About 25 years ago, I studied lynching & cultural representations of and memory of lynching, & later memory of Reconstruction, including monuments. http://bruceebaker.com/articles.htm ">https://bruceebaker.com/articles.... & https://www.bloomsbury.com/us/this-mob-will-surely-take-my-life-9781847252388/">https://www.bloomsbury.com/us/this-m...

2/24

2/24

My interests have moved on, & I’m not as up to speed as I could be on all the great recent scholarship on lynching. Check this state-of-the-field from 2014 by @MichaelPfeifer7: https://doi.org/10.1093/jahist/jau640

3/24">https://doi.org/10.1093/j...

3/24">https://doi.org/10.1093/j...

I’m also no expert on Confederate monuments, but these folks are: @SassyProf @HilaryGreen77 @AdamHDomby @KevinLevin

4/24

4/24

What does this mean? We could ask the participants, but that gets us into the intentional fallacy. Quite apart from what the people intended, the event has meanings due to how it fits with culture & history.

5/24

5/24

Two aspects to this, lynching & Confederate monuments, then we’ll bring them together. Let’s start with lynchings & how their meaning are created.

6/24

6/24

Christopher Waldrep ( https://www.palgrave.com/gp/book/9780312293994)">https://www.palgrave.com/gp/book/9... argued that lynchings were about drawing boundaries: the people of a community declaring they had the right to decide what happened to people in their community.

7/24

7/24

Opponents argued that a lynching was not just the business of the local community; it was everyone’s business. Big argument here over national jurisdiction & rights. Using narratives about meaning of lynching was part of this debate.

8/24

8/24

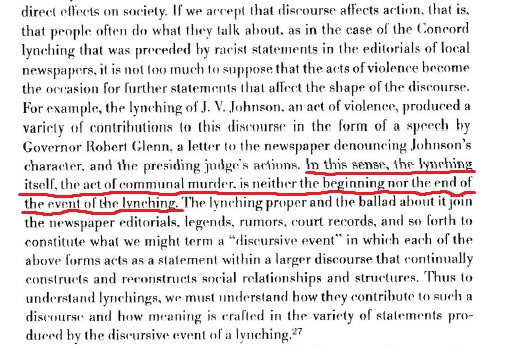

My initial interest was in ballads about lynchings in NC & how they operated in this debate. I argued they were part of a broader discourse about lynching, that representations of lynching had effects that continued the messages of the event itself.

9/24

9/24

By the early 20th c., a more widespread form of this was the photograph. See the work of Amy Wood on lynching as spectacle & photographs of lynching: https://uncpress.org/book/9780807871973/lynching-and-spectacle/">https://uncpress.org/book/9780...

10/ 24

10/ 24

These photos often circulated as postcards, though eventually the Postmaster General banned them, around the time of the 1906 lynching in Salisbury, NC, that @ClaudeClegg wrote about in https://www.press.uillinois.edu/books/catalog/47krp5by9780252035883.html

11/24">https://www.press.uillinois.edu/books/cat...

11/24">https://www.press.uillinois.edu/books/cat...

The photos also circulated in communities: I was handed copies of photos of one lynching in NC and one in SC in the mid-1990s. These images were powerful & continued to shape narratives about lynchings for decades.

12/24

12/24

Now for the monuments. I won’t say much here since there are so many others saying better stuff than I can, but I like the work of Kirk Savage here: https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691183152/standing-soldiers-kneeling-slaves

13/24">https://press.princeton.edu/books/pap...

13/24">https://press.princeton.edu/books/pap...

Fundraising campaigns for Confederate monuments liked many, small donations as a way of demonstrating popular (white) support & legitimacy, a way of suppressing dissent. Monument represents community values, or pretends to.

14/24

14/24

Lynching was often directly tied to politics, as was the placing of Confederate monuments. One example: in 1898, a white girl near Concord, NC, was murdered & Joe Kizer & Tom Johnson were lynched: http://lynching.web.unc.edu/dhp-markers/joe-kizer-2/">https://lynching.web.unc.edu/dhp-marke...

15/24

15/24

This happened in the middle of the 1898 election campaign where white supremacist Democrats used racial hatred to depose a biracial political alliance. Newspaper articles about the lynching directly linked the two.

16/24

16/24

The Wilmington Massacre & coup d’état in 1898 was also part of this & you should read about that: https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2017/08/wilmington-massacre/536457/

17/24">https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/...

17/24">https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/...

Back to Raleigh. Kirk Fuoss discusses “lynching performances” as “theatres of violence,” ( https://doi.org/10.1080/10462939909366245).">https://doi.org/10.1080/1... Performances with an audience. Recent attacks on monuments to white supremacy are performative (Austin, Bauman, etc.).

18/24

18/24

My proposition: here is a biracial mob attacking a symbol of white supremacy & doing two things at once very powerfully.

19/24

19/24

First, they are attacking the notion that the community supports this symbol of white supremacy (undermining the legitimacy of the NC monument-protection legislation & the legislature that passed it).

20/24

20/24

Second, appropriating a cultural form (lynching performance) that was the most powerful support for white supremacy & turning it against white supremacy.

21/24

21/24

Also, can we remind ourselves that what is being attacked here is a hunk of metal, a dead symbol of a dead order, not a living human being, a man and a brother?

22/24

22/24

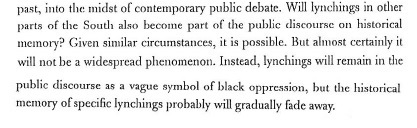

So, a bit tricky to sketch out complex ideas in this medium, but hopefully it’s worth thinking about.

23/24

23/24

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter