I am reading Ahmed El Shamsy’s recent book on the impact of #printing on modern discourses on #Islamic scholarship. Like his previous book, it is extremely readable and insightful. I will post some questions and intriguing passages from the chapters that interest me most./1

In the introduction, the author tells us that he will cover the 19th c. which saw the marginalisation of the classical Islamic work, the adoption of printing & rebirth of the classical heritage. Muslim reformers reasserted the classical tradition to undermine the postclassical./2

I think ch. 1 will be the most interesting for me: it names two key factors in the marginalisation of the classical works: "the dramatic decline of traditional libraries and the voracious appetites and deep pockets of European collectors of Arabic books."(p.6)/3

It seems ch. 2 is even more interesting. EL Shamsy yet identifies two other enemies of the classical Arab-Islamic works: "scholasticism of postclassical academic discourse" and "Sufi esotericism." No, ch. 2 will definitely be more fun.

To be sure, the author warns the readers to take the labels he uses in the book as "descriptive" rather than "evaluative." Very fair warning. Shukran. Frankly, this thread will not do justice to the book but I will post a few more ideas from the chapters./4

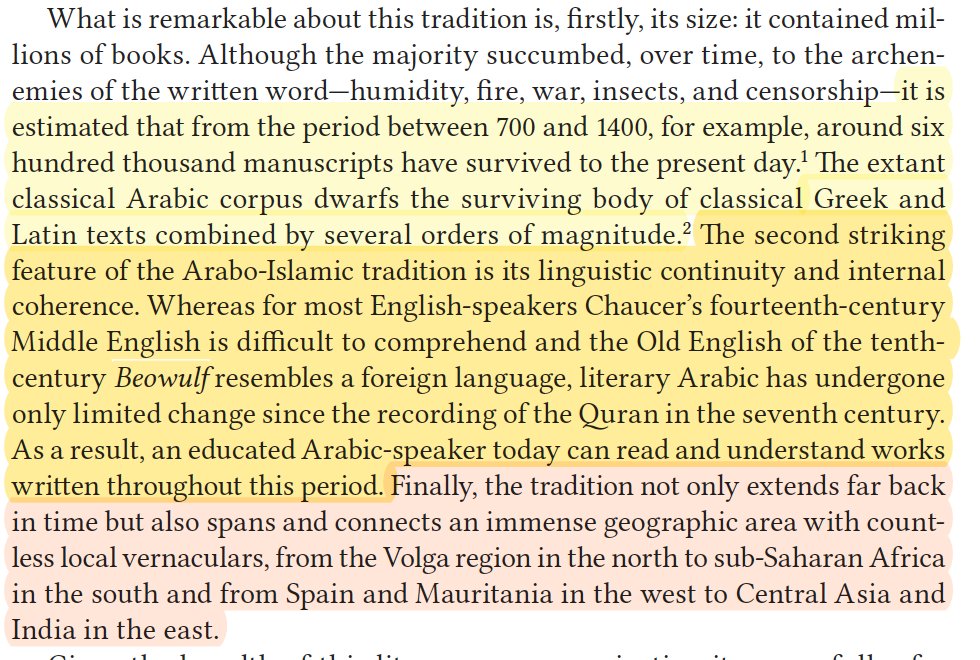

Ch. 1. "The Disappearing Books" begins with a definition of the Arab-Islamic literary tradition. What is remarkable about it? Consider this: (p.8) /5

We will have to see how is this argument different from the idea of post-classical decadence, Islamic "golden age," the brilliant classical period destroyed by the Mongols and/or Islamic dogmatism something Muslim "apologists" and early Orientaliststs agreed with each other?/6

Important footnote from p.8 cited above. Check out the open-access @Open_ITI - the largest repository of machine-readable classical Arabic texts. /7

Egyptians were aware of the disappearance of books. So were the European collectors who competed with each other over Arabic manuscript heritage. But the Orientalist narrative blamed the dearth of books in the Middle East on cataclysms and wars, such as the Mongol attack. /8

"[The prominent Orientalist Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall

had asked Seetzen to look for a copy of the famous tenth-century "Kitāb al-Aghānī", but Seetzen was told by an Egyptian scholar that not a single copy of the work survived in Egypt. The French had taken the last one.]" https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🥸" title="Disguised face" aria-label="Emoji: Disguised face"> /9

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🥸" title="Disguised face" aria-label="Emoji: Disguised face"> /9

had asked Seetzen to look for a copy of the famous tenth-century "Kitāb al-Aghānī", but Seetzen was told by an Egyptian scholar that not a single copy of the work survived in Egypt. The French had taken the last one.]"

The description of the #looting of #Arabic, #Persian and #Turkish manuscripts is quite painful. Thousands of them made it to the BL or BnF. Orientalists and "hobby" orientalists were responsible for "obtaining" thousands of manuscripts. They often sold them in Europe.../10

At first, these Muslims were puzzled: Why are these guys collecting all of our books, what do they wanna do with them. The older notion of Oriental wisdom was no longer sustainable. There was no more mystery, the Orient was plainly declared as inferior. p. /12

Instead "the collectors sought Oriental books as the raw material for the construction of a taxidermic replica, a stuffed corpse of the Islamic cultural edifice to be placed in the mental museum of European thought." p. 16. Yep.

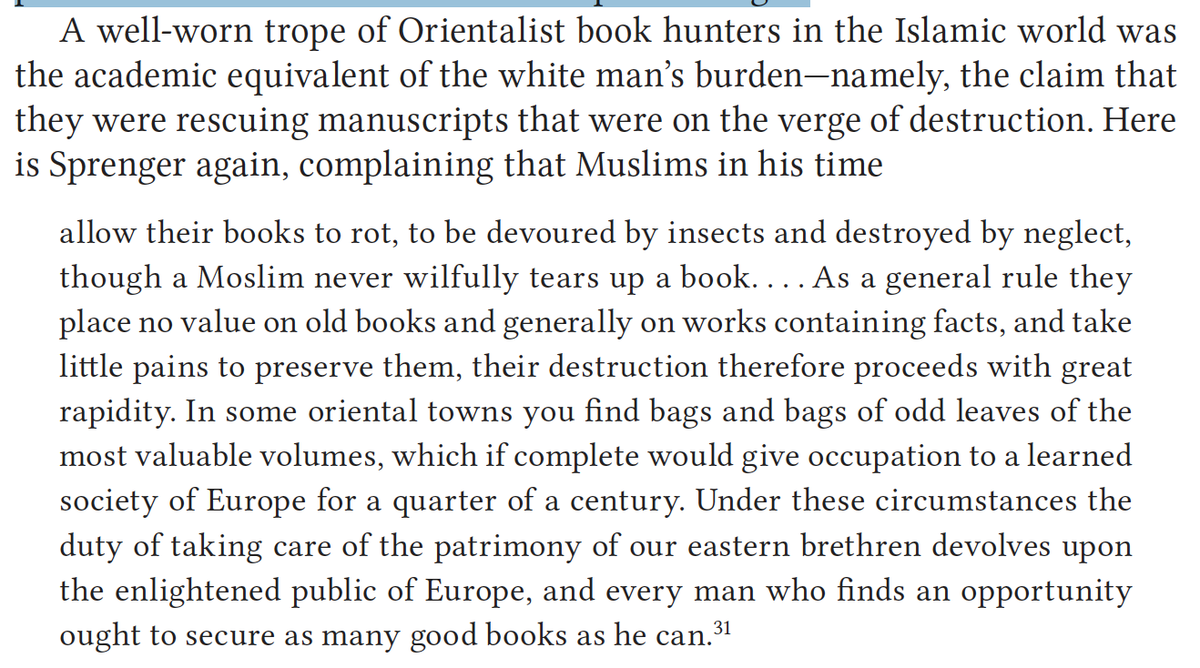

Book hunting as "white man& #39;s burden" /18

"Jean-Joseph Marcel recounted heroically saving Arabic manuscripts from the fire ravaging the Azhar mosque after his fellow French soldiers had shelled it and rescuing the Quranic parchment in Fustat from neglect and humidity.../19

...—even though it had survived in the same location for probably more than a thousand years." p. 17. The theme of rescuing is prevalent even though there was more stealing. But the majority was sold willingly - concedes El Shamsy - if not legally. /20

El Shamsy& #39;s account of the "grave-robber mentality of some Orientalist book buyers" is quite damning. Yet, he lists another reason for the depletion of books from ME libraries: the decline of traditional institutions of book culture. /21

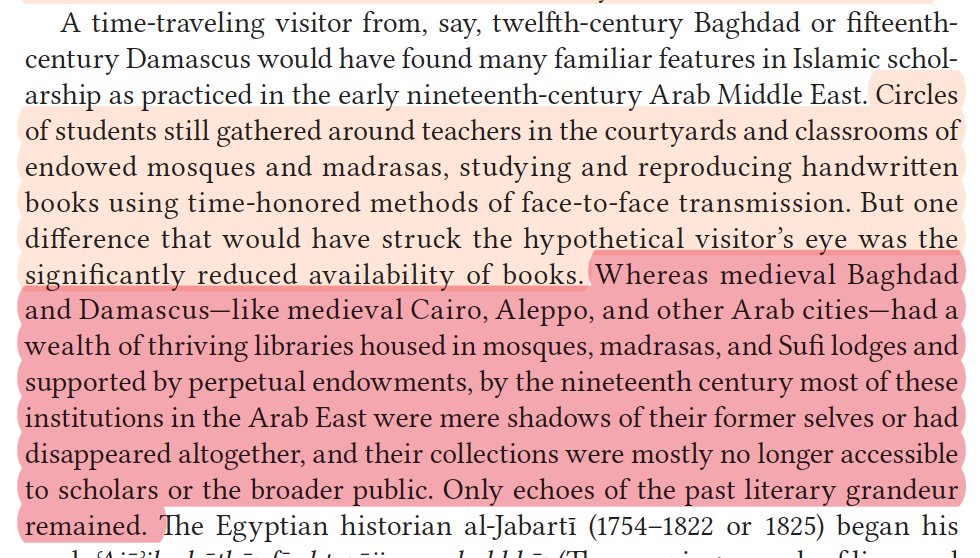

Specifically the decline of the madrasa and other institutions of learning. For instance, from 70 madrasas in Cairo listed by al-Maqrizi (d.1442) only al-Azhar retained its position as a teaching institution by mid 19th c. The rest were reduced to a place of prayer. (p. 20). /22

What caused this? The Ottomans conquest of Egypt and Syria (CE 1517), following which Cairo and Damascus, the centres of Arab culture, were downgraded to the provincial capital, which also led to a brain drain from the region to Istanbul. No high profile patronage./23

Also, El-Shamsy notes that the language of administration of the three great Muslim Empires of the time, #Ottomans, #Safavids and #Mughals was #Turkish and #Persian. Not good for #Arabic written culture, obv. Even Arabs wrote in Ajami languages. This never happened before./23

Okey, the Ottomans too had looted the libraries during their conquest of the region. Who knows what proportion of the manuscripts in Istanbul libraries was obtained as booty? Who knows. /24

El Shamsy gives some numbers. We have to make some guesses: Currently, Süleymaniye Library holds 90,000 Arabic mss, Egyptian National Lib holds 60,000. Overall, Turkish collections hold much more Arabic mss than Egyptians. In this case, the isolated Yemen fared better. /25

Thus, according to El Shamsy, Arab societies lost their literary heritage first to the Ottomans, then to Europeans. In both cases, the physical removal of the books made them unavailable for Islamic scholarship. Until the creation of modern libraries. This was chapter 1.

But, as I mentioned above, apart from the physical loss of the books, El Shamsy identifies two other intellectual factors that marginalised the classical Islamic literature, namely "scholasticism" and "esotericism". He deals with this in chapter 2. /27

CHAPTER 2. POSTCLASSICAL BOOK CULTURE

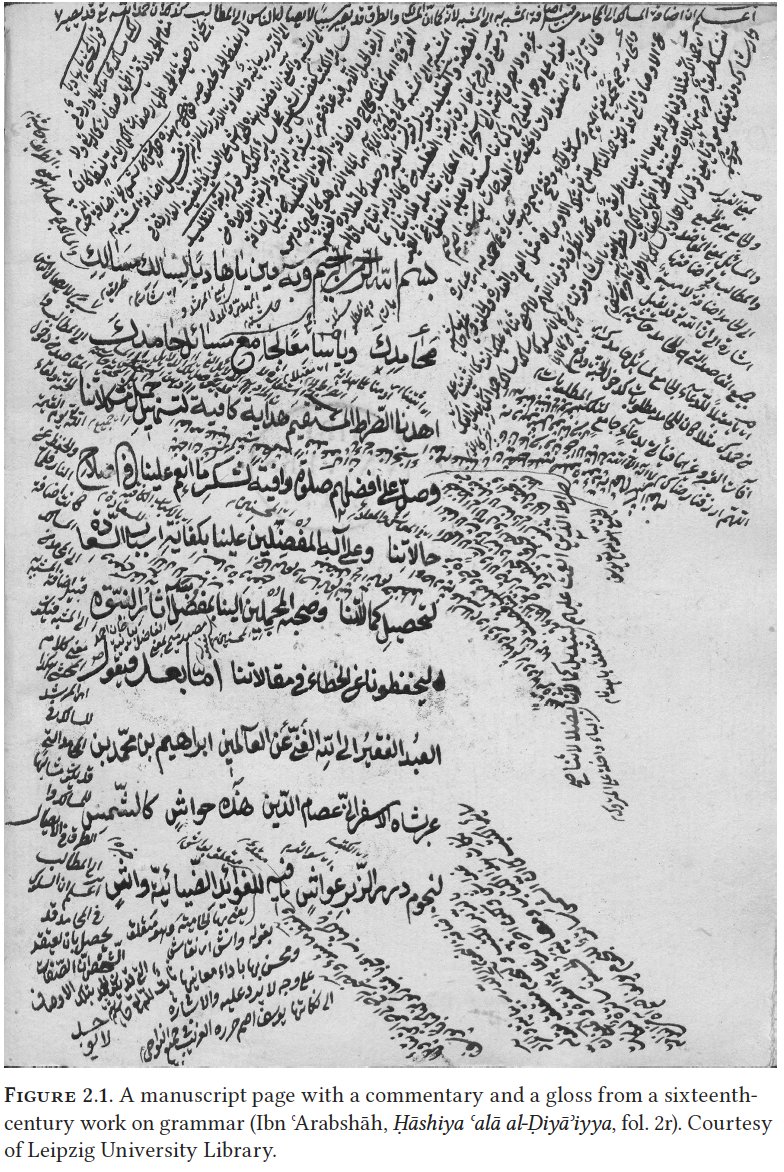

El Shamsy begins with an assessment of the Islamic curriculum and scholarship in the postclassical period (16-19th c). We find out that the curriculum was limited to introductory textbooks, commentaries and glosses on other texts. /28

El Shamsy begins with an assessment of the Islamic curriculum and scholarship in the postclassical period (16-19th c). We find out that the curriculum was limited to introductory textbooks, commentaries and glosses on other texts. /28

These commentaries and glosses literally buried the texts on which they were written. The content of the texts was neglected, instead, the shaykhs guided the students to master formal aspects of a given text, namely language and rhetoric. Based on earlier commentators, ofc /29

So, lexicography, rhetoric and Aristotelian logic are part of every "postclassical scholastic& #39;s" toolbox. They used these to analyse the works of the last great "mujtahids" but never went beyond them. It seems the "closure of the door of ijtihad" was taken seriously. /30

A typical gloss (hashiya). This is the laborious and time-consuming endeavour. It hindered engagement with the actual content - agrees Ahmed El Shamsy with Muslim modernists. The type of creativity that was appreciated was also mostly focused on form and style (ie. badiʿiyya) /31

Why didn& #39;t postclassical scholastics engage with the classical texts? Where did this textual traditionalism come from? The structure of Sunni legal authority is to blame (closure of the door of ijtihad). Or lack of access to classical books. Or both. /32

Both mutually contributed to each other suggests El Shamsy. I tend to agree but there is a lot to rethink. I don& #39;t know about about the postclassical period. One has to compare the situation with Safavid Iran to see if Sunni scholasticism should be blamed at all, I guess? /33

Next, the author turns to discuss the other foe of Arabic book culture – ESOTERICISM.

Mystics destroying their books upon choosing the esoteric path is a classical trope. #Rumi is said to have done that among others. But did esotericism helped the decline of book culture? /34

Mystics destroying their books upon choosing the esoteric path is a classical trope. #Rumi is said to have done that among others. But did esotericism helped the decline of book culture? /34

Also, let& #39;s not forget that the contribution of esotericism to the alleged decline of the Muslim world is not a new idea. /35

El Shamsy narrows it down to Neo-Platonic esotericism of Ibn Arabi (or rather esoteric Neo-platonism?), which apparently successfully undermines individual reasoning and learning though instruction. /36

So, if real knowledge is to be obtained only through divine intervention and unveiling then why bother? Makes sense. Very discouraging for study-minded folks though. /37

But the idea of an illiterate divinely inspired muse - saint was already there in the classical period (remember Shams-i Tabrizi) and didn& #39;t lead to abandoning books. So what is special about the postclassical period? /38

Reading through I have been sceptical about this argument. Yes, Sufis had their own epistemology, but that was limited to their small circles. El Shamsy obviously anticipates this and argues that the impact was much wider. Eg. the disintegration of hadith scholarship. /39

In the field of law, too, esotericists such as al-Shaʿrānī and Shāh Walī Allāh distorted the nature of Islamic law, which was was formed by the intellectual activities of the great jurists, attributing their achievement to divine inspiration. Yeah, this is not cool at all. /40

Esotericism likewise penetrated other fields such as theology, and even grammar. Occult sciences and lettrism were now welcomed to the mainstream under the guise of esotericism (a bad thing). All these marginalised rational pursuits that characterised the classical age. /41

But there were also pushbacks against esotericism which sought to establish connection with classical works: people look for Sibawayhi& #39;s book, the works of Ibn Taymiyya and Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya resurface. /42

So, we are reaching the end of the chapter 2 and we have been wondering where does Ahmed El Shamsy& #39;s thesis stand in relation to the the narrative of decline? Luckily, he clarifies his position vis-a-vis the modernists. Here is what he says which makes sense in my opinion. /43

These two chapters dealt mainly with the pre-print book culture, but the actual subject matter of the book is the impact of print culture on Islamic scholarship. I will stop here, but highly recommend the book to anyone interested in the #Islamicate world. Shukran. /End.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter