My thread yesterday about Islamic responses to antiquity provoked lots of great conversation, so I thought I& #39;d do a follow-up thread to clarify a few points. I& #39;m grateful for people who ask interesting questions that make me think more deeply! https://twitter.com/Tweetistorian/status/1265436893422014465">https://twitter.com/Tweetisto...

The majority of comments responded to an admittedly provocative statement: "there is no precedent in Islamic history for their (ISIS& #39;) actions". I stand by that, but it deserves some explanation. I could have been a bit clearer in my wording. TWITTER SCHOLARSHIP IS HARD Y& #39;ALL

Responses fell into three broad categories:

1. Muhammed destroyed the idols in the Kaaba in Mecca

2. What about the Bamiyan Buddhas?

3. Muslims destroyed temples and temple sculpture in India

1. Muhammed destroyed the idols in the Kaaba in Mecca

2. What about the Bamiyan Buddhas?

3. Muslims destroyed temples and temple sculpture in India

I& #39;ll respond one by one, and explain why what ISIS was doing was different than any of these prior examples.

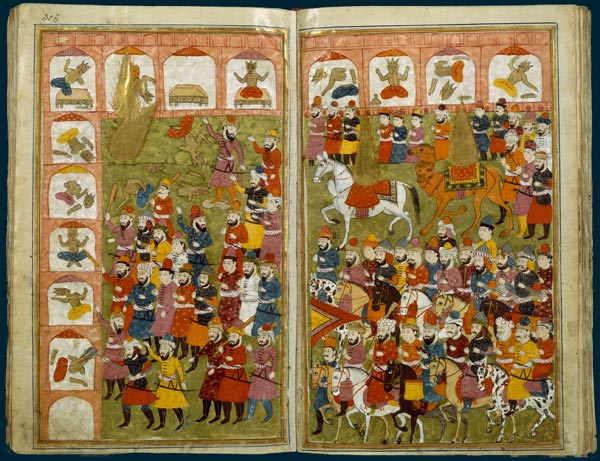

1. One of the famous episodes of Muhammad& #39;s prophetic career was his "cleansing" of the Ka& #39;ba of idols upon his return to Mecca in 629-30. http://expositions.bnf.fr/parole/grand/sup-pers_1030_305v-306.htm">https://expositions.bnf.fr/parole/gr...

1. One of the famous episodes of Muhammad& #39;s prophetic career was his "cleansing" of the Ka& #39;ba of idols upon his return to Mecca in 629-30. http://expositions.bnf.fr/parole/grand/sup-pers_1030_305v-306.htm">https://expositions.bnf.fr/parole/gr...

Muhammad was deeply concerned about the place of Islam within the older traditions of Abrahamic monotheism - Abraham, too, had destroyed idols and had built the Ka& #39;ba. Abraham Destroying Idols, from al-Athar al-Bakiyya of al-Biruni, Edinburgh University Library (MS. Arab.161)

But Muhammad& #39;s actions were pretty specific: he destroyed idols representing deities that were actively worshiped inside a religious sanctuary. And he was also somewhat selective. For example, he didn& #39;t destroy the Black Stone and he preserved an image of Mary and Jesus.

And in the Hadith, we read of the Prophet being worried about wall hangings bearing figural representations, but allowed the same fabrics to be used as pillows. This tells us that even in the Prophet& #39;s time, there was room for interpretation as to what constitutes idolatry.

From this, we can surmise that early Muslims distinguished between images that appeared in contexts that made them likely to be the focus of worship (i.e. inside religious sanctuaries) and images that were more likely not to be worshiped (pillows on the ground).

And as I mentioned yesterday, Islamic art is full of figural imagery, including statues and even images of the Prophet Muhammad himself. The key distinction is that images tend not to appear in religious contexts like mosques, which are typically aniconic. https://twitter.com/stephenniem/status/927530813989769222?lang=en">https://twitter.com/stephenni...

And this is what makes ISIS& #39; actions so aberrant. Muhammad was destroying the religious idols of deities that were actively worshiped by the Meccans. ISIS destroyed statues of long-dead ancient kings whose names few remember. Do you know the kings of Hatra?

No? Don& #39;t worry, I only vaguely did before ISIS. https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😟" title="Worried face" aria-label="Emoji: Worried face">Here& #39;s the magnificent Hatran King Sanatruq, (Iraq Museum, Baghdad, 1st-3rd c). This is what ISIS destroyed. But that interpretation - that statues of ancient kings were to be viewed as idols and destroyed - is new, is modern.

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😟" title="Worried face" aria-label="Emoji: Worried face">Here& #39;s the magnificent Hatran King Sanatruq, (Iraq Museum, Baghdad, 1st-3rd c). This is what ISIS destroyed. But that interpretation - that statues of ancient kings were to be viewed as idols and destroyed - is new, is modern.

That& #39;s not to say there was no "idol anxiety" in Islamic culture prior to ISIS. There was (just as there was in Christianity and Judaism), but attitudes are fluid and change over space and time. The Umayyad Caliphs, for example, loved their statues. https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-islam/chronological-periods-islamic/islamic">https://www.khanacademy.org/humanitie...

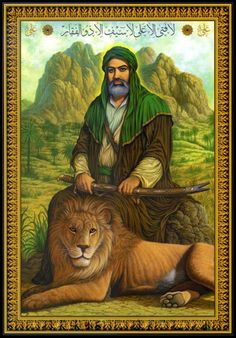

And Shi& #39;ism has a rich tradition of figural imagery, even of holy figures. Contrary to ISIS& #39; argument, Islamic thought has never been static or fixed, but has always been a vast, ever-changing ocean of discourse. Ideas about images are part of that.

Popular image of Imam & #39;Ali

Popular image of Imam & #39;Ali

So where did ISIS get their playbook? From Wahhabi Salafism, an early modern religio-political movement that began in the 18th c. in Arabia and which still forms the foundation of the Saudi state& #39;s official religious policies. https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780195390155/obo-9780195390155-0091.xml">https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/docu...

This is why claims that ISIS espouses a "medieval" ideology ring hollow. Everything al-Qaeda and ISIS represent is the product of modernity. In fact, to believe otherwise is to buy ISIS& #39; own propaganda. If you& #39;re puzzled, I recommend this book highly! https://thenewpress.com/books/al-qaeda-what-it-means-be-modern">https://thenewpress.com/books/al-...

But in Islam, as far as I& #39;m aware, there are few premodern precedents for the ideological destruction of secular figural imagery on grounds that they are "idols", and thousands of such sculptures survived into the present, in every Islamic land. Palmyrene sculpture, Syria, 3rd c.

So the Prophet distinguished between religious idols and secular images, there& #39;s little evidence Muslims viewed images of kings as idols, and later Muslims produced figural imagery (including statues and religious images) for over 1,400 years. But what about the Bamiyan Buddhas?

That story, too, is complex. In fact, the Buddhas of Bamiyan were initially slated for preservation by the Taliban, in hopes of generating tourist revenue. According to Mullah Omar himself, they were only destroyed to get Western media attention. https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ap-art-history/west-and-central-asia-apahh/central-asia/a/bamiyan-buddhas">https://www.khanacademy.org/humanitie...

In a 2004 interview Mullah Omar said that Westerners cared more for ancient stones than starving Afghan children. The destruction of the Buddhas was meant to bring attention to what he viewed as Western hypocrisy, not make a religious point about idolatry. https://www.rediff.com/news/2004/apr/12inter.htm">https://www.rediff.com/news/2004...

In other words, the Taliban& #39;s motivations were not primarily religious or theological in nature. To be sure, destroying the Buddhas fit into their Wahhabi-inspired worldview - but the primary motivation was not to "destroy idols" - as it was with ISIS.

Lastly, what about India? Many commentators argued that Islam had a long record of destruction in India, particularly of Hindu temples. Hindutva, like all modern nationalist ideologies (including ISIS) favors simple binaries. But again, the reality is far more complex.

There were absolutely examples of destruction by Muslims of pre-Islamic sites in India. Conquest is violent, and ideology is often put to use to achieve its ends. But can we determine a systematic pattern, deployed over centuries, of Muslim destruction? That& #39;s more difficult.

If we look at the era from the earliest Islamic dynasties in India in the 12th century through the Mughal period, there& #39;s also abundant evidence of preservation, curiosity, and respect. Iron Pillar of Hindu King Chandragupta II, inside the Quwwat al-Islam Mosque, Delhi, 1192

As Santhi Kavuri-Bauer has argued in my @IJIA2012 volume on antiquity in Islamic societies, Muslim rulers reused columns not as victory monuments - they were incorporated into complex Islamic strategies of kingship that drew on ideas about & #39;ajab or wonder. https://archnet.org/collections/1710/publications/13383">https://archnet.org/collectio...

And @AudreyTruschke has shown that Aurangzeb preserved more temples than he destroyed. https://theprint.in/features/aurangzeb-protected-more-hindu-temples-than-he-destroyed-says-historian-audrey-truschke/95145/">https://theprint.in/features/...

The Mughal Emperor Akbar, famed for his religious ecumenism, sponsored editions of the Ramayana in Persian.

https://scroll.in/article/684556/eight-exquisite-mughal-miniatures-of-the-ramayana-commissioned-by-emperor-akbar">https://scroll.in/article/6...

https://scroll.in/article/684556/eight-exquisite-mughal-miniatures-of-the-ramayana-commissioned-by-emperor-akbar">https://scroll.in/article/6...

Just a handful of examples of a long and complex tradition of interaction around objects and images between Muslims and others in India. So this story, too, is difficult to reduce to a simple binary of destruction vs. preservation. The real story is far more interesting.

And so to come full circle, I stand by my comment that what ISIS did had very few, perhaps even no precedents in Islamic history. The justification of destruction of secular monuments in the name of Islam is a wholly new phenomenon. Let& #39;s hope it goes the way of history.

If this thread got you curious about the history of figural imagery in Islam in general, you& #39;re lucky, because my brilliant colleague Christiane Gruber has just published a summary of her work on this topic. Very much indebted to her! https://www.academia.edu/42914508/Idols_and_Figural_Images_in_Islam_A_Brief_Dive_into_a_Perennial_Debate">https://www.academia.edu/42914508/...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter

Here& #39;s the magnificent Hatran King Sanatruq, (Iraq Museum, Baghdad, 1st-3rd c). This is what ISIS destroyed. But that interpretation - that statues of ancient kings were to be viewed as idols and destroyed - is new, is modern." title="No? Don& #39;t worry, I only vaguely did before ISIS.https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😟" title="Worried face" aria-label="Emoji: Worried face">Here& #39;s the magnificent Hatran King Sanatruq, (Iraq Museum, Baghdad, 1st-3rd c). This is what ISIS destroyed. But that interpretation - that statues of ancient kings were to be viewed as idols and destroyed - is new, is modern." class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

Here& #39;s the magnificent Hatran King Sanatruq, (Iraq Museum, Baghdad, 1st-3rd c). This is what ISIS destroyed. But that interpretation - that statues of ancient kings were to be viewed as idols and destroyed - is new, is modern." title="No? Don& #39;t worry, I only vaguely did before ISIS.https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😟" title="Worried face" aria-label="Emoji: Worried face">Here& #39;s the magnificent Hatran King Sanatruq, (Iraq Museum, Baghdad, 1st-3rd c). This is what ISIS destroyed. But that interpretation - that statues of ancient kings were to be viewed as idols and destroyed - is new, is modern." class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>