Economic Naturalist Question #19. Why are dramatic political shifts so difficult to predict? #EconTwitter

In an earlier thread, I explored why introductory economics courses appear to leave little lasting imprint on the millions of students who take them each year: https://twitter.com/econnaturalist/status/1091461433487953924">https://twitter.com/econnatur...

Students learn more effectively when they pose interesting questions based on personal experience, and then use basic economic principles to help answer them. This exercise became what I call my “economic naturalist” writing assignment.

Many interesting questions are inspired by political events. After decades of stasis and with little apparent warning, political systems sometimes experience revolutionary upheaval. Why are such episodes so rare and so difficult to predict?

As the economist Timur Kuran described in his 1997 book, PRIVATE TRUTHS AND PUBLIC LIES, virtually no political experts foresaw the rapid breakup of the Soviet Union that began in the late 1980s (apart from a few who had predicted its collapse every year for many years).

In Kuran’s account, pundits overestimated the Soviet bloc’s stability largely because most people who lived in member countries voiced consistent support for their leaders in public opinion polls.

But because speaking out against a regime in power entailed obvious risks, polling data were not a reliable measure. Those who support a regime when a pollster asks may merely be trying to avoid those risks.

But there’s safety in numbers. The cost of speaking out depends in part on how many others are also speaking out. Some speak out no matter what, but others are willing to do so only if sufficiently many others join them.

The upshot is that even seemingly minor provocations or small changes in the odds of punishment can unleash a prairie fire of unexpected public opposition—first, by inducing a few additional people to speak out, which then induces still others to do so, and so on.

Dynamic processes like these often culminate in near complete reversals of public opinion. They explain why big changes sometimes happen so quickly and with so little forewarning.

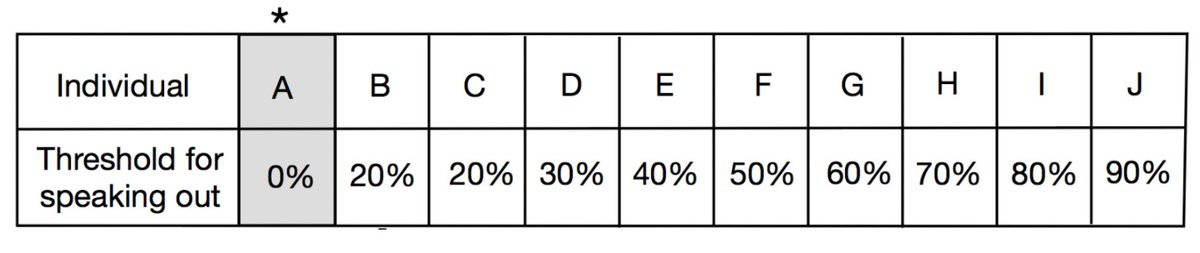

An example: imagine a population consisting of 10 citizens—call them A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, and J—who live under an authoritarian regime that they would oppose publicly if they thought it safe to do so.

Each has a threshold indicating his or her willingness to speak out as a function of how many others are speaking out. A, for example, is a radical who’s willing to speak out no matter what.

B and C are only slightly more cautious, each willing to speak out if at least 20 percent of their fellow citizens are also speaking out.

The remaining citizens have higher thresholds, as summarized in the table below. Citizen A, by assumption, will speak out irrespective of what others do. But A constitutes only 10 percent of the population, and that’s below the threshold of each of the others.

All but A will therefore remain silent. The stable outcome in this situation, indicated by the asterisk above the shaded entries in the table, is that only one in 10 citizens speak out. The regime survives. But now suppose something causes B to become less cautious.

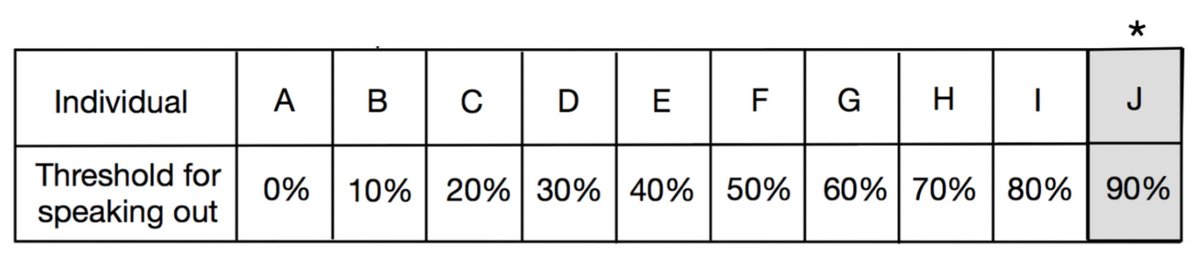

Perhaps he is emboldened by news accounts describing how German dissidents suffered no consequences when they dismantled the Berlin Wall. Or perhaps he or a family member has suffered in some unexpected way from an action by the regime.

Whatever the cause, B’s threshold for speaking out falls from 20% to only 10%, as indicated below. Since A is already speaking out, B’s slightly lower new threshold is now met, so he too speaks out, in the process raising the percentage of citizens speaking out to 20.

This makes C willing to speak out as well, pushing the percentage to 30. E then starts speaking out, raising the percentage speaking out to 40, and so on.

In short order, a small change affecting only B causes the percentage of the population speaking out against the regime to rise from only 10 percent to 100 percent, again as indicated by the asterisk above the shaded entries in the table. This time, the regime topples.

Is the US on the cusp of dramatic political change? It feels like it. But it has felt that way before. Behavioral contagion helps explain why it is so hard to predict whether this time is different. But it also explains why change, when it happens, will happen quickly.

As I discuss in UNDER THE INFLUENCE: PUTTING PEER PRESSURE TO WORK, behavioral contagion has dramatic implications not just for the possibility of dramatic political change, but also for how to battle climate change, inequality, and viral pandemics.

https://www.amazon.com/Under-Influence-Putting-Peer-Pressure/dp/0691193088">https://www.amazon.com/Under-Inf...

https://www.amazon.com/Under-Influence-Putting-Peer-Pressure/dp/0691193088">https://www.amazon.com/Under-Inf...

Ezra Klein and I discuss many of the ideas from the book in the most recent episode of his podcast, which he has entitled "Robert Frank& #39;s Radical Idea": https://www.vox.com/podcasts/2020/5/26/21269556/robert-frank-under-the-influence-ezra-klein-show-coronavirus">https://www.vox.com/podcasts/...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter