If you are looking for a non-Covid (although also grim) read, here is our latest report that aims to document the 1,600+ people who have died in South Texas since 2012 while attempting to enter the United States.

https://www.strausscenter.org/wp-content/uploads/Migrant_Deaths_South_Texas.pdf">https://www.strausscenter.org/wp-conten...

https://www.strausscenter.org/wp-content/uploads/Migrant_Deaths_South_Texas.pdf">https://www.strausscenter.org/wp-conten...

It& #39;s a long report, so here are few highlights:

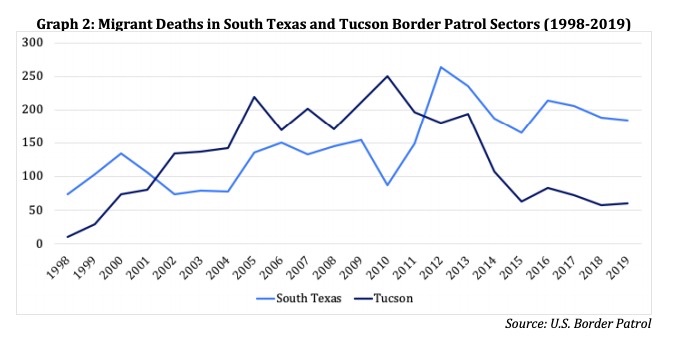

For more than a century, migrants have died in South Texas. Over the years, these numbers have ebbed and flowed in relation to U.S. immigration and labor policy. The takeaway is simple: more legal pathways = fewer deaths.

For more than a century, migrants have died in South Texas. Over the years, these numbers have ebbed and flowed in relation to U.S. immigration and labor policy. The takeaway is simple: more legal pathways = fewer deaths.

Unlike other areas of the U.S.-Mexico border, such as Arizona and California, migrants in South Texas are often moving through private land. This has meant less access for civil society groups, journalists, and researchers.

This can also mean less coverage. Migrant deaths in Arizona have received more attention but since 2012, there have been more migrant deaths in South Texas. In 2019, more than three times more people died in South Texas than in the Arizona desert.

Since 2012, migrants have died in almost every South Texas county. Each county has a unique risk profile depending on its geographic terrain, distance from the border, and nearby Border Patrol checkpoints.

In South Texas, the greatest risks for migrants are crossing the Rio Grande and hiking around Border Patrol checkpoints in arid Texas ranchland. However, individuals are also killed in vehicle accidents, train accidents, and violent crimes.

While Brooks County - with the Falfurrias Border Patrol checkpoint - is notorious for its high number of migrant deaths, since 2018, Webb County (Laredo) has reported the most migrant deaths in South Texas.

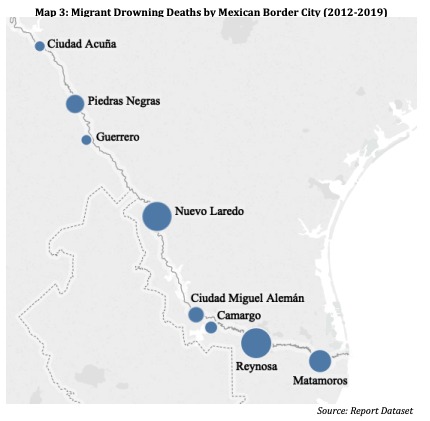

From 2012 to 2019, the report also counted 378 cases where an individual died while attempting to cross the Rio Grande and the body washed up on the Mexican shore. These cases are not counted in Border Patrol statistics or any U.S. database.

This means that some of the most high profile migrant deaths - such as the June 2019 case of the drowned Salvadoran father and daughter in the Rio Grande near Brownsville / Matamoros - are not in any U.S. database.

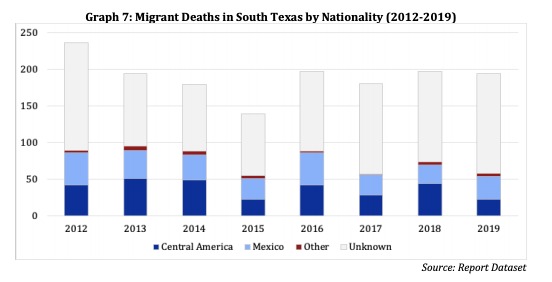

Historically, the majority of individuals dying in South Texas were Mexican. However, since 2012, non-Mexicans have made up more than half of migrant deaths in South Texas each year.

While the stereotypes of migrants crossing between ports of entry focus on men, women made up between 9 and 20 percent of the deaths each year.

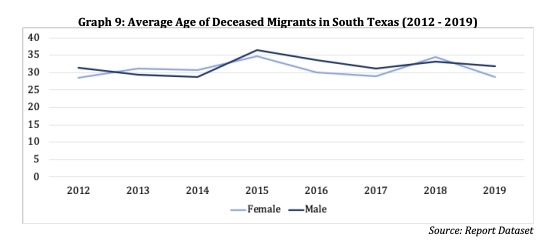

From 2012 to 2019, the average age of deceased individuals in South Texas consistently hovered around 30 years old, with little difference in the average ages of deceased men and women, or among nationalities

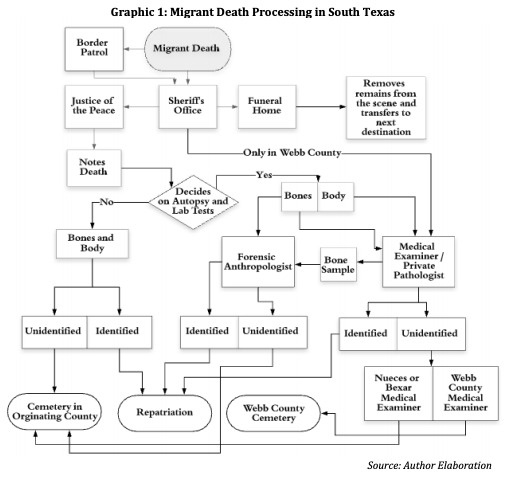

In South Texas, a range of actors process migrant deaths, including federal, state, county, and non-governmental entities. Texas statute guides these processes but there are areas where counties may diverge in their practices.

The report also estimates the cost for counties from each migrant death. It estimates a minimum of $1,100, assuming that there is no autopsy and no cost for a burial plot. When factoring in those and other costs, one migrant death can cost officials up to $13,100.

There is so much more in the report beyond these highlights. This was a 9 month project that brought @SamMichaelLee @victoriaerossi and I to many towns in South Texas. Thanks to everyone who opened their doors to us and answered so many of our questions.

And thanks to the @StraussCenter, the Brumley Fellowship Program, and @BobbyChesney for making it possible!

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter