Tooze: “We talk ad nauseam about debt-to-GDP ratios and make complicated calculations of sustainability. But we know shockingly little about to whom we are indebted and where our interest payments actually go.”

Historians against fiscal mystification. A thread.

Historians against fiscal mystification. A thread.

@adam_tooze speaks here to the discomfort many of us feel when “the market” is trotted out to explain why fiscal policy has to be more conservative. Spend less or “the market” will punish us. But who exactly is this “market”?

Vagueness is not helpful. Historians describe structural forces, but we like to find out who exactly delivered the impacts. In the library, with a gun, yes. But was it Colonel Mustard or Miss Plum? Because we have questions.

We want to know “why this and not that?” Without the “who,” we don’t understand the how. And the “why” story is incomplete. Two Canadian crises in tax and debt from the 1930s will illustrate.

4/22

4/22

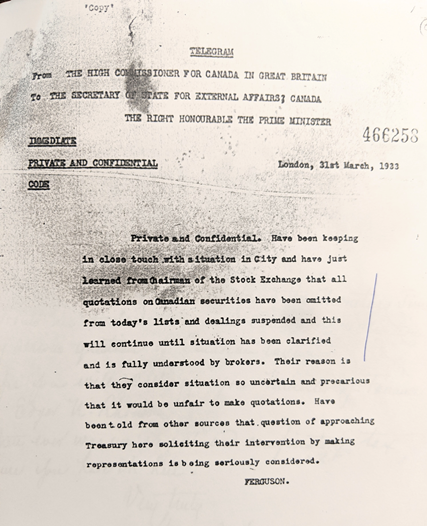

On 31 Mar. 1933, PM Bennett got a telegram saying that trading in Canadian securities had been suspended on the London Stock Exchange. Market discipline!

The 1933 budget had included an unwelcome tax on https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🇨🇦" title="Flag of Canada" aria-label="Emoji: Flag of Canada"> bonds.

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🇨🇦" title="Flag of Canada" aria-label="Emoji: Flag of Canada"> bonds.

London’s brokers found the situation “uncertain” & “precarious.”

The 1933 budget had included an unwelcome tax on

London’s brokers found the situation “uncertain” & “precarious.”

The telegram also said that the City was “seriously” considering asking the Treasury for “interventions” in Canadian law.

(Imperial disallowance on finance matters were still permitted - even after 1931 - under the Colonial Stock Act).

(Imperial disallowance on finance matters were still permitted - even after 1931 - under the Colonial Stock Act).

The telegram came from former Ontario Premier, Canadian High Commissioner G. Howard Ferguson. Ferguson had backed Bennett for the party leadership in 1927. By 1934, Bennett considered Ferguson his possible successor. Ferguson was a ranking political player.

And we know who (Montreal investment banker Ward Pitfield, among others) delivered the message that London wouldn’t tolerate the taxation of “foreigners” who invested in Canada.

In 1935, Pitfield would be one of a group of Canadian financiers who fought for a suspension of party government and elections (“National Government”), so that fiscal prudence would return and investments would be secure.

Knowing the names and biographies matters. They shed light on the politics.

10/22

10/22

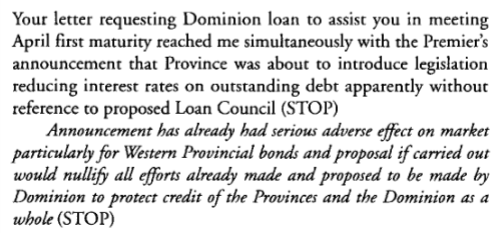

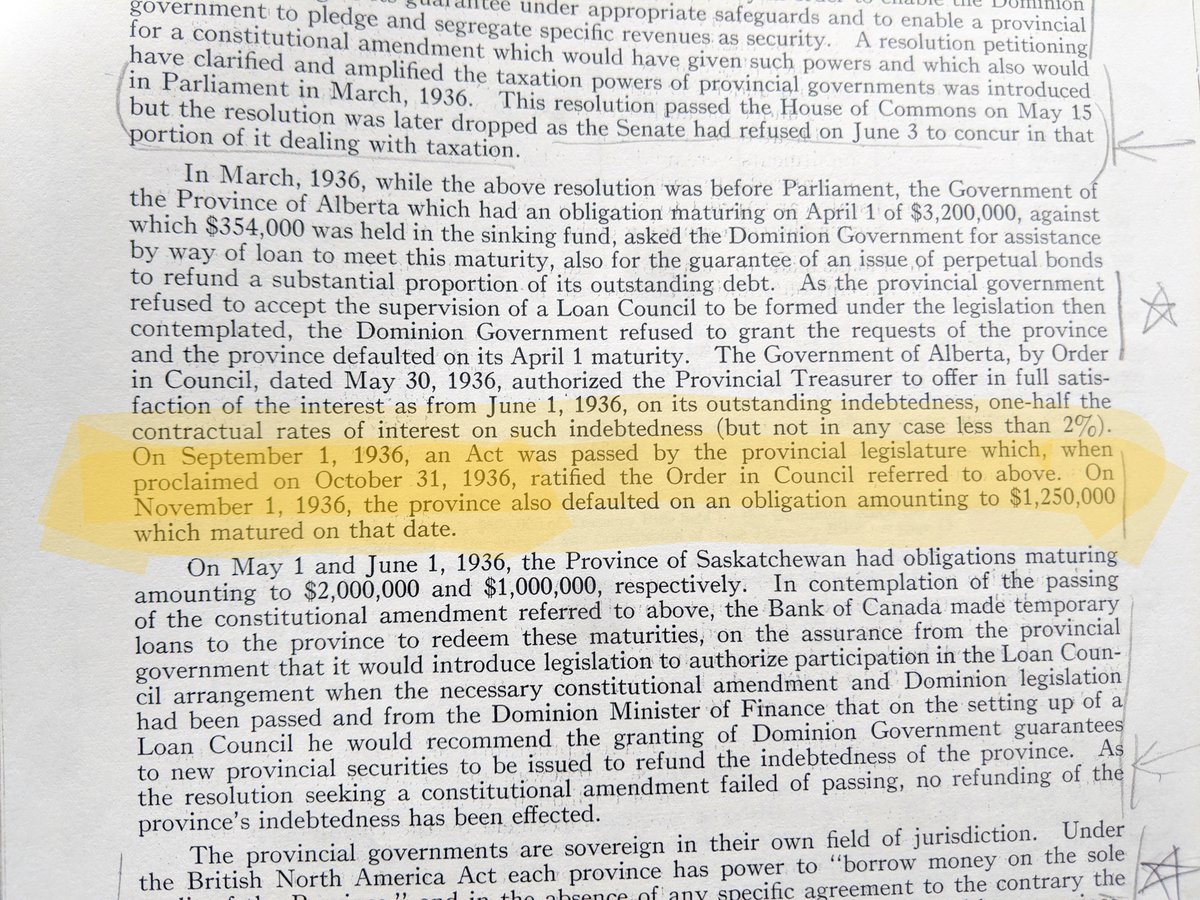

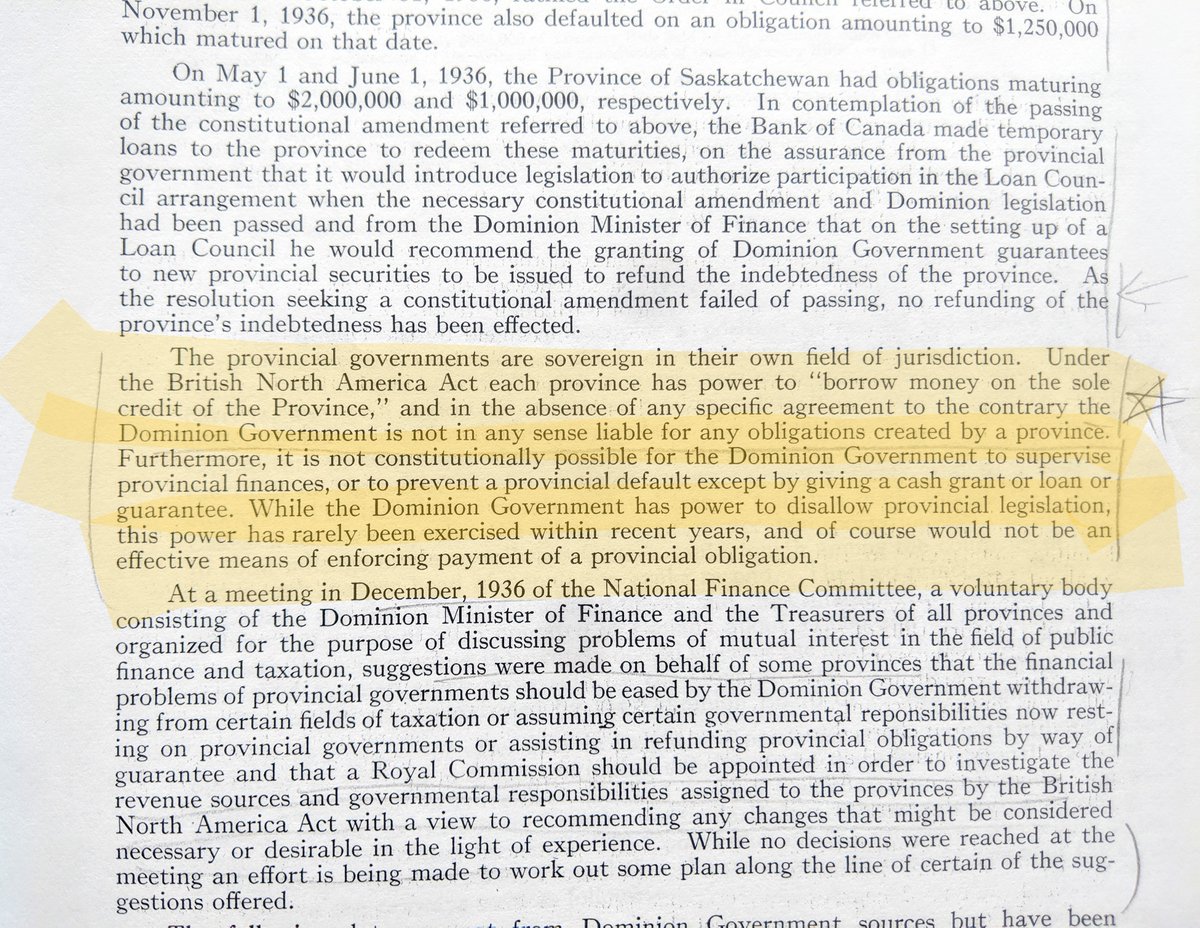

Second example: On 17 Mar. 1936, Finance Minister Charles Dunning pulled the trigger on the province of Alberta – sorry, Premier Aberhart. If you’re going to give investors a haircut, we’re not going to back up your bonds.

Alberta had rejected fiscal tutelage thru a Loan Council. And Dunning had already consulted with the Bank of England’s Montagu Norman about how defaults by western provinces would affect Canada’s credit. Norman urged caution.

And so caution there was. Canada’s prospectus for $85 million bond issue in 1937 included a c.37,000 word statement on the Dominion’s exposure (or lack thereof) to overspending by the provinces. Blow-by-blow on the Alberta default. No constitutional obligation here, folks!

There is more luscious detail on the Alberta story in Robert Ascah’s book on politics and debt. And it *is* politics, not just the inexorable logic of the market. Just as an institution of empire, the Colonial Stock Act, helped “whip the poor colonial into line” in 1933.

Both Ascah and I found smoking guns galore in finance minister’s records and bank archives, documents that show how market actors exercised influence during the 1930s crisis in Canadian public finance.

15/22

15/22

The documents take us beyond the broad brush story of market discipline and supine states. Through them we see the mechanisms of market influence, and also party politics, constitutional interpretations, and public opinion.

16/22

16/22

These public men did not just submit to the market. They manoeuvered, because they were motivated in multiple ways: by norms of justice, by personal ambitions and particular ideas about economic life.

17/22

17/22

Archival research allows historians to see these manoeuvres and motivations. They were often well hidden in their day. But today, these things should not be so well-hidden.

18/22

18/22

Canada, like many other democracies, has made huge progress since the 1930s toward more open government. But to understand the real issues of public finance, we need more than ever the kind of transparency Tooze has called for.

19/22

19/22

Why? Tooze: “to clarify the politics of public debt, to replace fearmongering and bullying with information and serious scrutiny.”

Covid-related debt risks inflicting an epidemic of fiscal mystification. Information is the vaccine.

20/22

Covid-related debt risks inflicting an epidemic of fiscal mystification. Information is the vaccine.

20/22

Sources: This thread draws from the following books. And check out Don Nerbas’s article on Dunning’s personal economist, Gilbert E. Jackson, in the 2013 vol. of Histoire sociale.

21/22

21/22

Thread inspired by https://www.socialeurope.eu/time-to-expose-the-powerful-actors-behind-market-discipline

22/22">https://www.socialeurope.eu/time-to-e...

22/22">https://www.socialeurope.eu/time-to-e...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter