In honor of Juneteenth, a brief story about the America that almost was.

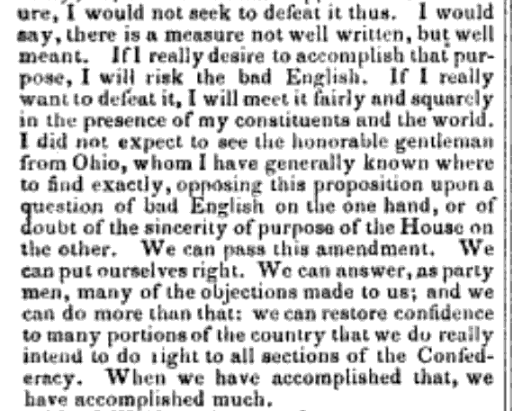

I was at the Federal Archives once, searching for a very different document, when I came across a stack of papers titled "Joint Resolutions Proposing Amendments to the Constitution of the United States."

I was at the Federal Archives once, searching for a very different document, when I came across a stack of papers titled "Joint Resolutions Proposing Amendments to the Constitution of the United States."

The words "Article 13" were underlined on the page below.

"Oh wow," I thought. "An original draft resolution for the 13th Amendment." I was kind of surprised they had just left it lying around with a bunch of totally unrelated documents.

Then I kept reading.

"Oh wow," I thought. "An original draft resolution for the 13th Amendment." I was kind of surprised they had just left it lying around with a bunch of totally unrelated documents.

Then I kept reading.

"Article 13. The right of property in the labor of any person lawfully held to service in the States [ ], ... shall not be abolished or impaired by Congress[ ]; and the United States shall protect all rights of property wherever federal jurisdiction extends."

It was the original 13th Amendment, introduced in January of 1861.

A version of it was passed by both the House and Senate by a two-thirds vote. It was signed by President Buchanan, and the states began to ratify it. Then it stalled out, due to the whole Civil War thing.

A version of it was passed by both the House and Senate by a two-thirds vote. It was signed by President Buchanan, and the states began to ratify it. Then it stalled out, due to the whole Civil War thing.

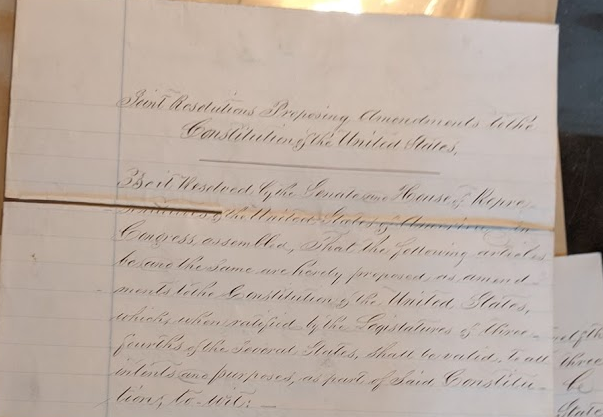

The Amendments That Almost Were did not get better from there.

The 14th Amendment: "The power to regulate commerce ... shall not be construed to authorize Congress to make any law impairing the right of the Master to remove from one State to another persons held to service[.]"

The 14th Amendment: "The power to regulate commerce ... shall not be construed to authorize Congress to make any law impairing the right of the Master to remove from one State to another persons held to service[.]"

Congress drafted these amendments in order to preserve what they believed were important Constitutional rights — through these amendments, they would ensure that Americans "shall not be deprived of the right of property in the service or labor of any person."

The would-be 16th Amendment would have imposed harsh penalties on any state interfering with slavery: "If any state shall enact ... any law impairing [the Fugitive Slave Act] such state shall not be entitled to any representation in Congress [ ] until the the repeal of such law."

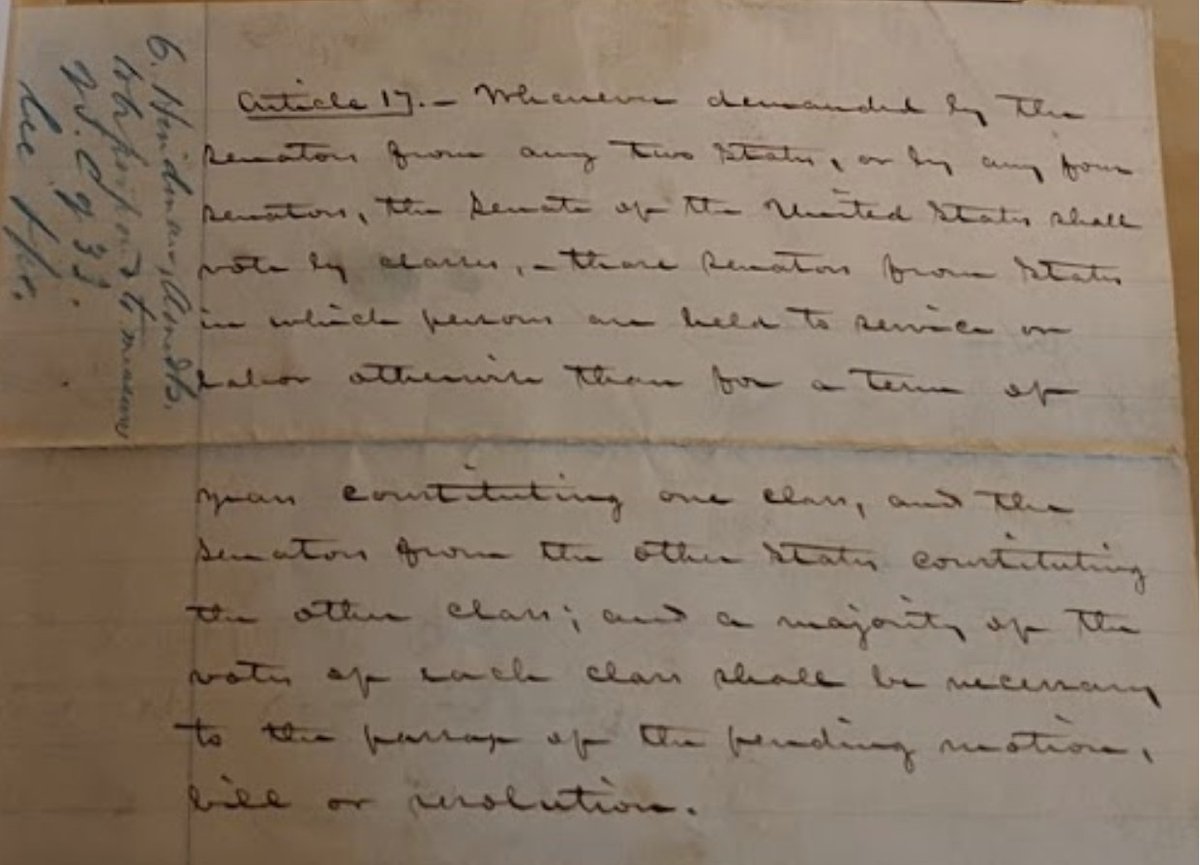

And then there& #39;s the would-be 17th Amendment, in which the Senate would be divided into two classes — the slave-state class and the non-slave-state class — and "a majority of the vote of each class shall be necessary to the passage of the presiding motion, bill or resolutions."

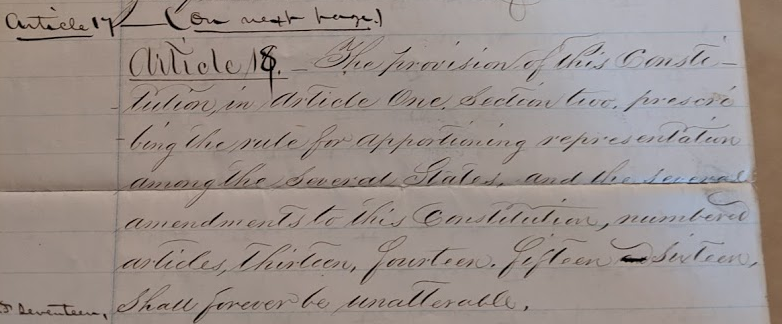

And to ensure the slavery question would be forever settled, one last amendment was needed.

The 18th Amendment: "The provisions of ... the several amendments to this Constitution, numbered Articles 13, 14, 15, 16, and 17, shall forever be unalterable."

There& #39;d be no going back.

The 18th Amendment: "The provisions of ... the several amendments to this Constitution, numbered Articles 13, 14, 15, 16, and 17, shall forever be unalterable."

There& #39;d be no going back.

To the proponents of these amendments, what they sought was no more than the preservation of the Union as it had always been, and had always been intended to be: "We ask nothing but that which is in the Constitution itself. The Constitution [ ] recognizes slaves as property."

The idea that "all men are created equal" had literally meant *all* men was "too absurd to talk about. The men of the Revolution were white men… It was all they meant; it was all they intended; it was all that was understood by any man then living to have been intended by it."

As Sen. Wigfall, TX, noted: "What is the fact as to Massachusetts? Why, on the 18th of July, 1776, they published the Declaration of Independence in the Boston Gazette; and, before God, they published an advertisement for a runaway negro, and offered another for sale. [Laughter]"

In the end, these six proposed amendments would not pass in their entirety, because the Northern states could not accept the parts that expanded slavery to new states – thereby upsetting the balance of power with the South.

But the other parts, the North was willing to accept.

But the other parts, the North was willing to accept.

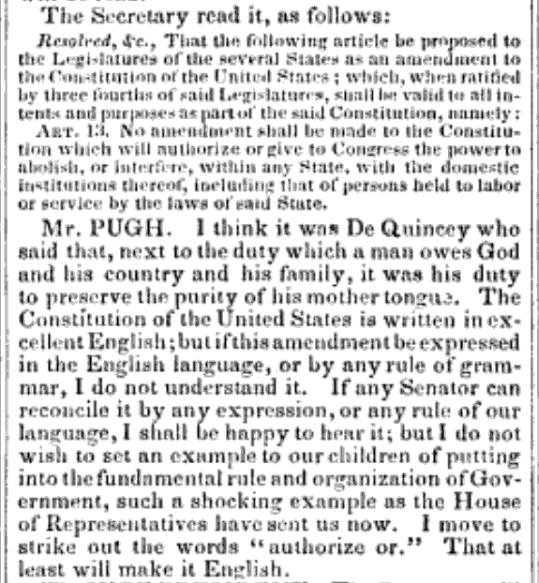

In the end, a compromise 13th Amendment was agreed on: "No amendment shall be made to the Constitution which will [ ] give to Congress the power to abolish or interfere, w/in any State, with the domestic institutions thereof, including that of persons held to labor or service[.]"

Some in Congress did raise objections to the would-be 13th Amendment – for instance, there was an intense debate over the amendment& #39;s awkward phrasing and questionable grammar.

Some thought such terrible grammar would be a bad example to set for children.

Some thought such terrible grammar would be a bad example to set for children.

But as Senator Baker explained in eloquent remarks before the Senate, the 13th Amendment was "not well written, but well meant." A little bad English could be accepted.

Seven months later, Senator Baker – one of President Lincoln& #39;s closest friends – would be killed in battle.

Seven months later, Senator Baker – one of President Lincoln& #39;s closest friends – would be killed in battle.

Because the would-be 13th Amendment wasn& #39;t enough to stop the war. The Northern states were willing to amend the Constitution to offer permanent protection for slavery, if it would keep the Union together. But the 13th wasn& #39;t enough for the South to feel secure; they wanted more.

Besides, it was probably already too late, anyway. It took several weeks for the would-be 13th Amendment to make its way through the House and Senate, and to secure a two-thirds vote from each, and by then, seven of the Southern states had already seceded.

(Plus, many in the South were skeptical of the scheme& #39;s core component: an amendment that says it can never be unamended.

For the South, a permanent guarantee of protection for slavery was a must-have. Not all were convinced this bit of Constitutional judo would really hold up.)

For the South, a permanent guarantee of protection for slavery was a must-have. Not all were convinced this bit of Constitutional judo would really hold up.)

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter

!["Article 13. The right of property in the labor of any person lawfully held to service in the States [ ], ... shall not be abolished or impaired by Congress[ ]; and the United States shall protect all rights of property wherever federal jurisdiction extends." "Article 13. The right of property in the labor of any person lawfully held to service in the States [ ], ... shall not be abolished or impaired by Congress[ ]; and the United States shall protect all rights of property wherever federal jurisdiction extends."](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Ea4bUsAXsAAVDXz.jpg)

![The Amendments That Almost Were did not get better from there.The 14th Amendment: "The power to regulate commerce ... shall not be construed to authorize Congress to make any law impairing the right of the Master to remove from one State to another persons held to service[.]" The Amendments That Almost Were did not get better from there.The 14th Amendment: "The power to regulate commerce ... shall not be construed to authorize Congress to make any law impairing the right of the Master to remove from one State to another persons held to service[.]"](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Ea4e37vWoAAvpCj.jpg)

![The would-be 16th Amendment would have imposed harsh penalties on any state interfering with slavery: "If any state shall enact ... any law impairing [the Fugitive Slave Act] such state shall not be entitled to any representation in Congress [ ] until the the repeal of such law." The would-be 16th Amendment would have imposed harsh penalties on any state interfering with slavery: "If any state shall enact ... any law impairing [the Fugitive Slave Act] such state shall not be entitled to any representation in Congress [ ] until the the repeal of such law."](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Ea4mZMJXkAEMaz8.jpg)

![To the proponents of these amendments, what they sought was no more than the preservation of the Union as it had always been, and had always been intended to be: "We ask nothing but that which is in the Constitution itself. The Constitution [ ] recognizes slaves as property." To the proponents of these amendments, what they sought was no more than the preservation of the Union as it had always been, and had always been intended to be: "We ask nothing but that which is in the Constitution itself. The Constitution [ ] recognizes slaves as property."](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Ea54DKZXQAg-uRZ.png)

![As Sen. Wigfall, TX, noted: "What is the fact as to Massachusetts? Why, on the 18th of July, 1776, they published the Declaration of Independence in the Boston Gazette; and, before God, they published an advertisement for a runaway negro, and offered another for sale. [Laughter]" As Sen. Wigfall, TX, noted: "What is the fact as to Massachusetts? Why, on the 18th of July, 1776, they published the Declaration of Independence in the Boston Gazette; and, before God, they published an advertisement for a runaway negro, and offered another for sale. [Laughter]"](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Ea587SBWAAE29s-.png)