As an art historian and archaeologist, I think about how objects tell stories.

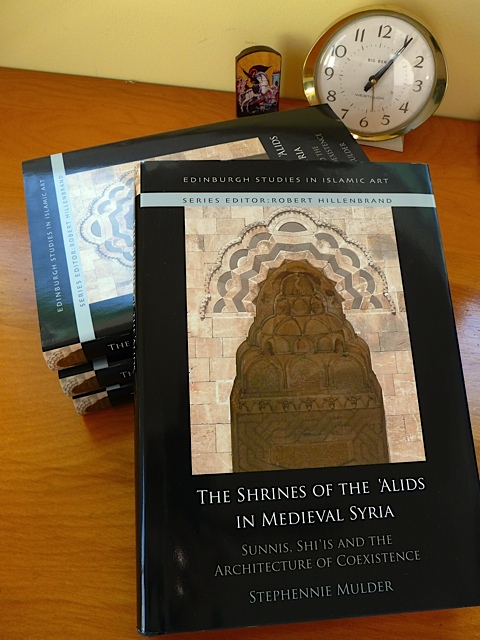

I& #39;d like to lay out a few ideas about method: about what art historians do and how we do it. I& #39;ll use my own book, now in paperback @EdinburghUP! https://edinburghuniversitypress.com/book-the-shrines-of-the-039-alids-in-medieval-syria.html">https://edinburghuniversitypress.com/book-the-...

I& #39;d like to lay out a few ideas about method: about what art historians do and how we do it. I& #39;ll use my own book, now in paperback @EdinburghUP! https://edinburghuniversitypress.com/book-the-shrines-of-the-039-alids-in-medieval-syria.html">https://edinburghuniversitypress.com/book-the-...

Art history is a discipline with a problematic history and as a result, a host of misconceptions. Art history as it& #39;s often taught in secondary and higher ed is still frequently entrenched in Eurocentric paradigms both in terms of subject matter and method.

What does this mean? It means that what& #39;s considered art - and thus worthy of study by art historians - is all-too often still a pretty narrow field, still following definitions laid out in the 17th c. European art academies - the Hierarchy of Genres. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/g/genres">https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-t...

Even in European art, this hierarchy has been challenged for over 140 years - at least since the rise of Impressionism. And yet, astonishingly, many of its underlying assumptions still shape the teaching and popular understanding of what art history is. https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/becoming-modern/avant-garde-france/impressionism/a/a-beginners-guide-to-impressionism">https://www.khanacademy.org/humanitie...

And despite huge strides in the past 30-40 yrs, ARH is still very Euro-American focused. Just open any art history textbook or introductory survey and count the pages devoted to say, ca. 100 years of the Renaissance in the tiny Italian peninsula vs. oh, ALL OF AFRICA FOR ALL TIME

The good news is that though it hasn& #39;t quite found its way into textbooks/popular understanding, art history has transformed radically in the past decades. And I think Islamic art has an extremely important role to play in that - stay tuned for a thread on that later this week!

Amma ba& #39;d (as they say in Arabic) A more productive way to think about what we do in art history is to think about how objects carry stories. The job of an art historian is to use a variety of empirical and theoretical methods to understand how. Al-Shafi& #39;i Mausoleum, Cairo, 1211

For example, there& #39;s a reason the towering 29 m. high medieval dome of Imam al-Shafi& #39;i (pictured above) is only slightly smaller than the Dome of the Rock - even though it was built 500 years later. This building tells a story. I wrote about it here: https://archnet.org/sites/2268/publications/6743">https://archnet.org/sites/226...

But the implicit influence of the European hierarchy of genres means there& #39;s also a reason we tend to think of some objects - say, some oil on a canvas - as more worthy (and worth paying more for) than say, a ceramic bowl. That& #39;s not an accident. https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/4901">https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencolle...

The thing is, most people throughout most of the history of the world didn& #39;t give two figs for some oil on a canvas, or even a fig-less marble sculpture, however glorious or selfie-worthy.

Working & thinking like an anthropologist/archaeologist is helpful in this, because it allows you to escape the straitjacket of "art" and think about "objects." In the 1990s, anthropologist Alfred Gell argued in now-seminal works that objects have agency. https://www.brown.edu/Departments/Joukowsky_Institute/courses/materialworlds/files/1108595.pdf">https://www.brown.edu/Departmen...

For Gell, objects don& #39;t just do the bidding of their makers or patrons, nor do their meanings remain stable over time. They themselves possess the agency of "enchantment": the ability to capture observers& #39; attention, act in the world and change history. The question is, how?

In my book, drawing on the tools of an art historian & an archaeologist, I argue that the shrines of the Prophet Muhammad& #39;s descendants, known as the & #39;Alids, were used in strategies of ecumenism by both Sunni and Shi& #39;i patrons. Shrine of al-Husayn, Aleppo, 1190

This is a somewhat counterintuitive view, since most of the Arabic sources speak of 12th-13th c. as the era of Ihya al-Sunna, or "Sunni Revival", when after more than a century of Shi& #39;i political ascendance, Sunni sovereigns came to power & state-sponsored Sunnism was the norm.

Sunnis and Shi& #39;is are today often presented as being eternal antagonists, but the reality was a lot more complicated. As I& #39;ve argued elsewhere, though there were of course conflicts, most people, most of the time, found ways to get along. https://time.com/5764119/middle-east-war-history/">https://time.com/5764119/m...

The & #39;Alids are often thought of as being more beloved by Shi& #39;is. There& #39;s truth in that. But my research showed that hundreds of shrines to the & #39;Alids were founded in this era, nearly all sponsored by Sunni patrons. What could the explanation be? Cemetery of Bab al-Saghir Damascus

The answer seems to be that though these shrines were particularly beloved by Shi& #39;is, the descendants of the Prophet were of course also revered by Sunnis. That made them ideal as vehicles for rulers who valued stability and whose main priority was not ideological, but pragmatic.

The problem is that shrines are an incredibly dynamic and constantly-changing form of architectural "object". In order to make this argument, I had to draw on a broad range of sources and assess them in the context of the physical evidence of the buildings themselves over time.

The gives us a much broader toolkit: the archaeological and spatial histories of the buildings, the many-layered inscriptions, epigraphy, and iconographical details - like this polyvalent lamp-in-niche motif. Shrine of Husayn, Aleppo, 1198 https://brill.com/view/book/edcoll/9789004280281/B9789004280281-s006.xml">https://brill.com/view/book...

Little of this story could be gleaned from the Arabic textual sources alone - the buildings *are* the technology of enchantment, the carriers of the story. Art historians, then, have all the skills that historians do - we read the sources, we peruse the archives...

But art history gives us this rich reservoir of additional skills - the ability to read, think with, and analyze objects. Gell thought of "art as a system of action, intended to change the world"...

And the shrines of the & #39;Alids aimed to change the medieval sectarian landscape.

Shrine of al-Husayn, Aleppo, 1198, inscription over the portal reading "May God be pleased with all the Companions of His Prophet."

Shrine of al-Husayn, Aleppo, 1198, inscription over the portal reading "May God be pleased with all the Companions of His Prophet."

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter