Dear Twitter, I have spent a lot of time in the past two years working on this thing called my & #39;dissertation.& #39;

What is Christopher doing, you may wonder?

In this thread I will explain my dissertation:

What is Christopher doing, you may wonder?

In this thread I will explain my dissertation:

My dissertation is titled "Power and Elite Competition in the Neo-Assyrian Empire, 745-612 BC." I am examining the careers of the officials who made the Assyrian empire run.

We have a fantastic and very unique source base for this type of study.

We have a fantastic and very unique source base for this type of study.

When successive British expeditions excavated Nineveh, they uncovered tens of thousands of cuneiform tablets. Among them were famous literary texts from the Library of Ashurbanipal like the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Atrahasis Epic.

Others were less sensational, like administrative lists of goods being distributed from palaces (think ancient spreadsheets). But there were also several thousand official letters, sent between the king and provincial governors.

This makes for a source base unparalleled in the ancient world. We have thousands of documents of official communication, all from the imperial capital. Nowhere else has anything like this.

Rome? Our main collection of official letters are those between Pliny the Younger and Trajan. Only 121 letters, between one emperor and one governor, and they survive because they were edited in ancient times for publication, presumably selectively.

Egypt? Only 382 letters were found at el-Amarna, a substantial number to be sure, but we have 3,859 letters from Assyria between 745-612 – 10x as many! (although spread out over a longer period of time)

Until now, most scholarship of Near Eastern imperial organization has been deeply positivistic and Weberian (and occasionally Marxist). This tweet was a joke but also it’s real: https://twitter.com/cwjones89/status/1270431277242605568?s=20">https://twitter.com/cwjones89...

Studies of Assyrian officials have generally proceeded by taking a name for an office in Akkadian, the language of ancient Assyria, and trying to explain the range of duties performed, what functions they oversaw, who appointed them, and who they answered to.

This assumes that Assyrian bureaucracy worked like a modern hierarchical organization.

In fact, many officials with different titles seem to do the exact same duties. People bypass their alleged bosses to write directly to the king.

In fact, many officials with different titles seem to do the exact same duties. People bypass their alleged bosses to write directly to the king.

It’s time to bring in some new methods.

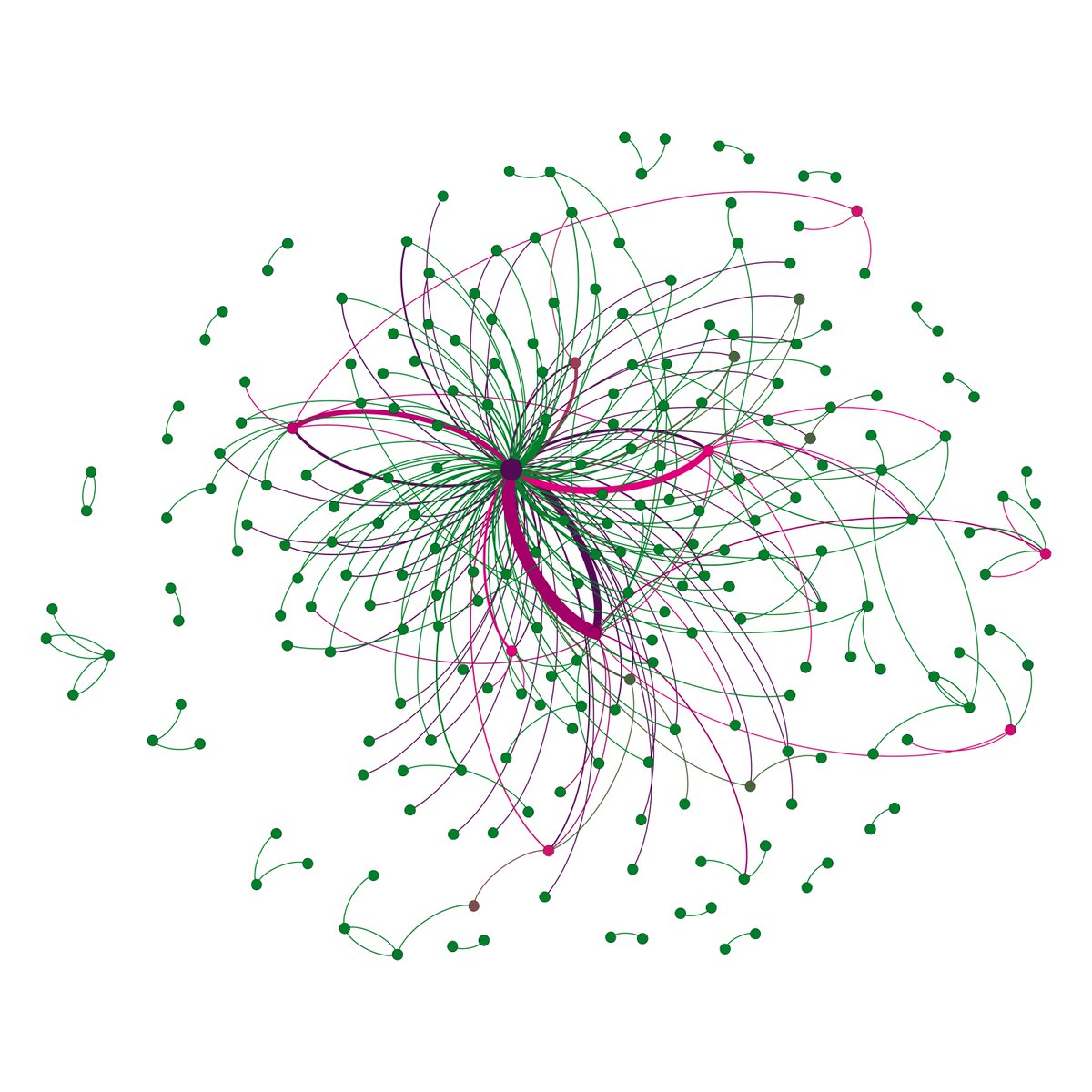

The number of letters allows us to use methods we can’t use to study other ancient empires. For my dissertation, I am applying tools of social network analysis (SNA).

The number of letters allows us to use methods we can’t use to study other ancient empires. For my dissertation, I am applying tools of social network analysis (SNA).

SNA looks at who can communicate with whom. But it’s not fundamentally about organization – it’s about relationships. Who talks to whom, and more importantly, who is well connected?

There is a classic SNA paper by Mark Granovetter called “The Strength of Weak Ties.” He surveyed thousands of new hires about how they found jobs. Most of them learned about the job not from a close friend but from someone they didn’t know all that well.

Think about someone who has opened a professional door for you. Did you know them well? Were you close?

Maybe, but most likely you weren& #39;t. Maybe you met them at a conference, or at a party, or even on Twitter.

Often it& #39;s the people we don& #39;t know all that well who connect us.

Maybe, but most likely you weren& #39;t. Maybe you met them at a conference, or at a party, or even on Twitter.

Often it& #39;s the people we don& #39;t know all that well who connect us.

Why is that? It& #39;s about networks.

Those people connect us because they are a bridge connecting different groups of people who wouldn’t otherwise talk.

You and your friends are a network, and someone looking to collaborate with you is another network.

Those people connect us because they are a bridge connecting different groups of people who wouldn’t otherwise talk.

You and your friends are a network, and someone looking to collaborate with you is another network.

One person may happen to know people in both networks. Not well, but enough to know that one group has needs the other can fill, and vice versa.

Controlling access between those groups gives that person power.

Controlling access between those groups gives that person power.

The same was true in Assyria. Who could connect you to powerful people? Power comes through controlling access.

What about the king? Despite his mighty self-presentation, the king is a prisoner of information. He can’t be everywhere at once – He only knows what people tell him.

What about the king? Despite his mighty self-presentation, the king is a prisoner of information. He can’t be everywhere at once – He only knows what people tell him.

Kings have ways to try and get around this limitation, but it’s always a problem. He sits at the center of a world where every official tells the king that everything is going great and anything that’s not great is someone else’s fault.

Competition between officials for the king’s favor is cutthroat. Since everyone is trying to make themselves look good, one way to stand out is to make everyone else look bad.

Assyrian officials are constantly denouncing each other for alleged crimes: Theft, corruption, robbery, murder, tax evasion, bribery, cruelty, blasphemy. You name it.

We have no way of knowing how much of this was true, but it’s out there.

We have no way of knowing how much of this was true, but it’s out there.

Why such a vicious competition for status? Because status gets you perks, but perks are not given to everyone.

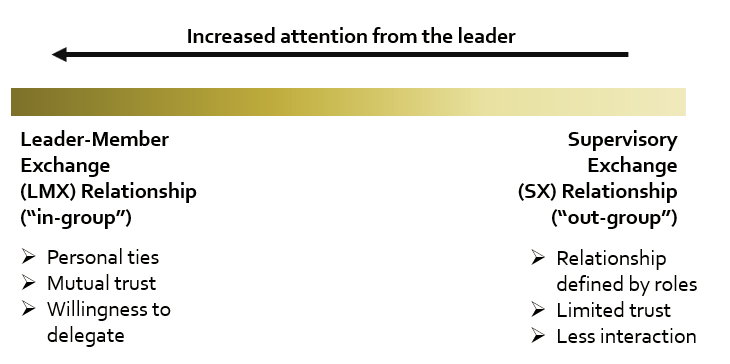

Enter another theory, something you usually find taught in business schools: Leader-Member Exchange Theory (LMX).

Enter another theory, something you usually find taught in business schools: Leader-Member Exchange Theory (LMX).

LMX theory argues that superiors can only spend so much energy on subordinates, so they prioritize. They invest in the subordinates who they think are most competent or they like the best. The rest get less attention.

Sound familiar to anyone’s work or classroom experiences? OK.

Sound familiar to anyone’s work or classroom experiences? OK.

The result is that superior-subordinate relationships can be placed on a spectrum from LMX relationships on one end to “Supervisory Exchange” or SX relationships on the other.

If we can identify the officials with LMX relationships with the king, and high network centrality, we can find who the real power brokers are within the empire.

Hint: It& #39;s not always who you would expect.

Hint: It& #39;s not always who you would expect.

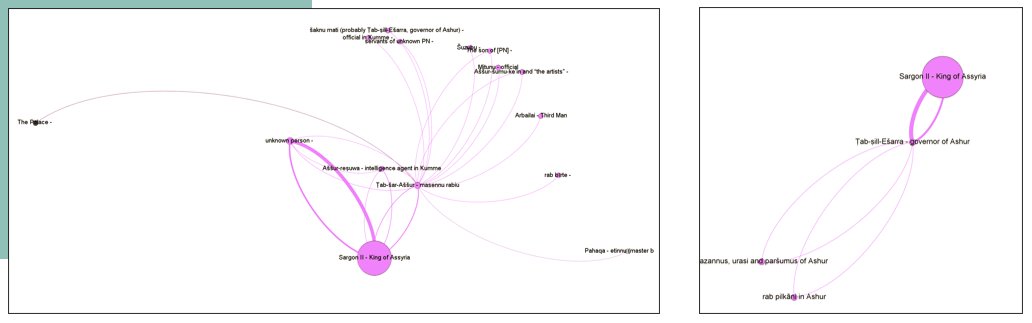

There are two officials who served under Sargon II (ruled 722-705) named Ṭab-šar-Aššur and Ṭab-ṣil-Ešarra.

They are our two most prolific writers under Sargon II, sending 35 and 34 messages to the king, respectively.

They are our two most prolific writers under Sargon II, sending 35 and 34 messages to the king, respectively.

Ṭab-šar-Aššur was the masennu rabiu ("treasurer")

Ṭab-ṣil-Ešarra was the governor of Assyria& #39;s ancient capital of Ashur, which contained Assyria& #39;s most important temple.

Each of them had a year of the Assyrian calendar named after them, in 717 and 716 BC, respectively.

Ṭab-ṣil-Ešarra was the governor of Assyria& #39;s ancient capital of Ashur, which contained Assyria& #39;s most important temple.

Each of them had a year of the Assyrian calendar named after them, in 717 and 716 BC, respectively.

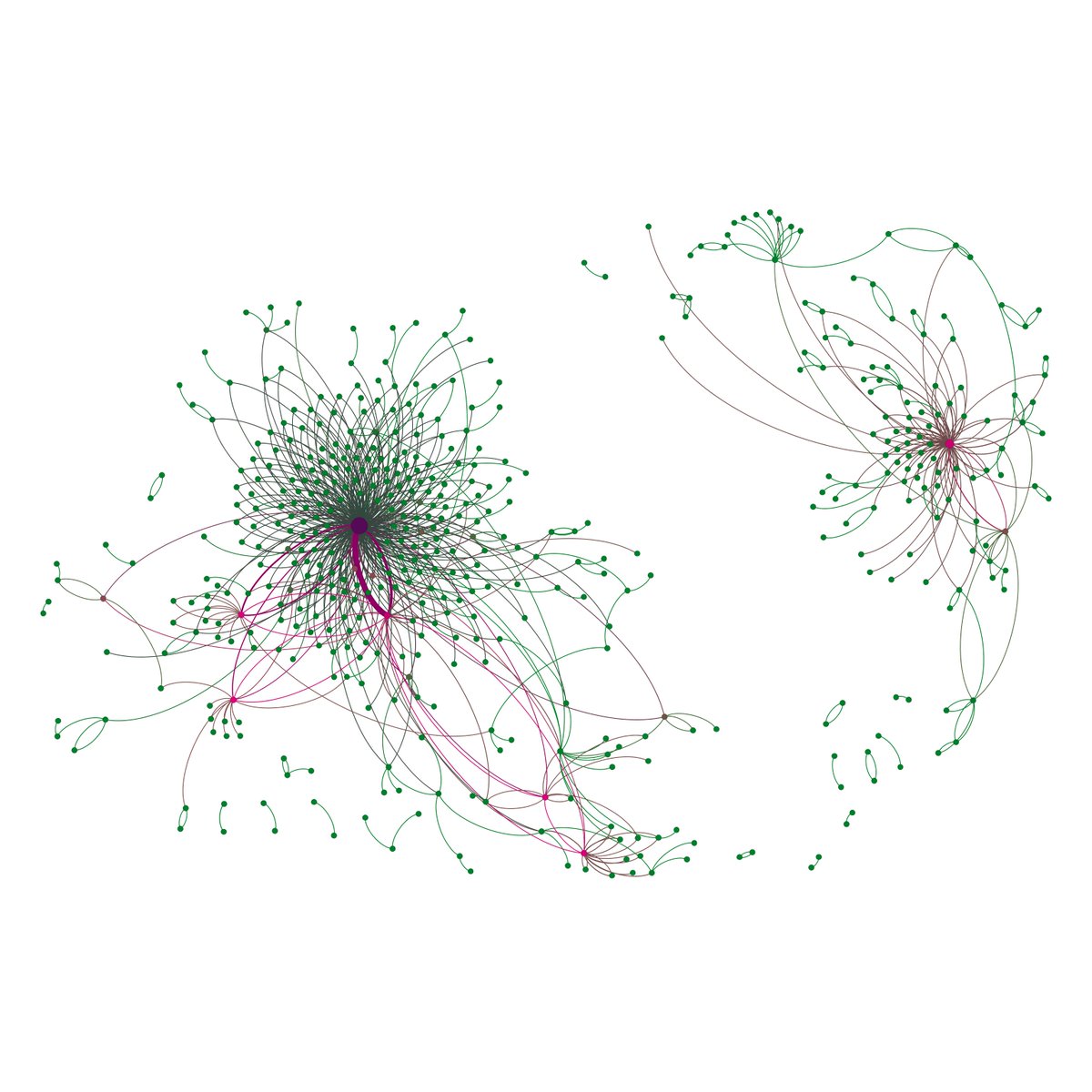

Now look at their networks. Ṭab-šar-Aššur is on the left. Ṭab-ṣil-Ešarra is on the right.

Looks pretty different, right?

Many people connect to the king through Ṭab-šar-Aššur. Almost no one does through Ṭab-ṣil-Ešarra. Why?

Because they don& #39;t see him as having influence.

Looks pretty different, right?

Many people connect to the king through Ṭab-šar-Aššur. Almost no one does through Ṭab-ṣil-Ešarra. Why?

Because they don& #39;t see him as having influence.

Assyriologists have longed assumed that both of these officials were powerful men of high status, due to their offices and the corresponding honors they received.

SNA and LMX tell a different story.

SNA and LMX tell a different story.

Ṭab-šar-Aššur had an LMX relationship with Sargon II. Ṭab-ṣil-Ešarra had an SX relationship.

So what difference does this make? How does this sort of thing enhance our understanding of the Assyrian empire?

Stay tuned tomorrow for a second thread!

Stay tuned tomorrow for a second thread!

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter