A brief thread, since if hating on the American classic "A Separate Peace" didn& #39;t get me cancelled, then this political commentary probably won& #39;t... (1)

Slate Star Codex published this well-known post in 2014 about divisions between & #39;blue& #39; and & #39;red& #39; communities. I think a lot of it was good, although the major Achilles heel was that his *entire* discourse was centered around wealthy communities... (2) https://slatestarcodex.com/2014/09/30/i-can-tolerate-anything-except-the-outgroup/">https://slatestarcodex.com/2014/09/3...

...i.e. he lists "arugula" and "fancy bottled water" under the Blue archetype and "SUVs" under the Red one. He attributes political agency only to the wealthy, but then doesn& #39;t engage with that notion of wealth as the playmaker of American politics at all. (3)

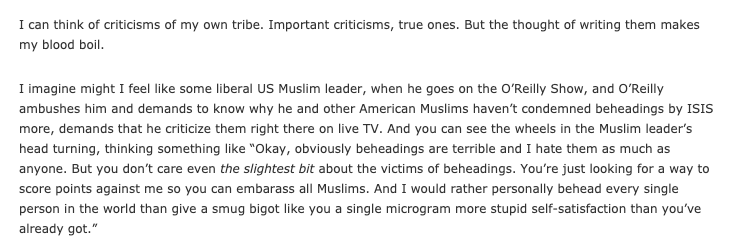

But he does make one point about outgroup criticism that I think is important and understudied. After saying, essentially, that critiquing one& #39;s own tribe is really difficult and blood-boiling, which is true, he provides the following *extremely* sympathetic vignette: (4)

I think this is an important and relatable psychological phenomenon underscoring contemporary American discourse. Not just the fact that self-criticism is hard, but the feeling that people from the other side of the aisle who ask us to self-criticize have bad motivations. (5)

What SSC says here--"You don& #39;t care even the SLIGHTEST bit about [X]"--is the final explainer, I think, of the rancor. It& #39;s not about the failure of the other side to see the issues we think are important... (6)

..it& #39;s that we identify the other side as weaponizing things that we *of course* also think are important in order to discredit or obfuscate things that we think, for whatever reason, deserve more attention in the now. (7)

In the case SSC describes, the leader is insulted both by the accusation that he doesn& #39;t care about an important issue and by the feeling that the issue is being used thoughtlessly, or instrumentalized, against him--it is being depleted of its importance and meaning. (8)

This explains why leftists are being driven nuts by the media& #39;s focus on the Minneapolis riots right now, and why rightists are being driven nuts by being called racist or being accused of not caring about police brutality. (9)

Neither of these accusations are true. Nor, furthermore, is the fact that you have to pick one--order or justice, liberty or equal standing, solidarity or tolerance. It is a productive political illusion. In particular, it& #39;s useful for making the two major parties... (10)

...have a "big-tent" feel. (Which is essentially the phenomenon SSC describes.)

I think the big-tent phenomenon is dead or dying. Trump has irreparably divided the GOP, and the bizarre behavior of the Dem establishment these past few weeks has done the same for the Dems. (11)

I think the big-tent phenomenon is dead or dying. Trump has irreparably divided the GOP, and the bizarre behavior of the Dem establishment these past few weeks has done the same for the Dems. (11)

But while big-tentism existed, it was primarily founded upon the sacred doctrine of the Well-Ordering of Bad Things. (12)

Your political allegiances were determined not absolutely, but relatively. Out of a certain slate of things, which do you care MORE about than others? "Freedom or equality" is, I think, the big one, but this phenomenon pervades EVERY definition of political affiliation. (13)

The budget is the Platonic form of this, because it& #39;s very clearly a zero-sum game. Any money that goes to the arts can& #39;t go to the military. Things have to be ranked. (14)

But the notion that *everything* is a trade-off seems more straightforwardly false. To get a little decision-theoretic, what& #39;s at play here is whether maximality is the same as optimality. (15)

Under sum-ranking utilitarianism and expected utility theory, maximizing is a simple procedure. There is one axis of unity along which we seek to maximize. Therefore, anything can be compared with anything else. (16)

Even under assumptions of uncertainty and state-dependent utility, we can deduce a well-ordering that is robust. (Cardinals, no, but that would be more than we& #39;d need.) But it& #39;s not just sum-ranking. A lot of choice rules admit of this property. (17)

The Rawlsian leximin, for instance: assuming a whole bunch of people, maximize the utility of the worst-off person. This always allows us to well-order the space of possibilities, because we& #39;re only ever comparing one thing, one utility value. (18)

The notion that any things can be compared drives us into trouble if resources are finite. Under non-ideal circumstances, things HAVE to be compared. I HAVE to choose between resource distributions or budget allocations. There& #39;s not enough for everything to be satisficed. (19)

The decision-procedural ethos underpinning the moral panic phenomenon we have right now, I think, is that this well-ordering is perceived as absolute rather than relative. Being able to rank two things is parsed as not caring about the lower-ranked thing. (20)

On the TL recently, this has been taken absurdly far. Remember that rant about how Anne Frank deserves no sympathy? The fact that a lot of discourse is (rightfully) given to the Holocaust was taken as ranking other genocides lower, and thus not caring about them. (21)

And then Conservative Twitter had that insane discussion: "Is OnlyFans worse than living under an Islamic caliphate?" The only appropriate response to such a question is to reject its premise. Why would something like that be asked? (22)

Because people have forgotten that we are allowed to reject the premise of such questions--that doing so is not a trick or an escape. Refusal to engage with the sacred Cost Benefit Analysis is not playing 5D chess. (23)

There are nonstandard aggregation methods and decision theories that do not require us to strictly sum-rank, that do not provide a well-ordering, that occasionally violate Sen& #39;s alpha and beta. These methods exist. (24)

Isaac Levi& #39;s decision theory is not transitive. (GASP!) Martha Nussbaum& #39;s sufficientarian calculus does not provide a criterion for always deciding which of two worlds is better. (25)

Lara Buchak& #39;s (inspired) decision theory is not "consistent," i.e. you can get Dutchbooked. (26)

These are not mainstream techniques, and the arguments leveled against them are some form of "They& #39;re not well-orderings," "They& #39;re not transitive," "They violate IIA," and therefore they& #39;re not normatively useful. (27)

But those arguments have always struck me as begging the question. They assume the premise they& #39;re trying to prove: that theories that do not uniquely well-order the choice set are not normatively useful. (28)

I don& #39;t want to go down a rabbit hole of arguing that "ought" does not actually imply "can." That& #39;s more than I need here. What I need is that "preferable" does not imply "better." (29)

The ethos underpinning a theory like Nussbaum& #39;s (or, my interpretation of it) is that no world where ANY individual has full capabilities is acceptable. Could I pick between bad worlds? I mean, yeah, if I had to--but that cannot be taken as a moral statement of "worse." (30)

My humble suggestion is that political discourse should take Nussbaum, rather than Rawls or EUT, as its basis of sensibilities. Prioritizing something should neither be seen as not caring about the other thing, nor even thinking the other thing isn& #39;t *as* important. (31)

For instance, I might just prioritize a problem because I think it& #39;s more solvable or that I& #39;m better at it. EA& #39;s not perfect, but one thing I love about it is that it makes this decision basis normative--picking something doesn& #39;t mean thinking it& #39;s of greater moral worth. (32)

The other dimension here is the interpersonal one. ("Why won& #39;t you condemn Y?" "Of course I hate Y as much as anyone--but YOU& #39;RE only asking me that to get me to demote X, which I have preferenced over Y.") (33)

There are two separate bad faith things going on here. The talk show host assumes the guest doesn& #39;t care about Y--and then the guest assumes the host doesn& #39;t care about *either* X or Y. (34)

I maintain that we can solve both of them by having a different ethos of decision-making. But I think the second phenomenon deserves independent consideration. I& #39;ll blog about it later or something. (35/Fin)

Oh, the Libertarian/Paretian divide is another good example I should have mentioned in this thread.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter