UCLA Law Professor Eugene Volokh uses the n-word in his classes, apparently over objections of students who are required to be there and over whom he holds substantial power. His dean apologized, correctly in my view. https://law.ucla.edu/news-and-events/in-the-news/2020/04/note-to-the-ucla-law-community-from-dean-mnookin/">https://law.ucla.edu/news-and-...

Two months ago, Volokh wrote a blog post explaining why he views it as his duty to say the n-word to his students. It is characteristically clear and vigorous. https://reason.com/2020/04/14/ucla-law-dean-apologizes-for-my-having-accurately-quoted-the-word-nigger-in-discussing-a-case/">https://reason.com/2020/04/1...

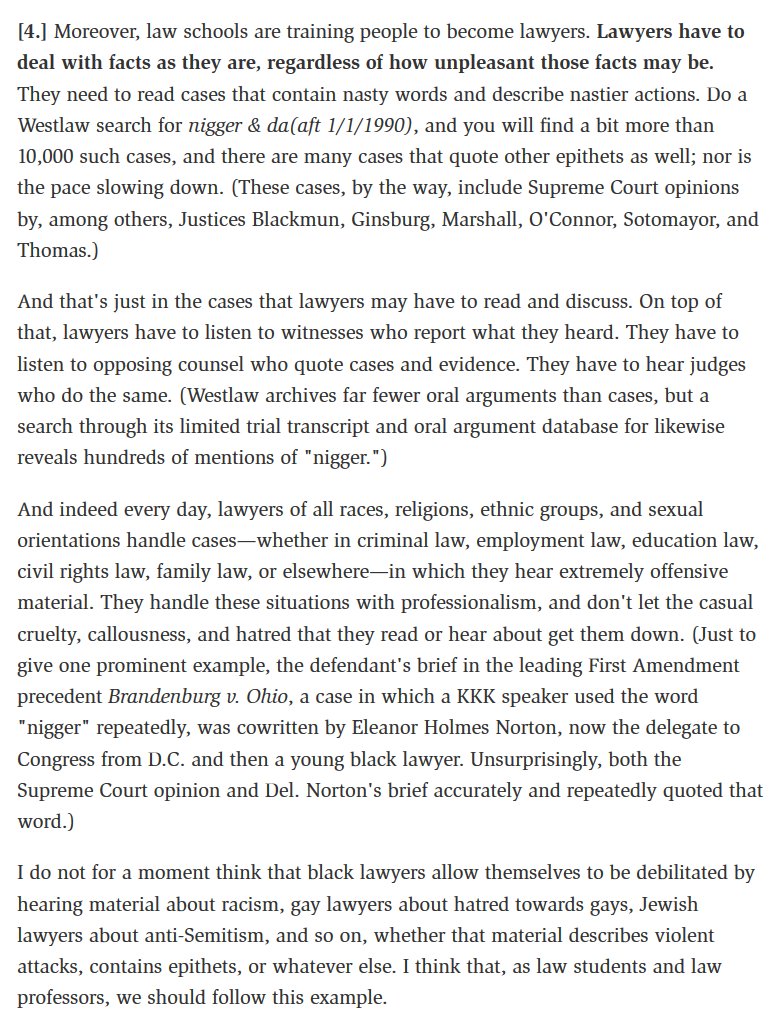

In his post, Volokh offers 5 reasons why he uses the n-word in class. You can decide for yourself whether you find them persuasive.

But his fourth reason focuses on practice. As an experienced practitioner (unlike him), I wanted to explain why I believe it& #39;s wrong.

But his fourth reason focuses on practice. As an experienced practitioner (unlike him), I wanted to explain why I believe it& #39;s wrong.

(I came across this issue because @courtneymilan tweeted about it yesterday in the thread below. I admired her bravery for speaking up to criticize a powerful and widely admired figure, and her example challenged me to speak up too.) https://twitter.com/courtneymilan/status/1270862895174184960">https://twitter.com/courtneym...

"Lawyers have to deal with facts as they are, regardless of how unpleasant those facts may be," Volokh writes. They regularly "hear extremely offensive material" and "don& #39;t let the causal cruelty, callousness, and hatred ... get them down."

Volokh concludes, "as law students and law professors, we should follow this example."

I fail to see how any of that justifies Volokh& #39;s use of the n-word to students in his classes (let alone make it a *duty, as he asserts).

I fail to see how any of that justifies Volokh& #39;s use of the n-word to students in his classes (let alone make it a *duty, as he asserts).

Lawyering does indeed involve some extremely unpleasant things.

For example, I remember vividly, a decade and a half later, the autopsy photos of the injured insides of a child& #39;s genitals (displayed to the jury) that I had to examine for a case.

For example, I remember vividly, a decade and a half later, the autopsy photos of the injured insides of a child& #39;s genitals (displayed to the jury) that I had to examine for a case.

But the fact that I experienced that as a lawyer (and w/o being "debilitated," in Volokh& #39;s words) is not a justification for a professor subjecting his class to gruesome autopsy photos. Only a sociopath would claim otherwise.

I was once chased down a country road by a witness in a pickup truck threatening to kill me. And yet exposing law students to the fear of death is not a law professor& #39;s duty.

I had a biglaw partner get spittle-flying mad at me in a courtroom during a recess. And yet exposing law students to abusive bullying rage is not a law professor& #39;s duty, either.

So Volokh is right that there are unpleasant things lawyers endure in practice. Many are far more unpleasant than mine, of course. But that doesn& #39;t mean law professors get to subject their students to them.

One last point. Volokh& #39;s practice rationale ignores the reality of practice. We may deal with offensive things while working on cases, but, esp. in power-disparity contexts like with judges or subordinates, and esp. in formal settings like court, we take care not to be offensive.

I believe that a vast majority of advocates do not say the n-word in court, or in a CLE presentation, or in a talk to associates in their firm. They don& #39;t want to offend, or they don& #39;t want to be seen as a shitty person, or both.

Ignoring whether the students over whom he holds power are offended by what he& #39;s saying in the somewhat formal context of a law school classroom isn& #39;t imparting some brave real-world lesson: it& #39;s modeling unprofessional, incompetent lawyering.

That& #39;s why I think Volokh& #39;s lawyers-face-bad-things justification for using the n-word in class is a sad pile of horseshit. Thanks for reading.

Quick follow up: Professor Volokh has added 2 more blog posts defending use of the n-word by professors. The 1st links to a new CNN segment featuring Prof Kennedy. Volokh quotes Kennedy& #39;s statement re: why the race of the n-word user is irrelevant. https://reason.com/2020/06/14/prof-randall-kennedy-harvard-law-on-cnn-about-accurately-quoting-racial-epithets/">https://reason.com/2020/06/1...

The 2nd criticizes an undergrad student resolution condemning an art history prof& #39;s use of the n-work whilst discussing NWA. "What have things come to?" he wonders. https://reason.com/2020/06/15/art-history-professor-condemned-by-stanford-undergraduate-senate/">https://reason.com/2020/06/1...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter