philadelphia. In fact, Chestnut Street, Philly& #39;s business center, was a much busier and noisier market than Wall Street. Being further south, it attracted a lot of plantation speculators.

29/70

1754 saw Britain and France face-off in a series of conflicts collectively known as the French and Indian War (or the Seven Years& #39; War in Europe). Britain emerged victorious with the Treaty of Paris in 1763. This treaty had implications, both in America and in India.

1754 saw Britain and France face-off in a series of conflicts collectively known as the French and Indian War (or the Seven Years& #39; War in Europe). Britain emerged victorious with the Treaty of Paris in 1763. This treaty had implications, both in America and in India.

30/70

In America, Louisbourg went from Britain back to France. In India, France pledged to never disturb Britain& #39;s rule over Bengal. This sowed the seeds of resentment among the colonials because they didn& #39;t like the idea of losing Louisbourg after scoring it with their lives.

In America, Louisbourg went from Britain back to France. In India, France pledged to never disturb Britain& #39;s rule over Bengal. This sowed the seeds of resentment among the colonials because they didn& #39;t like the idea of losing Louisbourg after scoring it with their lives.

31/70

On the other side of the world, Robert Clive was back in India for a 3rd stint, this time as the first British Governor of the Bengal Presidency which, by the way, was all of North India including Pakistan. Along with Clive went a 22 year old Eton-educated William Duer.

On the other side of the world, Robert Clive was back in India for a 3rd stint, this time as the first British Governor of the Bengal Presidency which, by the way, was all of North India including Pakistan. Along with Clive went a 22 year old Eton-educated William Duer.

32/70

Duer was an Englishman born in money; his parents had plantations in the Caribbean. When Clive set sail for India, Duer sailed with him as his aide. This was quite the opportunity as much money was to be made in this strange land, Bengal being the epicenter of wealth.

Duer was an Englishman born in money; his parents had plantations in the Caribbean. When Clive set sail for India, Duer sailed with him as his aide. This was quite the opportunity as much money was to be made in this strange land, Bengal being the epicenter of wealth.

33/70

But climate ruined it for Duer who couldn& #39;t cope with the tropical heat and humidity and was soon packed home by his boss to prevent further illness. Later, Duer was invited to NY by trading partner and one of the Founding Fathers of America, Philip John Schuyler.

But climate ruined it for Duer who couldn& #39;t cope with the tropical heat and humidity and was soon packed home by his boss to prevent further illness. Later, Duer was invited to NY by trading partner and one of the Founding Fathers of America, Philip John Schuyler.

34/70

By the 1770s, Duer had purchased land parcels and set up a successful lumber business on the upper Hudson River near Albany. The resentment between the colonials and the British, meanwhile, grew worse...until a war broke out in 1775. The American War of Independence.

By the 1770s, Duer had purchased land parcels and set up a successful lumber business on the upper Hudson River near Albany. The resentment between the colonials and the British, meanwhile, grew worse...until a war broke out in 1775. The American War of Independence.

35/70

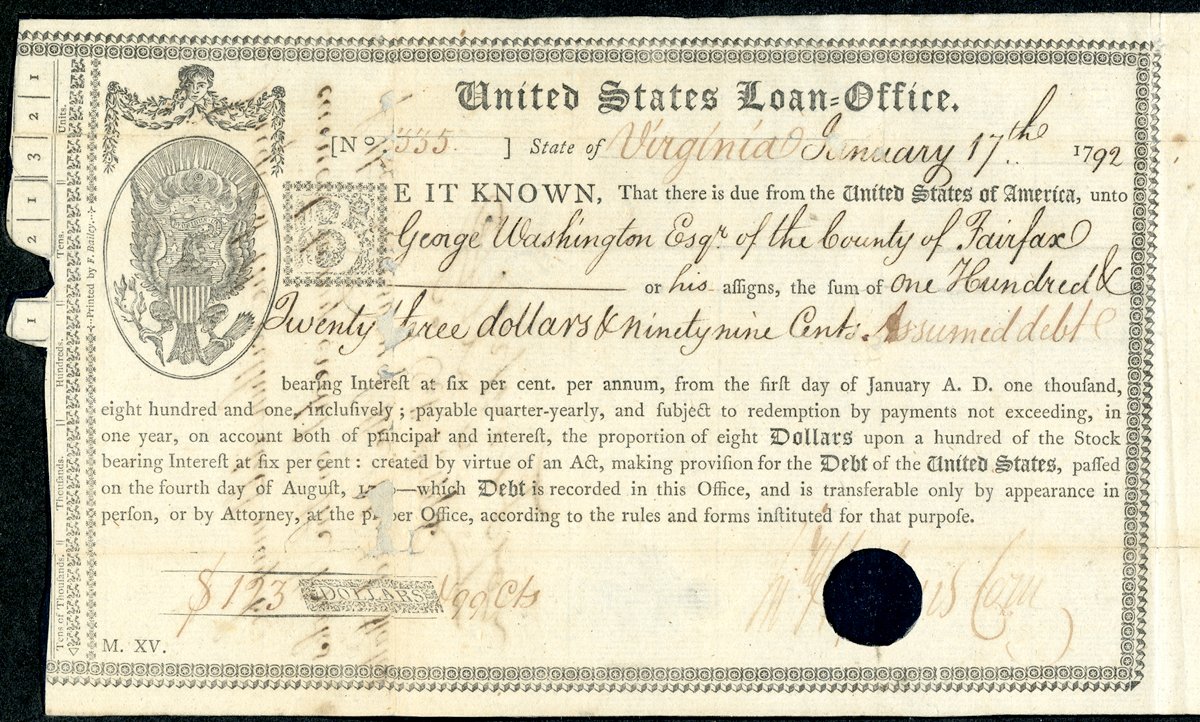

This war, also known as the American Revolution, gave birth to Confederacy Bonds. These were issued by the Continental Congress to raise funds for the war and their values rose and fell everyday with news of Washington& #39;s performance at the battlefields. Confused?

This war, also known as the American Revolution, gave birth to Confederacy Bonds. These were issued by the Continental Congress to raise funds for the war and their values rose and fell everyday with news of Washington& #39;s performance at the battlefields. Confused?

36/70

Bondholders were to be paid by the new government with interest; but the government had to come into being first. Every win Washington& #39;s men scored at the battlefields made this more likely, thus shooting up the price of those bonds. And vice versa.

Bondholders were to be paid by the new government with interest; but the government had to come into being first. Every win Washington& #39;s men scored at the battlefields made this more likely, thus shooting up the price of those bonds. And vice versa.

37/70

This triggered the New World& #39;s first speculative frenzy, its first bull run. To fund the war and make money doing it, Philadelphia traders floated a bank in 1781. Bank of North America. Several mergers down the line, it exists today as Bank of New York Mellon.

This triggered the New World& #39;s first speculative frenzy, its first bull run. To fund the war and make money doing it, Philadelphia traders floated a bank in 1781. Bank of North America. Several mergers down the line, it exists today as Bank of New York Mellon.

38/70

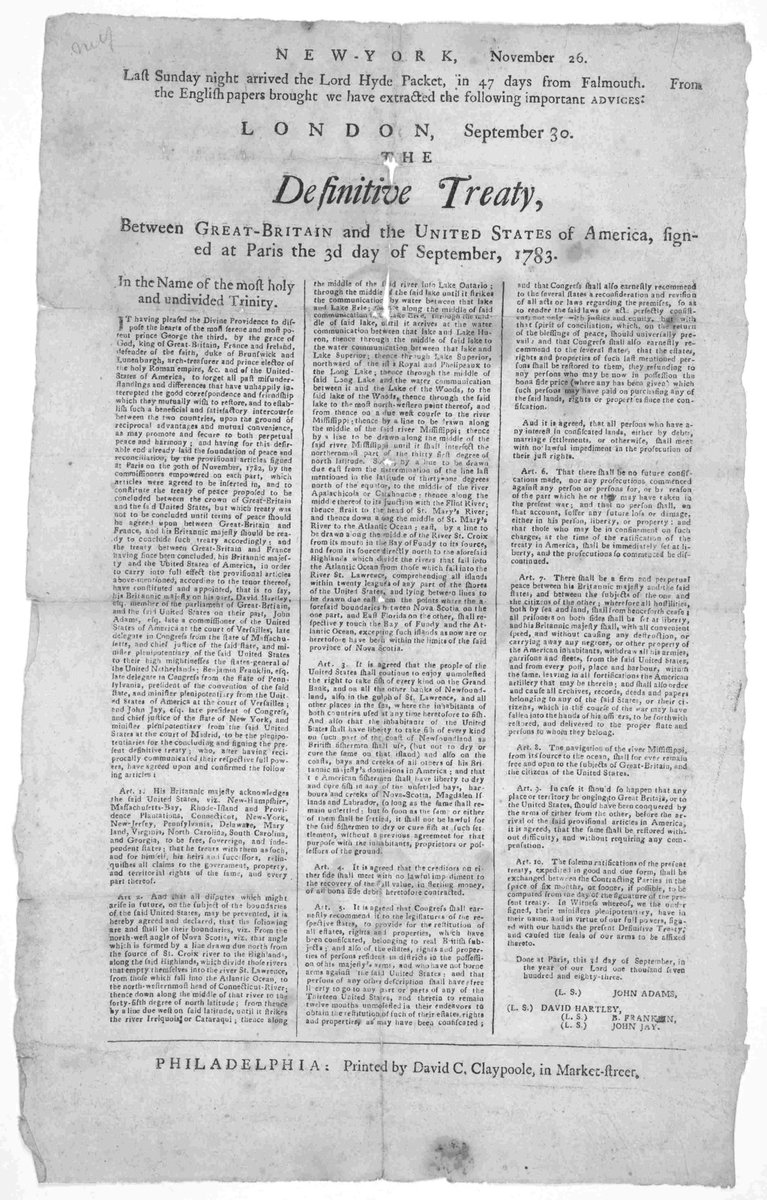

On Sep 3, 1783, the war ended and the US became a free country per the 15th Treaty of Paris. After the war, Duer entered the speculation business and made a lot of money, much of it manipulating the market. His unscrupulous means would return to haunt him years later.

On Sep 3, 1783, the war ended and the US became a free country per the 15th Treaty of Paris. After the war, Duer entered the speculation business and made a lot of money, much of it manipulating the market. His unscrupulous means would return to haunt him years later.

39/70

During these years of feeding frenzy, the 3 financial hubs were in a bitter contest over financial supremacy in the new nation. To counter Philly& #39;s banking gambit, Wall Street came up with Bank of New York in 1784. The bull run intensified. A crash was imminent.

During these years of feeding frenzy, the 3 financial hubs were in a bitter contest over financial supremacy in the new nation. To counter Philly& #39;s banking gambit, Wall Street came up with Bank of New York in 1784. The bull run intensified. A crash was imminent.

40/70

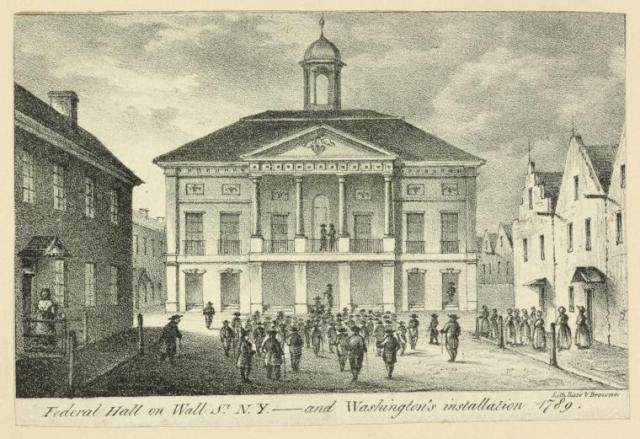

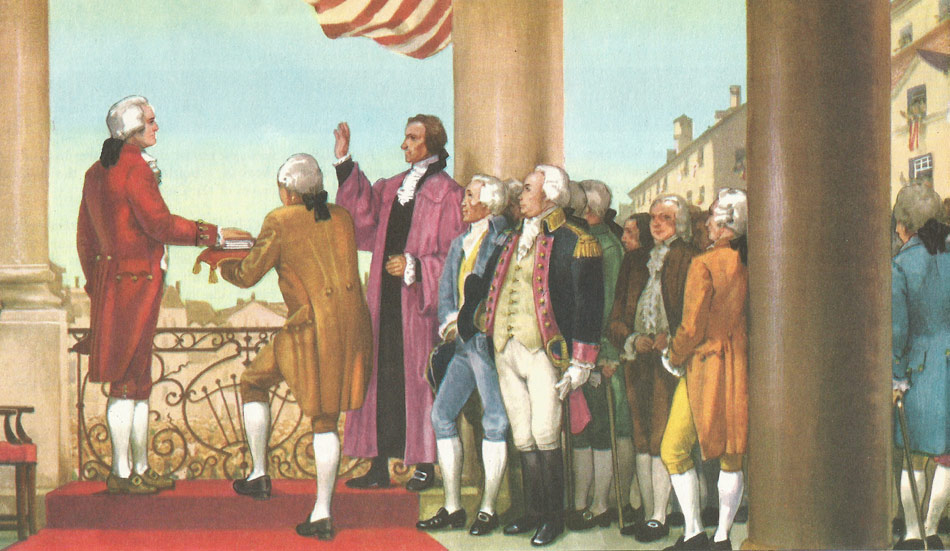

In 1789, Washington swore in as America& #39;s first President in the balcony of the City Hall built by Dutch slavers right here. And New York became capital of the new government. Much of Wall Street bond trading those days took place under a buttonwood tree.

In 1789, Washington swore in as America& #39;s first President in the balcony of the City Hall built by Dutch slavers right here. And New York became capital of the new government. Much of Wall Street bond trading those days took place under a buttonwood tree.

41/70

This brought changes. City Hall was now Federal Hall and the seat of the new Congress (no Capitol Building back then). Alexander Hamilton, the new Secretary of Treasury moved into a house on the Wall Street, as did many other Senators and Congressmen.

This brought changes. City Hall was now Federal Hall and the seat of the new Congress (no Capitol Building back then). Alexander Hamilton, the new Secretary of Treasury moved into a house on the Wall Street, as did many other Senators and Congressmen.

42/70

Wall Street coffee houses soon became a bustling rendezvous for lawmakers and traders. This made Philadelphia uneasy. Soon, Chestnut Street heavyweights started lobbying for government attention. Goal? Move capital moved from NY to Philadelphia. They had a trump card too.

Wall Street coffee houses soon became a bustling rendezvous for lawmakers and traders. This made Philadelphia uneasy. Soon, Chestnut Street heavyweights started lobbying for government attention. Goal? Move capital moved from NY to Philadelphia. They had a trump card too.

43/70

This trump card was the Bank of North America, the only nationally chartered bank in the country. To boost their chances further, they set up the Board of Brokers of Philadelphia in 1790. The capital now moved from NY to Philly. The lobbying worked!

This trump card was the Bank of North America, the only nationally chartered bank in the country. To boost their chances further, they set up the Board of Brokers of Philadelphia in 1790. The capital now moved from NY to Philly. The lobbying worked!

44/70

By 1792, the crash that was imminent, finally happened; precipitated by one man and his resource-transcending ambitions. The man was William Duer. He had recently started a speculation business called "The Six Per Cent Club."

By 1792, the crash that was imminent, finally happened; precipitated by one man and his resource-transcending ambitions. The man was William Duer. He had recently started a speculation business called "The Six Per Cent Club."

45/70

Riding the sharp bull run, Duer and his partners used a lot of amateur investors& #39; money to buy securities hoping to sell those later at a profit. By mid-1792 though, things started going south and Duer and his partners were left with obligations they couldn& #39;t fulfill.

Riding the sharp bull run, Duer and his partners used a lot of amateur investors& #39; money to buy securities hoping to sell those later at a profit. By mid-1792 though, things started going south and Duer and his partners were left with obligations they couldn& #39;t fulfill.

46/70

This doomed Duer who had gone under a mountain of debts riding the bubble and was now left holding papers worth a pittance. Accused of many other financial misdemeanors, Duer soon ended up in the debtors& #39; prison, pretty much for the rest of his life.

This doomed Duer who had gone under a mountain of debts riding the bubble and was now left holding papers worth a pittance. Accused of many other financial misdemeanors, Duer soon ended up in the debtors& #39; prison, pretty much for the rest of his life.

47/70

This crash changed how Wall Street conducted itself. On May 17, 1792, 24 traders met under the same buttonwood tree to sign a document to prevent a repeat of Duer-like manipulation. Indian cotton traders would do the same under a banyan tree in Bombay some 60 years later.

This crash changed how Wall Street conducted itself. On May 17, 1792, 24 traders met under the same buttonwood tree to sign a document to prevent a repeat of Duer-like manipulation. Indian cotton traders would do the same under a banyan tree in Bombay some 60 years later.

48/70

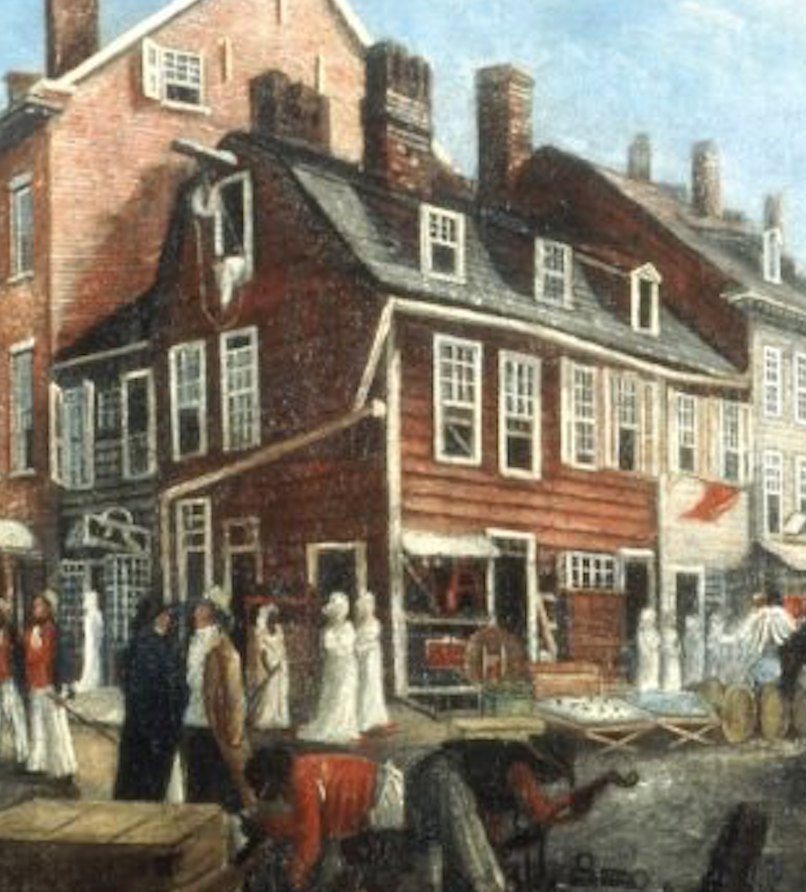

This was the Buttonwood Agreement. The idea was to keep auctioneers and manipulators out of the system.

The New York Stock Exchange was born.

By next year, business moved into a Tontine Coffee House, an establishment set up for this very purpose at 82 Wall Street.

This was the Buttonwood Agreement. The idea was to keep auctioneers and manipulators out of the system.

The New York Stock Exchange was born.

By next year, business moved into a Tontine Coffee House, an establishment set up for this very purpose at 82 Wall Street.

49/70

This coffee house would be Wall Street& #39;s new stock trading hub for over 2 decades. This move was necessary to keep the outsiders out. Non-member auctioneers and speculators had to be kept out of the loop and open-air trading defeated that purpose. Hence the coffee house.

This coffee house would be Wall Street& #39;s new stock trading hub for over 2 decades. This move was necessary to keep the outsiders out. Non-member auctioneers and speculators had to be kept out of the loop and open-air trading defeated that purpose. Hence the coffee house.

50/70

The brokers met inside this coffee house twice a day for formal securities auctions. If you wanted to trade, you had to hire somebody who knew someone inside; you weren& #39;t allowed to participate directly. These were America& #39;s first stockbrokers.

The brokers met inside this coffee house twice a day for formal securities auctions. If you wanted to trade, you had to hire somebody who knew someone inside; you weren& #39;t allowed to participate directly. These were America& #39;s first stockbrokers.

51/70

At the time, securities of only 30 very reputed companies were traded inside. Bids were in increments of one-eighth of a dollar. Soon, however, trading of less reputed stocks was resumed on the street outside by people barred from entering the Tontine.

At the time, securities of only 30 very reputed companies were traded inside. Bids were in increments of one-eighth of a dollar. Soon, however, trading of less reputed stocks was resumed on the street outside by people barred from entering the Tontine.

52/70

Remember the bear-baiting arena on Wall Street? Well, now the legacy became an analogy for the stock market. Bears were traders who anticipated a drop in stock prices, bulls who anticipated a rise. This human bear-baiting would now become the archetype of stock trading.

Remember the bear-baiting arena on Wall Street? Well, now the legacy became an analogy for the stock market. Bears were traders who anticipated a drop in stock prices, bulls who anticipated a rise. This human bear-baiting would now become the archetype of stock trading.

53/70

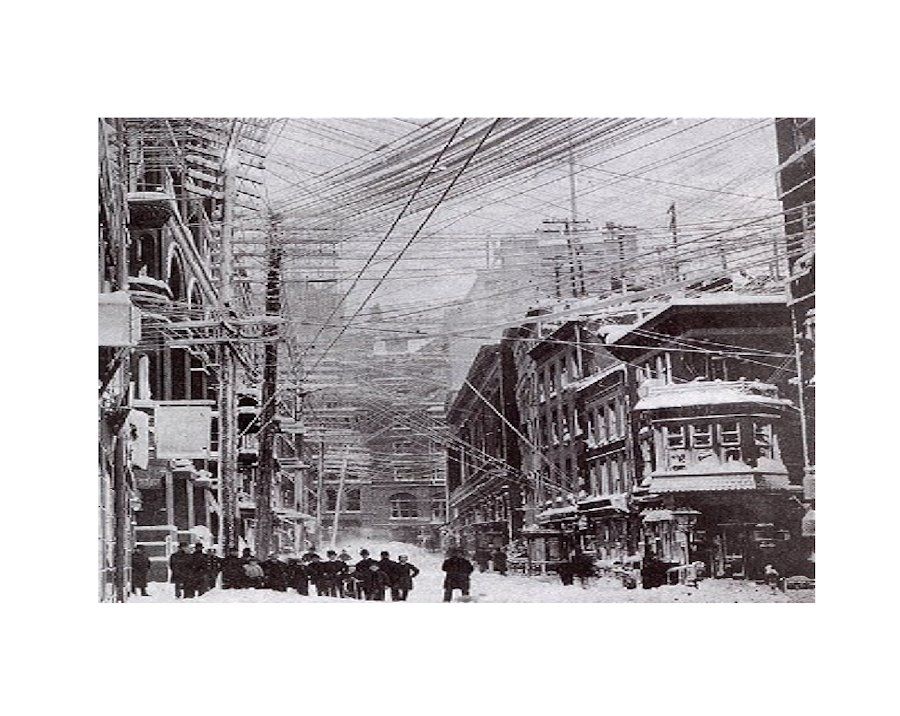

In 1832, Samuel Morse invented the telegraph and changed trading forever. News of price moves could travel between markets almost instantly. Morse set up shop on Wall Street where he charged brokers 25 cents for a demo. Soon, telegraph lines littered the landscape.

In 1832, Samuel Morse invented the telegraph and changed trading forever. News of price moves could travel between markets almost instantly. Morse set up shop on Wall Street where he charged brokers 25 cents for a demo. Soon, telegraph lines littered the landscape.

54/70

The telegraph helped NY snag its place on top of the nation& #39;s commercial totem pole from Philadelphia. That& #39;s because with the near-instant availability of price information, you no longer needed so many regional exchanges anymore. Things were about to get even bigger.

The telegraph helped NY snag its place on top of the nation& #39;s commercial totem pole from Philadelphia. That& #39;s because with the near-instant availability of price information, you no longer needed so many regional exchanges anymore. Things were about to get even bigger.

55/70

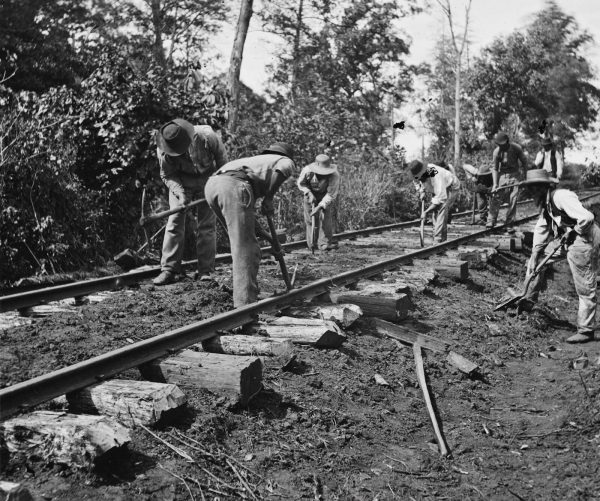

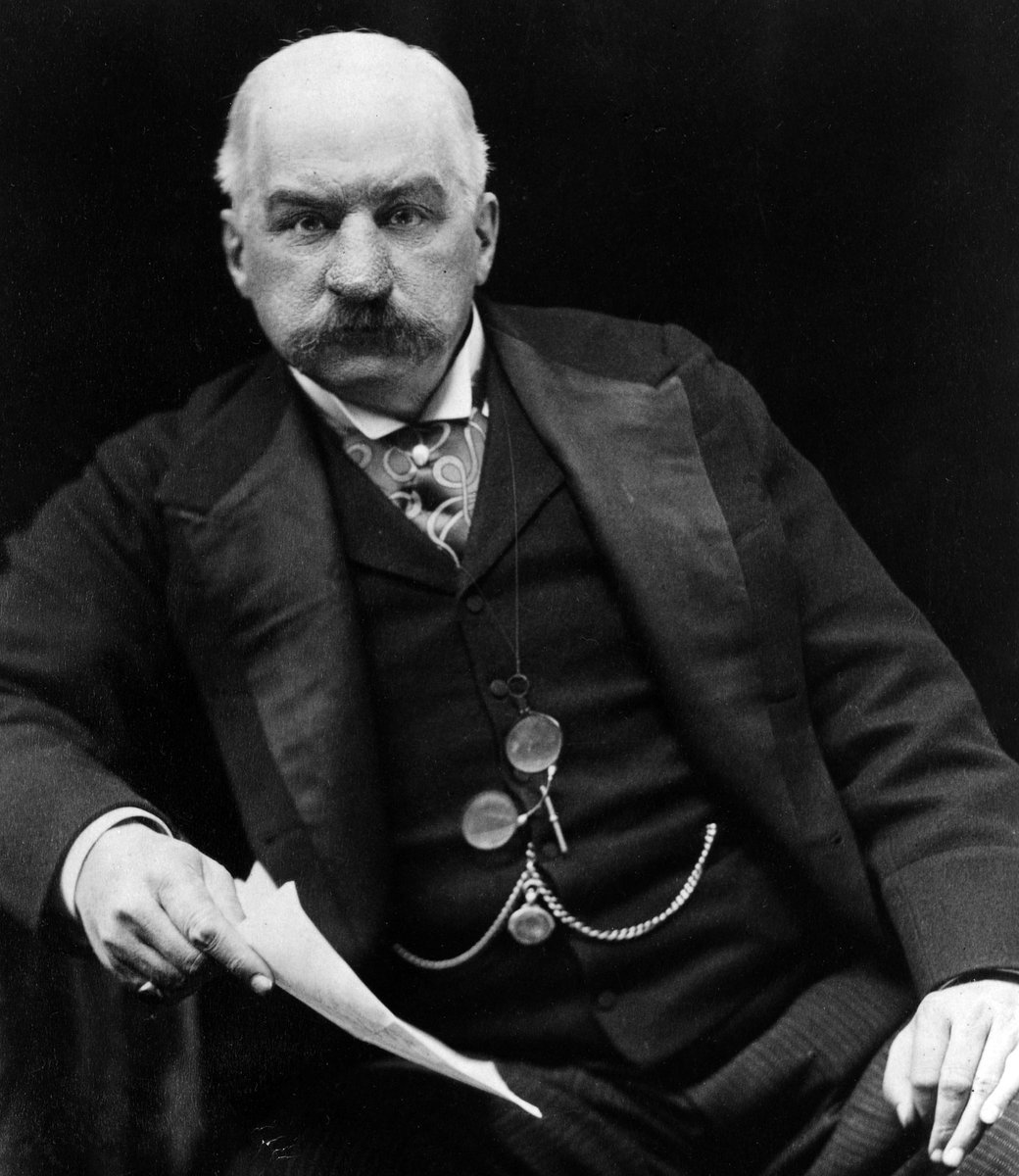

As Wall Street grew in both repute and prosperity, so did America. Its westward expansion fueled a rapid railroad boom, one that gave birth to some of the wealthiest names in the world such as J P Morgan, Cornelius Vanderbilt and Jay Gould.

As Wall Street grew in both repute and prosperity, so did America. Its westward expansion fueled a rapid railroad boom, one that gave birth to some of the wealthiest names in the world such as J P Morgan, Cornelius Vanderbilt and Jay Gould.

56/70

In 1861, America went to war. Again. With itself. The South seceded and declared independence from the rest of the Union over Lincoln& #39;s anti-slavery move. What came out of this was a Civil War that lasted 4 years and left over a million dead. Including Lincoln himself.

In 1861, America went to war. Again. With itself. The South seceded and declared independence from the rest of the Union over Lincoln& #39;s anti-slavery move. What came out of this was a Civil War that lasted 4 years and left over a million dead. Including Lincoln himself.

57/70

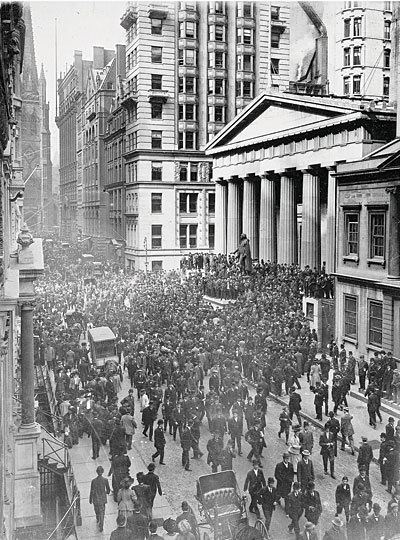

By the time this war ended, the railroad boom had spawned many new companies, ergo more stocks to trade. To accommodate this volume, NYSE needed a new home, something bigger than a coffee house. After several moves, the NYSE finally moved into its current location in 1865.

By the time this war ended, the railroad boom had spawned many new companies, ergo more stocks to trade. To accommodate this volume, NYSE needed a new home, something bigger than a coffee house. After several moves, the NYSE finally moved into its current location in 1865.

58/70

This was a swanky new place. The ventilation system blasted perfumed air to create a pleasant trading atmosphere across the crowded trading floor. The basement was fitted with vaults to protect stock certificates from elements. This was one sophisticated place.

This was a swanky new place. The ventilation system blasted perfumed air to create a pleasant trading atmosphere across the crowded trading floor. The basement was fitted with vaults to protect stock certificates from elements. This was one sophisticated place.

59/70

Remember those kerbside traders who started their own exchange outside the Tontine because they weren& #39;t allowed in? Well, they had by now organized too. They called themselves the Open Board of Stock Brokers and were beginning to rival NYSE in trading volumes and repute.

Remember those kerbside traders who started their own exchange outside the Tontine because they weren& #39;t allowed in? Well, they had by now organized too. They called themselves the Open Board of Stock Brokers and were beginning to rival NYSE in trading volumes and repute.

60/70

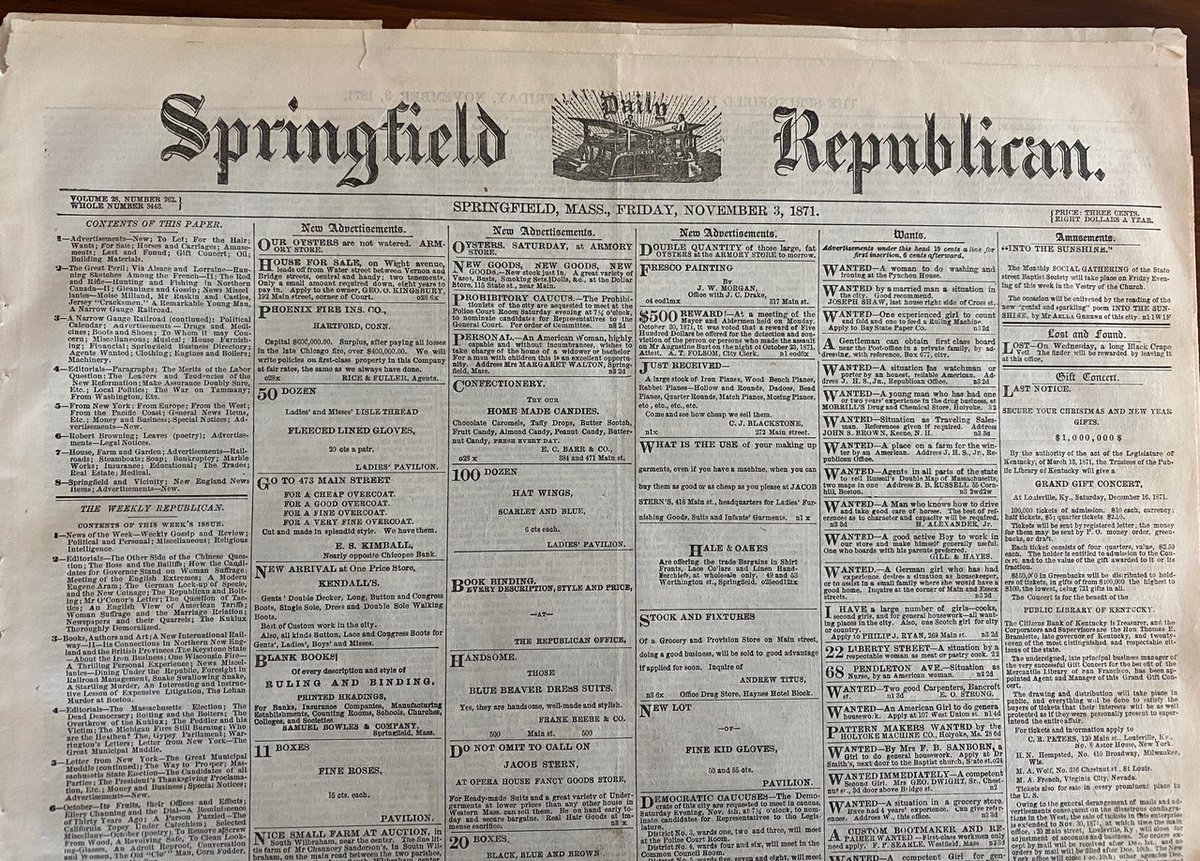

In 1869, the Open Board merged with NYSE and the stock auctioning system gave way to a free-for-all paradigm. 2 years later in 1871, a 21 year old boy traveled from Connecticut to Springfield, Massachusetts to work for the Springfield Daily Republican as a reporter.

In 1869, the Open Board merged with NYSE and the stock auctioning system gave way to a free-for-all paradigm. 2 years later in 1871, a 21 year old boy traveled from Connecticut to Springfield, Massachusetts to work for the Springfield Daily Republican as a reporter.

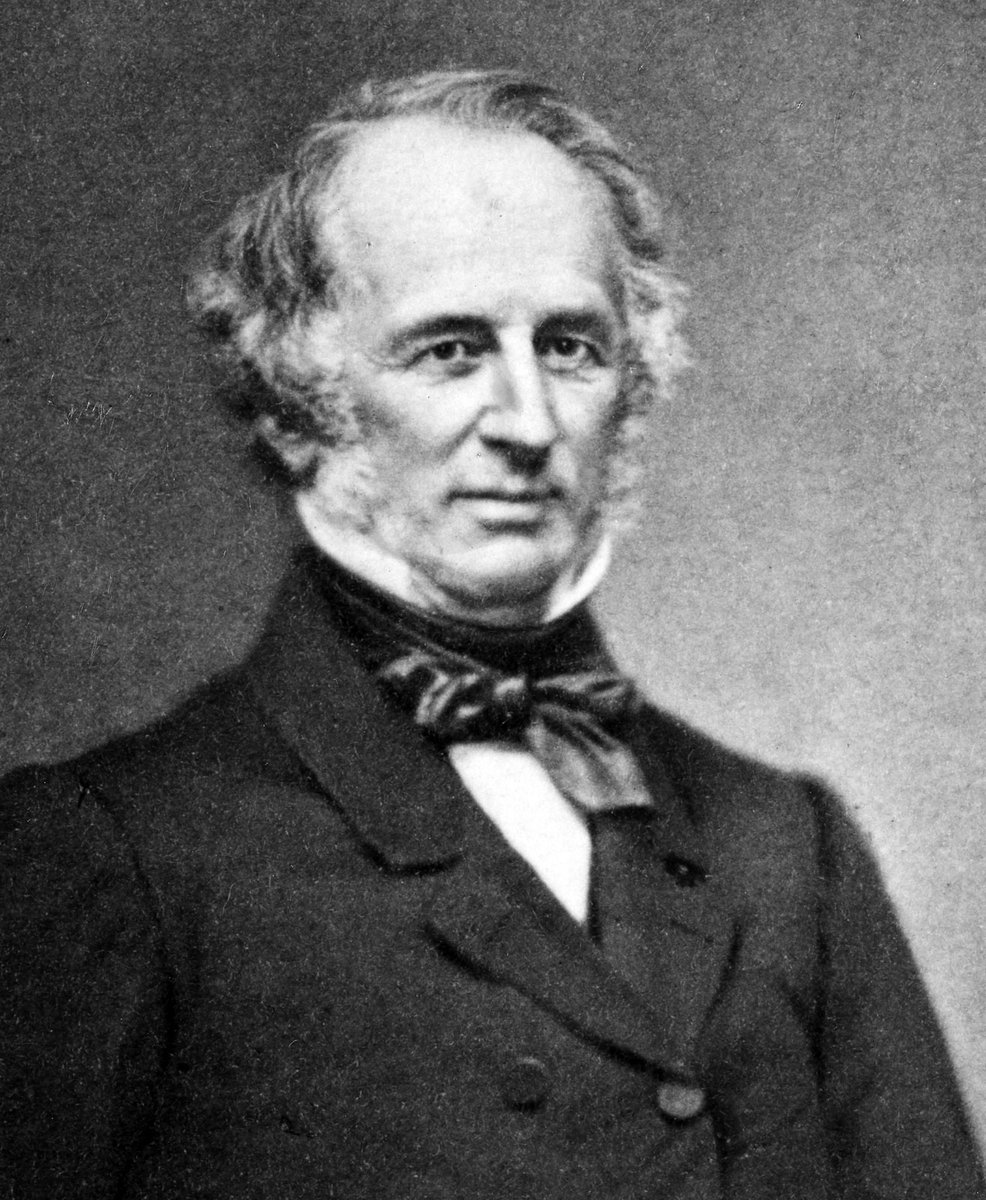

61/70

During his 3-year stint there, the boy learned to write crisp detailed articles and perfected his skills. In 1875, he moved to Rhode Island where he worked with The Providence Journal. This is where he got his break writing business stories.

During his 3-year stint there, the boy learned to write crisp detailed articles and perfected his skills. In 1875, he moved to Rhode Island where he worked with The Providence Journal. This is where he got his break writing business stories.

62/70

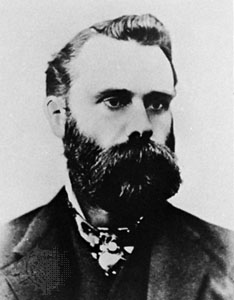

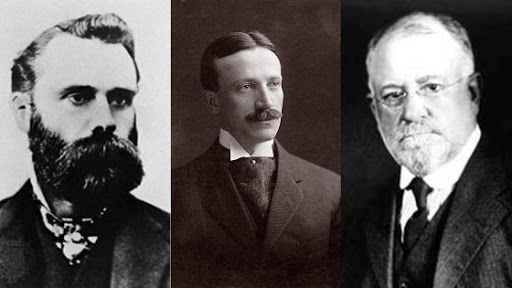

Finally in 1880, after having published 2 volumes and dozens of business articles, Charles Henry Dow finally arrived in New York. Here, when asked to find a writing partner for a business publication, Dow recommended a friend he had worked with in Providence. Edward Jones.

Finally in 1880, after having published 2 volumes and dozens of business articles, Charles Henry Dow finally arrived in New York. Here, when asked to find a writing partner for a business publication, Dow recommended a friend he had worked with in Providence. Edward Jones.

63/70

Working together on the Wall Street, Dow and Jones realized that business journalism on the Street was far from fair and there was a vacuum they could fill. In Nov 1882, they joined forces with financier Charles Bergstresser and started Dow, Jones & Company.

Working together on the Wall Street, Dow and Jones realized that business journalism on the Street was far from fair and there was a vacuum they could fill. In Nov 1882, they joined forces with financier Charles Bergstresser and started Dow, Jones & Company.

64/70

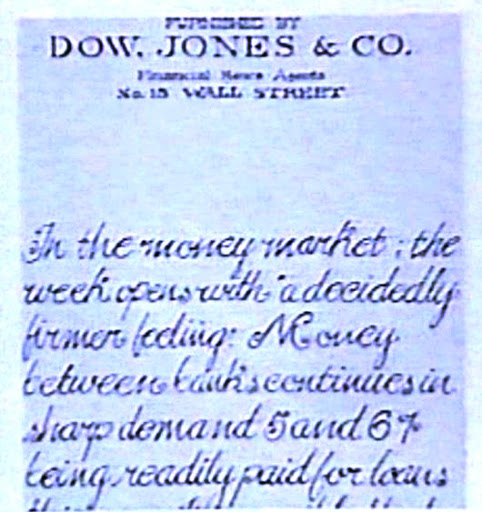

The business was headquartered in the basement of a candy store. They kept it simple. Throughout the early years, they& #39;d print brief news bulletins with key market updates and hand-deliver copies to the traders at the exchange. These were called flimsies.

The business was headquartered in the basement of a candy store. They kept it simple. Throughout the early years, they& #39;d print brief news bulletins with key market updates and hand-deliver copies to the traders at the exchange. These were called flimsies.

65/70

By Nov 1883, the flimsies had graduated to a better-organized 2-page daily named Customers& #39; Afternoon Letter. This was a summary of the day& #39;s trades and price-moves and soon earned a reputation among investors with a circulation of over a thousand.

By Nov 1883, the flimsies had graduated to a better-organized 2-page daily named Customers& #39; Afternoon Letter. This was a summary of the day& #39;s trades and price-moves and soon earned a reputation among investors with a circulation of over a thousand.

66/70

Those days, stock markets were the financial world& #39;s Wild West. It was incredibly hard to keep track of market moves as there was no way to consolidate the myriad scrips and their performance. There was no way to tell how the market was doing overall. This changed in 1885.

Those days, stock markets were the financial world& #39;s Wild West. It was incredibly hard to keep track of market moves as there was no way to consolidate the myriad scrips and their performance. There was no way to tell how the market was doing overall. This changed in 1885.

67/70

In 1885, Dow, Jones, and Company launched a system to track the market in a way that you didn& #39;t have to track individual stock prices. This was the Dow Jones Stock Average, a price average of 11 stocks — 9 railroad companies, 1 steamship company, and Western Union.

In 1885, Dow, Jones, and Company launched a system to track the market in a way that you didn& #39;t have to track individual stock prices. This was the Dow Jones Stock Average, a price average of 11 stocks — 9 railroad companies, 1 steamship company, and Western Union.

68/70

Now, tracking the exchange was as easy as following this index. If it went up, the market was doing well, otherwise bad. No need to track individual scrips anymore. DJSA was the precursor to the 30-stock Dow Jones Industrial Average that we have today.

Now, tracking the exchange was as easy as following this index. If it went up, the market was doing well, otherwise bad. No need to track individual scrips anymore. DJSA was the precursor to the 30-stock Dow Jones Industrial Average that we have today.

69/70

One day, Dow and Jones decided it was time to upgrade. So they turned the Customers& #39; Afternoon Letter into a new bigger newspaper with organized columns and listings. While Jones managed desk work, Dow took up editing. A staff of 50 handle everything else.

One day, Dow and Jones decided it was time to upgrade. So they turned the Customers& #39; Afternoon Letter into a new bigger newspaper with organized columns and listings. While Jones managed desk work, Dow took up editing. A staff of 50 handle everything else.

70/70

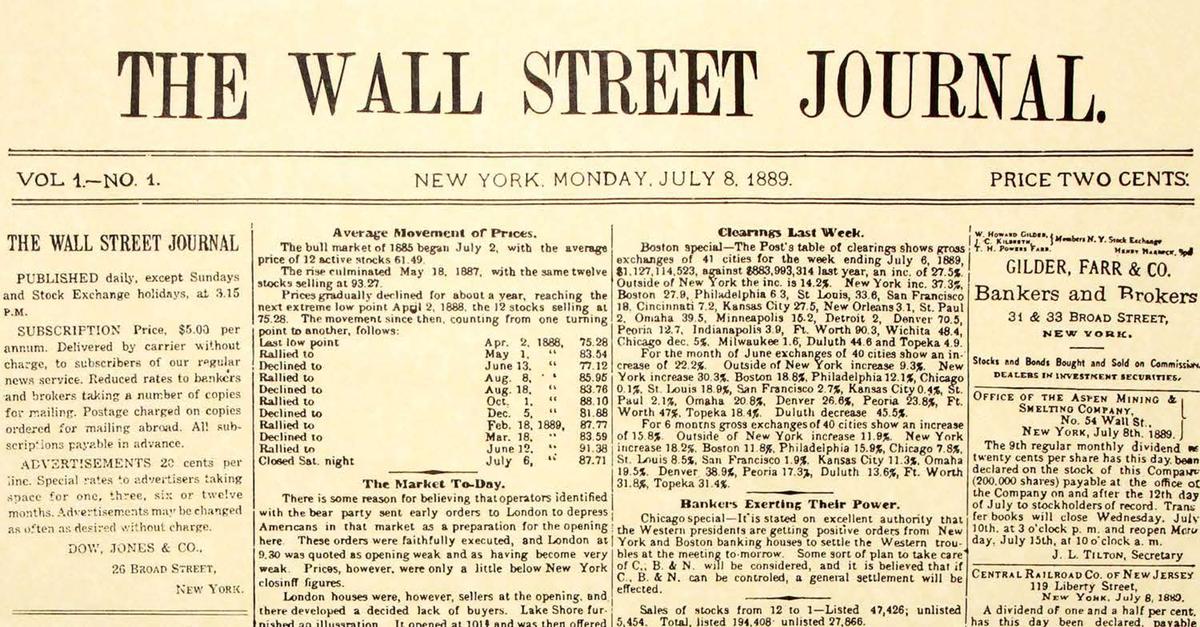

With much fanfare, the first issue of this new business daily launched on July 8, 1889. Priced at 2 cents a copy.

Unassumingly named, you guessed it.

Here& #39;s wishing @WSJ a very happy 131st birthday.

With much fanfare, the first issue of this new business daily launched on July 8, 1889. Priced at 2 cents a copy.

Unassumingly named, you guessed it.

Here& #39;s wishing @WSJ a very happy 131st birthday.

References:

- The Big Board: A History of the New York Stock Market by Robert Sobel

- A Cultural History of Finance by Irene Finel-Honigman

- The Big Board: A History of the New York Stock Market by Robert Sobel

- A Cultural History of Finance by Irene Finel-Honigman

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter![[THREAD: THE WALL STREET JOURNAL]1/70Long before there was an America or an England, Roman ships were carrying wine and gold to India and returning with spices, silk, and exotic animals. These trades were extremely profitable. And risky. Because bad weather and pirates. [THREAD: THE WALL STREET JOURNAL]1/70Long before there was an America or an England, Roman ships were carrying wine and gold to India and returning with spices, silk, and exotic animals. These trades were extremely profitable. And risky. Because bad weather and pirates.](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EcZ1pqpVcAAe0Zc.jpg)