In this thread, I will discuss a forgotten text "A synopsis of science in Sanskrit and English" by a brilliant Indologist - James Robert Balantyne. I think this text is a critical reading for all enthusiasts who want to develop scientific education in Indian languages.

This is a very interesting book published in 1852, most of which is in Sanskrit! It has a few chapters in English. The English chapters are results from various scientific disciplines, which are then translated into Sanskrit.

Read the book on Google Play: https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=xdgoAAAAYAAJ&hl=en&pg=GBS.PP13">https://play.google.com/books/rea...

Read the book on Google Play: https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=xdgoAAAAYAAJ&hl=en&pg=GBS.PP13">https://play.google.com/books/rea...

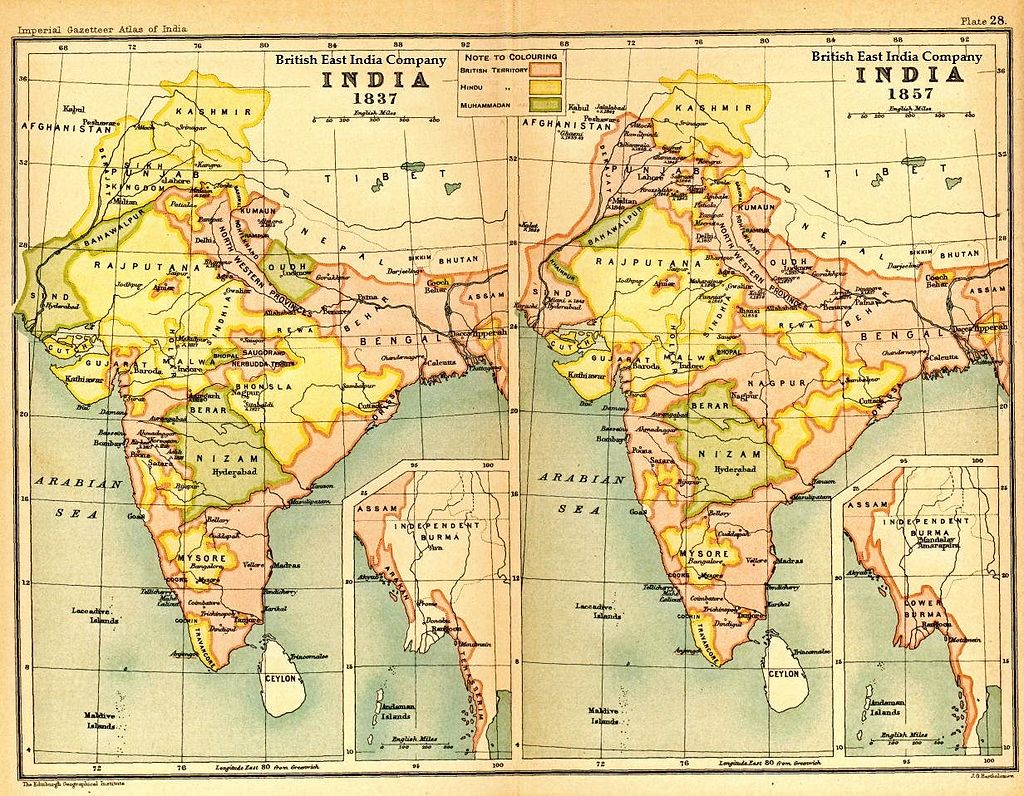

The book was published during the reign of the East India Company (the presidency of Fort William).

The First War of Indian Independence was still about to happen in 1857, ending with the massacre in Delhi.

James R. Ballantyne was a Scottish officer with the East India Company.

The First War of Indian Independence was still about to happen in 1857, ending with the massacre in Delhi.

James R. Ballantyne was a Scottish officer with the East India Company.

The context of the book is the aftermath of the 3rd Anglo-Maratha war which ended in 1818. That was the last serious challenge to colonial rule in India by the Marathas. The British then proceeded to rule India, for which they needed to master the Indian sciences and legal texts.

James R. Ballantyne was building on top of several high officers of East India Company (some of whom even served as its chairmen) who grappled with learning Indian texts in Sanskrit: William Jones, H.T.Colebrooke etc. Ballantyne himself would be later followed by Max Müller.

I find James R. Ballantyne as an extremely important figure for 2 reasons:

1) He translated the texts of Hindu Darśanas (philosophical systems) and provided a critique from the point of view of Christianity.

2) He tried to ground the intellectual debate on scientific knowledge.

1) He translated the texts of Hindu Darśanas (philosophical systems) and provided a critique from the point of view of Christianity.

2) He tried to ground the intellectual debate on scientific knowledge.

The motivation to write "a synopsis of science" in Sanskrit is precisely the intellectual debate for the conversion of India to Christianity. Once the groundwork is laid down, Ballantyne published "Christianity contrasted with Hindu Philosophy", in 1859.

https://ia800904.us.archive.org/6/items/christianitycont00ball/christianitycont00ball.pdf">https://ia800904.us.archive.org/6/items/c...

https://ia800904.us.archive.org/6/items/christianitycont00ball/christianitycont00ball.pdf">https://ia800904.us.archive.org/6/items/c...

It is important to see that until James R. Ballantyne, the intellectual arguments in Europe for the conversion of Hindus were rather lame. These efforts started as early as the Portuguese invasion of India in the 1500s. But the results were shoddy. This would change in the 1800s.

The Hindu Upanishads were translated from Persian by Anquetil Duperron in early 1800s, a French Indologist. The Persian version itself was due to the systematic study of Dara Shikoh.

I see James R. Ballantyne as a worthy successor of Dara Shikoh, and far more talented.

I see James R. Ballantyne as a worthy successor of Dara Shikoh, and far more talented.

Ballantyne did most of his work in Varanasi (Benares) which had been under British rule already from the 1770s. Varanasi is the *the* most important centre of scholarship for the Hindus. As the principal of the Benares Sanskrit College, Ballantyne found very good collaborators.

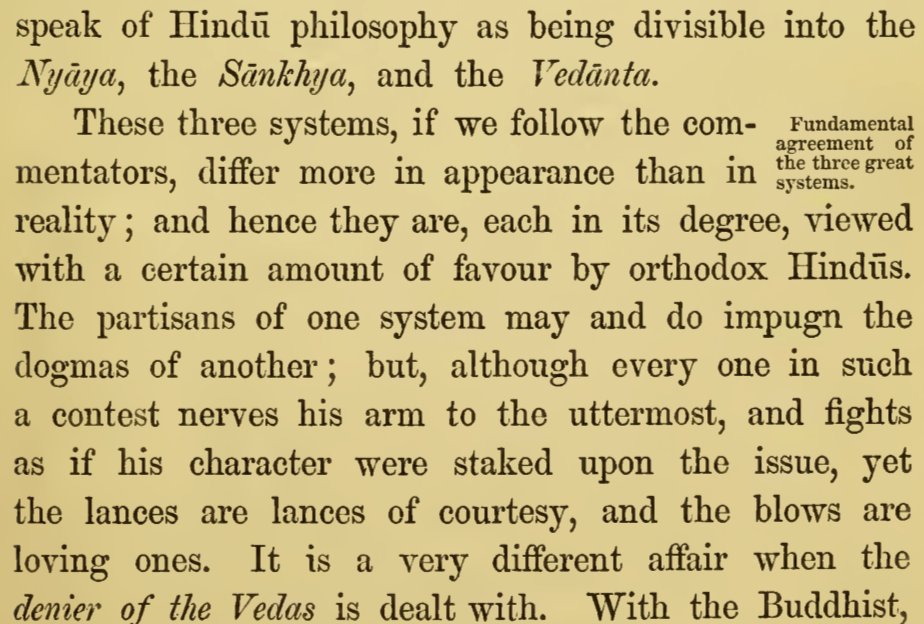

Ballantyne realized that the most serious intellectual opposition for conversion to Christianity came from the Hindu Darśanas, which are 6 in number, grouped in pairs of 3.

1) Nyāya & Vaiśéshika

2) Sāmkhya & Yōga

3) Mīmāmsa & Védānta

He did a "Pūrva Paksha" of the 3 groups.

1) Nyāya & Vaiśéshika

2) Sāmkhya & Yōga

3) Mīmāmsa & Védānta

He did a "Pūrva Paksha" of the 3 groups.

What seemed puzzling to his European colleagues, the 6 Darśanas disagreed and intensely debated with each other !

But Ballantyne realized that these disagreements are like complementary views: how a cylinder would appear as a line, a circle or an ellipse based on how it is cut.

But Ballantyne realized that these disagreements are like complementary views: how a cylinder would appear as a line, a circle or an ellipse based on how it is cut.

Now the genius of Ballantyne is to build an argument for Christianity, based on the internal disagreements of the 3 Indian systems. He specifically narrowed down on the Nyāya system (excellent choice), as a "stone on a sandy beach" that can buttress to "setting up a flag".

He presents this background openly in his preface to the "synopsis of science", unlike the more cunning designs of the later era Indologists.

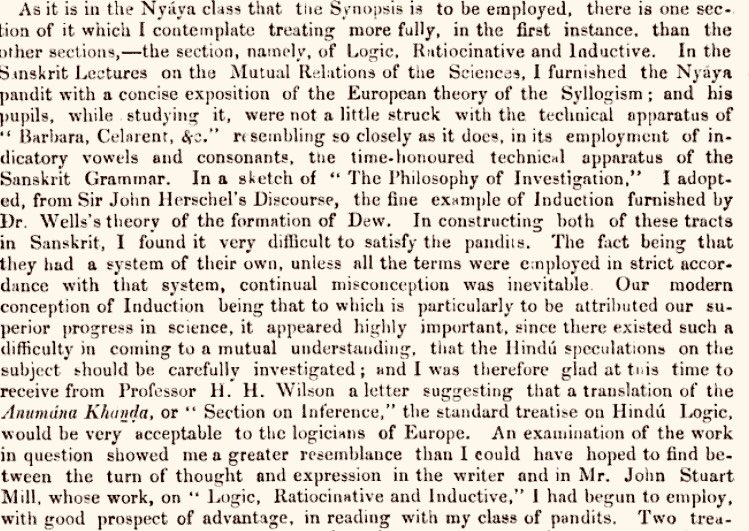

He uses the "Sūtras" (aphorisms) of the Nyāya system as a buttress for scientific knowledge, that ultimately maps to the Christian model.

He uses the "Sūtras" (aphorisms) of the Nyāya system as a buttress for scientific knowledge, that ultimately maps to the Christian model.

The progression of the scientific disciplines Ballantyne chose to translate are Epistemology -> Logic and Grammar -> Mathematics -> Physics -> Chemistry and Biology -> Geography -> Human History, Ethics, Economics and Law. The last would be the foundation for Christian theology.

This is an absolutely brilliant model, stemming all the way from the work of the Catalan philosopher Ramon Llull, who tried to use his "Ars Magna" (encyclopedic knowledge of the world) to convert Muslims (Moors) to Christianity in the 1200s.

Ramon Llull& #39;s "Ars Magna" (Great Work) itself is indebted to the "Zairja" of Arabs, who borrowed a lot from Indian (as well as Chinese and Greek) scientific works. It is remarkable that this reverse mapping into Christianity started as soon as the Iberian peninsula was liberated.

What I find remarkable in Ballantyne& #39;s work is the extremely good selection of scientific results of his time, that he translated into Sanskrit (and into the Nyāya system), before proceeding to make the "Uttara Paksha" (critical response) from the point of view of Christianity.

Why did Ballantyne choose to translate science into Sanskrit, as opposed to Persian, Arabic, Hindustāni or other languages? This is because of the precision and grammatical superiority of Sanskrit (he translated Sanskrit grammar beforehand). The same arguments hold true today.

What I find funny in the above passage is that Ballantyne refuses to comment whether Sanskrit or Arabic is superior, but makes a very snide remark that "one is fit for men and the other is fit for horses".

I am inclined to think that he sees Hindus as "horses".

I am inclined to think that he sees Hindus as "horses".

When Ballantyne was translating science into Sanskrit (1850s), Europe already advanced beyond the know-how of India. Most important Indian scientific results have already been translated, but origin masked. India was worthy of being the horse, about to be reined in by the master.

Now we may wonder if Ballantyne wanted to kickstart a scientific renaissance in Sanskrit (a much needed kick in the butt of the "horse", as Rammohan Roy would& #39;ve phrased it). Nope.

His goal was intellectual sophistry, as revealed by the type of language he chose for translation.

His goal was intellectual sophistry, as revealed by the type of language he chose for translation.

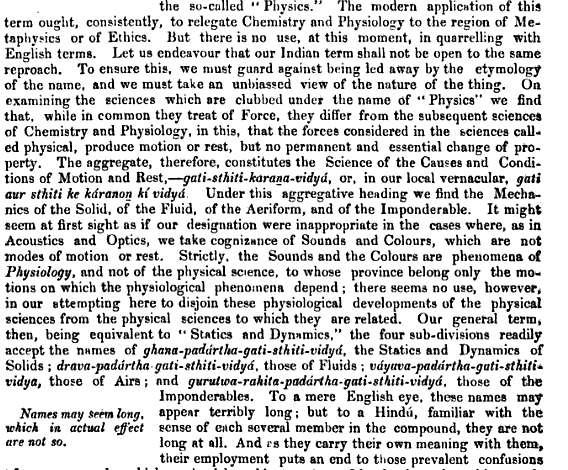

Look at the phenomenally nonsensical translation for the word "physics" that he employed here. Obviously, Sanskrit didn& #39;t value brevity at all, right? LOL. This was the language of Pānini, which he molded into a monstrous useless opponent. This still continues today, by the way.

But despite all this, I consider Ballantyne& #39;s work a very important reading for all Indians. It is telling that in 1850s, it was considered very important to debate in Sanskrit in order to reach the learned scholars of India.

Now of course, everybody in India speaks English.

Now of course, everybody in India speaks English.

The wholesale conversion to English, through secular education made available exclusively in English, was a project already begun by the connivance of Rammohan Roy. It was to be later implemented by the Macaulay reforms. But James R. Ballantyne was a critical piece in the puzzle.

Ballantyne chose the Nyāya system as it is an excellent framework for rational analysis, the foundation for any scientific investigation. However, physical universe is studied separately, in the sister Darśana of Vaiśēshika. In fact, all the 6 Darśanas have scientific components.

Ballantyne was particularly puzzled by the Sāmkhya system, he himself translated the Sāmkhya Sūtras of Kapila. But the evolutionary cosmology of Sāmkhya is so radical and against the Christian model that Ballantyne couldn’t “promote it”.

Please note that Darwin’s work on Natural Selection was still to be published (7 years later in 1859). The Sāmkhya system is a perfect fit for it. There is absolutely no discussion of the most important scientific revolution of the 19th century in the “Synopsis of science”.

However, Ballantyne is guilty of very selective presentation of scientific facts. Even if Darwinian theory was not yet published, there was a fantastic premonition of this in Alexander Humboldt’s work “Kosmos”, which took Europe by storm in the first half of the 19th century.

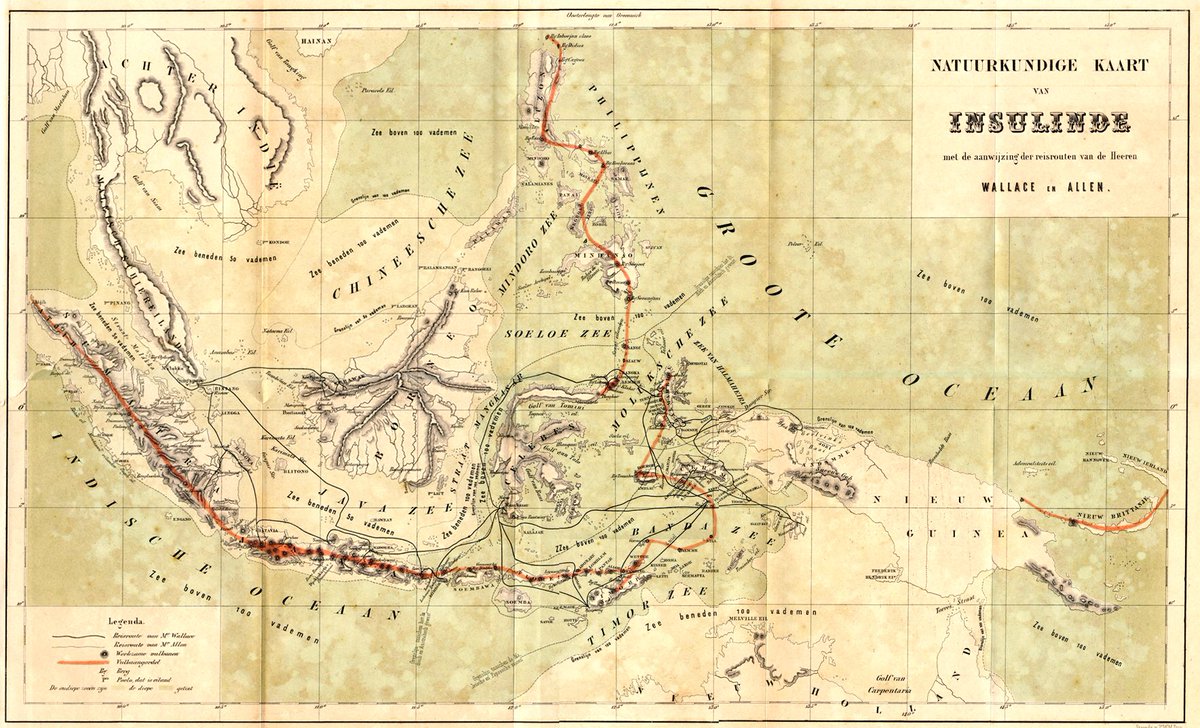

Humboldt was easily the greatest genius in Europe since Leonardo da Vinci. He singlehandedly laid the framework for modern academia, and divorced it from the church. Through direct personal observations, travels and drawings, he spanned scientific work across many disciplines.

“Natural history” as an independent field of study, separate from the Biblical corset of “history” was flowering in Europe. Humboldt’s “cosmos” itself was a tribute to the pagan Greek vision of “harmony between the universe and man”: a very un-Christian model of “destiny of man”.

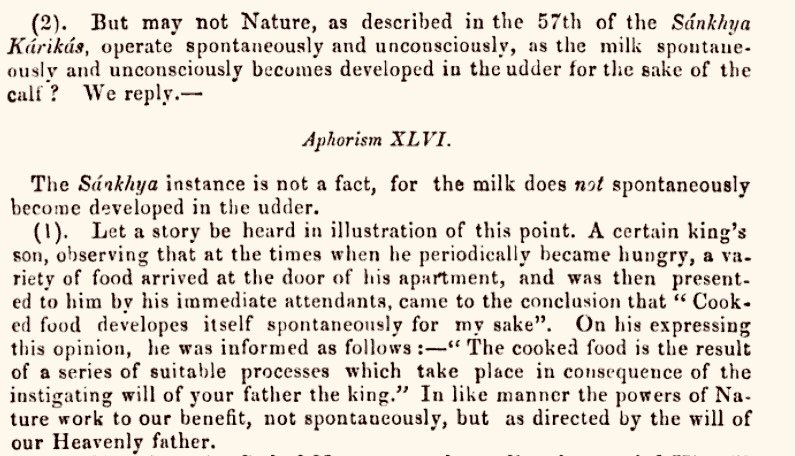

Towards the end of this work (and in his later book), Ballantyne specifically criticizes the Sāmkhya model of “spontaneous order in nature”. He rehashes some European apologetics and some arguments from the internal debates of Hindu Darśanas (without truly understanding them).

It is sad to see that the best opening point of scientific revolution in Indian languages (Ballantyne’s work) was thus constricted into a missionary corset. It doesn’t convey the fever of Humboldt’s “natural philosophy”, that spurred the travels of Darwin and Wallace (pictured).

Ballantyne also floundered in understanding Nyāya syllogisms. Indian logic is not binary, but far more general, with a critique and pessimism with categorical thinking. He noticed the discrepancies but didn’t follow up (or didn’t admit the limitations of European logic openly).

Actually, the more generalized nature of Indian logic is the very reason why the 6 Darśanas exist as independent forms of knowledge enquiry. Ballantyne couldn’t see this, so he based on Nyāya exclusively. I wrote an introductory essay on Indian logic here: http://indiafacts.org/chatuskoti-four-sided-negation/">https://indiafacts.org/chatuskot...

Ballantyne says the Nyāya methods of logical inference (Anumāna) are similar to the work of John Stuart Mill. This smells very fishy and reeking of plans for “digestion” as Rajeev Malhotra put it. Someone needs to go deeper into these works and compare the relative differences.

Rajeev Malhotra has a book “The battle for Sanskrit” where he criticizes the distortions of Indologists, specifically Sheldon Pollock of Colombia University. He contextualized these distortions from the time of Sir William Jones, but he didn’t say a word about Ballantyne.

I think this might be due to lack of time (and space in his book). But he plans to write another book on the historical evolution of Indology. I hope he will give some attention to Ballantyne in this. I am blocked from his account @Rajivmessage. So I cannot tag him.

I find it rather awkward that no Indian scholar seemed to have criticized Ballantyne rigorously. If anybody knows of some references, please point them to me. Dayanand Saraswati, who created the Ārya Samaj completely overlooked Ballantyne in his “Satyārtha Prakāsh”. Puzzling.

Ballantyne used the Nyāya system as something like the equivalent of Aristotle’s syllogisms. By his time, European scholars have systematically exposed the faults of Aristotle (a pagan) and digested him a more extensive Christian model. Ballantyne wanted to do the same to Nyāya.

Actually, Ballantyne had a much worse opinion on the Hindu sciences than he has on Aristotle. He calls them dead of creativity and mindless drudgery. He gives also several examples of questions asked in traditional Hindu exams to prove his point (naturally, with selective bias).

Ballantyne got the work of Francis Bacon translated into Sanskrit by one Vittal Śāstri, to supply what’s missing in Indian sciences: complete lack of application (Bullshit of course). But on this, his opinion was voiced years earlier by Rammohan Roy in his letter to Lord Amherst.

The fact is Nyāya is a very different system to Aristotlean logic. That there could be something in Nyāya (or Sāmkhya) that is missing in European theories is something that Ballantyne never acknowledges.

You wonder why the Pandits were being so nice to him? Strings of money.

You wonder why the Pandits were being so nice to him? Strings of money.

The philosopher Jonardon Ganeri mentioned that Ballantyne was in correspondence with James Mill on Indian logic. Mr. Mill was John Stuart’s dad and wrote an atrocious biased history of India. Those could be the strings of digestion. #v=onepage&q=Jonardon%20Ganeri%20James%20Ballantyne&f=false">https://books.google.de/books?id=8MeoAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA219&dq=Jonardon+Ganeri+James+Ballantyne&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiUxfDO2tTpAhUHBhAIHdwwAGAQ6AEIJTAA #v=onepage&q=Jonardon%20Ganeri%20James%20Ballantyne&f=false">https://books.google.de/books...

Since Ballantyne’s objective was religious conversion of Indians, how does the English language fit in this scheme vs Sanskrit. If only all Indians spoke English, Sanskrit could be discarded. Till then, scholarship in Sanskrit needed to be maintained, with a watchful eye.

At that early period (1850s), the British hold on India was not secure. There was a distinct possibility of India escaping (“the British driven into the sea”). But Ballantyne’s mission was higher: holistic brainwashing of Indians. So Sanskrit needed to be co-opted for this.

Now of course, after 200 odd years of colonized mindsets, English is indelibly etched on the intellectual discourse of India. Sanskrit (or any Indian language) is useless and an annoyance. So the missionary politics in India have moved to promote English medium in Indian schools.

Sanskrit scholarship under the tutelage of East India Company was needed by Ballantyne to make Indians into “staunch allies instead of stubborn opponents” (by that, he probably meant Marathas). He says clearly that this shouldn’t be mistaken for some foolish love with Sanskrit.

Ballantyne started to mold the very vocabulary of Sanskrit and the currency of various words. He enlisted the help of Pandit Bāpū Dēva, and he says these new words made it into the Monier Williams dictionary.

Most of this is harmless, of course. But there could be also mischief.

Most of this is harmless, of course. But there could be also mischief.

Here is Pandit Bāpū Dēva, apparently a great scholar in Indian mathematics and astronomy. But from what I read in the “Synopsis of science”, he seems to be unaware of the work of Mādhava and other Kerala mathematicians.

Ballantyne argued that scientific terminology was needed in Sanskrit, as English terms would steadily degenerate, citing examples of “Butler English”.

“To employ a direct English agency in the tuition of India is entertained by no one.” How much things have changed ! @sankrant

“To employ a direct English agency in the tuition of India is entertained by no one.” How much things have changed ! @sankrant

Ballantyne had to contend with the example of Arabic that borrowed terms from Greek. He says that this was to the detriment of Arabic, as it lost the creative agency with those words.

Ballantyne batted for scientific terms in Sanskrit, against many odds. We must appreciate this.

Ballantyne batted for scientific terms in Sanskrit, against many odds. We must appreciate this.

When we read the above quote carefully, we see that the Sanskrit terms was meant for native Indians alone, who had no facility with English. Ballantyne had no scruples acknowledging that the neologisms in Sanskrit were cumbersome. But he didn’t care! The cumbersomer, the better.

Now I want to comment on the method in which Sanskrit names were chosen for different scientific terms. The easiest to start is with Chemistry, where we have the names for different elements. Ballantyne had to invent names for elements not yet known to India, like “Oxygen” etc.

I find the chosen names not bad. Some of them survived in modern usage of Indian languages. Some like “Prānaprada” for “Oxygen” made way for “Āmlajani” (a literal translation of Greek “acid generator”). So the bad name got stuck in India too.  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😄" title="Smiling face with open mouth and smiling eyes" aria-label="Emoji: Smiling face with open mouth and smiling eyes">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😄" title="Smiling face with open mouth and smiling eyes" aria-label="Emoji: Smiling face with open mouth and smiling eyes">

Ballantyne was clueless about it, but names are not unique in Indian culture. Any object (or person) is considered to exist not independently, but in relationship with other objects. Each relationship provides a different name. So there can be zillions of names for any object.

Proper naming of objects (what the Chinese called “Zhengming”) is the first step for any categorical reasoning. But well, Indian logic has always been pessimistic about categorical reasoning. Ballantyne didn’t understand that point, so he went about naming things rigorously.

I keep wondering how the scientific tradition of taxonomy would have turned out if it kept to the Sanskrit method of allowing multiple names.

Anyways, the taxonomy of Linnaeus was inspired from Sanskrit taxonomy of Hortus Malabaricus, which Ballantyne obviously doesn’t mention.

Anyways, the taxonomy of Linnaeus was inspired from Sanskrit taxonomy of Hortus Malabaricus, which Ballantyne obviously doesn’t mention.

Ballantyne discusses the naming of chemical compounds with a lot of enthusiasm.

Personally, I am disappointed that we have not extended the Sandhi rules of Pānini for chemistry. Sanskrit grammar has a lot more power than simply making agglutinative compound words (like German).

Personally, I am disappointed that we have not extended the Sandhi rules of Pānini for chemistry. Sanskrit grammar has a lot more power than simply making agglutinative compound words (like German).

After Chemistry, there is the task of naming things in Botany/Zoology. Ballantyne made suggestions for families of creatures like “vertebrates”. Unfortunately, this synthesis of names in Sanskrit was not extended to medicine, where India had a highly developed system (Āyurvēda).

Not consulting Āyurvēda and incorporating new scientific knowledge within Āyurvēda was the biggest crime in education during the British Raj. The resulted is a medical education stuck in English for India even today. Amazing that most Indians don’t see the ridiculousness of this.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter