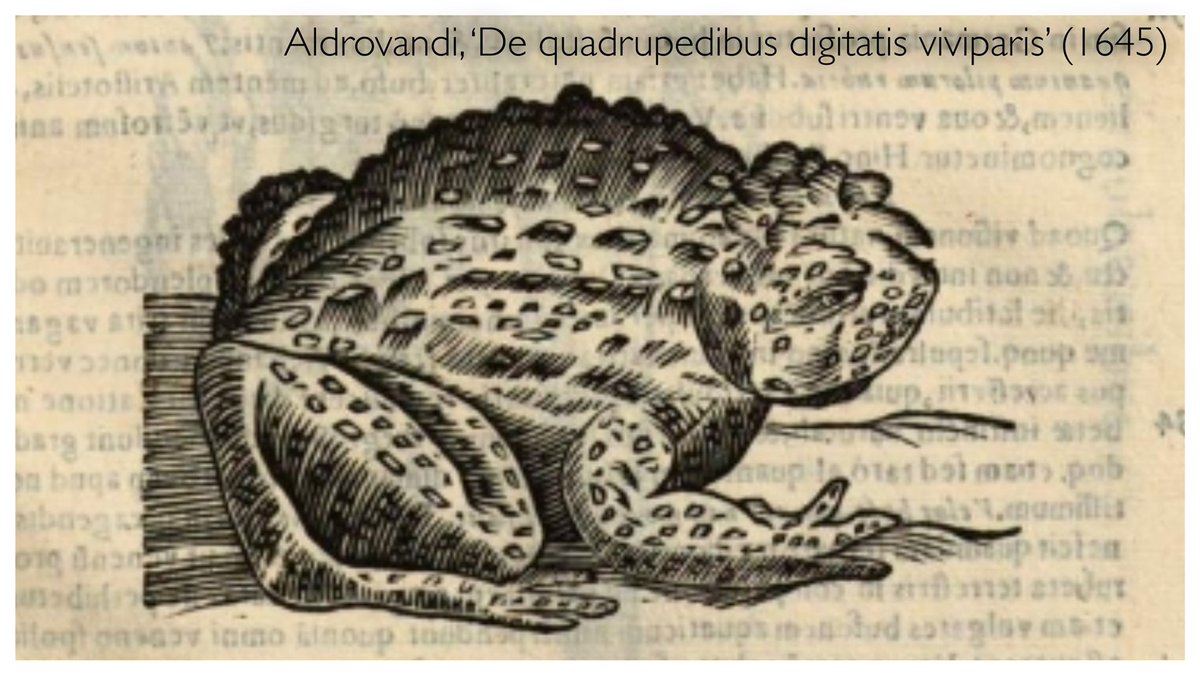

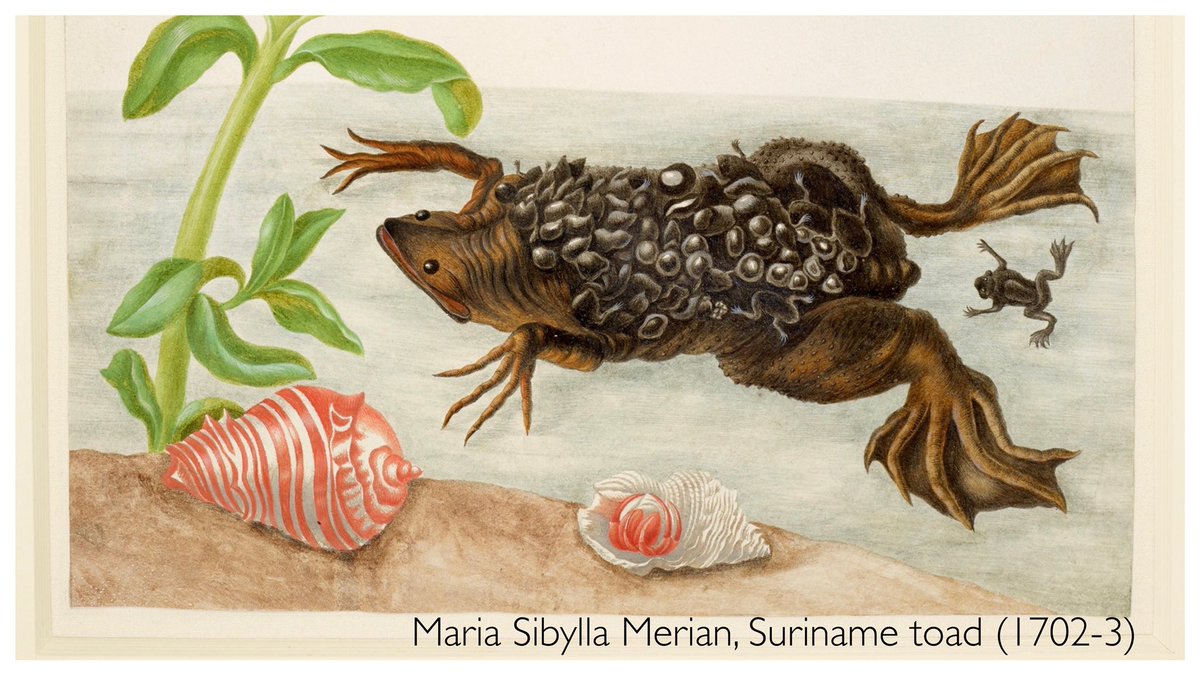

T is for poor old Toad in today’s #LockdownBestiary (aka ‘Paddock’, ‘Crapaud’). Warty, crawling, despised beast, spitting and pissing venom. Classified by Linnaeus with amphibians, ‘foul and loathsome’ animals. The early modern toad had some friends, but mainly enemies ...

Toads barely feature in medieval bestiaries. This 13th-century example, though, has a rubbish toad. But for full medieval horror, Gerald of Wales (c1146–c1223) tells how a plague of toads stalked and killed a sick man, pursuing him up a tree, where they ate up his body.

Edward Topsell has more toad terror (‘History of Serpents’, 1608). A monk woke from an after-dinner nap to find a toad squatting on his lips. His friends, terrified of touching the venomous beast, carried the man to a spider’s web. The spider duly descended and killed the toad.

The spider was said to be the toad’s natural enemy, but in ‘Pseudodoxia Epidemica’ (1646), Thomas Browne recalls putting this to the test. He placed several spiders and a toad in a glass; the spiders crawled over the toad and the toad proceeded to eat them. Victory to the toad.

Loathsome toads gave rise to some world class early modern insults: ‘You Toad-bellied bitch’, ‘poisonous bunch-backed toad’, ‘A most toad-spotted traytor’, ‘Toads-guts, … doe you heare, Monsire?’ (Ford, Shakespeare, Shakespeare again, Rowley).

Milton cast Satan as a toad in & #39;Paradise Lost& #39; (1667), ready to spout venom: ‘Squat like a Toad, close at the eare of Eve’. What could be worse? Nothing was more loathsome than a toad. Unless you were a Whitehall reprobate and sinner. That was worse.

Be careful with the toad insults, though. In 1579 Elizabeth I had John Stubbs’s right hand cut off for his pamphlet arguing against the marriage negotiations between the Queen and Francis, Duke of Anjou and Alençon, in which Stubbs compared the Duke to a venomous toad.

But the venomous toad was not all bad. It contained a great gift in its head, the toadstone, as mentioned in Shakespeare’s ‘As You Like It’: ‘Sweet are the vses of aduersitie / Which like the toad, ougly and venemous, / Weares yet a precious Iewell in his head.’

The toadstone had special powers, including the ability to repel poison. It could be worn as jewel or amulet, or set in a ring. In 1588, Elizabeth I was given a ‘jewell, contayning a crapon or toade-stone set in golde’.

The toadstone’s authenticity was much debated. In 1667 Christopher Merrett revealed it to be fossilized jaw-tooth of a fish.

For more toad trickery, say hello to the ‘toad-eater’ or toady, originally someone employed by a charlatan to eat or pretend to eat toads, thus enabling his master to show off his ‘skill’ in expelling the poison.

Later, ‘toad-eater’ was used perjoratively for a humble female companion: ‘Mrs. Feversham is a toad-eater – women of fashion, when out of spirits ... have half a dozen of such, merely to vent their spleen on before they are seen by their friends.’ (Fanny Burney, ‘Evelina’, 1778).

Women and toads leads nicely to the toad as witch’s familiar. In 1663 Julian Cox was indicted of witchcraft. The tale goes that a neighbour was invited into her house to smoke a pipe only to find a ‘monstrous great toad’ between his legs staring up at him.

In 1605, the servant of the physician Richard Napier didn’t hesitate when he found a toad in the parlour. He picked it up with a pair of tongs and held it in the fire. Napier prayed for the witchcraft to be confounded.

Cf William Harvey of circulation of the blood fame, said to have visited a woman reputed to be a witch. He asked to see her familiar; she put down some milk and out came a toad. Harvey sent her to town for ale and proceeded to dissect the toad, picking it up with a pair of tongs.

Harvey found the toad to be just a toad. The woman returned and was furious. Harvey placated her by saying the King had sent him to arrest her if she were a witch. But the narrator of the tale disputes Harvey’s reasoning: a toad could be both a toad, and sometimes a familiar.

A toad could be tamed and an excellent pet. The toad ‘has been known to become fond of those who treat it with kindness’, as in the story of a Devon toad who for 36 years came into the house of a gentleman every evening to be fed - sadly meeting its demise at the beak of a raven.

That’s all from toads, but it’s not the whole story. Too many toads. Alchemical toads, medicinal toads, toads found alive in stone. Toads born to women, toads born to men, toads brooding basilisks. Do join in with more toadish tales of these shape-shifting resurrection artists.

References: Charlotte Sleigh, ‘Frog’ (Reaktion Books, 2012); Cathy Gere, ‘William Harvey’s weak experiment: the archaeology of an anecdote’, ‘History Workshop Journal’, LI (2001), 19-36; Ruth Salter, ‘Toads mean trouble’ (2016), https://unireadinghistory.com/2016/10/31/toads-mean-trouble/">https://unireadinghistory.com/2016/10/3...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter