In commemoration of the Biafran struggle, I’m posting this recollection of my friend who as a child lived through it.

My Biafran Odyssey by Johnny Mozie

I must have been about 3 years old when we arrived PortHarcourt from England in 1966. My mum & I made the journey by boat

1/

My Biafran Odyssey by Johnny Mozie

I must have been about 3 years old when we arrived PortHarcourt from England in 1966. My mum & I made the journey by boat

1/

My father had stayed back in Yorkshire to tidy up and then join us PortHarcourt, only to be posted to Calabar almost immediately.

My life in Rainbow Town in PortHarcourt was idyllic. My mother’s brothers all had homes on the estate, purpose-built, so very neat and tidy,

2/

My life in Rainbow Town in PortHarcourt was idyllic. My mother’s brothers all had homes on the estate, purpose-built, so very neat and tidy,

2/

what would pass today as a white-picket fence gated community in the West, a middle-class dream.

As time went by, changes were happening around us, including the birth of my cousin Ngozi in January 1967.

I also remember that Achuzie, the Biafran Colonel, also lived on the

3/

As time went by, changes were happening around us, including the birth of my cousin Ngozi in January 1967.

I also remember that Achuzie, the Biafran Colonel, also lived on the

3/

estate with his son. A mixed-race chap slightly older than me at the time, we became fast friends, but alas it only lasted about 6 months before all our lives were to change.

One of my enduring memories of PortHarcourt was meeting Ojukwu. As a child I was taken to meet him

4/

One of my enduring memories of PortHarcourt was meeting Ojukwu. As a child I was taken to meet him

4/

at BMH hospital where my mum worked. He picked me up and placed me on his knees and asked what I would be when I grew up. I didn’t miss a beat as I declared “soldier” to much applause. The applause died when we got home and my mother ‘persuaded’ me to reconsider career choice

The music ended in 1968 when PortHarcourt finally felt the pinch of invading Nigerian forces

I recall leaving our home, setting off on the long trek out of PortHarcourt. My mum tied a few possessions in a wrapper and placed it on her head then tied my cousin Ngozi on her back

5/

I recall leaving our home, setting off on the long trek out of PortHarcourt. My mum tied a few possessions in a wrapper and placed it on her head then tied my cousin Ngozi on her back

5/

with my heavily pregnant aunt in tow, we started the long walk to Aba. My uncles chanced upon us on the trek and we were driven the remaining distance.

There were many families doing the same thing, a human convoy trooping out of PortHarcourt. My uncles who met were ‘combing’

6/

There were many families doing the same thing, a human convoy trooping out of PortHarcourt. My uncles who met were ‘combing’

6/

a term that meant very little to me at the time.

Aba was a very brief interlude, and we fled again after a week or two, further into what was then ‘Bush’. We settled for a long stint in Aguata, where my real wartime education started. I remember that it was in Aguata

7/

Aba was a very brief interlude, and we fled again after a week or two, further into what was then ‘Bush’. We settled for a long stint in Aguata, where my real wartime education started. I remember that it was in Aguata

7/

I was finally introduced to the art of communal eating. Living in a large compound, the women would club together to cook meals which they presented in large pots in the courtyard. All the children gathered and ate out of this pot. The swallow was always too hot, the soup

8/

8/

watery & scalding hot. If you were shy & reserved, finicky about hygiene or particularly averse to crowd eating, you’d starve.

Literally.

And I was, so...

1st night in this strange place, I simply couldn’t. I went home that night & cried for dinner. Mum obliged. Night two,

9/

Literally.

And I was, so...

1st night in this strange place, I simply couldn’t. I went home that night & cried for dinner. Mum obliged. Night two,

9/

she again obliged but gave me a gentle lecture about rationing & joining the communal feeding station as she’d contributed to it.

3rd night I starved.

On day 4, I jostled, blew on my garri, ignored dirty fingers & ate like a native.

I learned to fight, ignored taunts

10/

3rd night I starved.

On day 4, I jostled, blew on my garri, ignored dirty fingers & ate like a native.

I learned to fight, ignored taunts

10/

of ‘oyibo’ and claimed my place. My mum, being the district nurse, had privileged access to Caritas supplies and one of the staples of the time was powdered egg yolk, that came in sachets and was meant to be the egg substitute for fresh eggs. I absolutely hated it.

11/

11/

It became the one and only thing my hungry stomach simply said no to throughout that war.

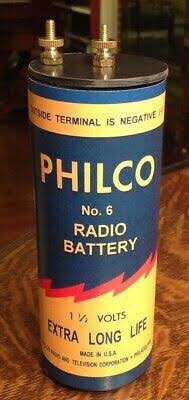

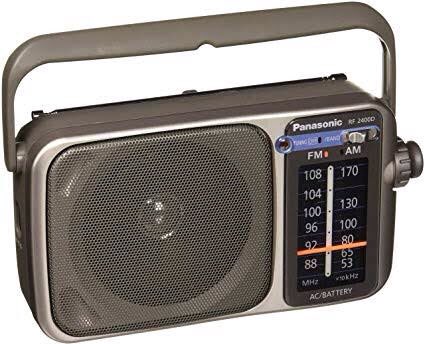

News was at a premium for the adults, and in every compound the adult men gathered around transistor radios tuned low, to listen to BBC world news on what was happening.

12/

News was at a premium for the adults, and in every compound the adult men gathered around transistor radios tuned low, to listen to BBC world news on what was happening.

12/

I remember anger and rage at Nigeria and Britain, murmurs of propaganda at the time. I remember that batteries were also at a premium and people did all sorts of things to keep batteries alive, including sunning them and connecting radio wires to the batteries externally.

13/

13/

White cars were anathema, and many folks found household paint and painted their white cars darker colours so they did not stick out for planes looking for targets.

Nigerian fighter pilots actively and consistently targeted civilian enclaves.

14/

Nigerian fighter pilots actively and consistently targeted civilian enclaves.

14/

On many occasions we’d actually abandon the cars and jump into the bush when caught on the road by air raids.

I learnt to hunt. I was forbidden from eating the coterie of nameless creatures labelled ‘bush meat’ by my mum who’d suddenly turned the cane into

15/

I learnt to hunt. I was forbidden from eating the coterie of nameless creatures labelled ‘bush meat’ by my mum who’d suddenly turned the cane into

15/

an extension of her right hand, but when she was out, I hunted. It was on one of these occasions that we blocked a hole & dug another hunting bush meat. As we dug, Chuchu was designated to put his hand in the hole for the bite that proved we had quarry. He was bitten.

16/

16/

Eventually a big black snake showed and we ran. Chuchu quickly became unwell and I had to tell my mum. Fortunately she had antivenom serum and delivered it to the boy; it saved his life. As for me, I don’t think I sat for a week. That cane. Between the cane and scolding ,

17/

17/

I learnt that no, meant no.

I remember the air raids that left craters all over the village, the sirens that sent us scuttling into bunkers as the jets buzzed overhead; I also remember my mum’s cousin who came to visit. I never saw him again because on his way home,

18/

I remember the air raids that left craters all over the village, the sirens that sent us scuttling into bunkers as the jets buzzed overhead; I also remember my mum’s cousin who came to visit. I never saw him again because on his way home,

18/

his car got bombed.

Wherever you went you saw carcasses of cars & homes either strafed by machine guns or simply bombed.

Car headlights were painted to dim the glow, the men made fuel from all sorts of things.

As all the other cars packed up & died, the Peugeots kept going.

19/

Wherever you went you saw carcasses of cars & homes either strafed by machine guns or simply bombed.

Car headlights were painted to dim the glow, the men made fuel from all sorts of things.

As all the other cars packed up & died, the Peugeots kept going.

19/

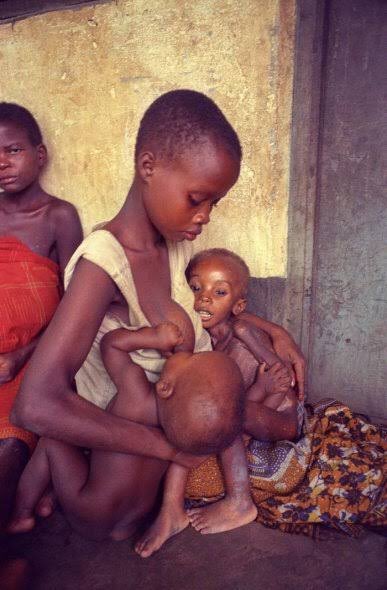

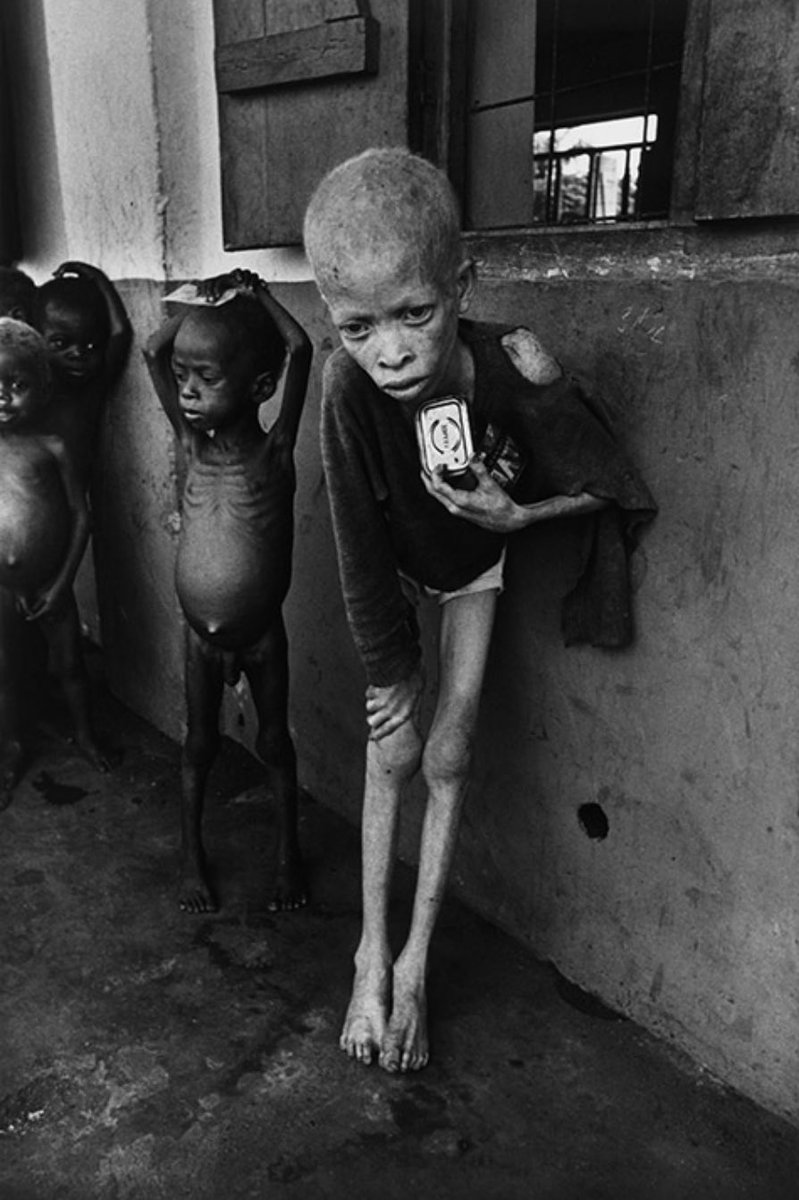

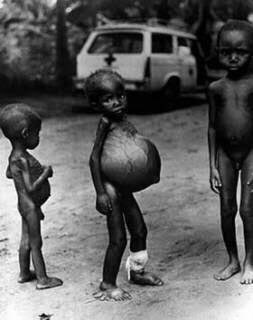

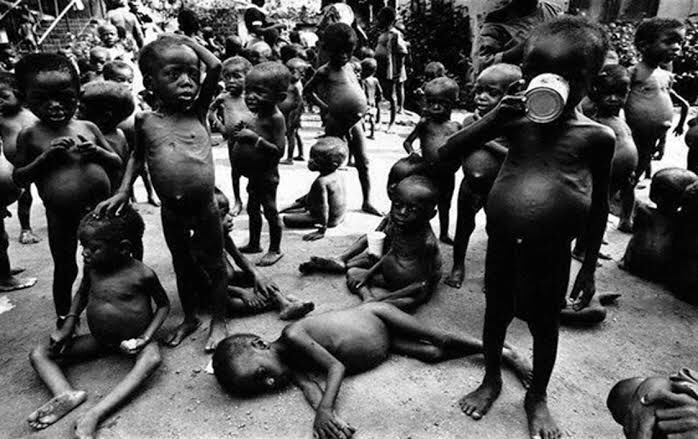

As tough as things were, I now realise I was lucky. Most children around me had protruding stomachs as kwashiorkor took its toll on them, and death was common. If the hunger or bombs didn’t get you, the snakes did. But I was spared the sight of corpses.

20/

20/

As common a sight as it must have been for the adults, the community shielded us kids from it.

It was also in Aguata that I met the python. Fabled and also spoken about in the compound, I never saw it until the night I had diarrhea and had to use the pit latrine.

21/

It was also in Aguata that I met the python. Fabled and also spoken about in the compound, I never saw it until the night I had diarrhea and had to use the pit latrine.

21/

Mum escorted me to one of the pit venues in the compound & waited outside. As I was concluding,I heard a rustling & espied this thing. I screamed. Mum barged in, grabbed me and we ran.

In the morning, some men came & I saw them leave carrying this huge snake like a trophy

22/

In the morning, some men came & I saw them leave carrying this huge snake like a trophy

22/

I went back to the pit and retrieved my short-knickers.

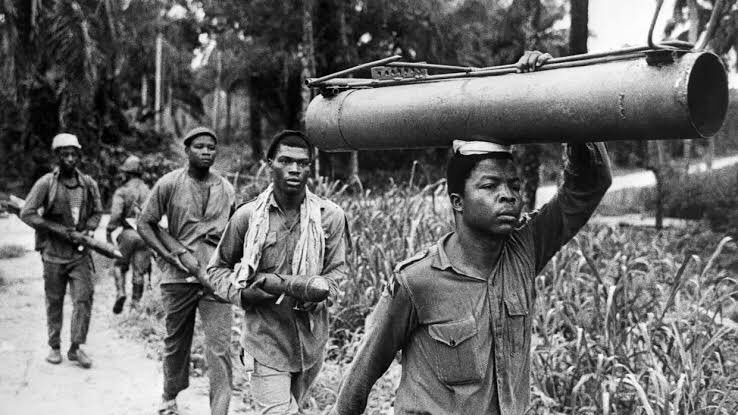

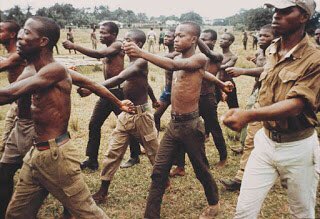

Homes where there were teenage boys were constantly raided by the Biafran army. Older teenagers were conscripted into the army, and you’d see mothers wailing and rolling on the floor as their sons were taken away.

23/

Homes where there were teenage boys were constantly raided by the Biafran army. Older teenagers were conscripted into the army, and you’d see mothers wailing and rolling on the floor as their sons were taken away.

23/

Later families took to hiding their sons in the bush to stop soldiers taking them. We’d also go out to watch the conscripts training, as they jogged singing war songs, holding tree branches and pieces of wood above their heads as if they were rifles.

The Biafran army

24/

The Biafran army

24/

also commandeered people’s vehicles for the “war effort”, another phrase I learnt from the war. However none of my uncles cars were taken, so I presume that this was not as commonplace as perhaps the lack of equipment would suggest.

I recall the bombing of Uli airstrip

25/

I recall the bombing of Uli airstrip

25/

& the consternation that caused amongst the adults, & the anger about Nigerian planes targeting mercy missions bringing relief portions into Biafra.

We eventually fled Aguata for Agulu where we sheltered till the war ended.

Agulu introduced me to udala which was abundant

26/

We eventually fled Aguata for Agulu where we sheltered till the war ended.

Agulu introduced me to udala which was abundant

26/

in the place.

There weren’t as many children in the compound so I was often bored with just my little cousins for company a lot of the time.

We were in Agulu for probably 6 months. I remember going to Christmas Mass there & our first mass family birthday celebration since

27/

There weren’t as many children in the compound so I was often bored with just my little cousins for company a lot of the time.

We were in Agulu for probably 6 months. I remember going to Christmas Mass there & our first mass family birthday celebration since

27/

the war broke out. I have pictures, but even my ebullient sense of sharing has its limits! https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🙈" title="See-no-evil monkey" aria-label="Emoji: See-no-evil monkey">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🙈" title="See-no-evil monkey" aria-label="Emoji: See-no-evil monkey">

In 1969 there was a buzzin the air that the war was ending.

My uncles drove up to Enugu to confirm it was safe.

In 1970, we finally left Agulu for Enugu.

We had survived the war

In 1969 there was a buzzin the air that the war was ending.

My uncles drove up to Enugu to confirm it was safe.

In 1970, we finally left Agulu for Enugu.

We had survived the war

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter

In 1969 there was a buzzin the air that the war was ending.My uncles drove up to Enugu to confirm it was safe.In 1970, we finally left Agulu for Enugu.We had survived the war" title="the war broke out. I have pictures, but even my ebullient sense of sharing has its limits!https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🙈" title="See-no-evil monkey" aria-label="Emoji: See-no-evil monkey">In 1969 there was a buzzin the air that the war was ending.My uncles drove up to Enugu to confirm it was safe.In 1970, we finally left Agulu for Enugu.We had survived the war">

In 1969 there was a buzzin the air that the war was ending.My uncles drove up to Enugu to confirm it was safe.In 1970, we finally left Agulu for Enugu.We had survived the war" title="the war broke out. I have pictures, but even my ebullient sense of sharing has its limits!https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🙈" title="See-no-evil monkey" aria-label="Emoji: See-no-evil monkey">In 1969 there was a buzzin the air that the war was ending.My uncles drove up to Enugu to confirm it was safe.In 1970, we finally left Agulu for Enugu.We had survived the war">

In 1969 there was a buzzin the air that the war was ending.My uncles drove up to Enugu to confirm it was safe.In 1970, we finally left Agulu for Enugu.We had survived the war" title="the war broke out. I have pictures, but even my ebullient sense of sharing has its limits!https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🙈" title="See-no-evil monkey" aria-label="Emoji: See-no-evil monkey">In 1969 there was a buzzin the air that the war was ending.My uncles drove up to Enugu to confirm it was safe.In 1970, we finally left Agulu for Enugu.We had survived the war">

In 1969 there was a buzzin the air that the war was ending.My uncles drove up to Enugu to confirm it was safe.In 1970, we finally left Agulu for Enugu.We had survived the war" title="the war broke out. I have pictures, but even my ebullient sense of sharing has its limits!https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🙈" title="See-no-evil monkey" aria-label="Emoji: See-no-evil monkey">In 1969 there was a buzzin the air that the war was ending.My uncles drove up to Enugu to confirm it was safe.In 1970, we finally left Agulu for Enugu.We had survived the war">