MAHJARI PRINT CULTURE: Now, let& #39;s talk about Syrian serials in this diaspora.

Yesterday I described the problems in locating migration history in state records when states are invested in migration control.

Thankfully, Syrian emigrants were prolific printers.

au: @SDFahrenthold

Yesterday I described the problems in locating migration history in state records when states are invested in migration control.

Thankfully, Syrian emigrants were prolific printers.

au: @SDFahrenthold

The late 19th century was the era of newsprint globally, and in the Arabophone Middle East, print culture was closely associated with the experience of exile/diaspora.

Printing was initially controlled by the Ottoman state, but in the 1870s private presses appeared.

Printing was initially controlled by the Ottoman state, but in the 1870s private presses appeared.

Private newspapers run by Syrian emigres appeared in Egypt first.

- al-Ahram in 1875

- al-Muqtataf in 1876

- al-Muqattam in 1889

- al-Hilal in 1892

On Egypt and print culture and its politics, check out Khuri-Makdisi& #39;s work: https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520280144/the-eastern-mediterranean-and-the-making-of-global-radicalism-1860-1914">https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780...

- al-Ahram in 1875

- al-Muqtataf in 1876

- al-Muqattam in 1889

- al-Hilal in 1892

On Egypt and print culture and its politics, check out Khuri-Makdisi& #39;s work: https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520280144/the-eastern-mediterranean-and-the-making-of-global-radicalism-1860-1914">https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780...

Under British rule and beyond the Ottoman domain, Cairo was a destination for Syrian intellectuals and writers, particularly those of the liberal, radical, or secular persuasion. Cairo& #39;s Arab Nahda ("renaissance") is one of the most remarked epochs in Middle East history.

Cairo was simultaneously a waypoint for an entire generation of Syrian men who later became the most famous printers in the Syrian Americas.

Syrian journalists came to Cairo to write editorials for one of the city& #39;s papers before boarded a steamship for USA, Brazil, or Argentina.

Syrian journalists came to Cairo to write editorials for one of the city& #39;s papers before boarded a steamship for USA, Brazil, or Argentina.

By the 1890s, the Syrian colonies (jaliyyat) abroad could sustain a print media market. Syrian printers came & founded serials.

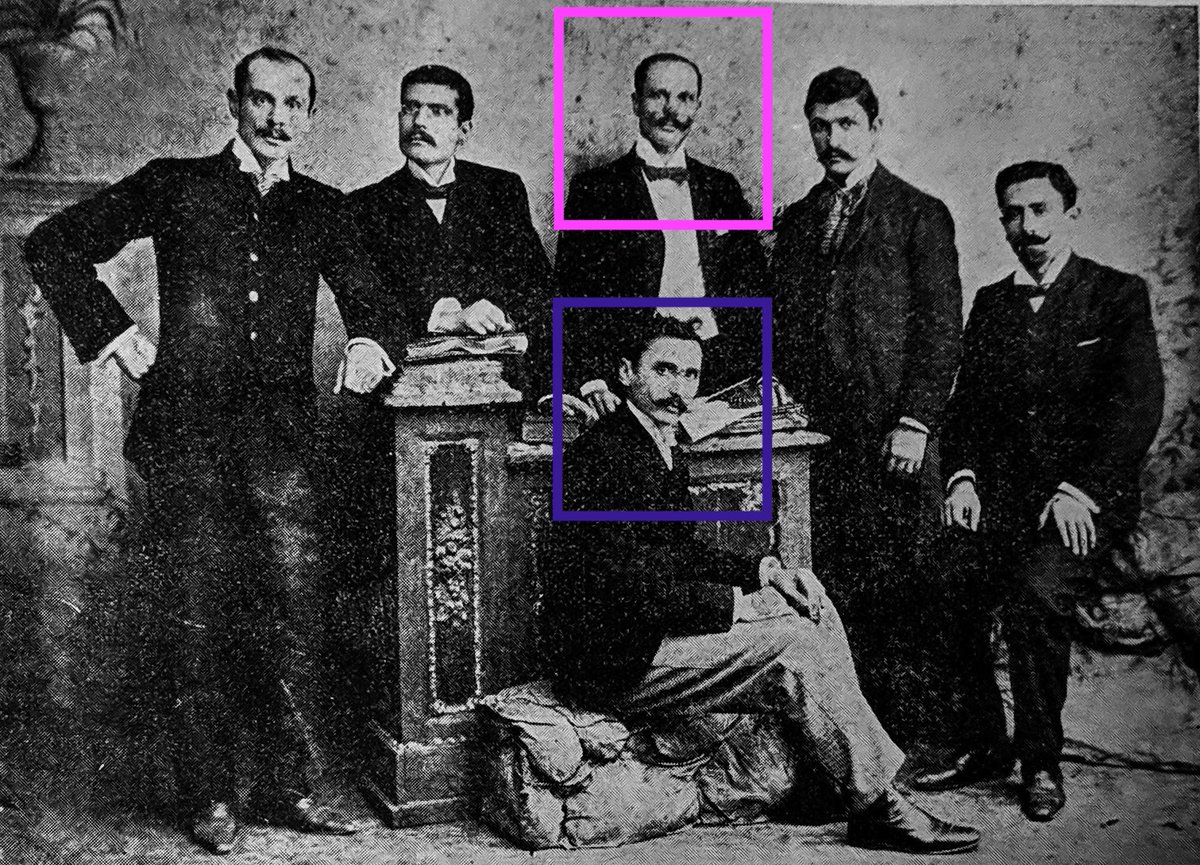

Image: 1902 Brazil. From R: Shukri Jirji Antun; Faris Sam& #39;an Najm; Qaysar Ibrahim Ma& #39;luf; Na& #39;um Labaki; Khalil al-Khuri Kassib. Seated: Shukri al-Khuri

Image: 1902 Brazil. From R: Shukri Jirji Antun; Faris Sam& #39;an Najm; Qaysar Ibrahim Ma& #39;luf; Na& #39;um Labaki; Khalil al-Khuri Kassib. Seated: Shukri al-Khuri

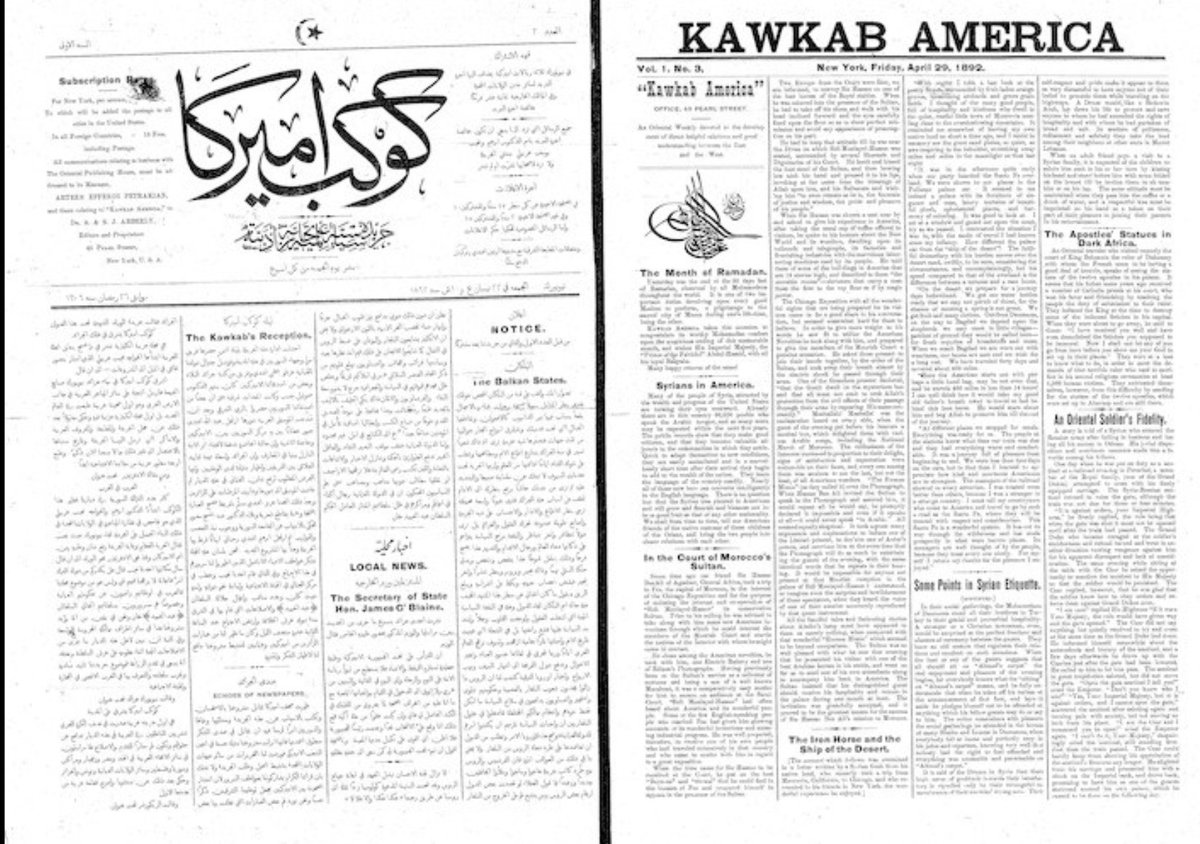

In the United States, Najib and Ibrahim Arbeely established Kawkab Amrika in New York City, 1892. New York City& #39;s Washington St neighborhood was by then already called "little Syria," and most of the Syrians who arrived in the states moved through it at some point.

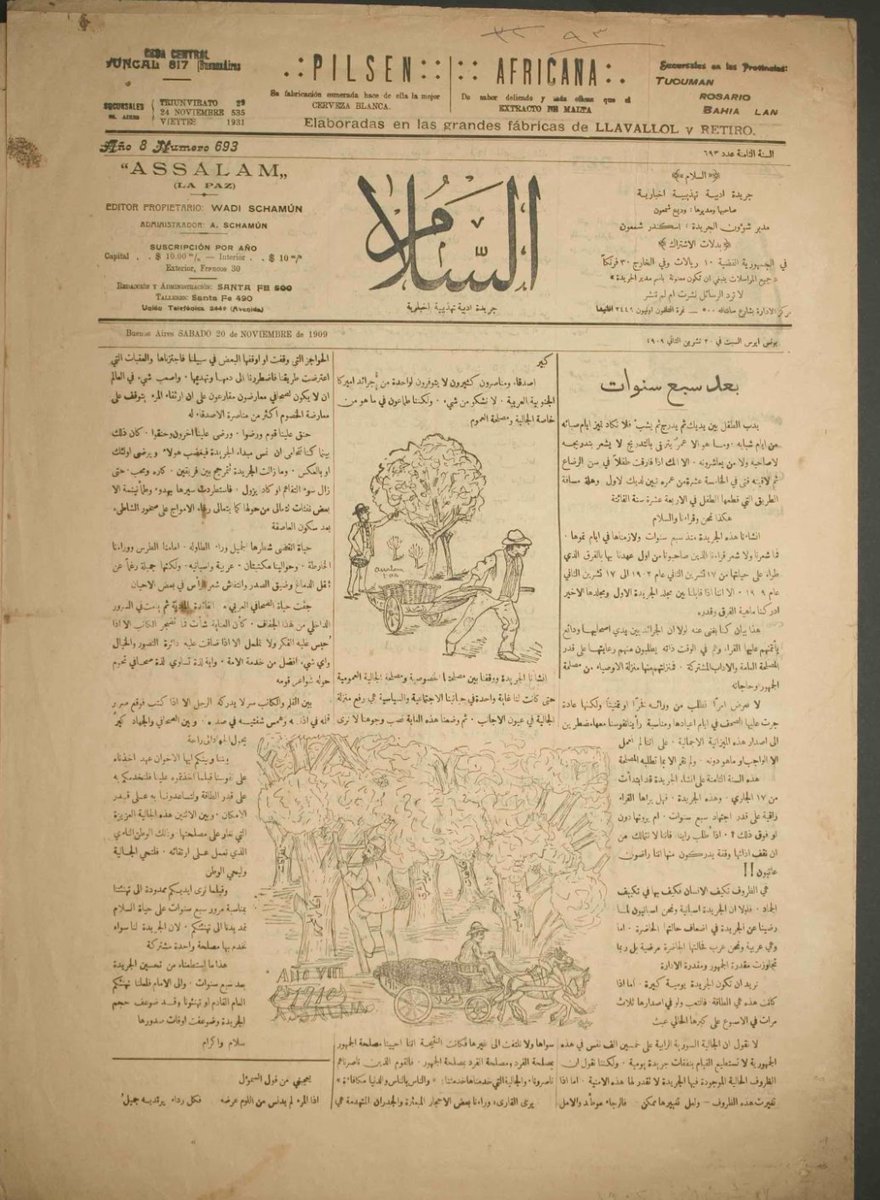

In Buenos Aires, the Schamun brothers opened Assalam (al-Salam) newspaper. It was one of dozens of titles that emerged in the city in the first decade of the 20th century.

Syrian printing houses opened in all corners of the Syrian American mahjar, but they all linked in a distinct chain to 1 of 3 print "capitals": São Paulo, Buenos Aires, & New York City. And each of those capitals was linked back to Cairo, Egypt.

A print cultural network formed.

A print cultural network formed.

Syrian papers in NYC, for instance, reprinted stories from Cairo& #39;s al-Muqtataf or al-Hilal, with commentary by local editors. Then, a Syrian paper in Sao Paulo reprinted that commentary, offering its own "take". Serials were syndicated but were also themselves sites of contest.

READING CULTURE: in the 3 print capitals of the Syrian mahjar, dozens of serials competed with one another for the attentions of a global Syrian reading public.

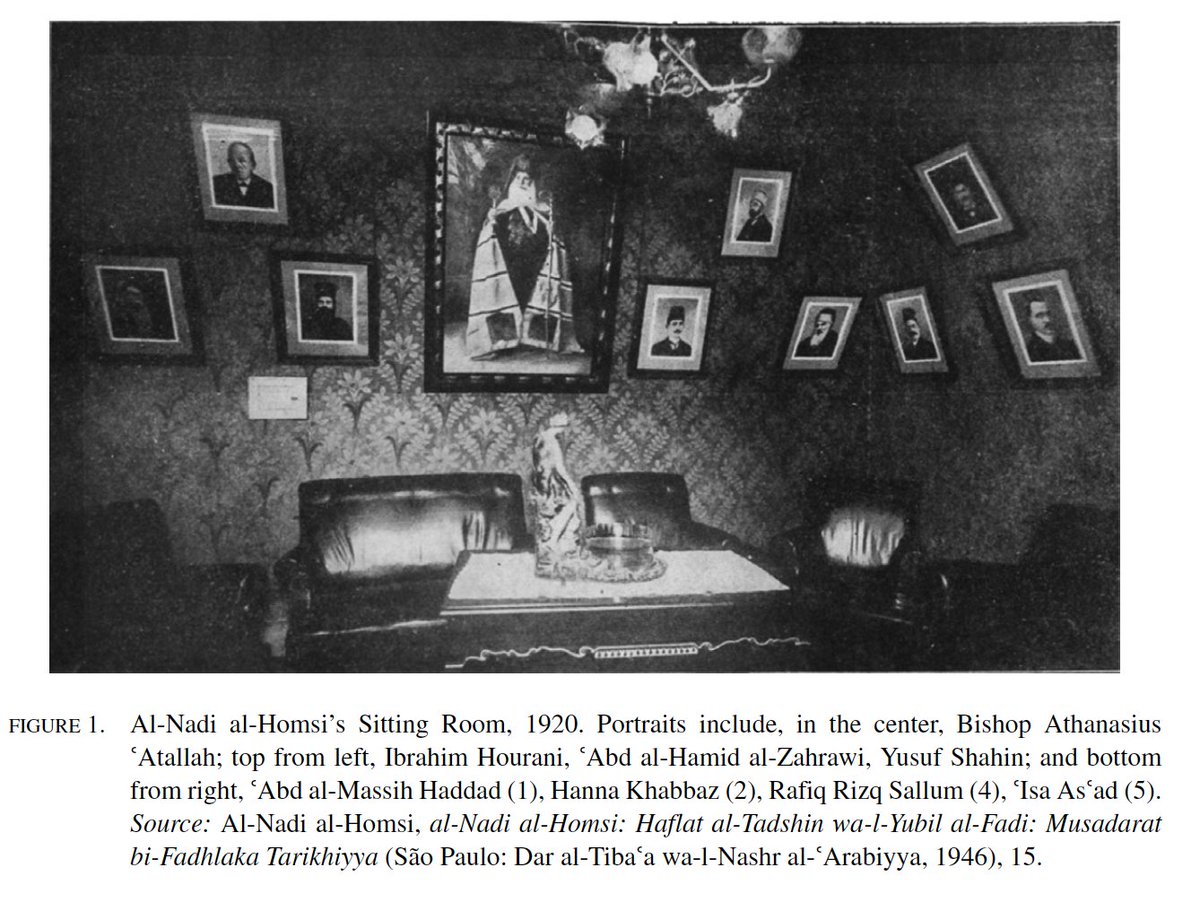

Many of them opened reading rooms with cafes and space to collectively read/discuss the news du jour.

Many of them opened reading rooms with cafes and space to collectively read/discuss the news du jour.

This is a reading culture that Ilham Khuri-Makdisi describes of Cairo, and Ami Ayalon describes of Palestine. But the places where Syrian newspapermen printed the news also became places where men (and it usually was male culture) debated the news as well.

Reading rooms were also an important part of Syrian associational culture. Within them, serials from all over the diaspora were collected; mail-order subscription made it possible to sit in Sao Paulo and read serials from Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Cuba, and the USA.

These reading rooms (& the serials & migrant associations they were attached to) took on political viewpoints, especially regarding homeland politics.

Pictured: a reading room space in Sao Paulo& #39;s Club Homs, with Arab nationalist icons on the walls.

Pictured: a reading room space in Sao Paulo& #39;s Club Homs, with Arab nationalist icons on the walls.

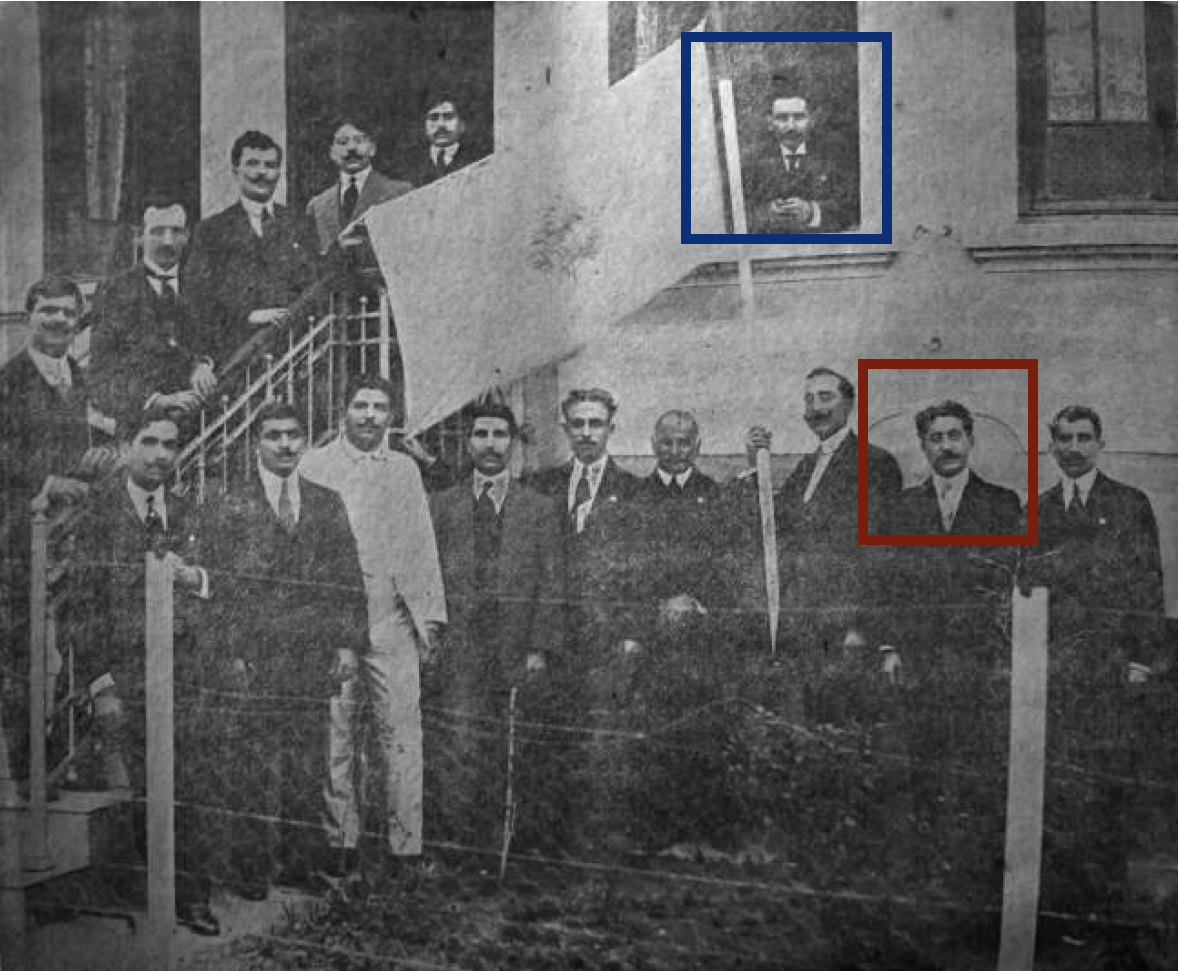

Syrian printers were so convinced that print culture was the way to shape Syrian political opinion that they led many of the mahjar& #39;s nationalist resistance groups. Here, in São Paulo, is Abu al-Hawl ed. Shukri al-Khuri & associates declaring revolt against the Ottoman Empire.

The Ottoman government also understood the power of the Syrian press in the mahjar. After the Young Turk Revolution of 1908, the empire& #39;s ruling party tried to reach out to Syrians living abroad by sponsoring mahjari newspapers to "reclaim" emigrants for the Ottoman Empire.

In 1910, the Ottoman ruling party (the Committee of Union and Progress) announced the creation of new Ottoman consulates in Syrian communities in Latin America.

Emir Amin Arslan came to Buenos Aires, opened his office, and granted Assalam newspaper state sponsorship.

Emir Amin Arslan came to Buenos Aires, opened his office, and granted Assalam newspaper state sponsorship.

Also in 1910, the new Ottoman consulate in São Paulo opened. Ready for this?

The consul general was Qaysar Maluf (pink rectangle). Maluf was then editor of al-Barazil.

And below him, Shukri al-Khuri (blue rectangle), who led a nationalist group against Ottoman rule in 1914.

The consul general was Qaysar Maluf (pink rectangle). Maluf was then editor of al-Barazil.

And below him, Shukri al-Khuri (blue rectangle), who led a nationalist group against Ottoman rule in 1914.

Here is the image of al-Khuri (in blue) declaring revolt in São Paulo.

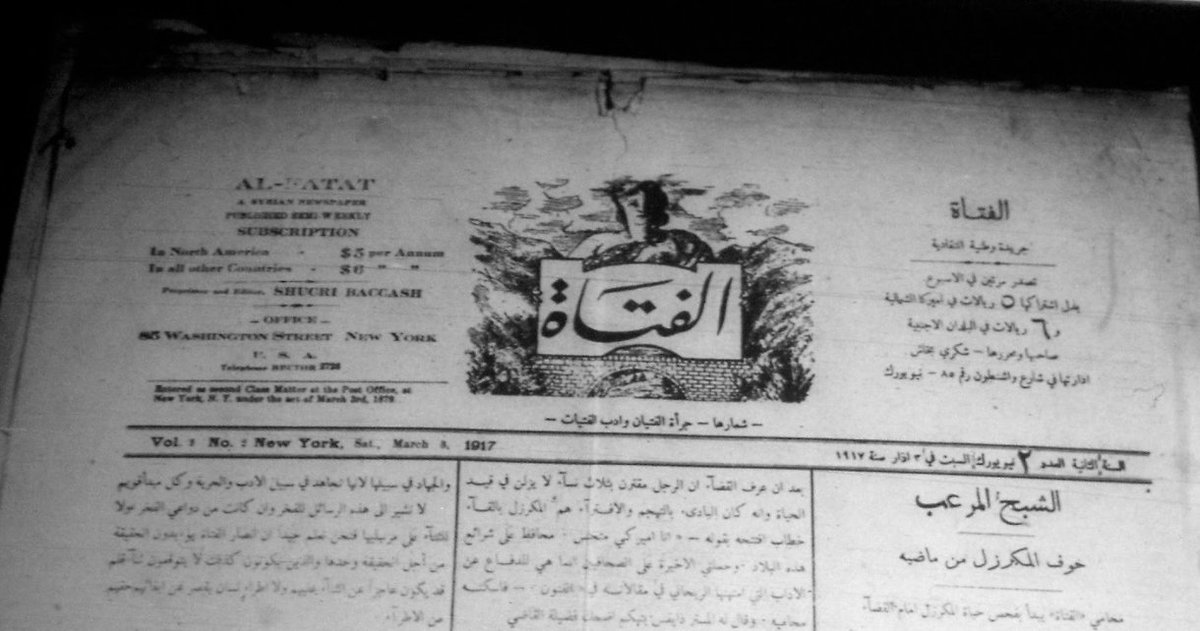

In red is Shukri al-Bakhkhash, who in 1917 relocated to New York City and was printing the Arab Nationalist newspaper, al-Fatat.

These guys traveled widely, along a print cultural network we can now track.

In red is Shukri al-Bakhkhash, who in 1917 relocated to New York City and was printing the Arab Nationalist newspaper, al-Fatat.

These guys traveled widely, along a print cultural network we can now track.

Control over the mahjari press was even a focus for foreign powers. During World War I (an event I& #39;ll discuss more tomorrow), the French Foreign Ministry started subsidizing Arabic serials in this diaspora in a campaign to bolster its claims to a Middle East Mandate.

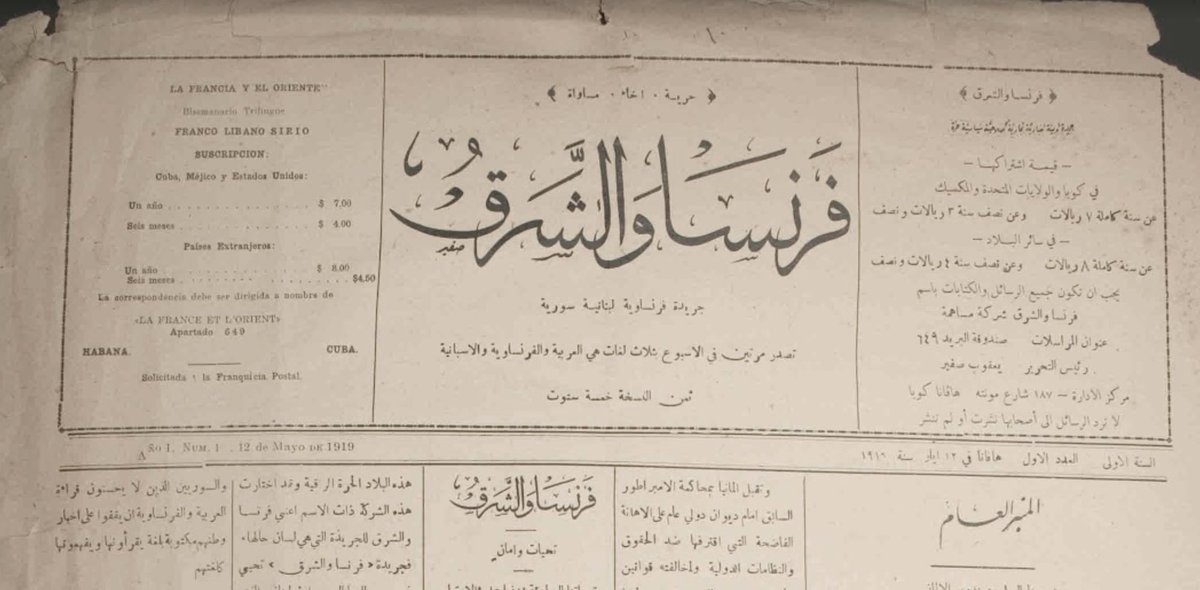

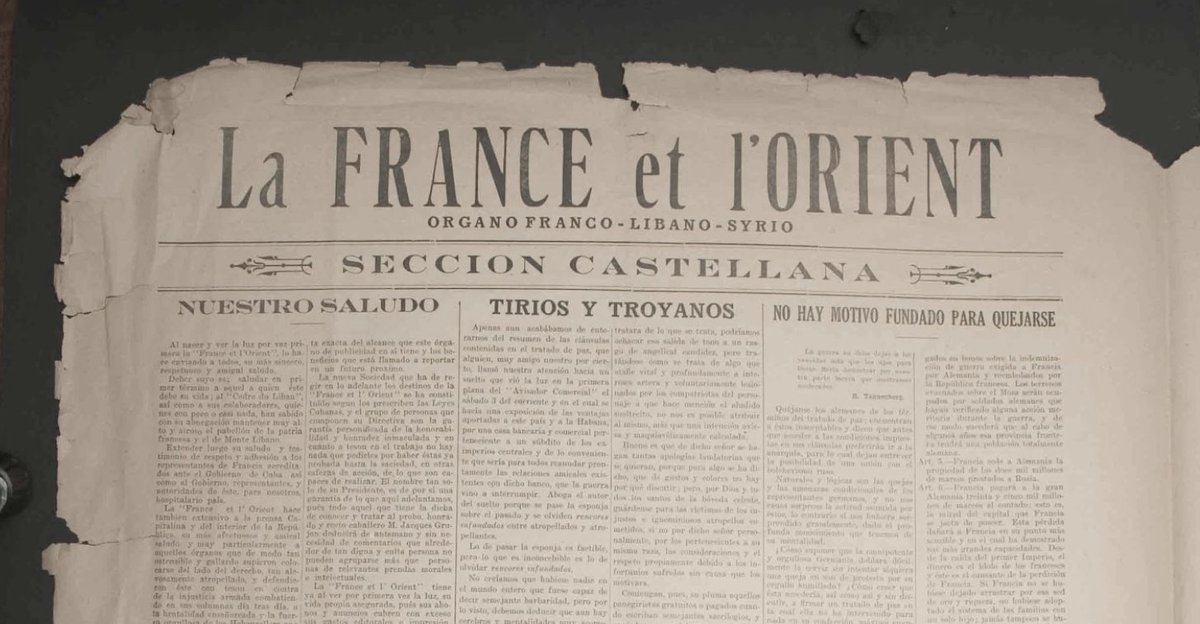

In Havana, Cuba in 1919, French consular staff joined Syrian emigre editors to produce Fransa wa-l-Sharq, a trilingual serial in Arabic, French, and Spanish that touted the "benefits" of French colonialism in the homeland.

The move was supposed to stanch nationalist sentiment.

The move was supposed to stanch nationalist sentiment.

What we& #39;re seeing here are the ways that print cultural networks facilitated the movement of emigre writers, their ideas, & political movements in the crucial period 1900-1914. We& #39;re also seeing attempts by states (Ottoman, French) to "break into" the business of Syrian printing.

TECHNOLOGY OF PRINTING: above I argue that print technology created new diasporic political connections in the mahjar.

But we can also flip that one its head, because technologies also moved across this space in important ways.

So, let& #39;s consider the press-as-machine.

But we can also flip that one its head, because technologies also moved across this space in important ways.

So, let& #39;s consider the press-as-machine.

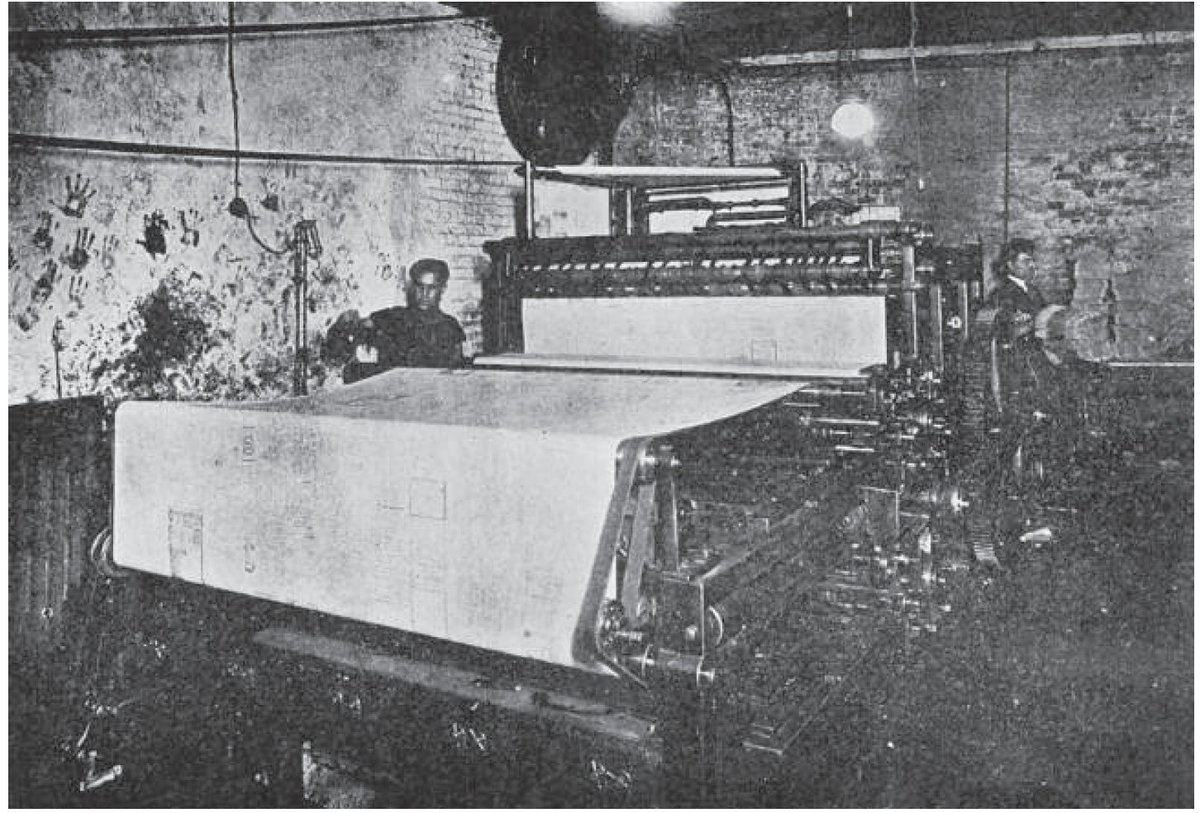

The turn-of-the-century printing presses were heavy and used metal plates to set type. For a history of Arabic letterpress printing in the 19th century, check out this blog by Hala Auji, author of Printing Arab Modernity: https://printinghistory.org/challenges-of-early-arabic-printing/">https://printinghistory.org/challenge...

The presses in Nahda-era Cairo used these metal letterpress machines, as did the very first Arabic newspapers in the Americas.

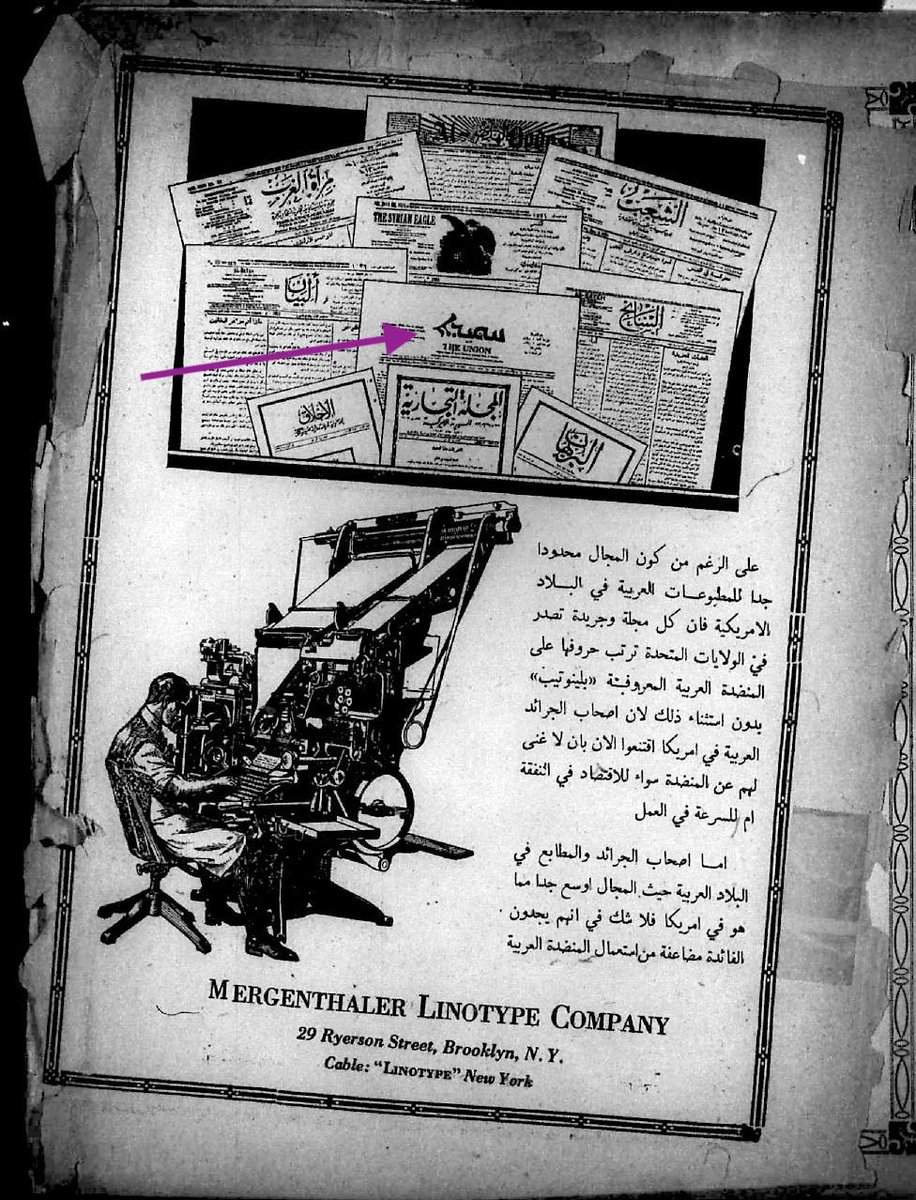

But in 1910, the Syrian American printer in New York, Sallum Mukarzil, developed a linotype machine for the Merganthaler Company (pictured).

But in 1910, the Syrian American printer in New York, Sallum Mukarzil, developed a linotype machine for the Merganthaler Company (pictured).

The Merganthaler machines made the composition and setting of Arabic letterpress faster, less specialized, and more comparable to typewriting than typesetting. It made Arabic newsprint cheaper to produce, and contributed to a blossoming of Arabic print across the Americas.

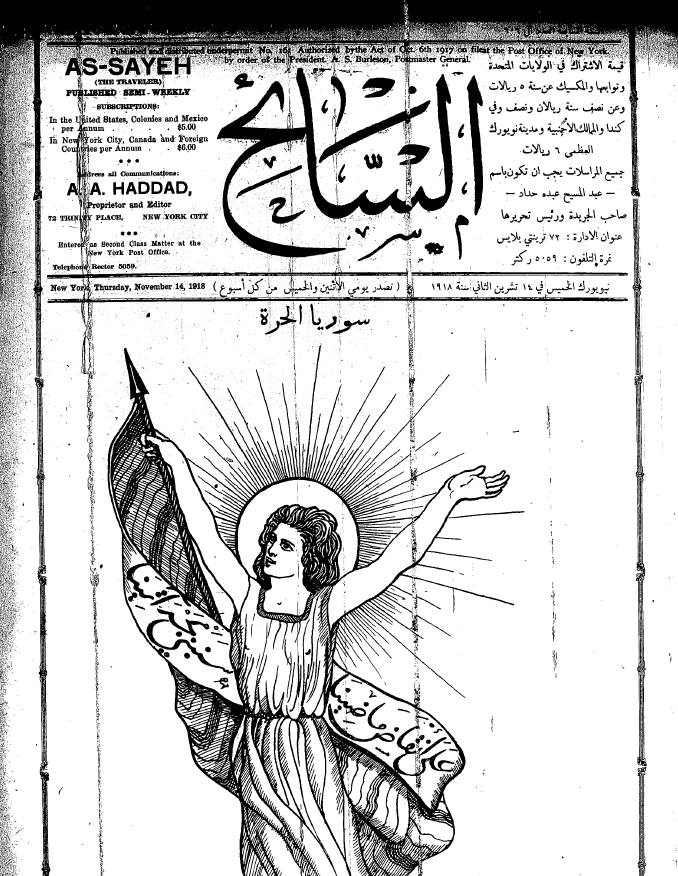

Look at this ad again. Within it, you see the Arabic dailies of NYC: al-Huda, al-Sha& #39;ab, al-Nasr, al-Sa& #39;ih, Mirat al-Gharb, al-Bayan, al-Akhlaq, al-Burhan, al-Majalla al-Tijariyya...

& the Assyrian Union (arrow). Merganthaler also revolutionized printing in Syriac and Assyrian.

& the Assyrian Union (arrow). Merganthaler also revolutionized printing in Syriac and Assyrian.

By the mid-1920s there were Arabic typewriters, facilitated by the Merganthaler machine and the ways that linotype printing helped standardized the Arabic letterforms in printing.

Celebrated litterateurs like Gibran, Naimy, Abu Madi were early adopters of these typewriters.

Celebrated litterateurs like Gibran, Naimy, Abu Madi were early adopters of these typewriters.

What happened to the old metal presses when the mahjari serials adopted new technologies? In at least one case, I discovered they sent them home to Syria.

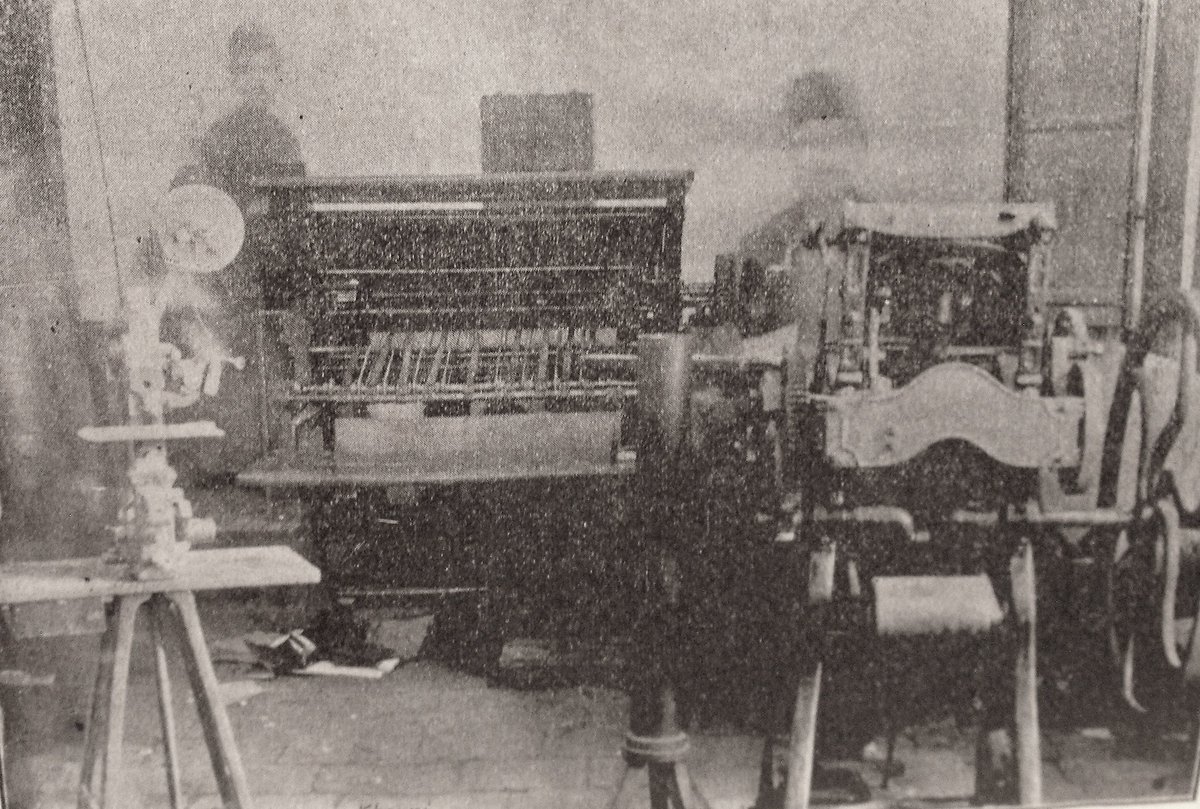

Here& #39;s Homs press (1909) sent to Homs, Syria from Sao Paulo by Bishara Moherdawi as a gift to the city& #39;s Orthodox community.

Here& #39;s Homs press (1909) sent to Homs, Syria from Sao Paulo by Bishara Moherdawi as a gift to the city& #39;s Orthodox community.

The press produced a number of serials, some related to the church and others of an Arab nationalist bent. Here& #39;s a 1914 issue of Homs newspaper.

Mahjari print culture came home. At a time when the Ottomans imposed increasing censorship, this was a revolutionary remittance.

Mahjari print culture came home. At a time when the Ottomans imposed increasing censorship, this was a revolutionary remittance.

I& #39;ll conclude today& #39;s thread on PRINT CULTURE with 2 images I love.

1. the printers have faded from this photograph, but their press/its papers remain. This reminds me to treat these serials not merely as texts but as artifacts into the lives of the people who produced them.

1. the printers have faded from this photograph, but their press/its papers remain. This reminds me to treat these serials not merely as texts but as artifacts into the lives of the people who produced them.

2. the inky handprints on the wall of this room remind me that mahjari serials--like lots of socially-produced records left by migrant communities but left out of state archives--have a subtextual goal.

"I was here!" say those handprints, "I was here, and I spilled the ink!"

"I was here!" say those handprints, "I was here, and I spilled the ink!"

Tomorrow, I will talk about the cataclysm that spilled a lot of ink in the Syrian mahjar: World War I, the fall of the Ottoman Empire, and the impact of Europe& #39;s partition of the Middle East on this diaspora, a half-million strong.

Look for WORLD WAR I IN THE MAHJAR in the AM!

Look for WORLD WAR I IN THE MAHJAR in the AM!

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter