Five years and three months ago today, ISIS entered the museum in Mosul and began to destroy ancient statues with pickaxes and sledgehammers. They claimed they were destroying "false idols" in the name of Islam. In fact, there is no precedent in Islamic history for their actions.

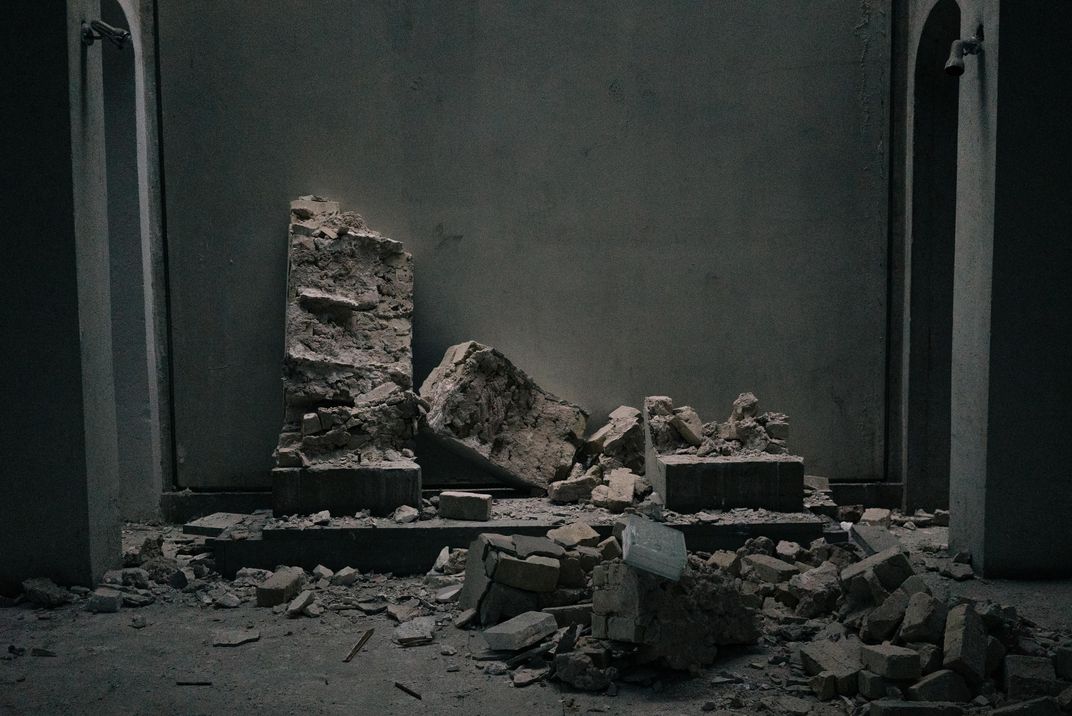

A few months later in July of 2015, they would begin a campaign of destruction at Syria& #39;s most famed ancient site - Palmyra. Before it was over, ancient tomb towers, temples, and the famous Triumphal arch (seen here in 2009) would lie in ruin.

But that& #39;s only part of the story.

But that& #39;s only part of the story.

Syrian archaeologists, like Khaled al-Asaad, worked around the clock to save Palmyra. He would eventually give his life in defense of the site. His actions evoke the real history of how people in Islamic lands have related to antiquity over time: with curiosity, awe and respect.

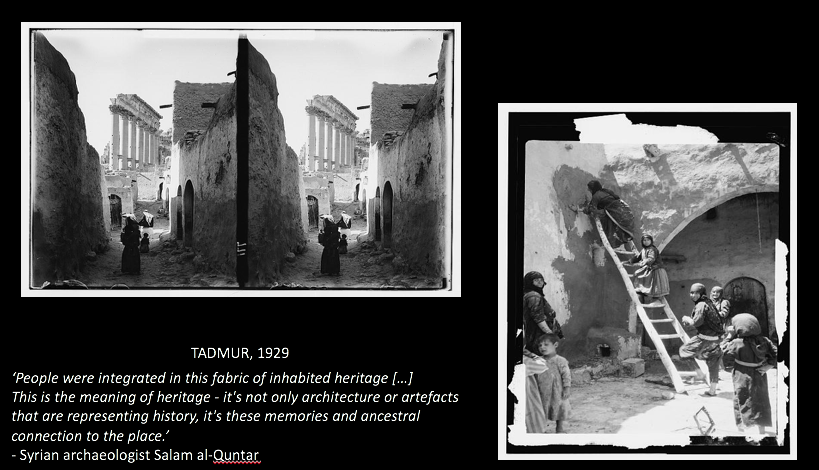

The ISIS moment also obscures other histories of destruction at Palmyra. In 1929-30, French Mandate archaeologists systematically dismantled the living town of Tadmur that surrounded the Temple of Bel - a town that probably dated back to ancient times. Image: @ifporient

At the center, inside the Temple of Bel, was a mosque, previously a church, where residents had worshiped for almost two millennia.

The Temple of Bel had been a temple for a mere 260 years. Yet the French archaeologists chose the temple.

Getty Research Institute (2015.R.15)

The Temple of Bel had been a temple for a mere 260 years. Yet the French archaeologists chose the temple.

Getty Research Institute (2015.R.15)

That Palmyra and thousands of sites like it survived for millennia tells us something about how people in Islamic lands have encountered and engaged with sites of antiquity. Though these heritage ideals don& #39;t always align exactly with modern ones, these sites were clearly valued.

So what can we know? In a 2017 special issue of @IJIA2012, I argued that there were four broad categories by which we can begin to conceptualize an "Islamic" notion of ancient heritage: & #39;Ajab (wonder); ‘Ibar (as lessons); Talismanic/Apotropaic uses, and Sacred Histories.

The notion of ‘ajab or wonder, an overpowering feeling of astonishment and awe at encountering things that are strange, ancient, extraordinarily beautiful or marvelous, had developed into a distinct genre of Arabic and Persian literature, called the ‘aja’ib, by the 10th c.

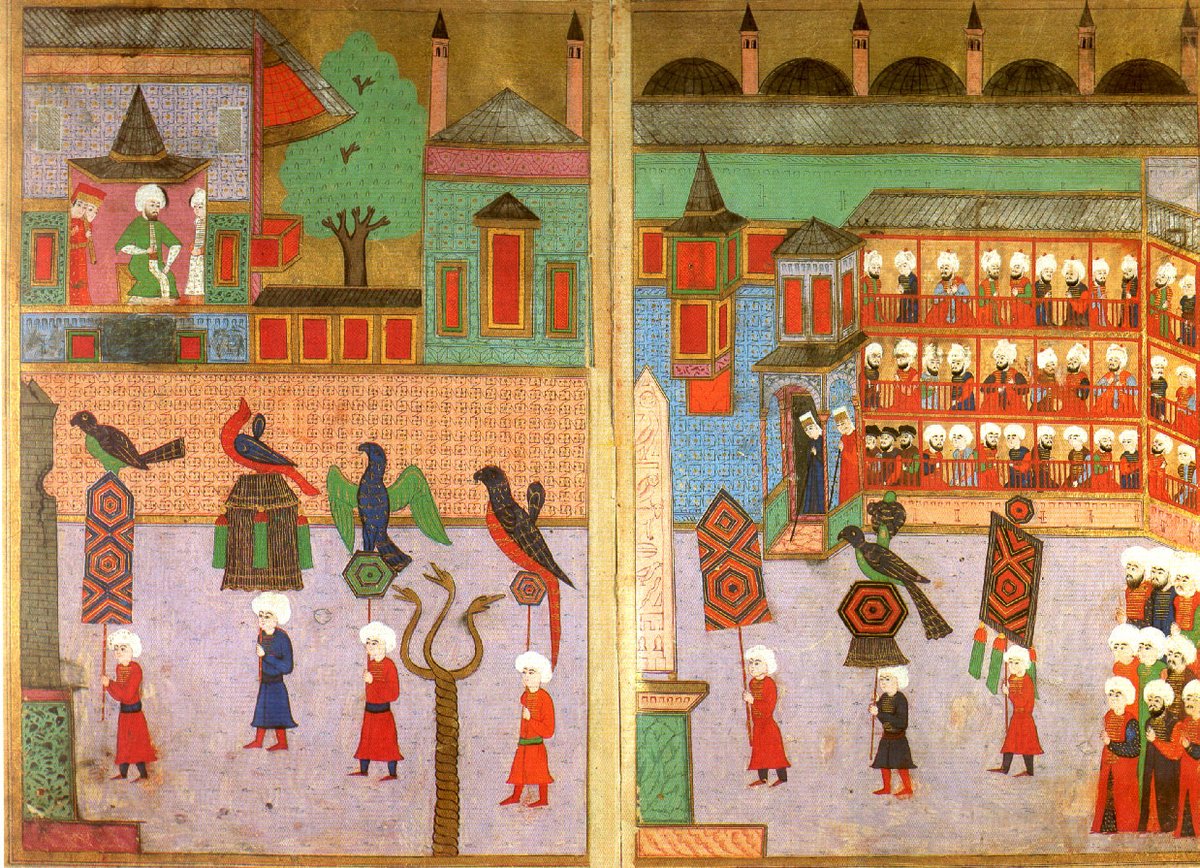

This image of the hippodrome in Istanbul in Ottoman times is just one example. At center, the Serpent Column (from the Greek Temple of Apollo at Delphi) and an Egyptian Obelisk. ‘Imperial Festival Book’ of Intizami (c.1588) Topkapı Palace Library Istanbul, H 1344, fol. 338b–339a.

These objects, which the Ottomans inherited from Byzantine times and carefully preserved, were examples of both & #39;ajab (wonders) and were also thought to have apotropaic or protective properties for the city of Istanbul. They& #39;re still there today.

We might also look at the concept of ‘ibar, the lessons of the past, powerfully evoked by and contained within ruins and ancient sites. The idea that ancient sites and the stories they bear can serve as lessons of history is also found within the Qur’an...

...where in particular, the story of the Pharaoh is presented as a cautionary tale about the perils of overweening vanity and arrogance.

https://art.thewalters.org/detail/84360/joseph-explaining-his-dream-to-the-pharaoh/">https://art.thewalters.org/detail/84...

https://art.thewalters.org/detail/84360/joseph-explaining-his-dream-to-the-pharaoh/">https://art.thewalters.org/detail/84...

Such understandings, of ruins as sites for lessons and reflection, were also filled with longing in pre-Islamic and Islamic poetry:

When you pass by the Pyramids, say:

‘How many are the lessons they have

for the intelligent who would gaze at them!’

- Ahmad ibn Muhammad (d.1482)

When you pass by the Pyramids, say:

‘How many are the lessons they have

for the intelligent who would gaze at them!’

- Ahmad ibn Muhammad (d.1482)

The Caravanserai of Qawsun in Cairo (1341) has a reused threshold slab with hieroglyphics dating to the era of Pharaoh Ramses II (d.1213 BCE) intact and intentionally visible. Centuries later, it& #39;s still there, and the figural imagery has not been altered. Image: Rehab Regaee

Such ancient objects often guarded entrances to mosques, in seeming contradiction to the typical Islamic avoidance of figural imagery in religious spaces, but actually indicating the broad flexibility regarding images that always prevailed in Islam. https://twitter.com/stephenniem/status/927530813989769222?lang=en">https://twitter.com/stephenni...

Why does this matter? These examples of "living with heritage" may differ from what anthropologist Laurajane Smith has called the "Authorized Heritage Discourse" - often embraced by @UNESCO and others. https://twitter.com/cwjones89/status/965936978675019776?s=20">https://twitter.com/cwjones89...

But I would argue that a heritage discourse that is rooted in local ways of valuing and imagining antiquity must be part of any future engagement with ancient sites in the Islamic world.

This is just a little window onto the rich and nuanced complexity of how people in Islamic lands have imagined antiquity over time. If this thread has piqued your curiosity, you can read more here! https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/intellect/ijia/2017/00000006/00000002/art00001;jsessionid=eqaqt5fcdtjo3.x-ic-live-03">https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/i...

Just one mea culpa for this thread! https://twitter.com/tweetistorian/status/1265454768014704640?s=21">https://twitter.com/tweetisto... https://twitter.com/tweetistorian/status/1265454768014704640">https://twitter.com/tweetisto...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter