I know the world’s on fire, but a project I worked on for nearly two years (since beginning my postdoc with @chazfirestone) appears this week in PNAS. It combines philosophy & psychology in a way I’m really proud of, and I’d love to share it with you. https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🧵" title="Thread" aria-label="Emoji: Thread">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🧵" title="Thread" aria-label="Emoji: Thread"> https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🚨" title="Polizeiautos mit drehendem Licht" aria-label="Emoji: Polizeiautos mit drehendem Licht"> http://www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.2000715117">https://www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/1...

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🚨" title="Polizeiautos mit drehendem Licht" aria-label="Emoji: Polizeiautos mit drehendem Licht"> http://www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.2000715117">https://www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/1...

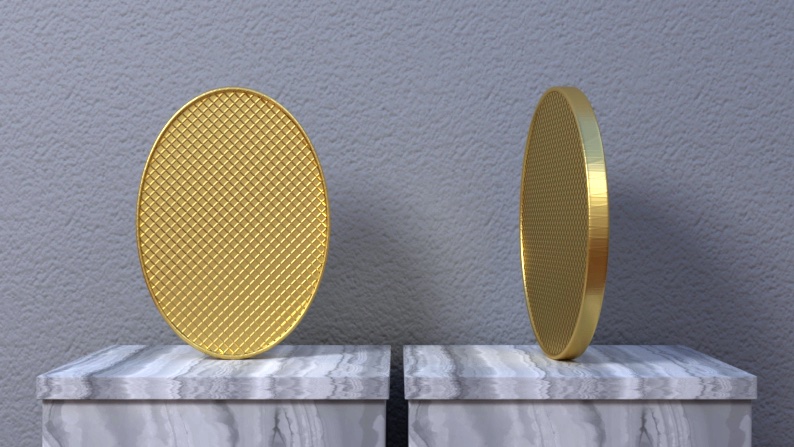

Look at this “coin”. What shape do you see? Your answer bears on a centuries-old philosophical debate on the role of subjectivity in perception. And our answer, based on 9 experiments, appears this week in PNAS!

Paper: https://perception.jhu.edu/perspective

Demos+Data:">https://perception.jhu.edu/perspecti... https://www.perceptionresearch.org/perspective/ ">https://www.perceptionresearch.org/perspecti...

Paper: https://perception.jhu.edu/perspective

Demos+Data:">https://perception.jhu.edu/perspecti... https://www.perceptionresearch.org/perspective/ ">https://www.perceptionresearch.org/perspecti...

Here are some options: The rotated coin (a) looks circular (but if we think about it we can realize it projects an ellipse), (b) looks elliptical (but we can later judge that it’s circular), or (c) looks both elliptical and circular *at the same time*.

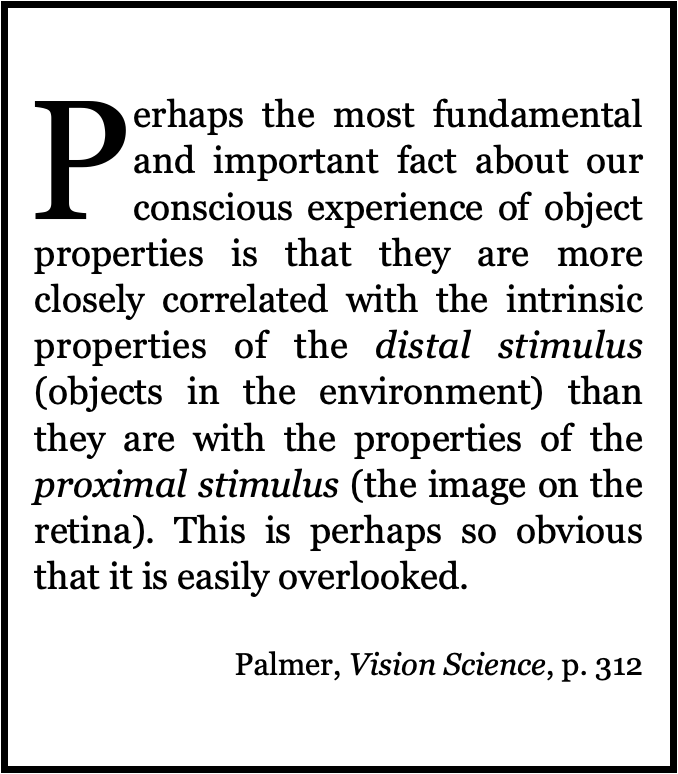

Contemporary vision science—from Marr to popular textbooks—usually goes with (a). We’re taught that perception represents the “distal” properties of objects (i.e. the coin’s circularity), not their “perspectival” properties (i.e. the coin’s elliptical projection).

But wait! Did you know that, long ago, many philosophers held exactly the opposite view? Here’s Locke, for example, basically saying that we see a flat world! (Hume and other British Empiricists had roughly the same view).

And today, philosophers debate this question intensely (including many here on Twitter: e.g. @buffalosentence, @eschwitz, @alvanoe, @eamonbriscoe, @BritHereNow and many more). Some go with (a), some with (b), and some with (c).

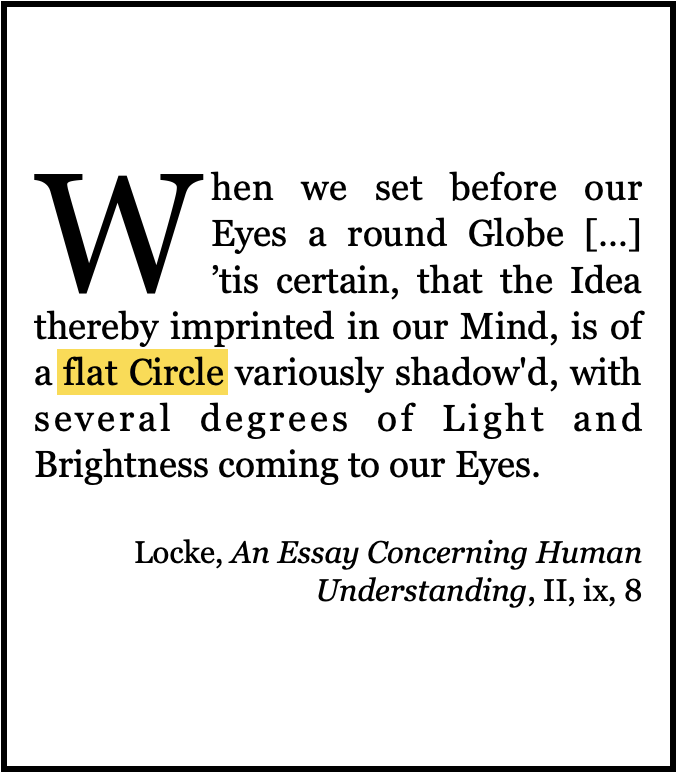

For example, consider these quotes from Schwitzgebel and Smith, who favor (a): The rotated coin looks circular (but if we think hard about it we can realize it projects an ellipse).

Crucially, though, almost all of these philosophical discussions (including those quotes) have been limited to *introspection*. In our new paper, we offer novel *empirical* evidence that directly addresses this centuries-old philosophical question.

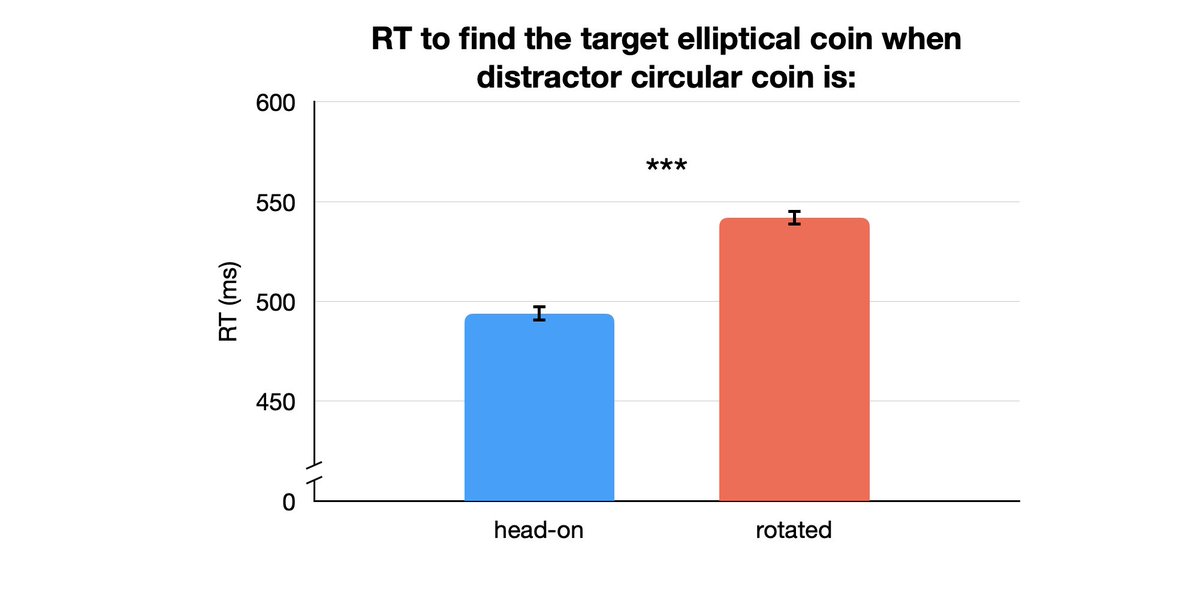

Our logic is simple: If rotated circles look elliptical (in some sense), they should impair visual search for elliptical objects. In other words, when looking for an ellipse, you’d be “distracted” by rotated circles. But that shouldn’t happen if we don’t see perspectival shapes.

So, we created images of rotated and head-on coins, and placed them beside each other. The arrays always had a head-on elliptical coin, and a circular coin (either head-on [left] or rotated [right]). Subjects just had to quickly choose the # with the elliptical coin (here, “1”).

Subjects were slower selecting the elliptical coin when it was next to a circular coin seen head on than when the same circular object was rotated—and hence shared the elliptical target’s perspectival shape. Subjects were very accurate, so this is not a case of misperception.

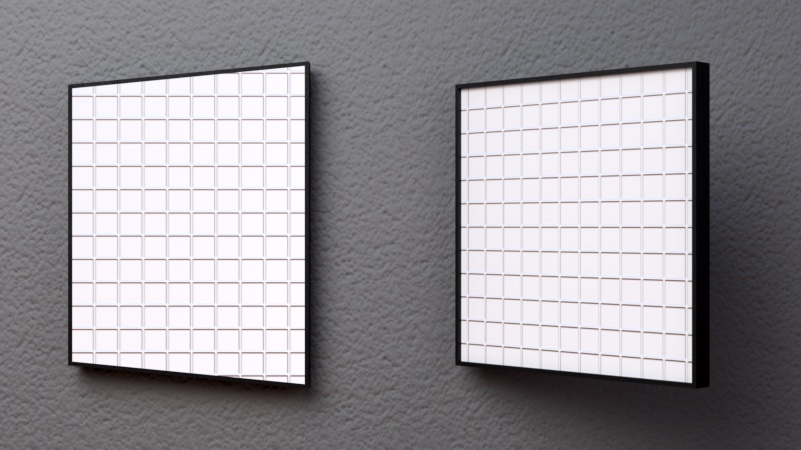

We controlled for all sorts of confounds, and every single time we found the same kind of interference. For example, we controlled for low level properties such as size and rotation, and we showed that the effect generalized to other shapes such as trapezoids & squares.

We also provided rich dynamic cues and allowed longer exposure and delayed responses, but the results were the same. We think that this slowdown effect took place because objects with matched perspectival shapes indeed *look similar*.

Finally, we went big: We laser-cut real objects out of wood and found all of the same effects even in the real world, in maximally naturalistic conditions. This, after all, is the way Locke and Hume wondered about the nature of perception in their studios!

In conclusion, our results suggest that objects have a persistent dual character. They look to us both the way they truly are *and* the way they look “from here.”

A few final thoughts. Hopefully it’s obvious that this is a *very* interdisciplinary project that put in close dialogue philosophy and cognitive science. We used the tools from vision science to put a foundational question in the philosophy of perception to empirical test.

This kind of interdisciplinary work, however, doesn’t happen in a vacuum. True interdisciplinarity needs to be actively fostered. I’m immensely lucky to have found support and training for pursuing this line of work at @chazfirestone’s lab and in the @JohnsHopkins community.

Thanks also to PNAS ( @PNASnews) for seeing the value in this unusual project. We thought to send it there in part because of their vocal support for more collaborations between philosophy and the sciences (e.g., as reflected in this recent piece: https://www.pnas.org/content/116/10/3948)">https://www.pnas.org/content/1...

Many thanks too to undergrad extraordinaire and co-author Axel Bax (he’s too cool for Twitter though). He helped design & build our real-world experiments (which included, among other things, laser-cutters, soldering tens of LEDs & installing 800ft of wire!). Thanks Axel!

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter

![So, we created images of rotated and head-on coins, and placed them beside each other. The arrays always had a head-on elliptical coin, and a circular coin (either head-on [left] or rotated [right]). Subjects just had to quickly choose the # with the elliptical coin (here, “1”). So, we created images of rotated and head-on coins, and placed them beside each other. The arrays always had a head-on elliptical coin, and a circular coin (either head-on [left] or rotated [right]). Subjects just had to quickly choose the # with the elliptical coin (here, “1”).](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EakLkGPXgAEJnks.jpg)

![So, we created images of rotated and head-on coins, and placed them beside each other. The arrays always had a head-on elliptical coin, and a circular coin (either head-on [left] or rotated [right]). Subjects just had to quickly choose the # with the elliptical coin (here, “1”). So, we created images of rotated and head-on coins, and placed them beside each other. The arrays always had a head-on elliptical coin, and a circular coin (either head-on [left] or rotated [right]). Subjects just had to quickly choose the # with the elliptical coin (here, “1”).](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EakLkG5WsAEVAKh.jpg)