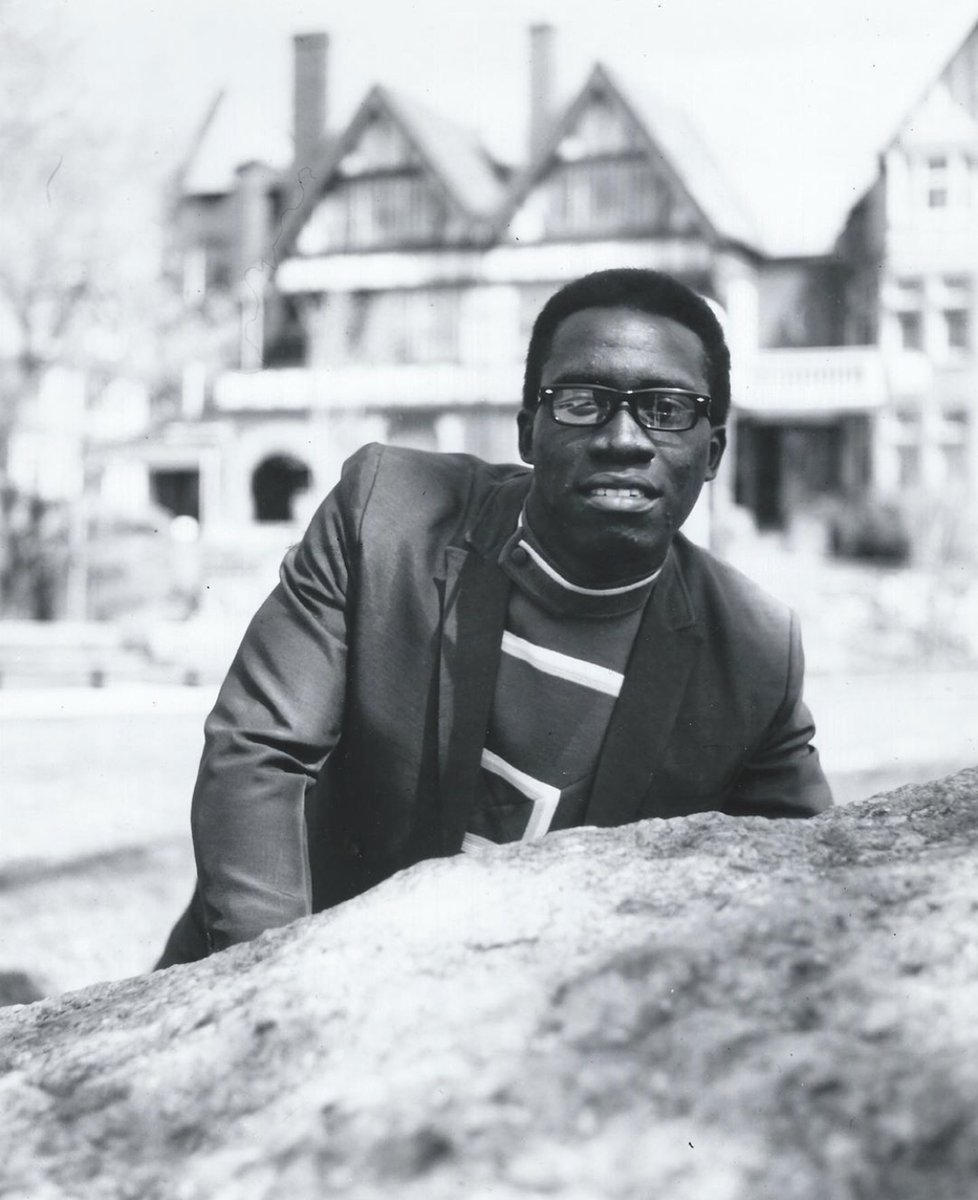

This week, my daughter is among the peaceful protesters seeking justice for George Floyd. Today, I& #39;m telling her about Frank Lynch, a young black soul singer who was murdered by Boston police in 1970, and how Boston& #39;s black community invented a new idea for protesting injustice.

You can ask anyone who was around back then: In early 1970, this song, by 24-year-old Franklin Lynch, had all the hallmarks of becoming a national hit. According to Boston music legend Skippy White, it was climbing the charts in over a dozen cities. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OFzxvRNZyF8">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

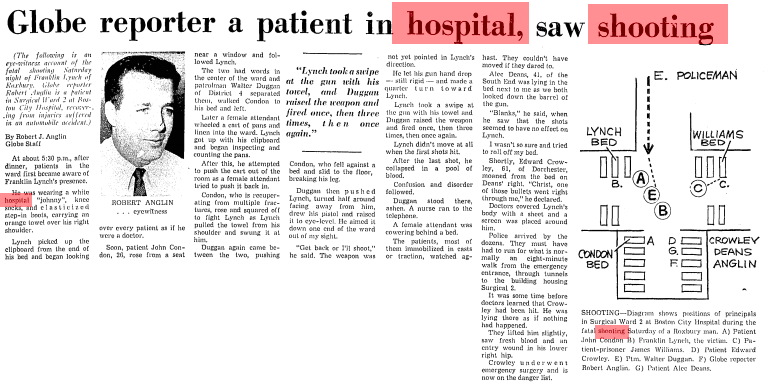

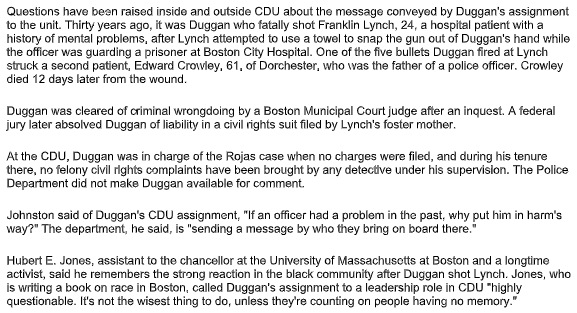

But on March 7, 1970, Lynch was in a crowded ward at Boston City Hospital, wearing a hospital gown, with a cracked shoulder in a sling—an arm, literally, tied behind his back. He allegedly snapped a towel at a police officer named Walter Duggan, who was there to guard a prisoner.

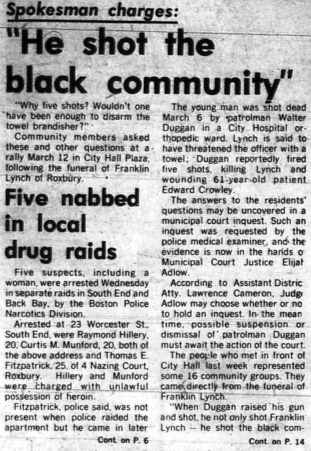

Duggan opened fire, killing Lynch instantly. Another man—the father of a police officer—was gravely wounded and later died. By chance, a Boston Globe reporter was being treated in the ward and published an eyewitness account.

It was an outrageous murder that led to protests in the streets. It worsened relations between Boston& #39;s black community and a progressive mayor. 130 doctors signed an open letter to ban firearms—even in the hands of police—from the hospital in the aftermath of the shooting.

Both of Massachusetts’ Senators—Ted Kennedy and Republican Edward Brooke, the first black man elected to the US Senate—called for the FBI to investigate. And yet, despite numerous eyewitness accounts, a notorious Boston judge failed to charge Duggan with a crime.

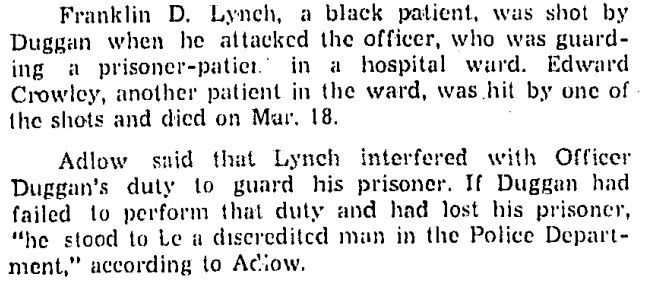

The judge, Elijah Adlow, said Duggan was justified in killing Frank Lynch because the officer was concerned with losing face.

That& #39;s not a typo: A Boston judge ruled that a police officer was justified in killing a black man because that officer could not stand to be embarrassed.

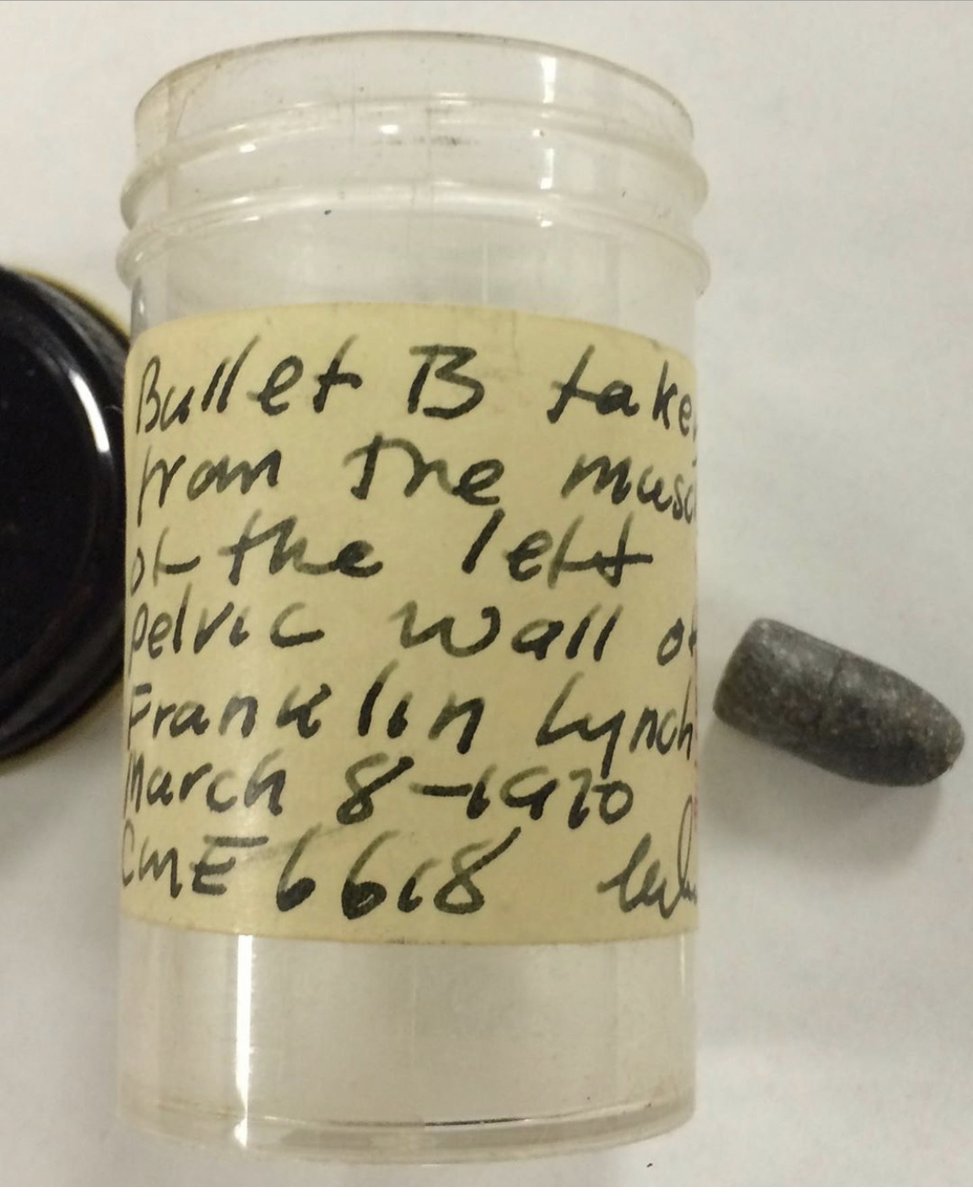

Lynch’s family filed a civil suit in Federal court; a jury found Duggan not responsible for his death. As I was digging through the court records for that case, I came across an old folder and a small jar the size of a pill bottle fell out:

After that I began to call people who were around at the time. I spoke to Hubie Brooks, who had said, not long after Lynch’s funeral: “when Duggan raised his gun and shot, he not only shot Frank Lynch, he shot the black community.”

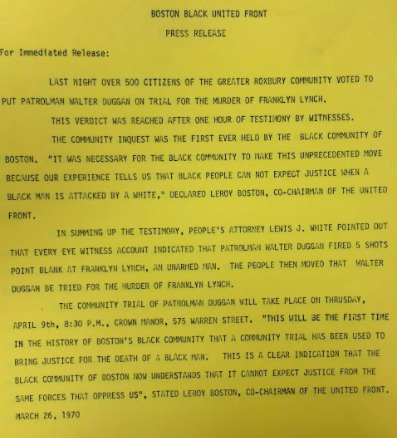

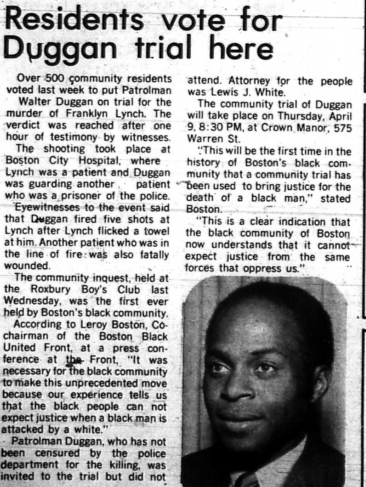

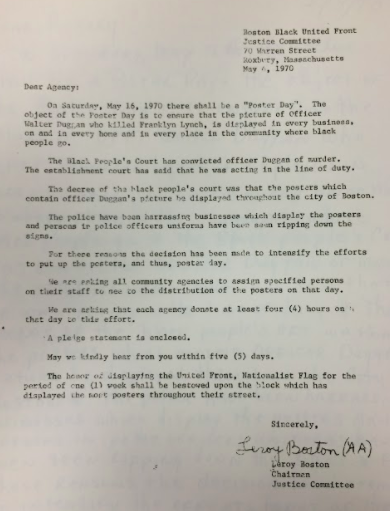

And before his death I spoke to Chuck Turner, who helped found the Boston Black United Front, which was the Black Lives Matter of its day. (The papers of the United Front are preserved at @SeeRCC Roxbury Community College.)

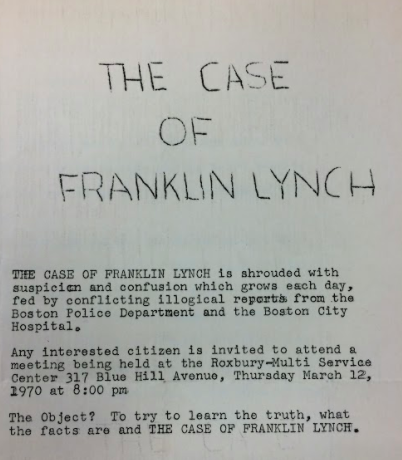

It was the United Front that came up with a new idea: If the city and the country wouldn’t bring charges against this officer and put him on trial, well, maybe the community could.

And it was a controversial idea, even within the black community: there were arguments about it in the @BayStateBanner. But the trial went forward—it was believed to have been the first time Boston’s black community convened its own independent forum for justice.

The mock trial drew a large crowd—about 800 people. Something about this act of civic accountability resonated with me—it echoes down to us now in our own time. Now whenever I hear Cornel West say that justice is what love looks like in public, this is the first thing I think of.

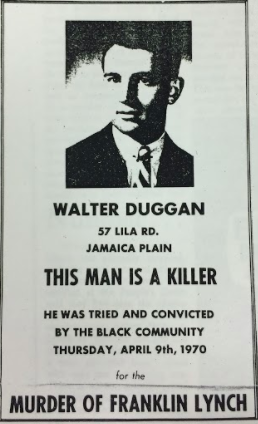

The mock-trial’s sentencing was ahead of its time: today, we might say they doxxed him. They printed up 10,000 posters, with Duggan’s name and face and address on them, saying that he had been tried and convicted of murder by the black community.

People hung them up all over Boston — and kept them up, even when their windows were shot out in the middle of the night.

Walter Duggan retired from the Boston police force in 2003. It appears he spent his later years being put out to pasture—riding a horse in the mounted unit. But not before the Boston Police found one more way to assault Boston’s black community with the memory of Lynch’s murder.

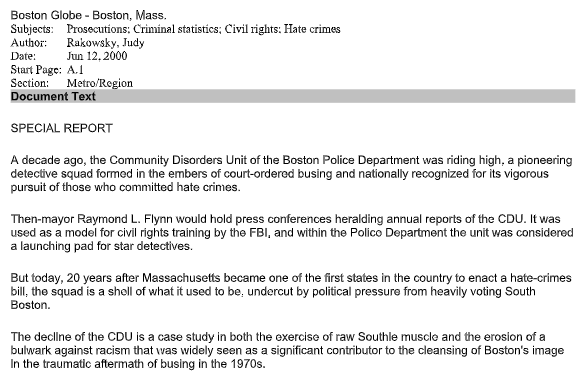

In the 1980s, after court-ordered desegregation of Boston’s schools, the BPD formed a Community Disorders Unit—basically, their civil rights division. For a time, it worked: it focused on hate crimes, a lot of them groups of white men beating up black and Asian men in Southie.

But after a while, Southie got tired of its white sons getting locked up for beating up black kids, and essentially lobbied to have the CDU dismantled. And that’s what happened, more or less: In 2000, the Globe ran a long investigative story on how the CDU had been de-fanged.

In that story, the authors describe the nail in the coffin for the CDU, an act that the Globe called “symbolically telling”: the appointment of Walter Duggan as the assistant commander of the unit charged with enforcing civil rights abuses against the black community.

There is so much more to Frank Lynch’s story—about a young soul singer who’d arrived in Boston from Georgia with a history of mental illness, and was on the brink of national stardom. I wouldn& #39;t know of it if @elipaperboyreed hadn& #39;t covered "Young Girl" and told me about Lynch.

If you are protesting this week, thank you: You are making history. As journalists, we need to spend less time covering protests like sports, and more time placing this moment in the context of decades of community resistance to regimes of systemic white supremacy.

-30-

-30-

For more on the history of the Boston Police Department& #39;s record of killing unarmed black men, I highly recommend @Lawrence& #39;s landmark book "Deadly Force," in which BPD, in 1975, shot an innocent black man—and then planted a gun on him to try to frame him. https://www.amazon.com/Deadly-Force-Story-Become-License/dp/0688019145">https://www.amazon.com/Deadly-Fo...

Thanks to everyone who reached out about this thread — including Frank Lynch& #39;s nephew, Joe Nipper, who put us in touch with members of his family. You can read the 6000-word magazine article, by myself and @elipaperboyreed, in this month& #39;s @BostonMagazine. https://www.bostonmagazine.com/news/frank-lynch-death/">https://www.bostonmagazine.com/news/fran...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter