Do you hear that? It& #39;s the Sound of a new Twitter Exhibition...

Most people know that the National Science and Media Museum does photography, film and TV. But not so many people know (yet) that we also do sound!

Grab a cuppa and we’ll tell you all about it https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="☕️" title="Heißgetränk" aria-label="Emoji: Heißgetränk">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="☕️" title="Heißgetränk" aria-label="Emoji: Heißgetränk">

Grab a cuppa and we’ll tell you all about it

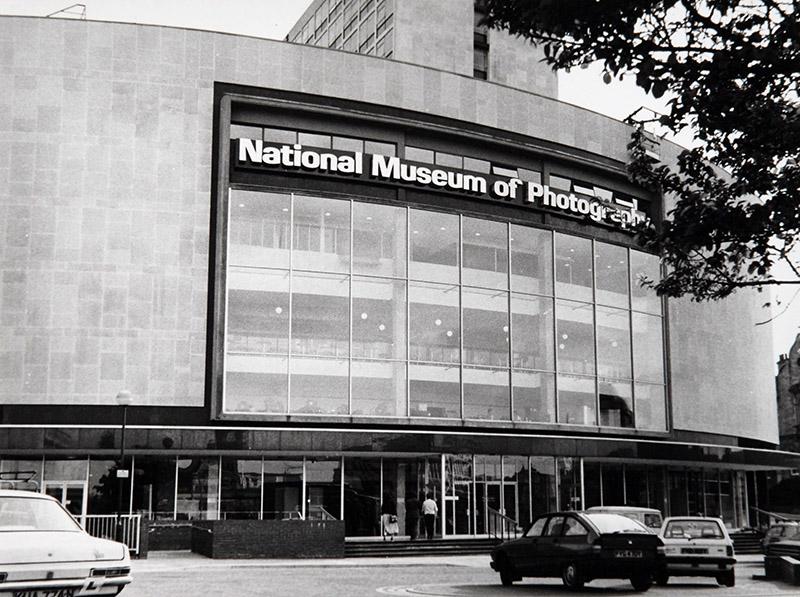

A little history, for starters. We started out on 16 June 1983 as the National Museum of Photography, Film and Television, with the first permanent IMAX installation in Europe (with a pretty cool sound system!)

Then, in 2006, we became the National Media Museum, with a snazzy new glass front on the building! Our main collections were still Photography, Film and Television.

In 2017, the museum had a major refocus and rebranding to become the National Science and Media Museum, with a bigger emphasis on science, AND a new Sound Technologies collection  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🎙️" title="Studiomikrofon" aria-label="Emoji: Studiomikrofon">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🎙️" title="Studiomikrofon" aria-label="Emoji: Studiomikrofon">

But there had always been sound in the collections at the museum – let’s take a look at some examples.

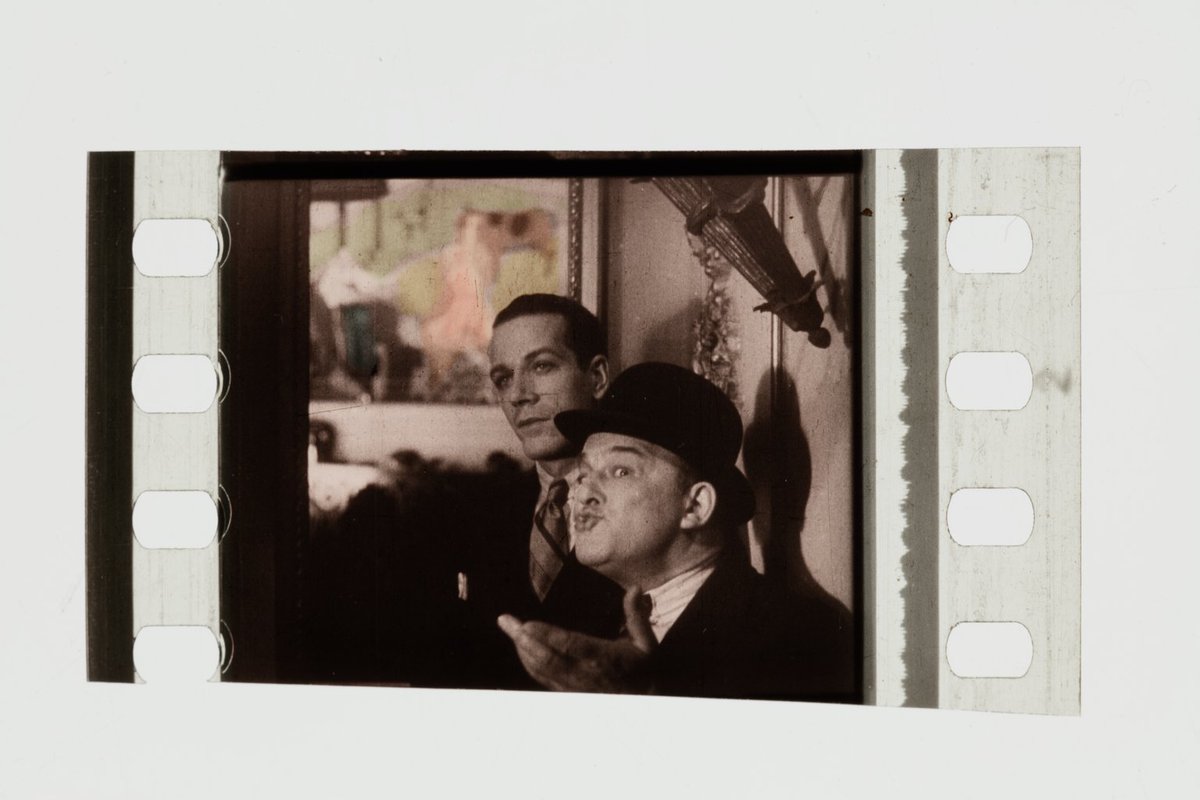

If you’ve seen Singing in the Rain, you’ll know that early ‘talking pictures’ had the sound recorded on gramophone discs. This was a risky business – the disc and the film had to be perfectly synchronised.

This clip from the film shows what happens when disc and film get out-of-synch – as well as many other problems of early talkies https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P6CuBK0cgX4">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

Here’s a Vitaphone disc from the 1930 musical, Sunny. It’s 40.5cm diameter and each side contains around 11 minutes of music – the same length as a reel of film. Sunny had 9 reels and 9 sides to contain the dialogue and the sparkling Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein score.

Here’s a dance scene from Sunny, featuring the star Marilyn Miller, playing at horsey https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dxc8_MWXHcs">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

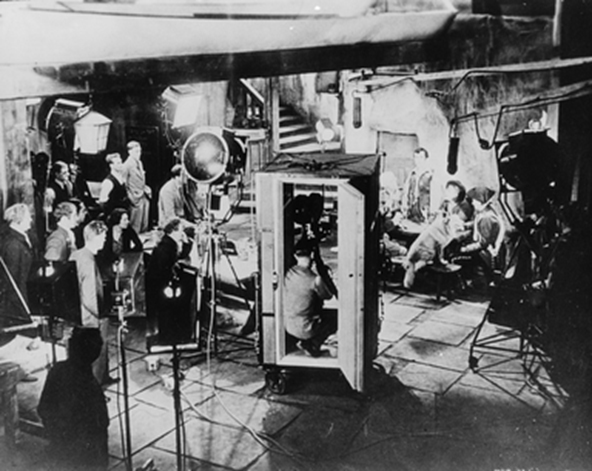

This image from our Kodak Collection shows a “talkie” being made in the studio, with the cine camera encased in a sound-proof booth, so the mics don’t pick up its whirring sound.

Recording the sound on the same film strip, as a pattern of light and dark, alongside the images did away with the problem of synchronisation. This is why we still talk about a film & #39;soundtrack& #39;.

There are also some very cool sound objects in our TV and Broadcast collections. This is the Neve DSP-1. Made in 1981, it was the first fully-digital sound desk. This one was used in an outside broadcast vehicle by BBC radio.

The DSP-1 might be the most complex and expensive sound desk ever made. Only eight were produced. This one was used mostly for Radio 3 opera and orchestral outside broadcasts. The Radio 1 engineers thought it & #39;sounded too clean for rock & roll& #39;

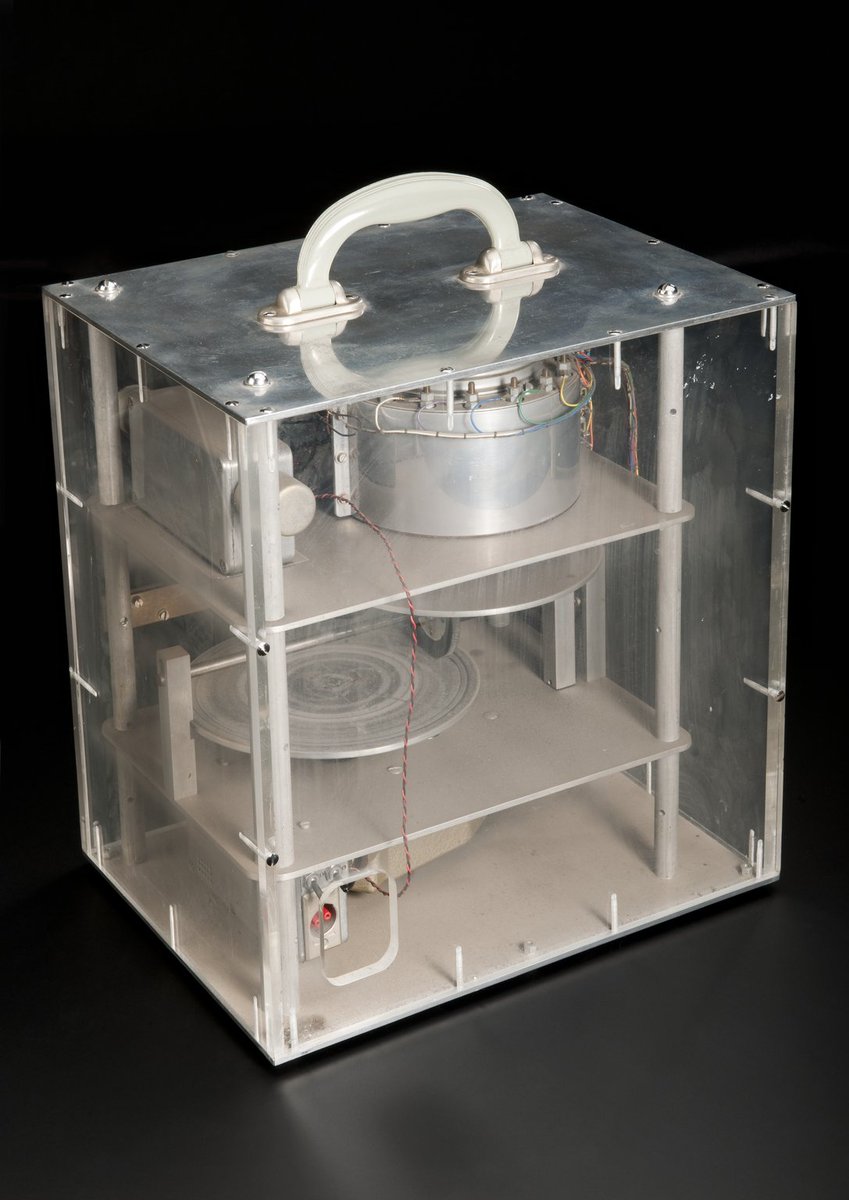

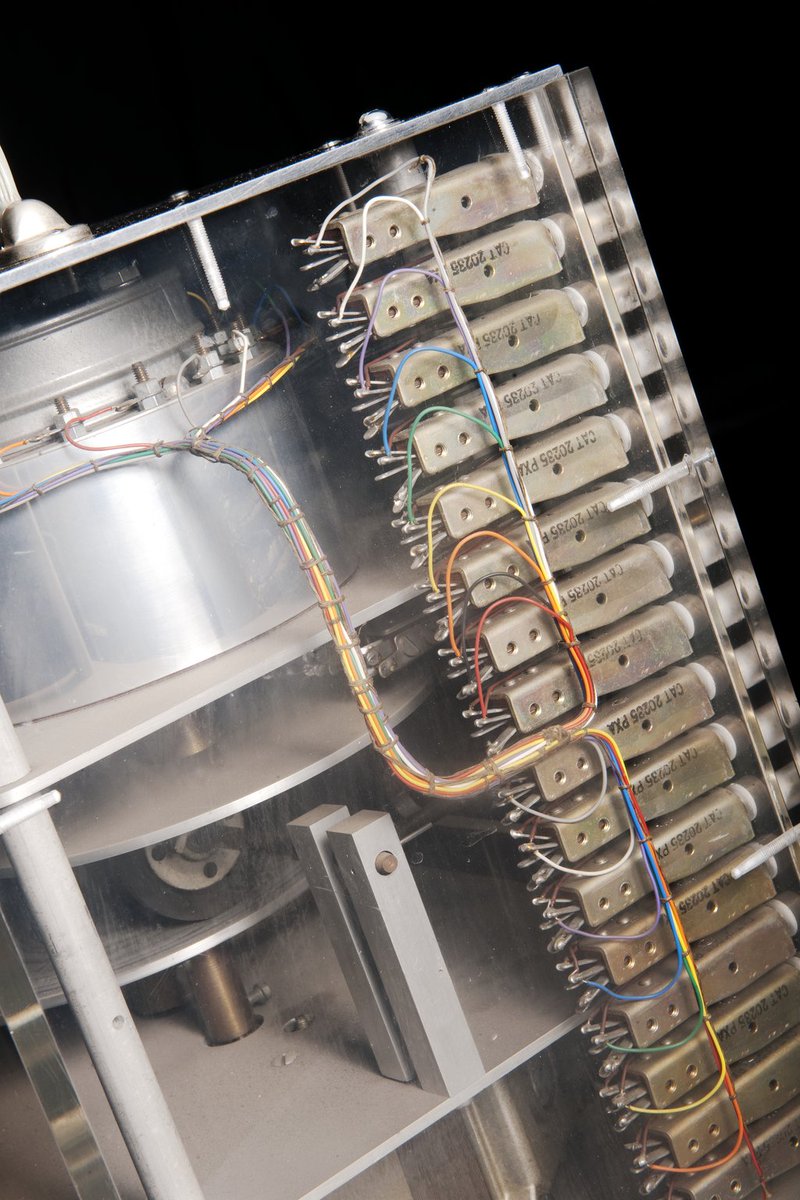

This capacitive fader was designed at the BBC Radiophonic Workshop by engineer Dave Young, in 1967. It was built from parts from a variety of sources, including amplifiers, dictation machines and even fountain pens.

It’s known as the ‘Crystal Palace’, for obvious reasons.

It’s known as the ‘Crystal Palace’, for obvious reasons.

What did it do, you ask? Well, it’s a very early kind of sequencer. The Crystal Palace could control up to 16 sound sources (usually tape players or turntables), allowing the sounds to be mixed in a chosen sequence.

Not to be left out, the Photography collections are a trove of sound-related treasures.

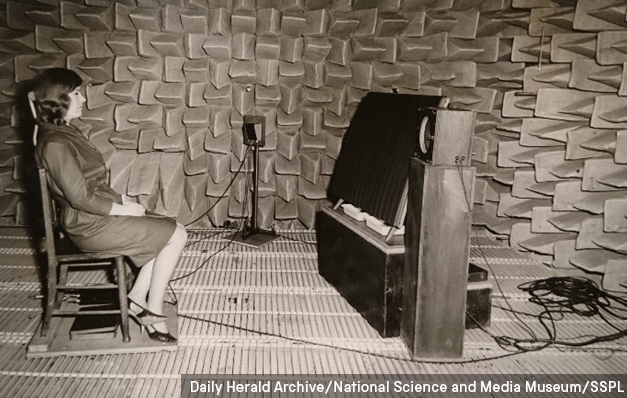

Here, we see research on combating noise in the anechoic room at the National Physical Laboratory, Teddington, in 1964.

Here, we see research on combating noise in the anechoic room at the National Physical Laboratory, Teddington, in 1964.

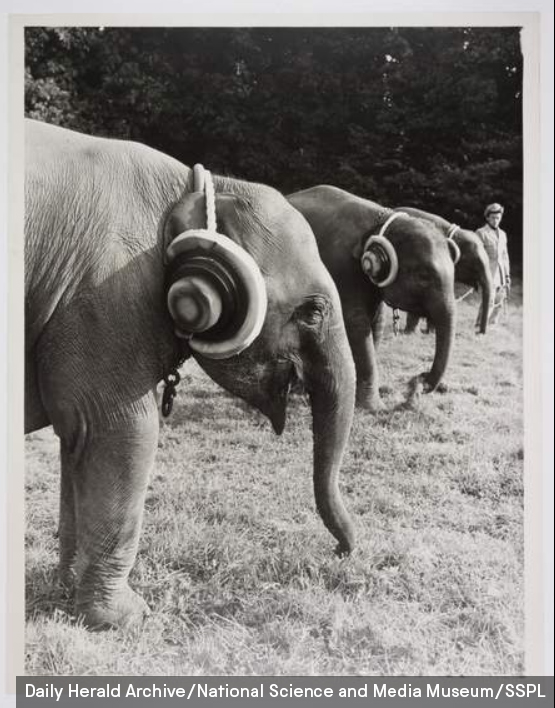

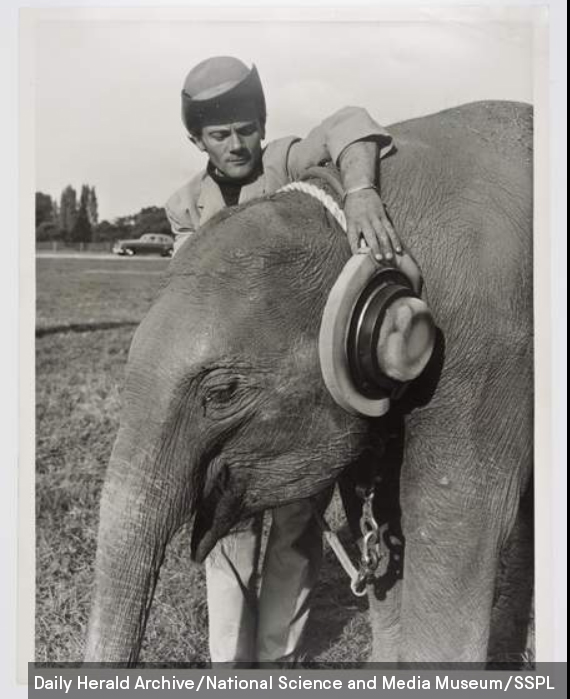

In 1969, young elephants had just arrived at soon-to-open Windsor Safari park. They were so upset by the sound of jet aircraft overhead that they stampeded, trampling down fences! So keepers fitted them with ear muffs to calm them down.

(They did not report whether this worked)

(They did not report whether this worked)

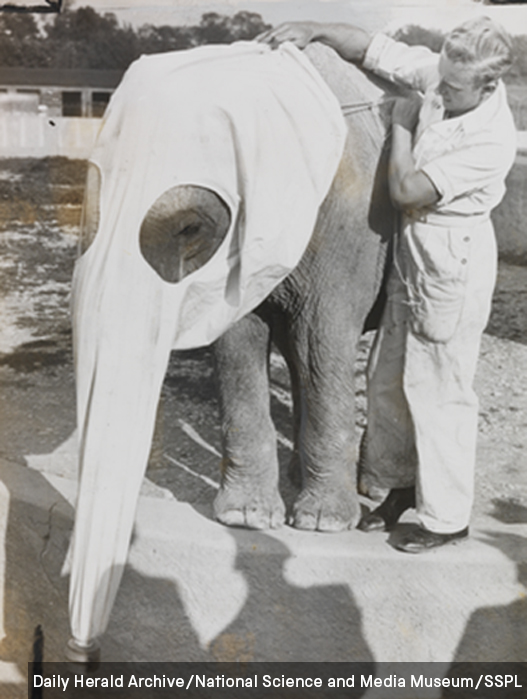

Off topic, but thought you’d like to know: Elephants don’t only need their ears protected. In 1938, zookeepers in Geneva experimented with gas masks to protect their elephants during air raids.

(We don’t know whether this worked either).

(We don’t know whether this worked either).

OK back to sound...

Our museum is part of the Science Museum Group, so we get to share their amazing sound collections too! Let’s look at a couple of their treasures.

Our museum is part of the Science Museum Group, so we get to share their amazing sound collections too! Let’s look at a couple of their treasures.

This auxetophone, from around 1905, uses compressed air (and a big horn) to amplify the sound of an acoustic gramophone. Prior to electrical amplification in the 1920s, this was how you played your records loud enough for a party  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🎉" title="Partyknaller" aria-label="Emoji: Partyknaller">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🎉" title="Partyknaller" aria-label="Emoji: Partyknaller">

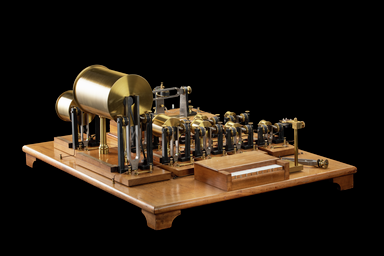

It’s a synthesiser, Jim, but not as we know it  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😊" title="Lächelndes Gesicht mit lächelnden Augen" aria-label="Emoji: Lächelndes Gesicht mit lächelnden Augen">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😊" title="Lächelndes Gesicht mit lächelnden Augen" aria-label="Emoji: Lächelndes Gesicht mit lächelnden Augen">

German acoustician, Herman von Helmholtz, had this built in the 1850s. He wanted to understand why the same note sounds different on different instruments – say a flute and a violin.

German acoustician, Herman von Helmholtz, had this built in the 1850s. He wanted to understand why the same note sounds different on different instruments – say a flute and a violin.

He explored this phenomenon – “timbre” – using this “complete apparatus for the synthesis of sound” which used electro-magnetically-operated tuning forks, amplified by movable brass resonators, and developed his theory of harmonics.

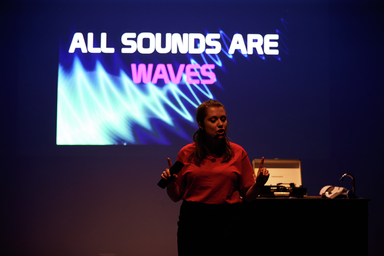

And now we have our very own Sound Technologies collection. It’s got its own Curator and everything.

Do you want a little peek? https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👀" title="Augen" aria-label="Emoji: Augen">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👀" title="Augen" aria-label="Emoji: Augen">

Do you want a little peek?

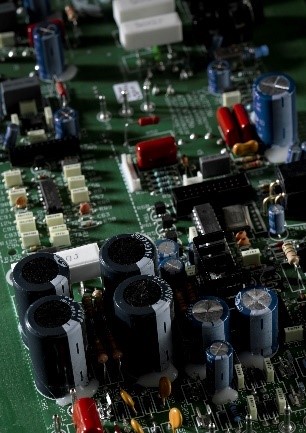

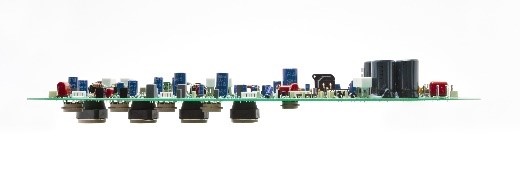

The first object in the collection was this rockin’ Marshall stack, bought brand new in 2017. You might ask why a museum wants a brand new object? Read on…

Lots of the older objects we have in all of our collections – and pretty much all of the radios and TVs in homes until the 1950s - used thermionic valves, like this. But we don’t often see them in modern devices – except guitar amps.

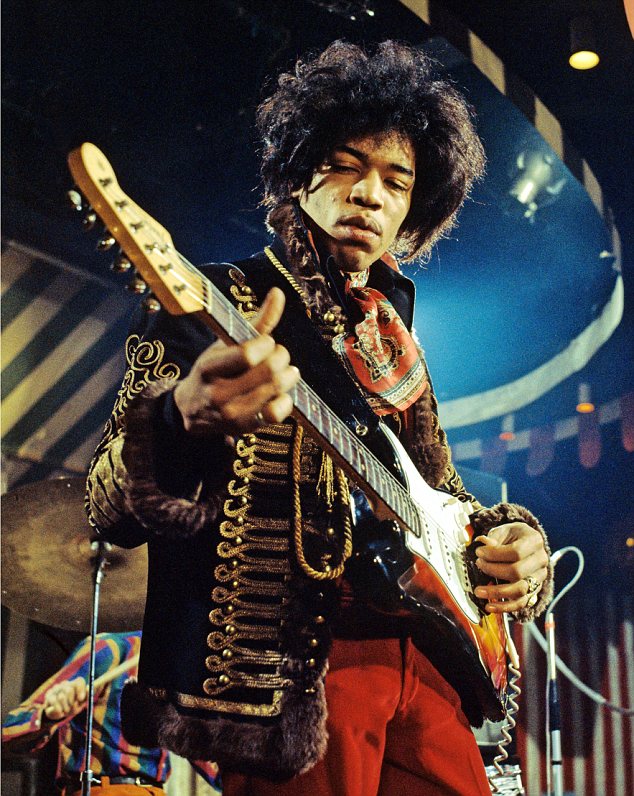

Since the early 1960s, guitarists like Jimi Hendrix here have valued the & #39;warm& #39; but powerful sound of a valve amplifier, so guitar amps are one of the few active markets for valves today, and our Marshall stack demonstrates this.

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="📷" title="Kamera" aria-label="Emoji: Kamera">Photo by Marc Sharratt

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="📷" title="Kamera" aria-label="Emoji: Kamera">Photo by Marc Sharratt

The lovely people @marshallamps were kind enough to provide us with a set of circuit boards from the amp, which inspired our photographer to take these beautiful architectural images.

The smallest thing in the collection is the Nagra Kudelski SN miniature tape recorder.

The company was founded by Polish engineer Stefan Kudelski in the 1950s - ‘Nagra’ means "[it] will record" in Polish.

The company was founded by Polish engineer Stefan Kudelski in the 1950s - ‘Nagra’ means "[it] will record" in Polish.

Small enough to be hidden in clothing, but very high quality, the Nagra SN was used by the CIA, KGB and Stasi for covert recording from the 1960s to 1990s.

It can be seen at work in many films about surveillance and espionage, notably The Conversation (1974).

It can be seen at work in many films about surveillance and espionage, notably The Conversation (1974).

By contrast, the biggest thing in the collection is this Midas XL3 mixing console, from 1990. In its flight case, it’s nearly 2m wide, and weighs more than 300kg.

Used for mixing live performances for artists as diverse as Nina Simone and Bombay Bicycle Club, it has 1254 knobs, 2410 buttons, and 68 faders. And, yes, they do all do something…

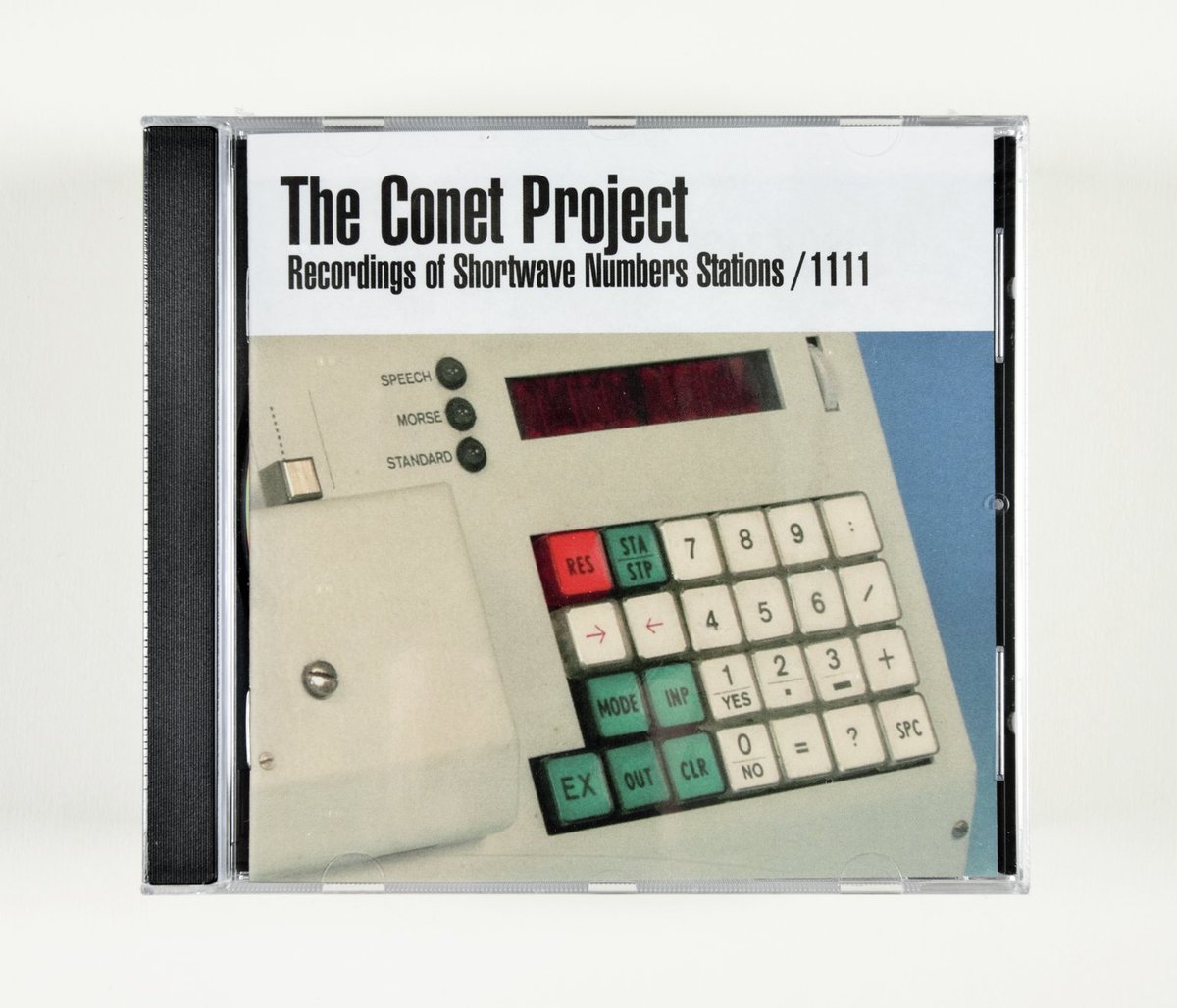

Perhaps the oddest object in the collection is this set of CDs from The Conet Project. These are recordings of ‘numbers stations’ – mysterious short-wave radio broadcasts which contain lists of numbers, occasionally interrupted by short bursts of music.

No one is sure what numbers stations really are, but feel free to enter the internet rabbit-hole if you dare!

We don’t have our own SoundCloud to promote, but you can hear the Conet Project recordings here... https://soundcloud.com/the-conet-project">https://soundcloud.com/the-conet...

We don’t have our own SoundCloud to promote, but you can hear the Conet Project recordings here... https://soundcloud.com/the-conet-project">https://soundcloud.com/the-conet...

And finally, because you can’t have a Twitter thread without a cat, here’s our Copicat tape echo unit.

Watkins Electric Music were early makers of equipment specifically for live, amplified music. The Copicat gave guitarists like Hank Marvin their distinctive, echo-y sound.

Watkins Electric Music were early makers of equipment specifically for live, amplified music. The Copicat gave guitarists like Hank Marvin their distinctive, echo-y sound.

We& #39;ll be talking about sound a lot more, both on Twitter and in our future exhibitions, starting with #SonicFridays this month, where we& #39;ll be asking for your music memories and playlist contributions, plus sharing some of the work of our Sonic Futures project.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter

" title="In 2017, the museum had a major refocus and rebranding to become the National Science and Media Museum, with a bigger emphasis on science, AND a new Sound Technologies collection https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🎙️" title="Studiomikrofon" aria-label="Emoji: Studiomikrofon">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

" title="In 2017, the museum had a major refocus and rebranding to become the National Science and Media Museum, with a bigger emphasis on science, AND a new Sound Technologies collection https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🎙️" title="Studiomikrofon" aria-label="Emoji: Studiomikrofon">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

" title="This auxetophone, from around 1905, uses compressed air (and a big horn) to amplify the sound of an acoustic gramophone. Prior to electrical amplification in the 1920s, this was how you played your records loud enough for a party https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🎉" title="Partyknaller" aria-label="Emoji: Partyknaller">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

" title="This auxetophone, from around 1905, uses compressed air (and a big horn) to amplify the sound of an acoustic gramophone. Prior to electrical amplification in the 1920s, this was how you played your records loud enough for a party https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🎉" title="Partyknaller" aria-label="Emoji: Partyknaller">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

German acoustician, Herman von Helmholtz, had this built in the 1850s. He wanted to understand why the same note sounds different on different instruments – say a flute and a violin." title="It’s a synthesiser, Jim, but not as we know it https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😊" title="Lächelndes Gesicht mit lächelnden Augen" aria-label="Emoji: Lächelndes Gesicht mit lächelnden Augen">German acoustician, Herman von Helmholtz, had this built in the 1850s. He wanted to understand why the same note sounds different on different instruments – say a flute and a violin." class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

German acoustician, Herman von Helmholtz, had this built in the 1850s. He wanted to understand why the same note sounds different on different instruments – say a flute and a violin." title="It’s a synthesiser, Jim, but not as we know it https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😊" title="Lächelndes Gesicht mit lächelnden Augen" aria-label="Emoji: Lächelndes Gesicht mit lächelnden Augen">German acoustician, Herman von Helmholtz, had this built in the 1850s. He wanted to understand why the same note sounds different on different instruments – say a flute and a violin." class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

" title="And now we have our very own Sound Technologies collection. It’s got its own Curator and everything. Do you want a little peek? https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👀" title="Augen" aria-label="Emoji: Augen">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

" title="And now we have our very own Sound Technologies collection. It’s got its own Curator and everything. Do you want a little peek? https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👀" title="Augen" aria-label="Emoji: Augen">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

Photo by Marc Sharratt" title="Since the early 1960s, guitarists like Jimi Hendrix here have valued the & #39;warm& #39; but powerful sound of a valve amplifier, so guitar amps are one of the few active markets for valves today, and our Marshall stack demonstrates this.https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="📷" title="Kamera" aria-label="Emoji: Kamera">Photo by Marc Sharratt" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

Photo by Marc Sharratt" title="Since the early 1960s, guitarists like Jimi Hendrix here have valued the & #39;warm& #39; but powerful sound of a valve amplifier, so guitar amps are one of the few active markets for valves today, and our Marshall stack demonstrates this.https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="📷" title="Kamera" aria-label="Emoji: Kamera">Photo by Marc Sharratt" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

![The smallest thing in the collection is the Nagra Kudelski SN miniature tape recorder. The company was founded by Polish engineer Stefan Kudelski in the 1950s - ‘Nagra’ means "[it] will record" in Polish. The smallest thing in the collection is the Nagra Kudelski SN miniature tape recorder. The company was founded by Polish engineer Stefan Kudelski in the 1950s - ‘Nagra’ means "[it] will record" in Polish.](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EatDYKnXsAEik_6.jpg)