Good news! I just got my first "Top 5" journal publication, in the Review of Economic Studies. Top 5 journals in econ are fetishized beyond belief. This publication helps show why we might want a more balanced attitude. #Econtwitter https://ideas.repec.org/p/abo/neswpt/w0264.html">https://ideas.repec.org/p/abo/nes...

In our paper, we find several coding errors which overturn a seminal paper in the "Chinese competition caused a huge increase in innovation" lit by Bloom et al (BDvR). From the beginning, I knew the BDvR paper had problems. Why? https://nbloom.people.stanford.edu/sites/g/files/sbiybj4746/f/titc1.pdf">https://nbloom.people.stanford.edu/sites/g/f...

Well, first I should say that I am actually somewhat empathetic about the coding errors, common in published papers--a reason we need replication. Any empirical researcher will make mistakes on occasion. But, there is a lot to chew on in this case besides the coding errors.

First, intuitively, the idea that Chinese competition directly led to up to 50% of the increase in patenting, computer purchases, and TFP growth in Europe from roughly 1996-2005 seemed unlikely. This from a relatively small increase in trade concentrated in a few sectors?

Second, BDvR& #39;s identification strategy is a diff-in-diff, a comparison of firms in sectors that compete with China before and after China joined the WTO. Yet, the authors didn& #39;t plot pre-treatment trends. Moreover, they didn& #39;t plot any relevant data. Red flags everywhere.

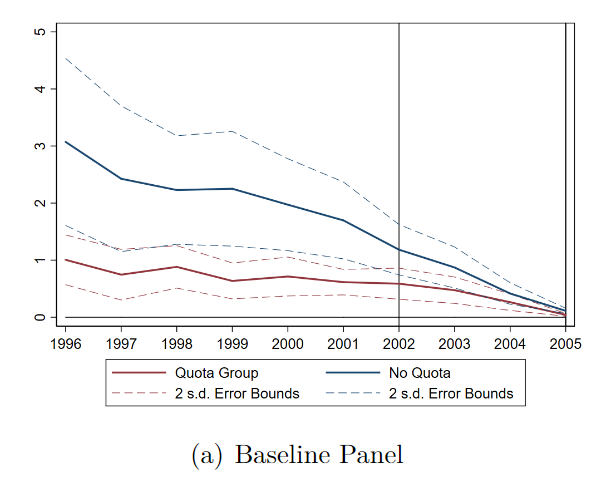

Thus, one of the first things we did was merely plot the pre- and post-treatment trends for patents. Here& #39;s what they look like, for the China-competing group (got quotas) vs. the No-quota (non-competing) group. Not compelling.

Note that there seems to be differential trends pre-treatment. Patents in the "No quota" (non-china competing) group seemed to be falling before China joined the WTO. Secondly, patents in both groups are just falling to zero. This is not mentioned in the paper.

Given the above graph, how/why did BDvR find any effects? Well, another thing that bothered me on my initial read is that the authors switch between data sets for each robustness check. The initial table contains no sectoral FEs. (Had they included, their results vanish.)

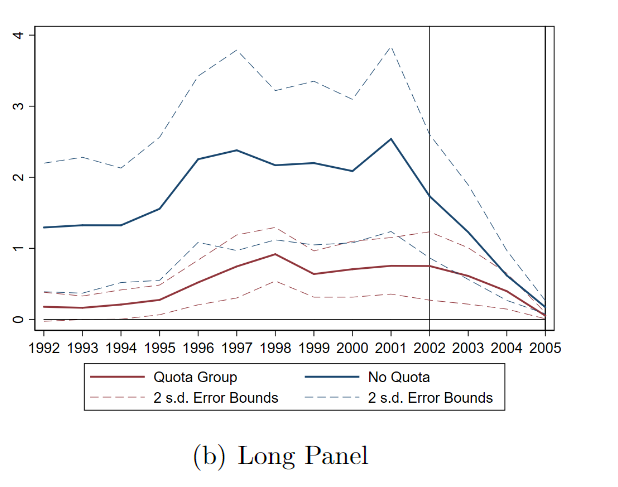

Thus, when BDvR include firm FEs, they switch to using a longer, different panel data set. When we plot the pre-treatment trends of that one, we get a different picture, but still with extreme tapering. We noted, even here, patents in both groups fell the same % from 2000 to 2005

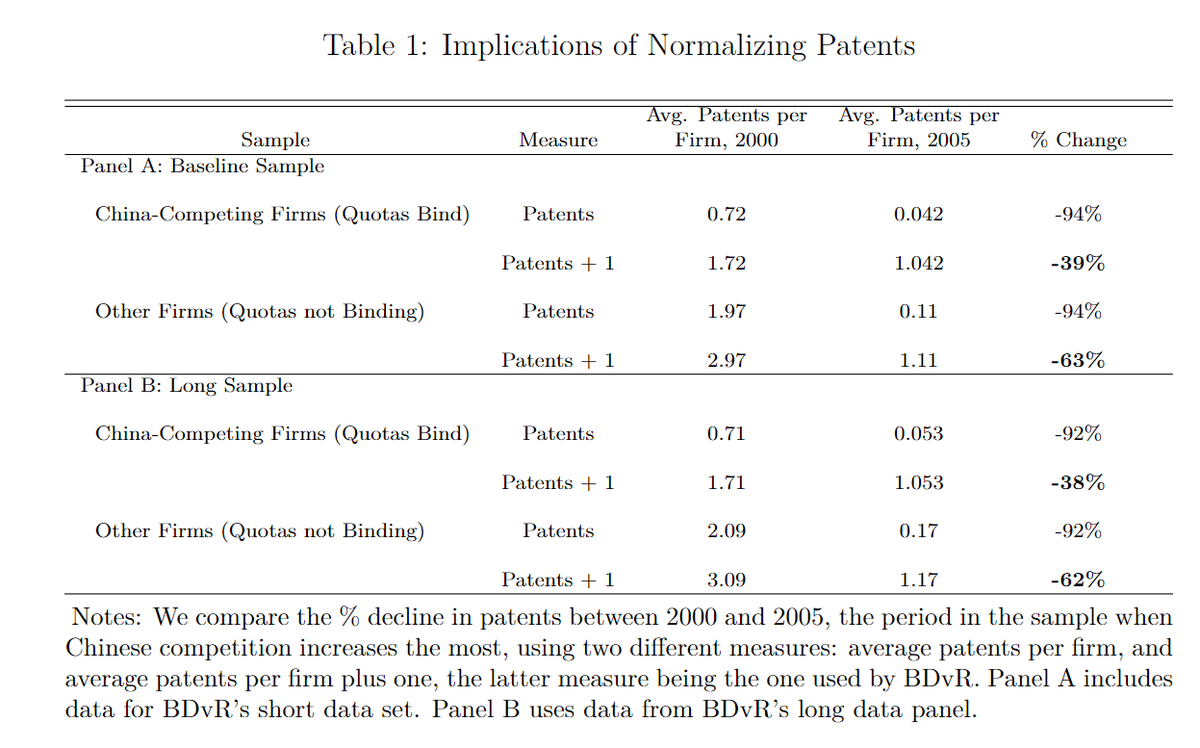

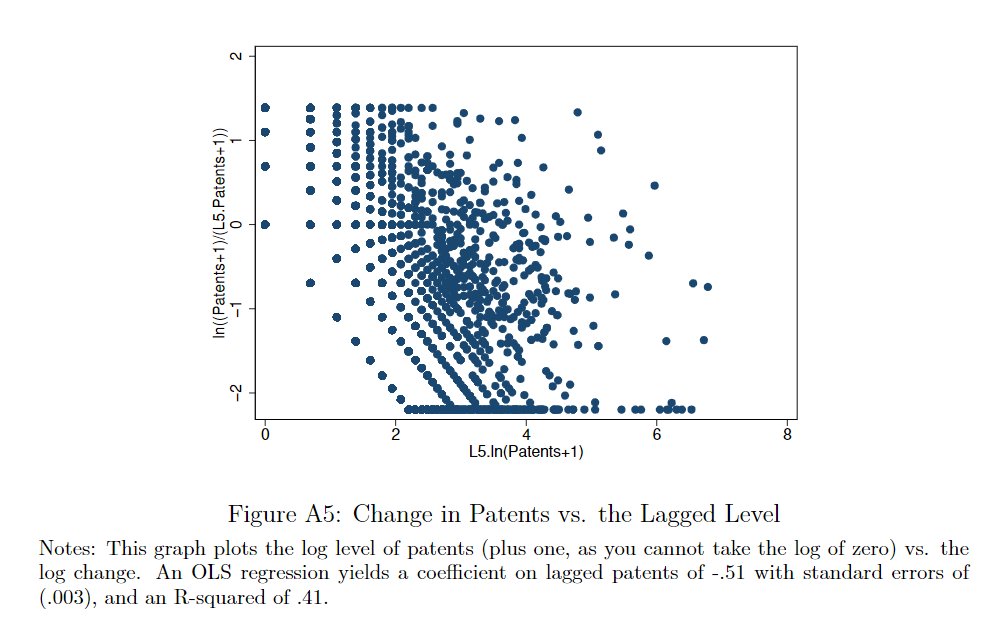

BDvR found a positive effect only b/c they normalize patents by adding one and taking logs. This transformation induces an obvious bias that will be larger for small numbers. The China-competing sectors had fewer patents to begin with, ergo a systematic larger bias.

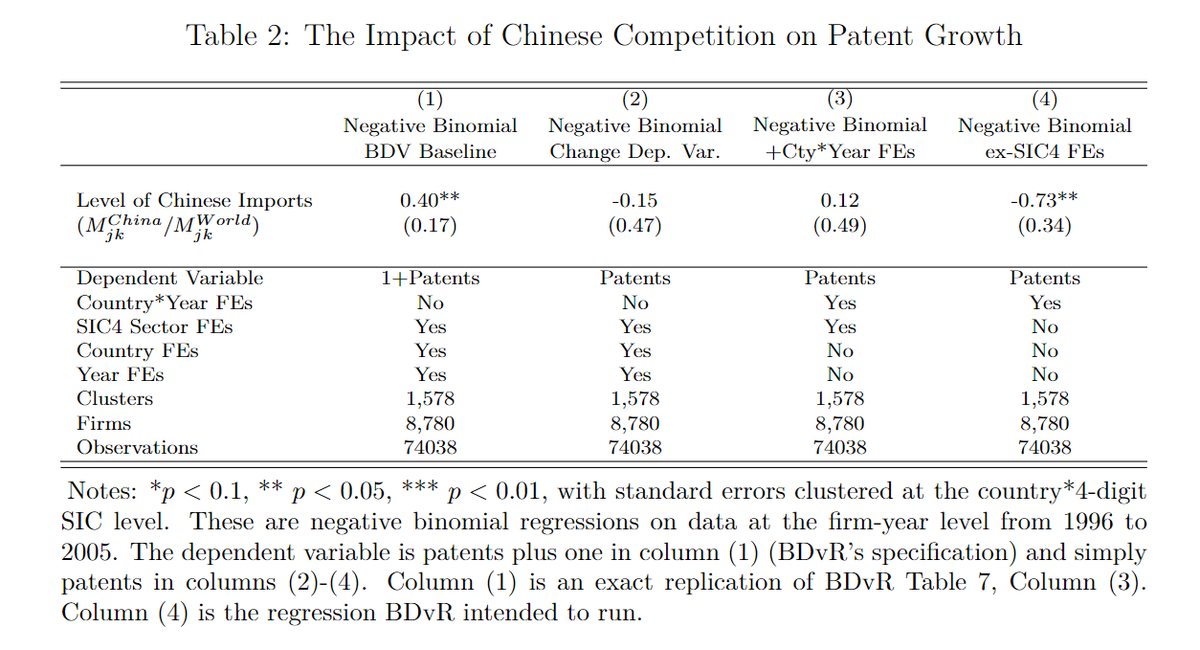

There was one regression in BDvR immune to this. The formulation using a negative binomial regression. However, we noticed that they continued to add one (inexplicably), and also included different FEs from what they reported. Fixing these errors (4), the results flip

Note that, in these regressions, there is no identification, and no controls for trends, so these are just correlation in any case, with no compelling reason to attach a causal explanation.

The final version was slimmed down, but we had found issues elsewhere in their paper (the IT & TFP parts too). In the long patent panel, we found no correlation between Chinese comp. and patent growth to begin with, with or without their firm FEs.

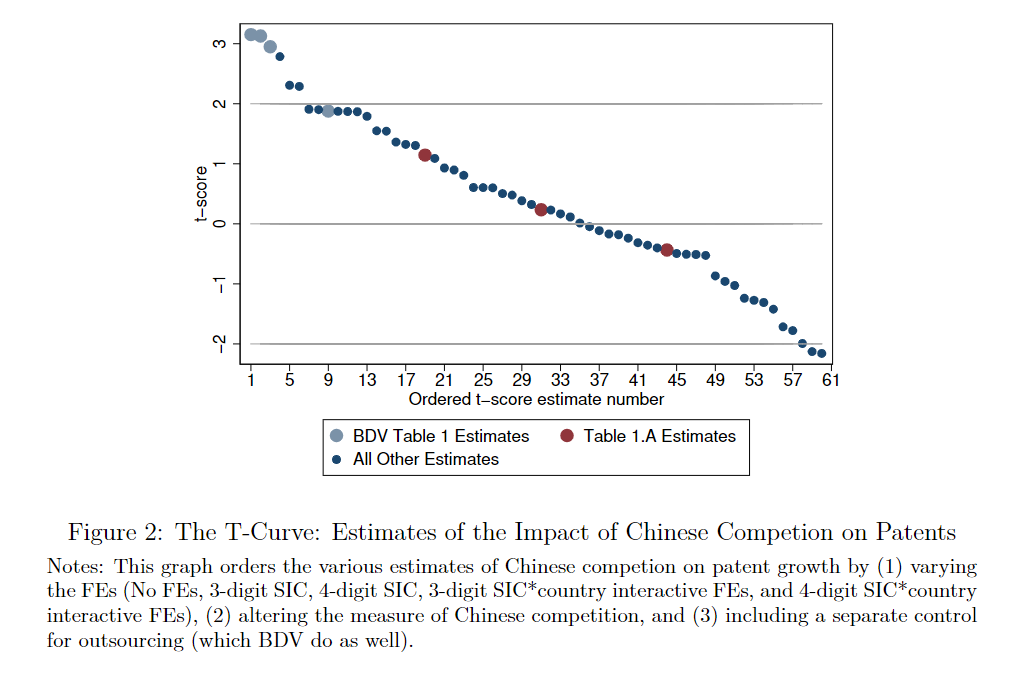

Running a number of different specifications, altering the FEs and measure of Chinese competition used, we found that most variations the authors could have run would have been insignificant aside from the ones they reported.

We also found the authors censored some of their data (log changes in patents). I& #39;m not sure if they reported that they did this, but they did not report that if they uncensor, some of their results become insignificant.

Overall, I think these (censoring, transforming vars, switching data sets) are helpful tricks to use for RAs or young scholars who coded up their data set, and can& #39;t get their magical significance stars. Grad students at top programs likely already get trained to do these things.

Also, in defense of the authors, I don& #39;t think there is anything unusual about this paper. This is how most empirical "research" is done in academic economics at the highest levels. While pointing it out is basically forbidden, it& #39;s an open secret.

It& #39;s very difficult to publish in a top 5. But, this case shows the way. 1. Adopt a very popular thesis -- free trade magically induces innovation! 2. Be a well-connected "star". 3. Feel free to "shoot a man on 5th avenue" in your analysis, you& #39;ll be accepted if 1 & 2.

Lastly, let me say a couple things about @RevEconStud. First, the editor we dealt with did a very professional job. Second, IMHO, it& #39;s a scandal that @RevEconStud does not accept comment papers unless there is a clear mistake (such as a coding error).

The coding errors, which could be proven, were the main reason we got published. According to @RevEconStud, just showing a paper is not robust to (even a large #) of various improvements in specification is not enough to publish a comment.

But, people should realize that, when they see an empirical paper in a top 5, it& #39;s an indication that the authors are well-connected, and the thesis is popular/politically convenient. It doesn& #39;t mean the analysis is correct. It may literally be chalk full of blatant errors.

Instead, a single paper published in a top 5 journal is often enough for tenure at most academic institutions. But, this top 5 fetish doesn& #39;t make much sense once you know how the sausage is made.

I was originally going to leave the BDvR paper be. But, two years ago NES had a top growth economist out from Harvard who prominently cited the BDvR paper in a lecture on growth to students. The paper now has 1181 citations on google scholar. Something had to be done.

So, what can be done to change the profession? Well, if you are refereeing an empirical paper, and the authors have not plotted any relevant data, reject it. Second, resolve to write at least one comment paper in your career.

Third, if you are an editor at a major journal, ask what you can do to encourage replication. For example, post a clear policy (hint hint, @RevEconStud). State that all comment papers will be given full consideration, & published with equal standing as original submissions.

Wow! This blew up. Let me add some more thoughts on replication. I could be wrong, but in my view, I think part of the problem is the culture in academic economics. Replication is not valued -- particularly by tenure committees.

The QJE, ECTA, and the JPE, in practice, rarely accept comment papers. (I& #39;ve shared my experience at the QJE before: https://statmodeling.stat.columbia.edu/2015/12/19/a-replication-in-economics-does-genetic-distance-to-the-us-predict-development/">https://statmodeling.stat.columbia.edu/2015/12/1... )

A newly p-hacked top 5 paper published with your well-connected advisor, for example, is extremely valuable. But a comment paper showing that a seminal paper is actually worth less than zero in the eyes of some.

Another thing referees should be aware of is that regressions results are easy to p-hack. Empirical papers should always display their key results graphically. In a diff-in-diff, it should be required to plot the pre-treatment trends (of the raw data).

Top journals, particularly journals like Econometrica, seems to have an affinity for very complicated kinds of analysis. Intricate mathematical models, etc. This is signalling. More respect needs to be paid to simple models, and simple scatter plots of the data.

Read the BDvR paper, and try to figure out how they arrived at their TFP estimates, or their estimates for the overall economy-wide impact of Chinese competition. You won& #39;t be able to do it. They used complexity, not to enlighten, but to confuse. http://douglaslcampbell.blogspot.com/2018/02/on-uses-and-abuses-of-economath.html">https://douglaslcampbell.blogspot.com/2018/02/o...

Be extra suspicious of "blockbuster" papers, where "big" guys find very large results. Ask: is the magnitude of this result plausible relative to the literature? If not, it& #39;s probably more likely that the finding is spurious.

As a referee, if you get a paper, and the authors find result X, and concede it is sensitive to controlling for Y, don& #39;t automatically reject the paper b/c the results are "weak".

Journals requiring data and code has been a huge step in the right direction. I think it might be a good idea for journals to consider requiring data and code with the submission. This forces authors go back and clean up their codes.

Probably, top journals should think about commissioning people to check robustness. (But, before they do that, they should of course all start allowing comment papers, even when there is no coding error...)

Lastly, since this thread blew up, I& #39;ll share another thread on some of my other recent research not on replication (it& #39;s on the collapse in US manufacturing...) https://twitter.com/tradeandmoney/status/1257709625727647746">https://twitter.com/tradeandm...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter