It& #39;s been heartbreaking to see so much pain and anguish this weekend, and tragic that a principle as simple as #blacklivesmatter  https://abs.twimg.com/hashflags... draggable="false" alt=""> is still so contested.

https://abs.twimg.com/hashflags... draggable="false" alt=""> is still so contested.

As a historian, I immediately thought of precedents, so I thought I& #39;d share some lessons from my #MormonAmerica research. /1

As a historian, I immediately thought of precedents, so I thought I& #39;d share some lessons from my #MormonAmerica research. /1

Many have shown connections to the 1968 racial riots that similarly enflamed the nation, also in an election year. (Though @TomSugrue has also pointed out key differences.) It just so happens that I& #39;m currently working on Mormonism in 1960s, with eye to racial views. /2

Perhaps what has been so startling is how many different Mormon perspectives there were in 1968, including on the divisive topic of race. There was no clear trajectory or determined position, but a culture in transition. I& #39;ll highlight some examples, & relevance for today. /3

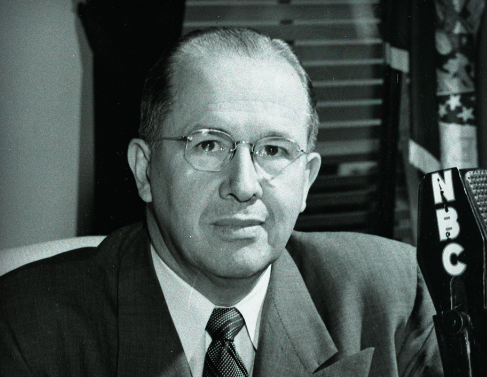

On one side of the spectrum was Ezra Taft Benson, apostle & vocal proponent of far-right views. He consistently associated w/the John Birch movement, and constantly had to be reeled in. He was even tapped by George Wallace as VP for a third-party, racist presidential run. /4

Though he was not allowed to join the campaign, Benson shared Wallace& #39;s views, especially on race. He denounced the Civil Rights movement as puppets of the communists, and declared MLK as a threat to society. He worked hard to hold back any reforms within & without the church. /5

While fewer in American hold such radical views today, there are clear echoes. Because he believed communists were "pulling the strings," he denied agency of black protesters, instead dismissing them as pawns. Same happens when politicians claim paid activists are behind riots./6

Challenging Benson within the church hierarchy were a number of more progressive leaders, including Hugh B Brown, a First Presidency counselor. Brown worked hard to keep Benson in check, and succeeded in convincing church president David McKay to not follow Benson& #39;s lead. /7

Yet while Brown often succeeded at softening Benson& #39;s blow, he was dedicated enough to the institution that he rarely spoke out publicly. And when he did say something that the press jumped on, he quickly backtracked. Expectedly, he prized stability over radical reform. /8

This is a position that often troubles me, because most of his actions, or lack thereof, are fully understandable, but the end result is silence. That stings. It also remains the standard position for LDS leaders today, as the church has stayed silent in the current crisis. /9

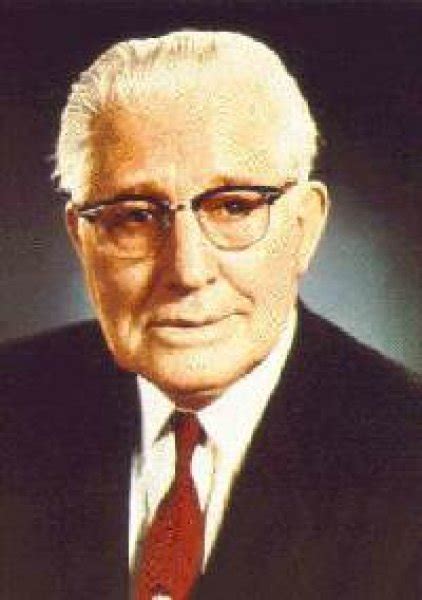

But what about those outside the church? If Benson had accepted Wallace& #39;s invitation, he actually would have only been the second Mormon in the presidential cycle that year. Because George Romney (Mitt& #39;s father) entered the year the frontrunner for the GOP nomination. /10

Romney was governor of Michigan, former president of GM, & had spent a decide of sky-rocketing national acclaim. Part of what made him so likable was he was one of few republicans to champion (a moderate version of) civil rights, and was even backed by Detroit& #39;s NAACP. /11

Romney& #39;s campaign quickly fizzled--he was more successful as a "presumptive" candidate than a real one--and he also displayed the limits of reform. He was careful not to move too far, especially if it would embarrass the church. More word than action--you know the type. /12

Another national LDS voice in 1968: Sterling McMurrin, a University of Utah professor who served as commissioner of education for John F. Kennedy. McMurrin gave several prominent interviews critiquing his church for their racial doctrines and failure to support civil rights. /13

Church leaders met to discuss what to do with McMurrin. None took it as an occasion to reassess their stance. Some, including Benson, called for McMurrin& #39;s excommunication. Brown succeeded in convincing McKay against public action, only because it& #39;d bring more problems. /14

But rather than seeing McMurrin as the true "hero" of 1968 story--the white knight! the successful ally!--what really strikes me is how black residents in Utah, including a small but growing group of black Mormons, pushed the narrative themselves. /15

There were several instances in 1968 where LDS leaders were forced to respond to the actions and agitations of African Americans in Utah and elsewhere. A black convert who worked in Hotel Utah, black students who attended BYU, black believers requesting their own study group. /16

And this doesn& #39;t even include the 4,000 Nigerians requesting missionaries and baptism during the decade. LDS leadership minutes are filled with discussions prompted by black men & women who refused to be silenced, forcing them to make new decisions & consider alternate paths. /17

And you know what& #39;s striking about most of those discussion in Church leadership minutes? They hardly ever mentioned the names of the black men and women they were discussing. They were nameless agitators. /18

What this history screams, at least to me, is not just the different trajectories of white Mormon responses--Benson, Brown, Romney, & McMurrin--but also the need to highlight the marginalized voices as the true drivers of change. To give them a voice and name in our stories. /19

I hope to see plenty of McMurrins speaking out about injustice, the Romneys of the GOP fight for change, & the Browns reeling in the Bensons, but I also hope we provide a platform for those hurt the most by systematic oppression. We need to name them & their work. /fin

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter