In the mid-18thC, one of the major worrying diseases was typhus. Nowadays, we know it& #39;s spread by lice or fleas. But at the time, like so many other diseases, it was thought to be caused by noxious air. e.g. malaria literally means "bad air".

Sounds silly? It wasn& #39;t. A thread:

Sounds silly? It wasn& #39;t. A thread:

The idea of noxious miasmas lasted a very long time - well into the late 19th, even early 20th centuries.

And that& #39;s because our ancestors weren& #39;t stupid, even if in hindsight their beliefs seem strange. Their mistaken theory was very much based on empirical observation.

And that& #39;s because our ancestors weren& #39;t stupid, even if in hindsight their beliefs seem strange. Their mistaken theory was very much based on empirical observation.

Typhus, for example, fit the miasma theory especially well because it frequently appeared in confined spaces, like ships& #39; holds, prisons, mines, workhouses, and hospitals. It was often called "gaol fever" or "hospital fever".

And there was the fact that some solutions worked:

And there was the fact that some solutions worked:

Take the ventilator (pictured) - not the kind that is in high demand right now, used to help feed oxygen into a patient& #39;s lungs, but instead a machine used to get air flowing in and out of confined spaces. Think 1740s air-conditioning.

The evidence that it worked was compelling.

The evidence that it worked was compelling.

Given what we know about typhus, removing stale air from a space shouldn& #39;t do anything against it. But mortality noticeably declined wherever it was introduced..

It halved the number of deaths per year in Newgate prison, for example.

It halved the number of deaths per year in Newgate prison, for example.

And on ships, ventilators seemed to reduce mortality among mariners, passengers, soldiers, and especially the group that suffered most from voyages across the 18thC Atlantic: slaves.

But why? After all, ventilators didn& #39;t kill typhus-ridden lice or fleas.

But why? After all, ventilators didn& #39;t kill typhus-ridden lice or fleas.

Perhaps, simply by improving the supply of oxygen to confined spaces, people& #39;s bodies were simply better served to deal with all manner of diseases. Surgeons aboard slave ships sometimes noted that without ventilation, many slaves would simply die in the night of suffocation.

Or perhaps the ventilator& #39;s effectiveness had something to do with its drying effect. It was also used to prevent grain stores becoming humid, thus staving off damp-loving weevils. Typhus-carrying fleas also preferred humid conditions after all.

Regardless, ventilators worked.

Regardless, ventilators worked.

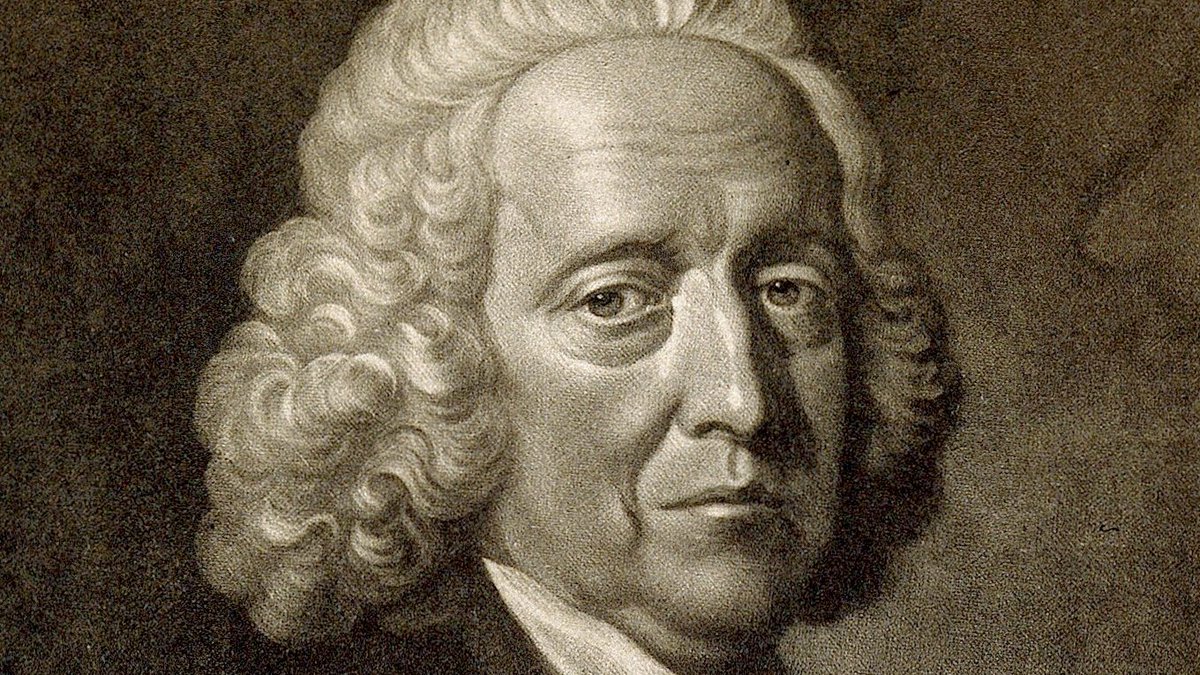

But what& #39;s most interesting about the ventilator is actually its inventor, the Anglican clergyman and scientist Stephen Hales.

He spent most of his career investigating how sap and blood flow through organisms.

But it was not until his 60s that he tried to fight typhus.

He spent most of his career investigating how sap and blood flow through organisms.

But it was not until his 60s that he tried to fight typhus.

Like so many other scientists, he had largely been content to advance our understanding of nature, but not our use of it.

Even his own brother had probably died of typhus, while in prison for debt, but it was decades before Hales applied himself to inventing the ventilator.

Even his own brother had probably died of typhus, while in prison for debt, but it was decades before Hales applied himself to inventing the ventilator.

Once Hales caught the invention bug, however, he could not help but spread it further. He came to believe that more scientists should try to apply their knowledge, for the good of humankind.

He even became something of an evangelists for innovative life hacks.

He even became something of an evangelists for innovative life hacks.

i.e. He advised ladies on how best to prevent limescale in tea kettles, and told them to place a teacup in their pies, upside-down, to prevent the juices boiling over.

But his most lasting legacy was to create an institution that would continue that work.

But his most lasting legacy was to create an institution that would continue that work.

Although Hales was a fellow of the Royal Society, Britain& #39;s premier scientific organisation, he saw the need for an organisation that would systematically promote knowledge& #39;s application.

So, in 1754, in a London coffeehouse called Rawthmell& #39;s, Hales and a few others set it up:

So, in 1754, in a London coffeehouse called Rawthmell& #39;s, Hales and a few others set it up:

They declared themselves the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce.

And 266 years on, it still exists, having done a lot of things to fulfil Hales& #39;s dream - which, sadly, hardly anybody realises.

So I wrote a book about it:

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Arts-Minds-Society-Changed-Nation/dp/0691182647/ref=tmm_hrd_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=&sr=">https://www.amazon.co.uk/Arts-Mind...

And 266 years on, it still exists, having done a lot of things to fulfil Hales& #39;s dream - which, sadly, hardly anybody realises.

So I wrote a book about it:

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Arts-Minds-Society-Changed-Nation/dp/0691182647/ref=tmm_hrd_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=&sr=">https://www.amazon.co.uk/Arts-Mind...

It became Britain& #39;s semi-official national improvement agency, trying to improve anything and everything. So Hales& #39;s love of innovation lived on through it.

For more on Hales and his ventilator (as well as a juicy discount code for the book), see here: https://antonhowes.substack.com/p/age-of-invention-a-breath-of-fresh">https://antonhowes.substack.com/p/age-of-...

For more on Hales and his ventilator (as well as a juicy discount code for the book), see here: https://antonhowes.substack.com/p/age-of-invention-a-breath-of-fresh">https://antonhowes.substack.com/p/age-of-...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter