As others have noted, this past week has felt like a replay of Chicago 1968 all across the nation.

But it goes much deeper than that.

But it goes much deeper than that.

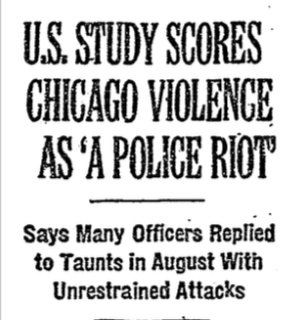

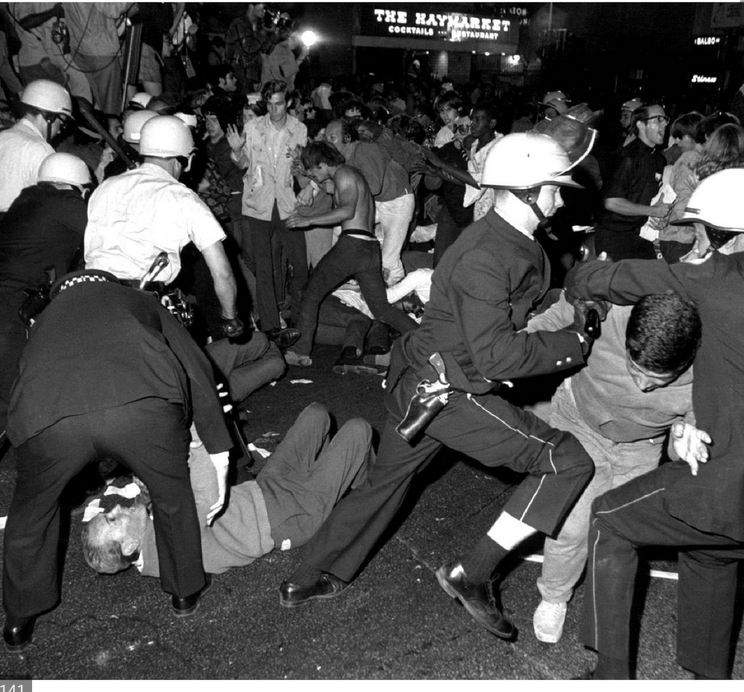

As most people know, the "police riot" in Chicago happened on the Wednesday night of the Democratic National Convention in August 1968, as antiwar protesters outside the convention hall were assaulted by police officers. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3XzdltsTfvE">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

But the story of police brutality is much older than that, of course.

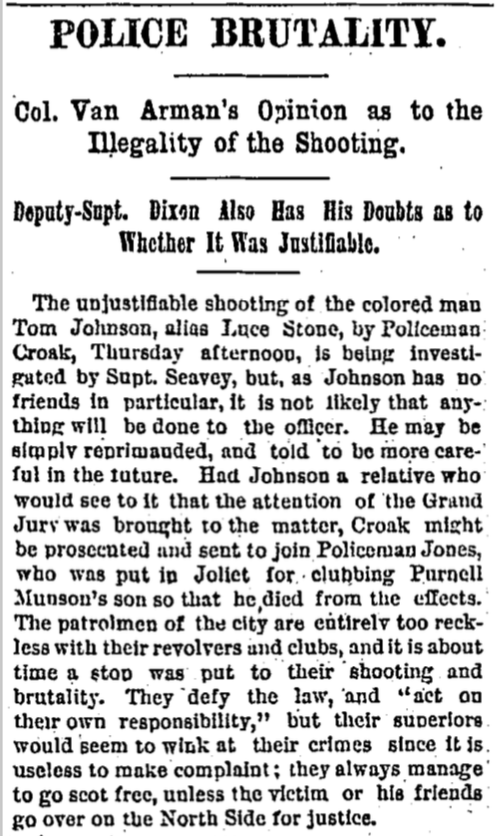

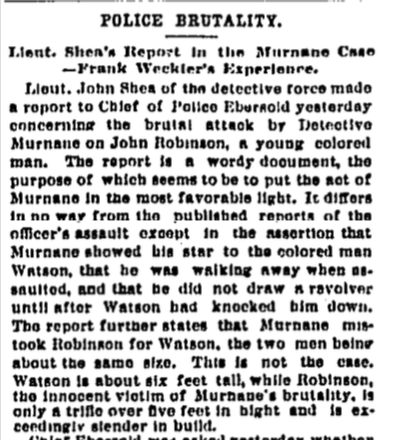

The pages of the Chicago Tribune, for instance, feature stories of police brutality -- often against African Americans -- from a century before. These come from the 1870s and 1880s.

The pages of the Chicago Tribune, for instance, feature stories of police brutality -- often against African Americans -- from a century before. These come from the 1870s and 1880s.

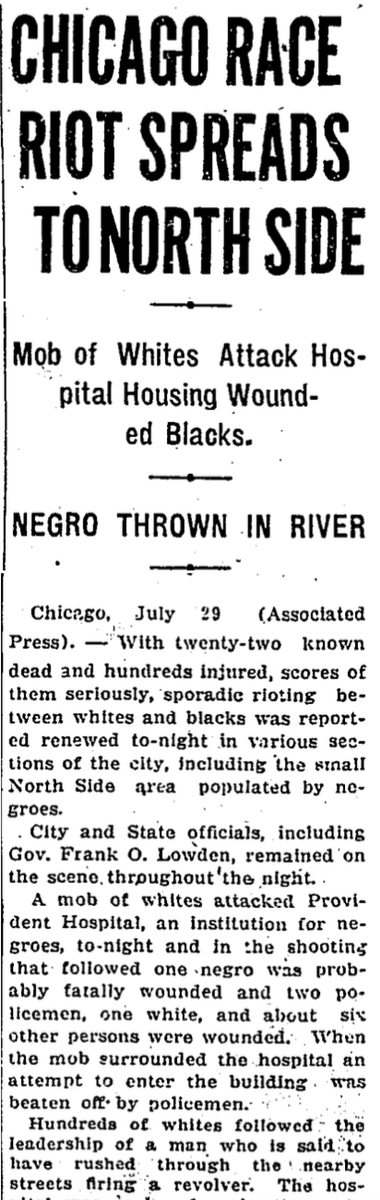

Police brutality came as acts of omission as well as commission.

The 1919 race riot, for instance, started when a black boy floated into the "white" part of Lake Michigan. Whites threw rocks at the boy until he was knocked out and drowned, as a white cop stood by doing nothing.

The 1919 race riot, for instance, started when a black boy floated into the "white" part of Lake Michigan. Whites threw rocks at the boy until he was knocked out and drowned, as a white cop stood by doing nothing.

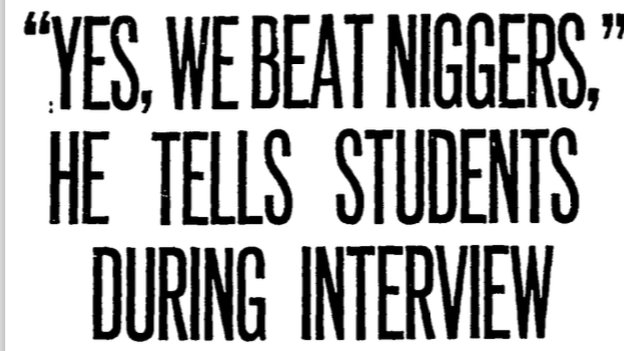

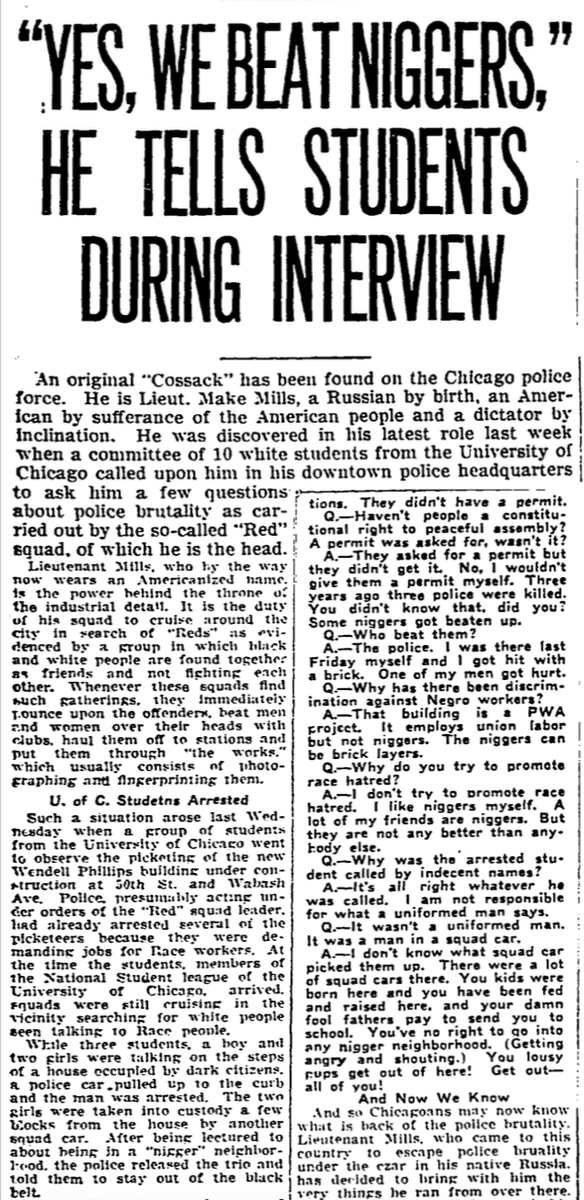

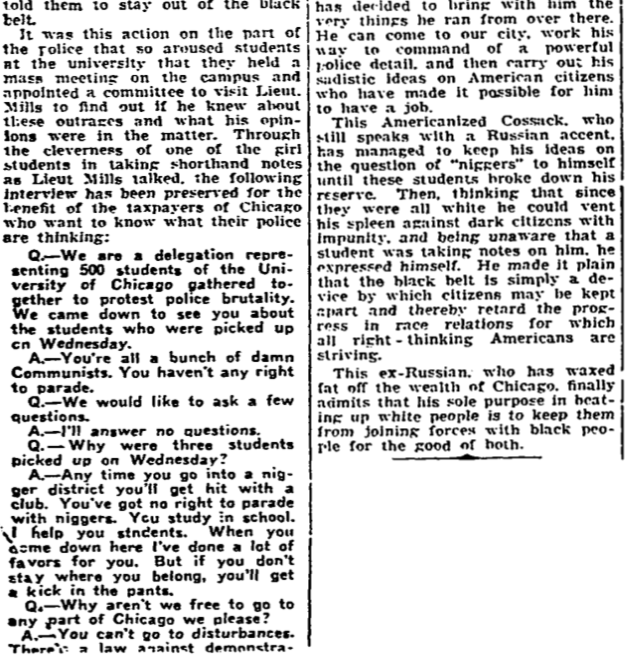

By the 1930s, incidents of police brutality were so commonplace that the black-owned Chicago Defender could run an exposé like this (5/26/34).

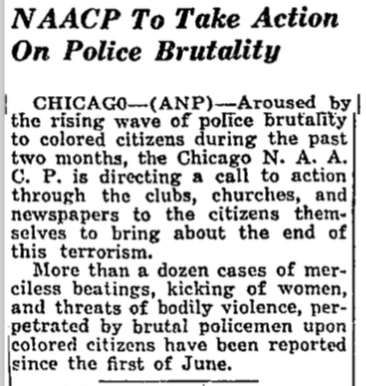

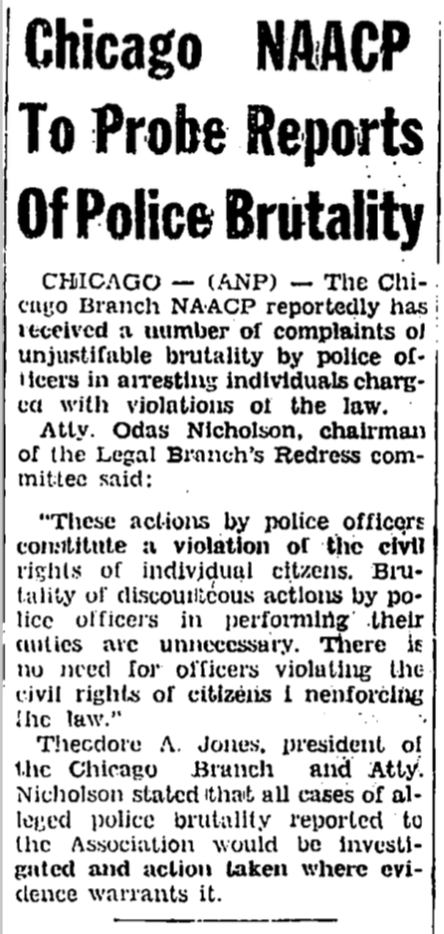

Meanwhile, civil rights organizations like the NAACP launched their own protests and investigations into the wave of police brutality against African Americans in the city.

Here& #39;s a story from 1934:

Here& #39;s a story from 1934:

Investigations, of course, didn& #39;t end the practice.

Indeed, looking over the historical record, it& #39;s striking how little things changed over the years.

Here& #39;s another NAACP inquiry nearly a quarter century later in 1958:

Indeed, looking over the historical record, it& #39;s striking how little things changed over the years.

Here& #39;s another NAACP inquiry nearly a quarter century later in 1958:

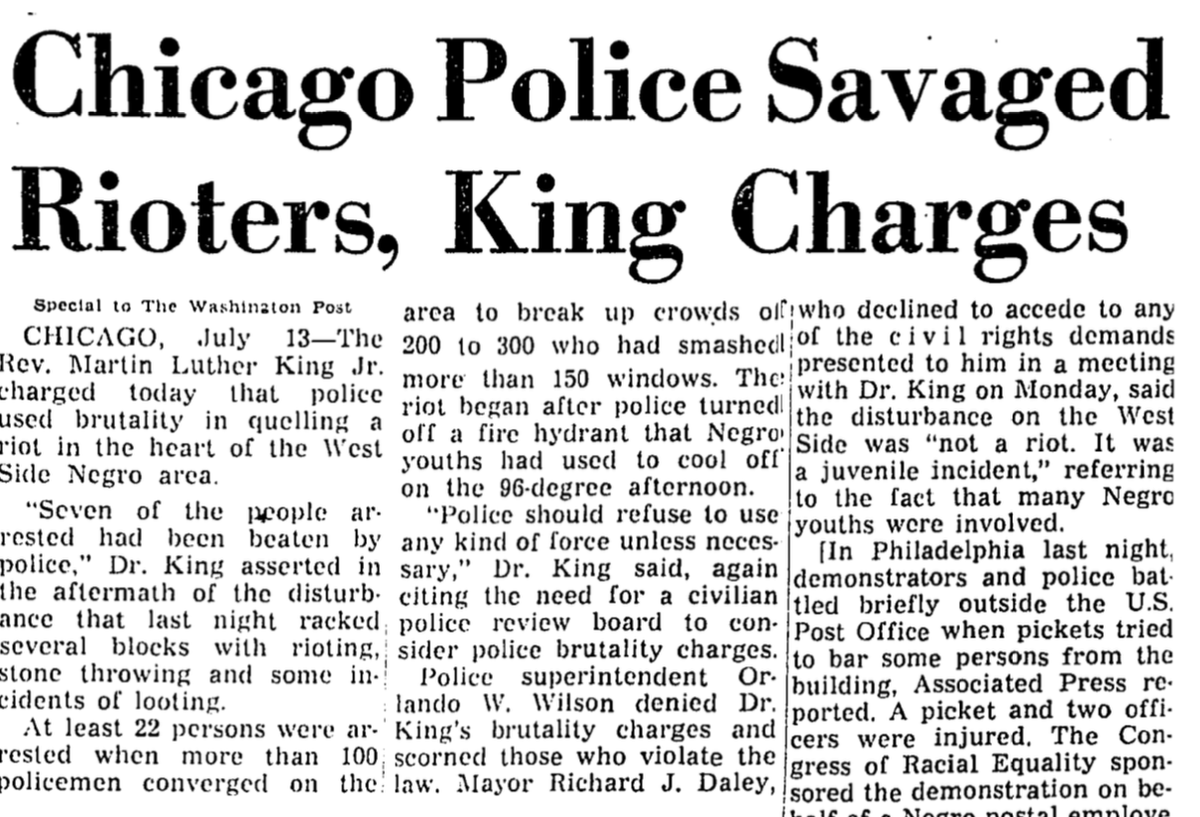

Less than a decade later, in the summer of 1966, MLK staged protests in Chicago to draw attention to the slum conditions of the urban North.

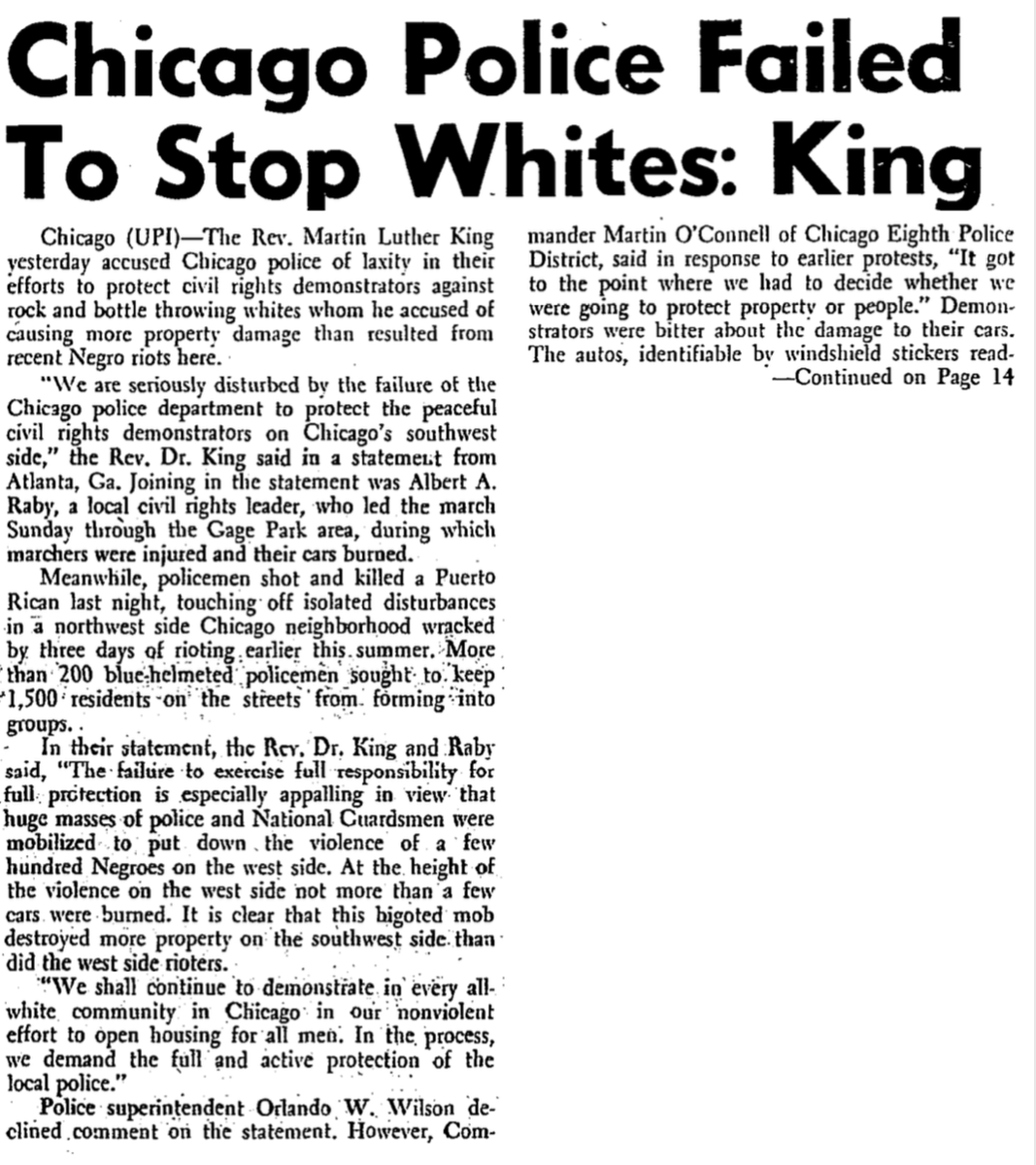

He was struck by how harshly the police handled black rioters and how hands-off they were with white ones just a few weeks later.

He was struck by how harshly the police handled black rioters and how hands-off they were with white ones just a few weeks later.

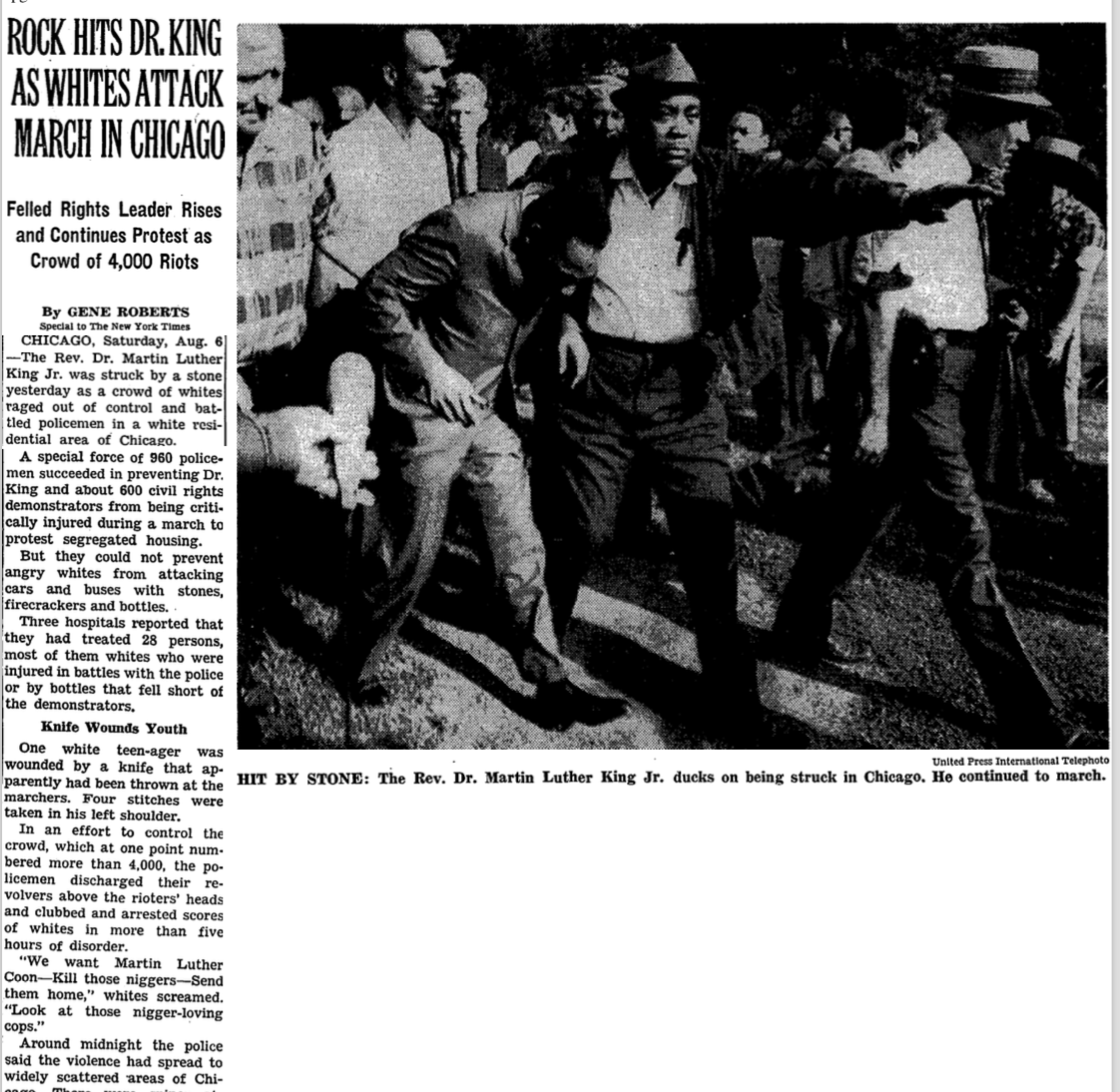

A few days later, King was famously struck by a rock when white mobs staged a counterprotest and turned violent.

Note the last quote here.

Note the last quote here.

When MLK was assassinated a year and a half later in April 1968, cities erupted in some of the worst violence of the decade.

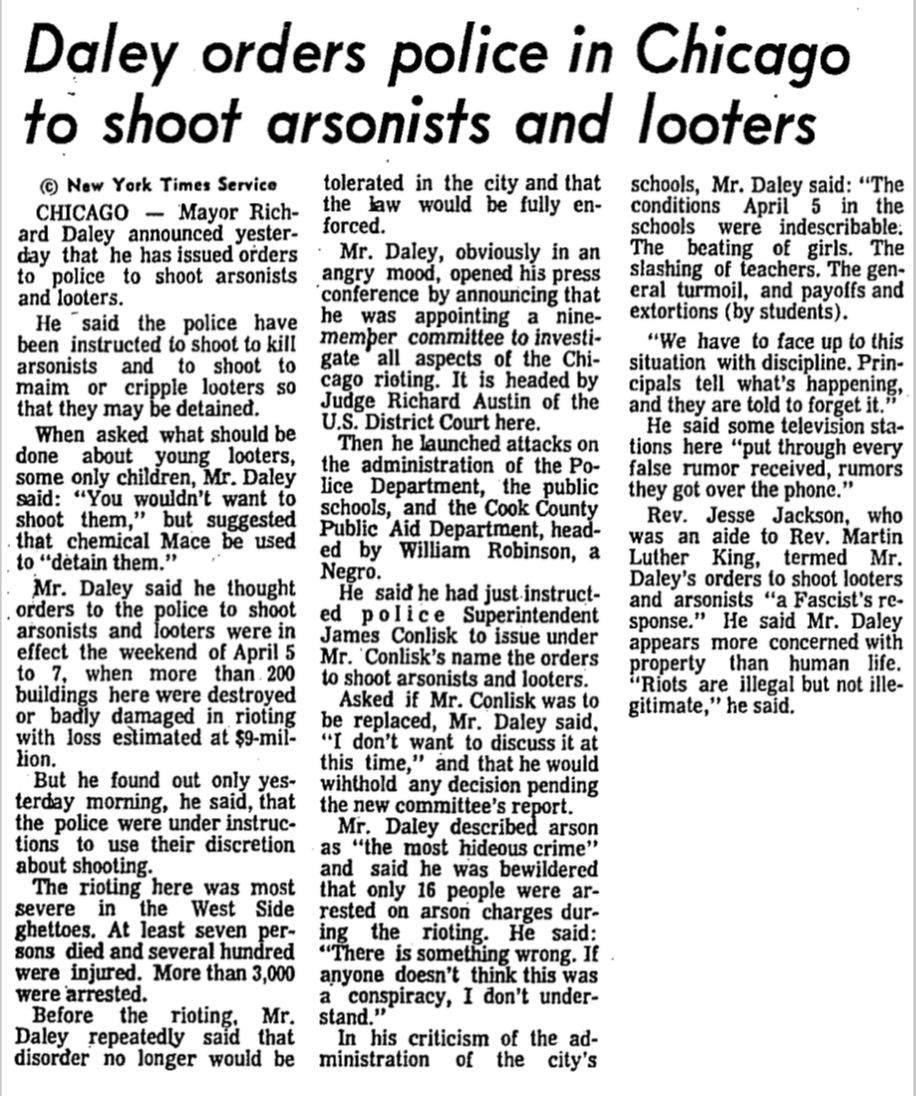

As the West Side went up in flames, Mayor Richard J. Daley ordered cops to "shoot to kill" all arsonists and "shoot to maim or cripple" all looters.

As the West Side went up in flames, Mayor Richard J. Daley ordered cops to "shoot to kill" all arsonists and "shoot to maim or cripple" all looters.

That attitude of overreaction guided his plans for the Democratic National Convention just eight months later.

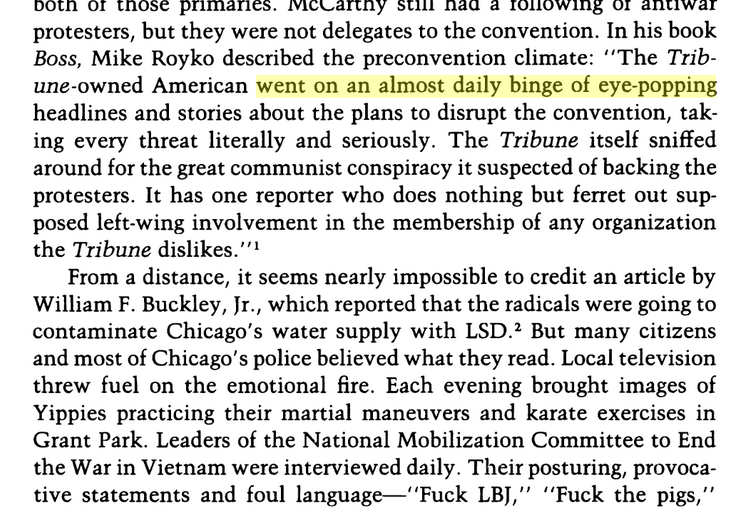

The summer was filled with wild rumors, and local authorities believed them all.

(from Mayor Jane Byrne& #39;s My Chicago:)

The summer was filled with wild rumors, and local authorities believed them all.

(from Mayor Jane Byrne& #39;s My Chicago:)

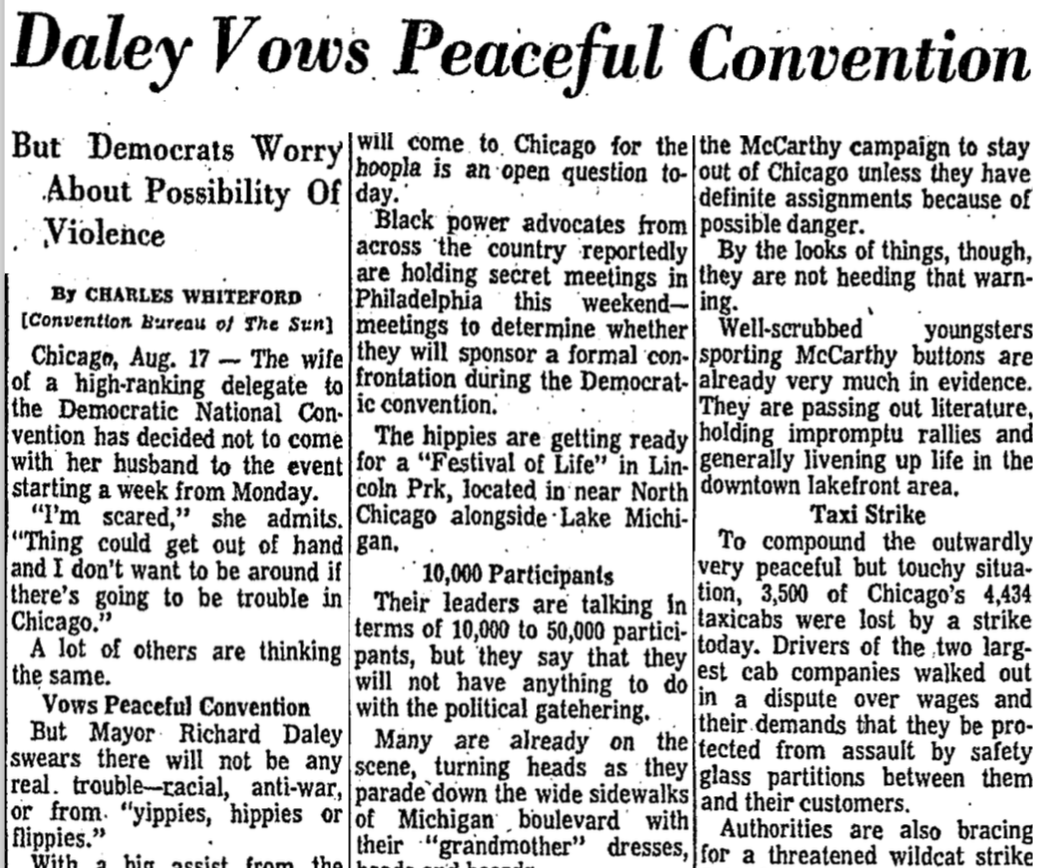

When he heard those rumors, Mayor Daley was not amused.

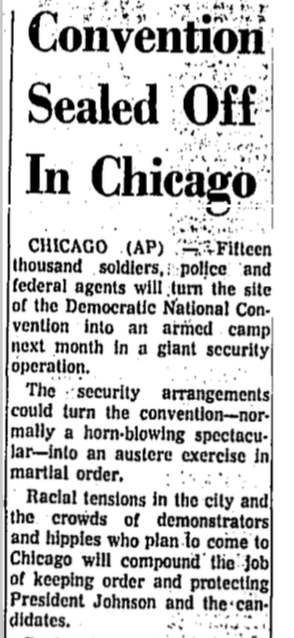

In preparation for the supposed invasion, he mobilized a security force larger than the ones used to quell the massive urban riots in Detroit and Newark the year before.

In preparation for the supposed invasion, he mobilized a security force larger than the ones used to quell the massive urban riots in Detroit and Newark the year before.

All 12,000 of Chicago& #39;s policemen were put on 12 hour shifts. Some 6,000 National Guardsmen were called up, armed with assault rifles, flame throwers and bazookas. At the same time, another 7,500 US Army troops were flown in to stop any potential riot in the black community.

The impending sense of crisis -- and the authorities& #39; assumption that violent confrontation was their only possible response -- set the stage for the "police riot."

But so did the previous year, the previous decade, the previous century.

But so did the previous year, the previous decade, the previous century.

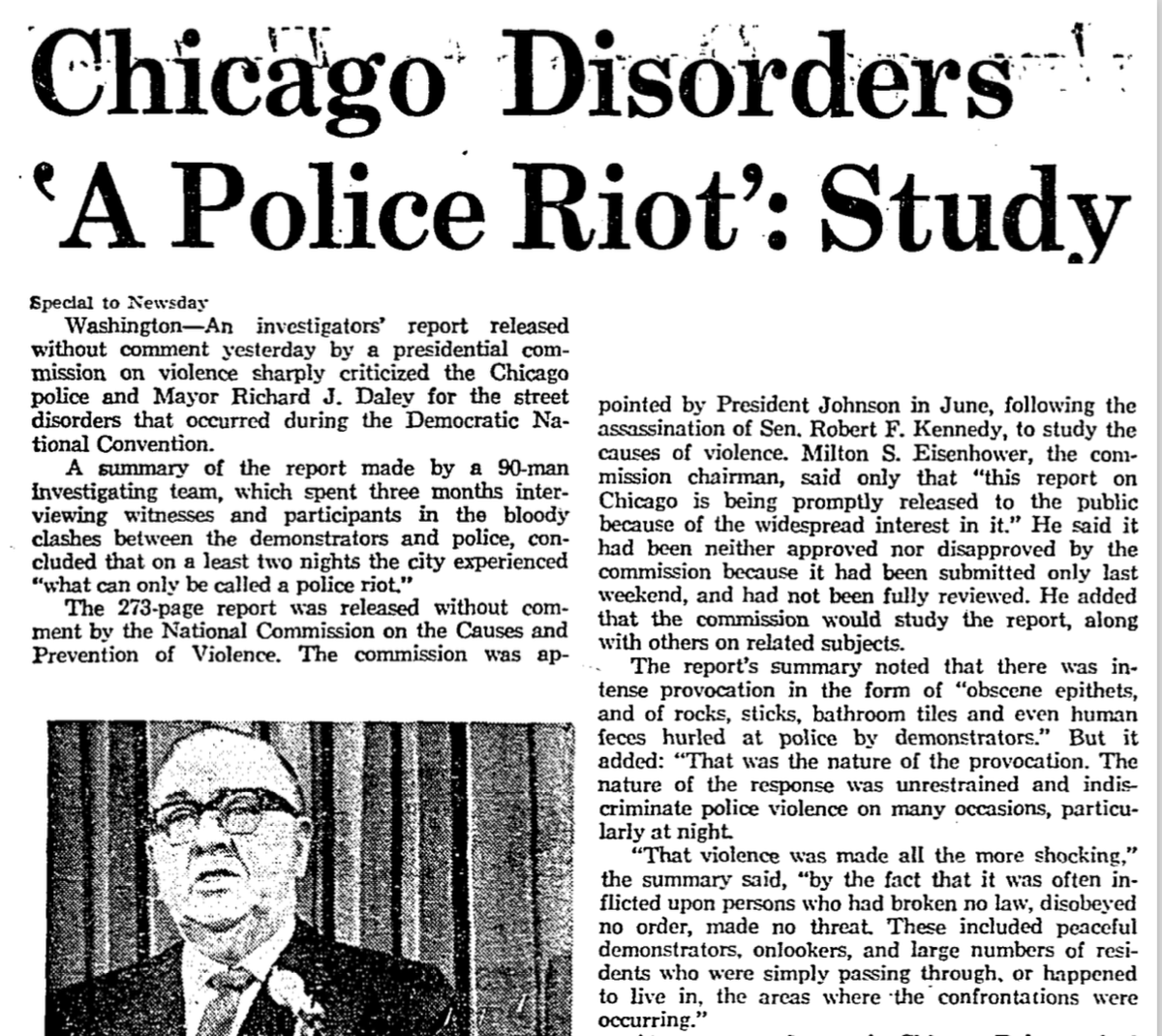

Later that year, an official report classified the convention incident as a "police riot" -- and more important, tried to classify it as something of an aberration, an error to be corrected.

But of course, the legacy of Chicago 1968 wasn& #39;t that it *wasn& #39;t* repeated. It was.

The new politics of "law and order" became a popular model, used from George Wallace to Donald Trump.

Check out @TimLombard0& #39;s book on Philadelphia Mayor Frank Rizzo: https://www.upenn.edu/pennpress/book/15863.html">https://www.upenn.edu/pennpress...

The new politics of "law and order" became a popular model, used from George Wallace to Donald Trump.

Check out @TimLombard0& #39;s book on Philadelphia Mayor Frank Rizzo: https://www.upenn.edu/pennpress/book/15863.html">https://www.upenn.edu/pennpress...

Other politicians adopted a stance of "getting tough" as well.

Read @julillykh& #39;s fantastic book titled after that same popular phrase. https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691174525/getting-tough">https://press.princeton.edu/books/har...

Read @julillykh& #39;s fantastic book titled after that same popular phrase. https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691174525/getting-tough">https://press.princeton.edu/books/har...

Most seriously, other police forces became ever more militarized and ever more prone to respond to peaceful protests with an overwhelming show of force.

Check out @elizabhinton& #39;s fantastic book From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: https://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674979826">https://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.p...

Check out @elizabhinton& #39;s fantastic book From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: https://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674979826">https://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.p...

The problem isn& #39;t that this nation suddenly turned into "Chicago 1968" this week.

The problem is that "Chicago 1968" had been building for a century and only continued to build in the half-century since.

The "police riot" is a national problem. But it long has been.

The problem is that "Chicago 1968" had been building for a century and only continued to build in the half-century since.

The "police riot" is a national problem. But it long has been.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter