#TheCompleteBeethoven #313

Symphony No. 3 in E-flat major, Op. 55 "Eroica" (1803-4)

1/ "In his own opinion it is the greatest work that he has yet written ... I believe that heaven and earth will tremble when it is performed." - Ferdinand Ries https://youtu.be/cziRynzmWaA ">https://youtu.be/cziRynzmW...

Symphony No. 3 in E-flat major, Op. 55 "Eroica" (1803-4)

1/ "In his own opinion it is the greatest work that he has yet written ... I believe that heaven and earth will tremble when it is performed." - Ferdinand Ries https://youtu.be/cziRynzmWaA ">https://youtu.be/cziRynzmW...

2/ History has supported Beethoven& #39;s pupil. #ClassicalMusicTwitter voted it Beethoven& #39;s best. It& #39;s more celebrated, analysed and argued over than any other classical music. When @MusicMagazine surveyed 150 conductors, they named it the greatest symphony of all, and I agree.

3/ The Eroica did indeed "shake heaven and earth" (Ries again), yet this most revolutionary work has the humblest of origins. In the winter of 1800-1, Beethoven wrote this unassuming little number for the society dances at Vienna& #39;s Redoutensaal. https://youtu.be/QAS_RZCby2A ">https://youtu.be/QAS_RZCby...

4/ “Only art and science can raise men to the level of God.” - Beethoven

His Promethean fire created three mighty works from this one unpromising lump of clay, beginning with the ballet he was working on at the same time. https://twitter.com/deeplyclassical/status/1244507518505803776?s=20">https://twitter.com/deeplycla...

His Promethean fire created three mighty works from this one unpromising lump of clay, beginning with the ballet he was working on at the same time. https://twitter.com/deeplyclassical/status/1244507518505803776?s=20">https://twitter.com/deeplycla...

5/ In the ballet Prometheus introduces humanity to the ideas of science and art through a succession of dances ending in Dionysus& #39;s Heroic Dance. Humanity celebrates their enlightenment in the finale, which uses the dance for its theme. https://youtu.be/QtLKiBATwUo ">https://youtu.be/QtLKiBATw...

6/ In late 1802 Beethoven returned to Vienna from a summer retreat with his Heiligenstadt Testament, which he kept secret, and sketches for a set of variations on the same theme "written in quite a new style", which he immediately offered for publication. https://twitter.com/deeplyclassical/status/1255385759286206476?s=20">https://twitter.com/deeplycla...

7/ The first surprise is to begin with the bass line on its own, then subject it to three variations before the theme even appears. The symphony& #39;s finale follows the same pattern; the bass becomes the vital force that creates even the theme itself. https://youtu.be/__SHx5bzB7o ">https://youtu.be/__SHx5bzB...

8/ The Op. 35 variations are followed immediately in Beethoven& #39;s sketchbook by a two-page movement plan for an orchestral work in E-flat major, the same key as the variations, the ballet and the dance. There are sketches and material for the first three movements, but no finale.

9/ The third symphony emerged back-to-front. Its conception arose directly from the Op. 35 variations which formed the basis of its finale. As Beethoven put final touches to his 2nd symphony, the Eroica& #39;s first three movements began to metamorphose into their heroic final form.

10/ Beyond the connection to the ballet, the symphony& #39;s initial plan shows no sign of any "heroic" programme. That changed when Beethoven started a new sketchbook to work on his new symphony in earnest. He abandoned his first slow movement idea, and the funeral march was born.

11/ An earlier Beethoven funeral march featured many of the Eroica& #39;s hallmarks, from the & #39;dum-da-dum& #39; dotted rhythm at the start to the central major-key eulogy. This momentous change put a hero& #39;s death and commemoration at the heart of the new symphony. https://twitter.com/deeplyclassical/status/1245239741664169985">https://twitter.com/deeplycla...

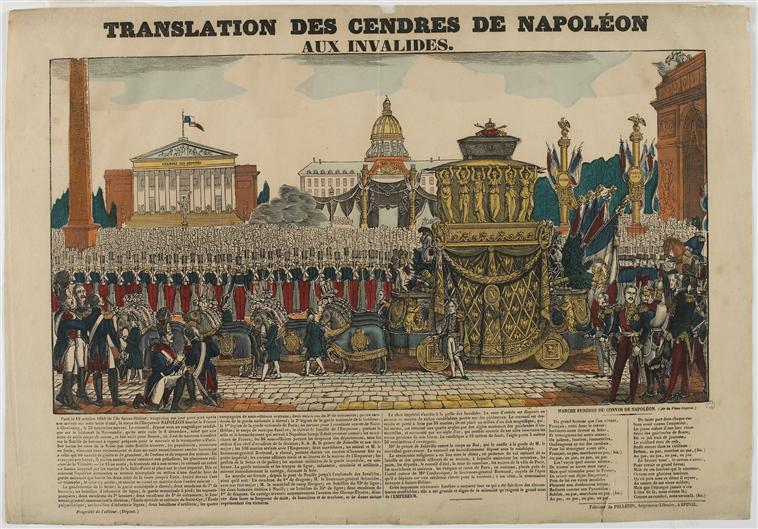

12/ Funeral marches were common in revolutionary France (scene of many military funerals) and in operas of the day. The Theater an der Wien staged a Cherubini opera in March 1803, just days before it hosted the premiere of Beethoven& #39;s 2nd symphony. https://youtu.be/FGH2l2LGeb0 ">https://youtu.be/FGH2l2LGe...

13/ Beethoven knew the audience for his next symphony would recognize the genre he placed at its heart. Austria and France had been at war for a decade. Many might have mourned at funerals for Viennese heroes they knew, maybe their own family or friends. https://youtu.be/6l_bPmJifV4 ">https://youtu.be/6l_bPmJif...

14/ Beethoven& #39;s funeral march made abstract musical form capable of expressing extra-musical ideas, events and characters that his listeners could comprehend: heroism, war, grief, even politics. In the midst of death the Eroica gave birth to a new genre: the programme symphony.

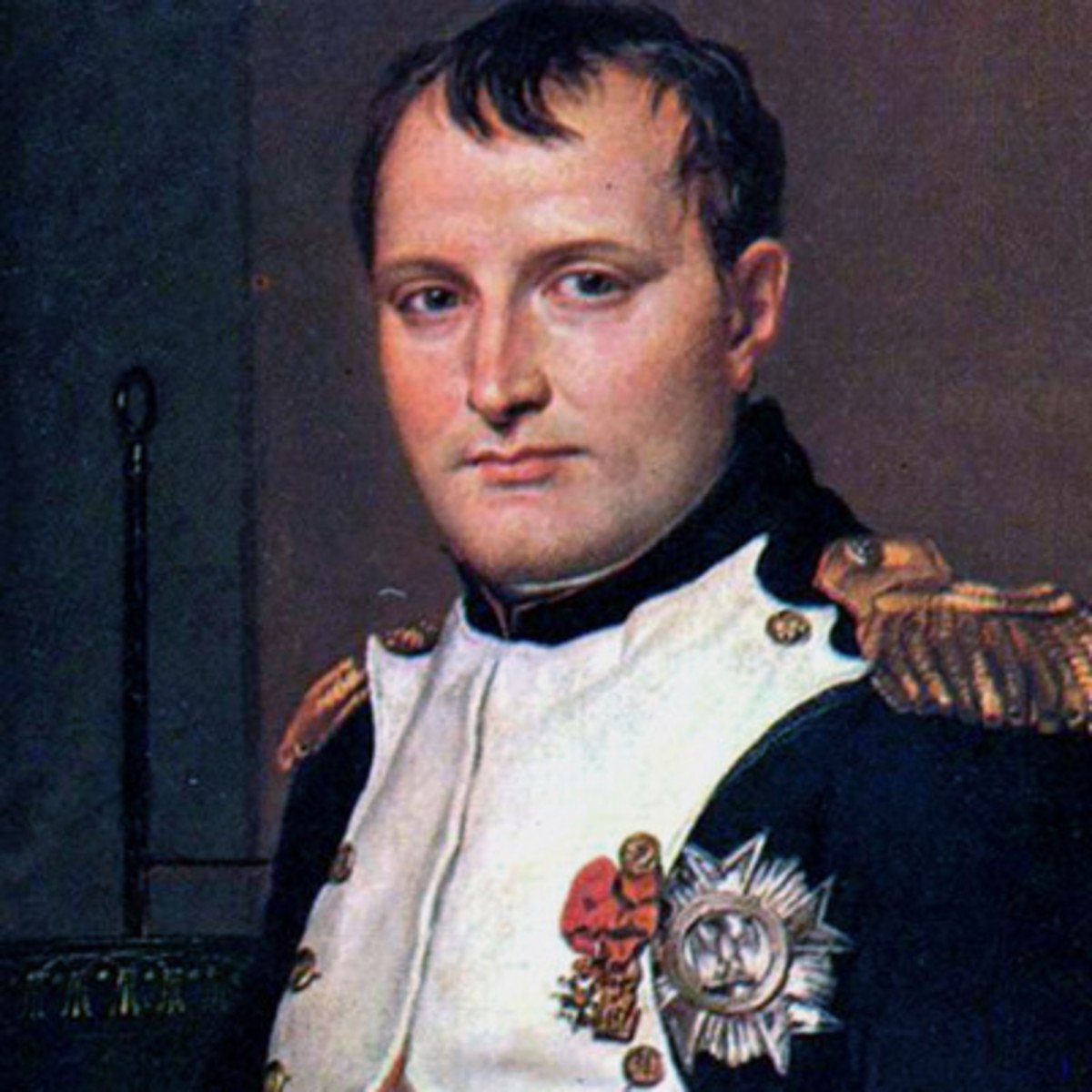

15/ In 1803, as Beethoven& #39;s new inspiration swept through his earlier vision of the remaining movements to transform the symphony into something greater and grander, one man was much on his mind. After a year of fragile peace. Napoleon and his armies were on the march again.

16/ The Napoleon connection is one of music& #39;s greatest legends, but how much of the legend is true? Let& #39;s review the evidence to separate #Eroica fact from fiction. Testimony comes from two star witnesses: Beethoven& #39;s pupil Ferdinand Ries and his secretary Anton Schindler.

17/ The intent was real enough. With work on the symphony well underway, Ries wrote to Beethoven& #39;s publisher: "He wants very much to dedicate it to Bonaparte; if not, since Lobkowitz wants it for half a year and is willing to give 400 Gulden for it, he will title it Bonaparte."

18/ Physical evidence proves beyond doubt that Beethoven did write Bonaparte& #39;s name on the title page, then remove it so forcefully that his pen tore a hole in the page. However, does the testimony of our witnesses about the rest of the story stand up under cross-examination?

19/ @Beethoven_Bust Ries& #39;s story that Napoleon directly inspired the Eroica comes from 1838, long after Beethoven& #39;s death:

"In writing this symphony Beethoven had been thinking of ... Buonaparte while he was First Consul. At that time Beethoven had the highest esteem for him."

"In writing this symphony Beethoven had been thinking of ... Buonaparte while he was First Consul. At that time Beethoven had the highest esteem for him."

20/ Beethoven& #39;s real attitude was more ambivalent. A year before beginning the Eroica, publisher Franz Hoffmeister suggested to Beethoven that he write a piece to honour Napoleon and the Revolution. The response?

"You must leave me out, you won& #39;t get anything from me."

"You must leave me out, you won& #39;t get anything from me."

21/ How then did Beethoven get the notion of a Bonaparte symphony? According to Schindler:

"The Ambassador of the French Republic to the Austrian Court was at that time General Bernadotte, who later became King of Sweden. His salon was frequented by distinguished persons ..."

"The Ambassador of the French Republic to the Austrian Court was at that time General Bernadotte, who later became King of Sweden. His salon was frequented by distinguished persons ..."

22/ "... among whom was Beethoven who had already expressed great admiration for the First Consul ... the suggestion was made by the General that Beethoven should honour the greatest hero of the age in a musical composition."

But there& #39;s a problem with the Bernadotte story too.

But there& #39;s a problem with the Bernadotte story too.

23/ Bernadotte was only the Ambassador to Austria for a few months in 1798, and was nowhere near Vienna in 1803 or 1804. Schindler was no eyewitness: he first met Beethoven in 1814. His account is probably a fabrication either by Schindler himself or his second-hand source.

24/ Ries is also the source for the other half of the tale:

& #39;I was the first to tell him ... Buonaparte had declared himself Emperor, whereupon he broke into a rage and exclaimed, "So he is no more than a common mortal! Now he too will tread under foot all the rights of man."& #39;

& #39;I was the first to tell him ... Buonaparte had declared himself Emperor, whereupon he broke into a rage and exclaimed, "So he is no more than a common mortal! Now he too will tread under foot all the rights of man."& #39;

25/ & #39;"now he will think himself superior to all men, become a tyrant!" Beethoven went to the table, seized the top of the title-page, tore it in half and threw it on the floor. The page was later re-copied and it was only now that the symphony received the title & #39;Eroica.& #39;& #39;

26/ Ries& #39;s 1838 portrayal of the idealistic Beethoven is a story we want to believe, yet the torn title page he describes has in reality survived intact. If part of his account is wrong, can we continue to believe the rest? Is there another, more pragmatic explanation of events?

27/ Where was I? Oh yes.

According to Beethoven scholars William Kinderman and Maynard Solomon, he considered a move to Paris at this time. A Bonaparte Symphony would certainly have helped him make his mark there. When he abandoned his plans, he also abandoned the dedication.

According to Beethoven scholars William Kinderman and Maynard Solomon, he considered a move to Paris at this time. A Bonaparte Symphony would certainly have helped him make his mark there. When he abandoned his plans, he also abandoned the dedication.

28/ As the prospect of war between Napoleon& #39;s France and the Austro-Hungarian empire loomed once more, it might be a bad idea to remain in Vienna and dedicate a symphony to her enemy. Beethoven& #39;s patron, Prince Lobkowitz, was a far more diplomatic (and lucrative) choice.

29/ Beethoven considered dedicating it to Lobkowitz and titling it Bonaparte, but even that idea died once Napoleon had himself crowned Emperor. His hero had fallen leaving only the ideal behind. Lobkowitz got his dedication, but the symphony needed a new title and a new hero.

30/ The first of several trial runs took place at Prince Lobkowitz& #39;s palace in June 1804. Apparently this first performance was terrible, certainly nothing like the @mco_london playing in this excellent if historically inventive dramatization. https://youtu.be/UtA7m3viB70 ">https://youtu.be/UtA7m3viB...

31/ Nevertheless Lobkowitz& #39;s patronage gave Beethoven a unique opportunity to fine-tune in private before going public. For example, he considered dropping the exposition repeat to shorten the immense first movement. Play-throughs with and without convinced him it should stay.

32/ A final trial run took place in January 1805 before a select audience. Then on April 7, still without a title and billed as "a grand symphony in D-sharp" (!), the Eroica was played in public for the first time at the Theatre An Der Wien. https://youtu.be/s5ovX4aThP8 ">https://youtu.be/s5ovX4aTh...

33/ "Extraordinarily pleasing, and really it has so much that is beautiful and powerful, handled with such genius and art."

Sadly for Beethoven, this review wasn& #39;t for the Eroica, but another E-flat symphony performed at the same concert. https://youtu.be/nkjmqkB6x0o ">https://youtu.be/nkjmqkB6x...

Sadly for Beethoven, this review wasn& #39;t for the Eroica, but another E-flat symphony performed at the same concert. https://youtu.be/nkjmqkB6x0o ">https://youtu.be/nkjmqkB6x...

34/ The Eroica, on the other hand, shocked public and critics alike:

"for the most part so shrill and complicated that only those who worship the failings and merits of this composer with equal fire, which at times borders on the ridiculous, could find pleasure in it."

Ouch.

"for the most part so shrill and complicated that only those who worship the failings and merits of this composer with equal fire, which at times borders on the ridiculous, could find pleasure in it."

Ouch.

35/ Reviews of the premiere agreed that "there were very few people who liked the Symphony". Beethoven, who "did not find the applause sufficiently enthusiastic", was to be forever disappointed. The Eroica was played in Vienna only three more times during his lifetime.

36/ While Eberl& #39;s symphony was a hit, the Eroica& #39;s first audiences did indeed "tremble when it is performed", but only in consternation. Why did this music shock them so much?

Time for an analysis. I& #39;ll be using this video as a reference. https://youtu.be/fhHcty9OM-0 ">https://youtu.be/fhHcty9OM...

Time for an analysis. I& #39;ll be using this video as a reference. https://youtu.be/fhHcty9OM-0 ">https://youtu.be/fhHcty9OM...

37/ BTW, unattributed quotes are from early reviews.

"the symphony would gain immensely (it lasts a full hour) if Beethoven would decide to shorten it and introduce into the whole more light, clarity and unity."

Let& #39;s start with the elephant in the room: the symphony& #39;s size.

"the symphony would gain immensely (it lasts a full hour) if Beethoven would decide to shorten it and introduce into the whole more light, clarity and unity."

Let& #39;s start with the elephant in the room: the symphony& #39;s size.

38/ Symphonies had been growing larger, longer and grander. In size, scale and style Eberl& #39;s resembles Haydn& #39;s late symphonies, composed when Beethoven was his pupil a decade before the Eroica. Haydn& #39;s last E-flat symphony breaks the 30-minute mark. https://youtu.be/7ne9Me5F1OI ">https://youtu.be/7ne9Me5F1...

39/ Mozart& #39;s final E-flat symphony is a similar length. The Eroica& #39;s "full hour" made it by far the longest symphony composed up to that time. Its first two movements were each longer on their own then many whole symphonies a generation before. https://youtu.be/44LRfzR5sYY ">https://youtu.be/44LRfzR5s...

40/ But it wasn& #39;t just the length that shocked early audiences. Eberl& #39;s next symphony, also completed in 1804, had an equally long first movement:

"a mighty, bold poem in which the power of this composer and the fire of his mind break free and bold." https://youtu.be/V8WGqQH6wTs ">https://youtu.be/V8WGqQH6w...

"a mighty, bold poem in which the power of this composer and the fire of his mind break free and bold." https://youtu.be/V8WGqQH6wTs ">https://youtu.be/V8WGqQH6w...

41/ #BeethovensContemporaries Eberl gave his audience what they wanted from a symphony post-Haydn:

"unites beautiful and pleasant ideas with novelty, audacity, and power; It is full of vivid ideas, full of brilliant twists and turns, but still united in a beautiful unity."

"unites beautiful and pleasant ideas with novelty, audacity, and power; It is full of vivid ideas, full of brilliant twists and turns, but still united in a beautiful unity."

42/ But every movement of the Eroica started with a shock like nothing audiences had heard before, from the opening hammer-blows (0:21), the funeral march& #39;s subterranean upbeat (16:13), the scherzo& #39;s throb of anticipation (32:02) to the finale& #39;s lightning strike (37:57).

43/ Mozart& #39;s E-flat symphony epitomizes what Beethoven& #39;s audience expected of the genre. Its allegro begins by firmly establishing the home key in two 4-bar phrases (3:43-3:55) that flow with grace, symmetry and poise from tonic to dominant and back. https://youtu.be/WhjOgw-99gU ">https://youtu.be/WhjOgw-99...

44/ The Eroica also begins (0:23) with 4 bars featuring a rising triad, but the home key& #39;s stability is instantly upset when an alien note, C-sharp (0:27), supplants the expected harmony. It takes 8 very unsymmetrical bars (0:27-0:36) to restore order. https://youtu.be/fhHcty9OM-0 ">https://youtu.be/fhHcty9OM...

45/ This is only the first of three statements of the opening theme, each trying to strike out in a new direction. In the second (0:36-0:58) the harmony itself starts to move before the power of the full orchestra (0:59-1:08) breaks the music free from its bonds in the third.

46/ That C# sets in motion a harmonic plan of unprecedented range affecting the entire symphony. C# minor starts the development& #39;s exodus from tonic-related keys (6:17-21). Instead of restoring the tonic, C# sends the recapitulation to the unknown region of F major (10:16-23).

47/ As D-flat, C# soon becomes a key in its own right (10:31-38). Far from re-establishing E-flat, the recapitulation has been forced into two new keys, all by that one little note. Beethoven closes the movement with a coda of unprecedented size. Its first chord? D-flat (13:02).

48/ It& #39;s there to shepherd the mourners away from the hero& #39;s graveside (30:00), and the revellers home at the end of the scherzo (37:29). C-sharp casts a last shadow late in the finale (47:37), before the Presto leaves all darkness behind in an ecstatic rush to the finish line.

49/ The Classical style is "a dramatic style based on tonality" (Charles Rosen). Sonata form dramatizes harmonic movement into a story. Its structure of exposition, development, recapitulation embodies the creation, intensification and resolution of dramatic tension.

50/ The Eroica extends the dramatic range of the Classical style& #39;s tonal language. It also raises the transitions inherent in sonata form to the level of momentous events. The witty, scintillating drama of Haydn and Mozart becomes monumental; it becomes a drama fit for heroes.

51/ For example, the development& #39;s climax (9:31) doesn& #39;t go straight to the recapitulation. Instead, devoid of cadences the harmony becomes uncertain. A hush descends, "fraught with the sense that something *must* happen." (Scott Burnham), its atmosphere something like dread.

52/ The Eroica charges a syntactical join of sonata form with heightened meaning. The recapitulation becomes an impending event, a watershed moment in an inevitable dramatic process "made to seem necessary, not by convention but by the demands of the individual work." (Burnham)

53/ How does Beethoven release the overwhelming tension built up in the development? With a shock of course, launching the recapitulation with music& #39;s most famous mistake (10:07).

"That damned horn player! Can& #39;t he count properly? It sounds infamously wrong!" - Ferdinand Ries

"That damned horn player! Can& #39;t he count properly? It sounds infamously wrong!" - Ferdinand Ries

54/ "How to deepen and extend the range of tone for a symphony of unprecedented size and grandeur? Answer, add one horn.” - Basil Lam

More shocks for the Eroica& #39;s first audience: full three-part harmony in a single instrumental colour, and the scherzo& #39;s shock and awe (34:37).

More shocks for the Eroica& #39;s first audience: full three-part harmony in a single instrumental colour, and the scherzo& #39;s shock and awe (34:37).

55/ The first movement development& #39;s huge tension is only partly resolved in the recapitulation. Beethoven extends classical sonata form& #39;s conventional archiecture with a huge coda (13:02) that finally grounds that energy in page after page of tonic cadences (14:22-15:28).

56/ The finale& #39;s drift toward strange new worlds (47:04) is crushed by another massive coda (48:28) "utterly cancelling any urge or possibility for harmonic adventure" (Burnham). Beethoven closes the book on the drama with hammerblow chords (49:00) that remind us how it began.

57/ Beethoven& #39;s Heroic style shocked its first audiences not by forsaking Haydn and Mozart, but by reforging every element of their style before its listeners’ ears. Its flagship boldly went where no symphony had gone before. Some listeners just weren& #39;t ready for the trip.

58/ The E-flat symphonies of Eberl and Beethoven were both performed in Leipzig. There, the tide began to turn towards the Eroica:

"at the famous Gewandhaus Concerts on January 29, 1807 ... there was an unusual assemblage of amateurs and musicians at the Concert ..."

"at the famous Gewandhaus Concerts on January 29, 1807 ... there was an unusual assemblage of amateurs and musicians at the Concert ..."

59/ "... a deep interest and stillness prevailed during the performance; and the committee were besieged with requests for a repetition, which took place a week later, on the 5th February, and again on the 19th November of the same year."

60/ A review of the 1807 Leipzig concerts hailed the Eroica as "the greatest, most original, most artistic and, at the same time, most interesting of all symphonies."

Two centuries later nothing has changed. Ask the conductors surveyed by @MusicMagazine. They& #39;ll tell you.

FIN

Two centuries later nothing has changed. Ask the conductors surveyed by @MusicMagazine. They& #39;ll tell you.

FIN

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter