Structural racism in dermatology: a tweetorial drawn from our pre-published paper:

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/bjd.19217">https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/1... @BrJDermatol #dermtwitter #medthread #tweetorial #MedTwitter

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/bjd.19217">https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/1... @BrJDermatol #dermtwitter #medthread #tweetorial #MedTwitter

Link to paper on Google Drive if you don’t have access: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1AVvU1hgbGowHnOVfjX2XmEt-S7WGowDo/view">https://drive.google.com/file/d/1A...

Thanks to @RoxanaDaneshjou for her excellent take on our paper, I just wanted to add more! https://twitter.com/RoxanaDaneshjou/status/1264291280231620609?s=20">https://twitter.com/RoxanaDan...

First, let me acknowledge that I am white, continue to learn about my own biases, and am constantly striving to do better.

Now to the question - is dermatology possibly racist? Is it structurally racist? How can that be, since dermatologists are excellent doctors who care about the well-being of all their patients? These can all be simultaneously true.

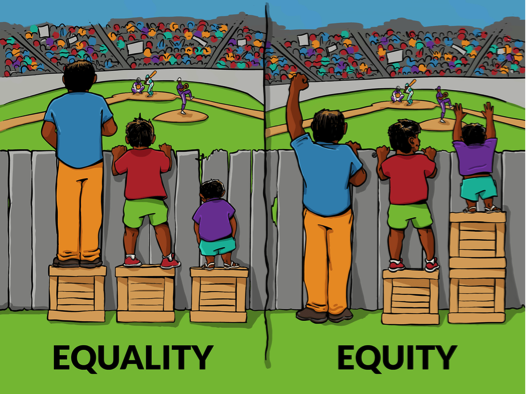

First, let’s talk about what structural racism means, for those of you who might not know the term. Structural racism refers to the historically rooted, multi-modal, culturally reinforcing umbrella that creates and continues to drive inequity based on race.

That means, regardless of anyone’s intent to harm people of certain races, if a system or structure results in people of different races receiving unequal access or benefits, that system is racist (or if you prefer, “structurally racist”).

Many people feel that calling something “racist” means that a person or system must have intentional malignant intent, e.g. using the n-word, or not hiring someone because of their race. But *impact* matters more than *intent*. The road to hell is paved with good intentions, no?

Structural racism has been described in medicine repeatedly, not likely because of anyone’s harmful intent, but by the way the system puts certain people at risk and with fewer resources. @TheLancet https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(17)30569-X/fulltext">https://www.thelancet.com/journals/...

Indeed, in the #COVID19 crisis, the same thing has manifested, putting minorities at greater risk, @JAMA_current: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2766098">https://jamanetwork.com/journals/...

In medicine, we know that there is an implicit “silent curriculum” taught to medical students even that suggests that patients of different races should be treated differently @JAMA_current

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/2293299">https://jamanetwork.com/journals/...

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/2293299">https://jamanetwork.com/journals/...

We’ve also shown how poorly skin of color is represented in dermatology textbooks, unless they are representing infectious disease: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32335181/ ">https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32335181/... @JAADjournals https://drive.google.com/open?id=1hj_lu8ygE18vaaA-hjtN6UAy5VNQPRnB">https://drive.google.com/open...

We all are part of this system and are socialized by it (even people of color), so no need to be defensive – we are all a little bit racist. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RovF1zsDoeM">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

In dermatology, I was struck by how it appears that the ethnicity/race mix of a patient practices, regardless of insurance-type or socioeconomics, could potentially dramatically affect the revenue and profit of a practice.

I’ve often heard conversations about practices improving their “payor mix,” which refers to the mix of insurances a practice takes, and sometimes it’s felt like coded language.

Though all patients have skin problems that can dramatically affect their lives, dermatologists do make more of their money from the procedures that white patients require: biopsies, premalignant destructions (liquid nitrogen cryotherapy), and skin cancer excisions.

So our hypothesis in this paper to explore was, if dermatologists make more money from seeing white patients compared to black patients (in fact, white patients generate three times more insurance expenditures per patient!), then could that exacerbate disparities?

There isn’t that much data out there yet, but we wanted to bring this up, since it is so intuitive that this system of payment (fee-for-service) most likely does exacerbate access and disparities.

Fact is, dermatologists make more money if they see more white people. So why wouldn’t these financial pressures push them, unconsciously and systemically), to see more white people and fewer black people?

This may partly explain what drives practices to be located in communities with more white people and take fewer patients from insurances that pay less (such as Medicaid and Medicare, disproportionately African-American) not to mention these locations are considered desirable.

Also, anecdotally, we have also heard that some practices have been discouraged from expanding access to black patients because it’s not “good business” https://twitter.com/AdeAdamson/status/1087724679446650882?s=20">https://twitter.com/AdeAdamso...

Counterpoint – some might argue that white patients deserve greater access because that’s who has skin cancers. However, I disagree, more skin cancer does not mean white people deserve greater access.

Some may believe that treatment of white patients requires more skill given higher skin cancer burden and thus deserves more pay, or that dermatologic diseases requiring biopsies or procedures are more severe and deserve more attention.

But such thinking can exacerbate a system that may already undervalue African-American patients and the conditions they are more likely to seek dermatologic care for, many manageable without procedures.

The proper dermatologic care of African-American patients (may even require greater cognitive and observational skills, not to mention specialized training during residency.

This includes greater burden of atopic dermatitis, hidradenitis suppurativa, sarcoidosis, and cutaneous lupus. And also, worsened outcomes when these patients get melanoma.

So if the system is racist, what are we to do? First, no one expects that we can fix this overnight. The important things are (1) to be aware of how our system is structurally racist, and (2) actively work to correct it in any way we can.

That means considering how we can improve access to Medicaid and Medicare patients – many doctors don’t cover it, because they pay less. Only 1/3 of dermatologists take Medicaid. https://www.mdedge.com/dermatology/article/136797/practice-management/medicaid-acceptance-33-dermatologists">https://www.mdedge.com/dermatolo...

A quote attributed to Mahatma Gandhi says, “The true measure of any society can be found in how it treats its most vulnerable members.”

If everyone were required to see at least some of these patients, it wouldn’t be that significant a financial burden on those that do.

If everyone were required to see at least some of these patients, it wouldn’t be that significant a financial burden on those that do.

In summary, given our focus on skin, the effects of payment models may be especially patterned by race in dermatology (structurally racist), leading to worsened access for black patients, as well as for disadvantaged patients of all skin types.

Has this been helpful?

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter