Dollar Liquidity and International Monetary Notes

Sharing some highlights from this week’s discussion group topic:

We could start the international monetary history clock very far back, but to get up to the contemporary questions quickly /1

Sharing some highlights from this week’s discussion group topic:

We could start the international monetary history clock very far back, but to get up to the contemporary questions quickly /1

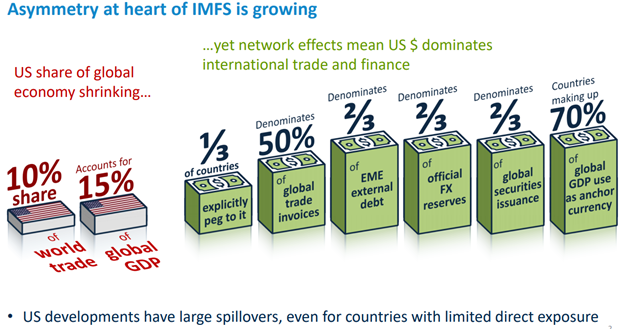

we start with the Dollar System in which there is no official international monetary standard, but the dollar is the de facto standard. The dollar’s role has grown even as the US has shrunk relative to the global economy.

Eichengreen, Hausmann, and Panizza document a phenomenon known in economics as “original sin” which they define as when the domestic currency cannot be used to borrow abroad or possibly even domestically for long horizons.

This amplifies crises bc often crises cause the exchange rate to depreciate, but now its harder to repay the debt, which makes the crisis worse, and so on.

http://www.financialpolicy.org/financedev/hausmann2002.pdf">https://www.financialpolicy.org/financede...

http://www.financialpolicy.org/financedev/hausmann2002.pdf">https://www.financialpolicy.org/financede...

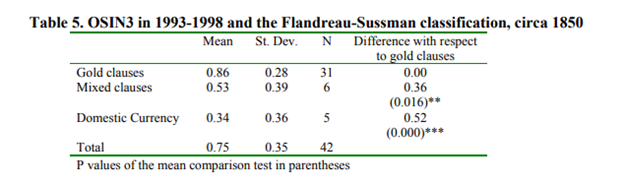

This is actually not specific to the dollar system. Original sin has been persistent for centuries: countries that have a high measure of original sin in the 1990s are correlated with those that had gold tied to issuance in 1850, but uncorrelated w domestic currency issuers then

What drives this? Empirically they surprisingly find that it is not macro policy, inflation, currency depreciation, or institutions. The only correlate they find is country size. Theoretically, there could be a risk premium for foreign investment.

https://bcf.princeton.edu/event-directory/covid19_09/">https://bcf.princeton.edu/event-dir...

https://bcf.princeton.edu/event-directory/covid19_09/">https://bcf.princeton.edu/event-dir...

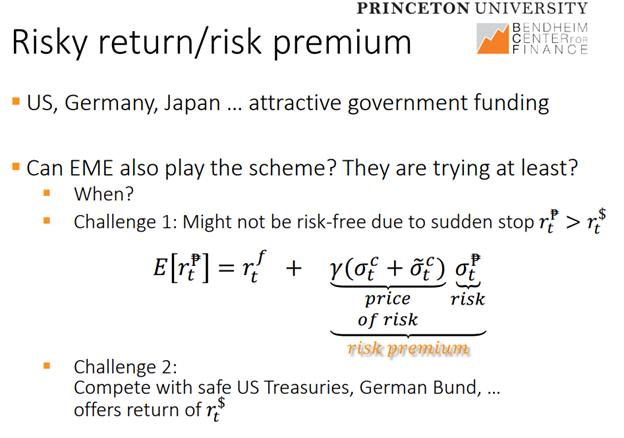

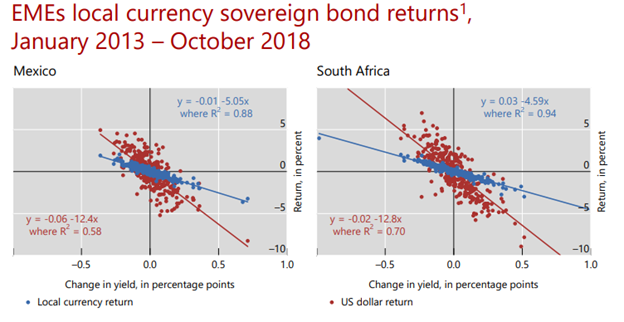

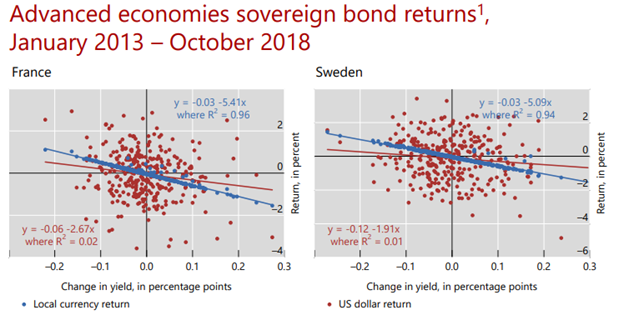

And empirically we see that exchange rates make investor returns more sensitive to changes in domestic interest rates in some countries, but not others. So it makes sense that foreign investors demand a risk premium. Despite these risks dollar borrowing grew.

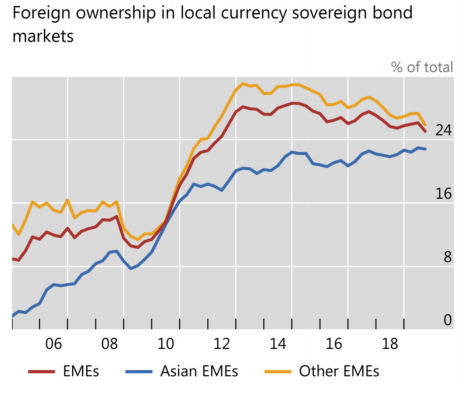

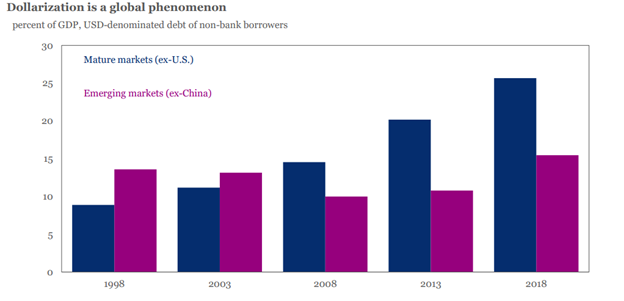

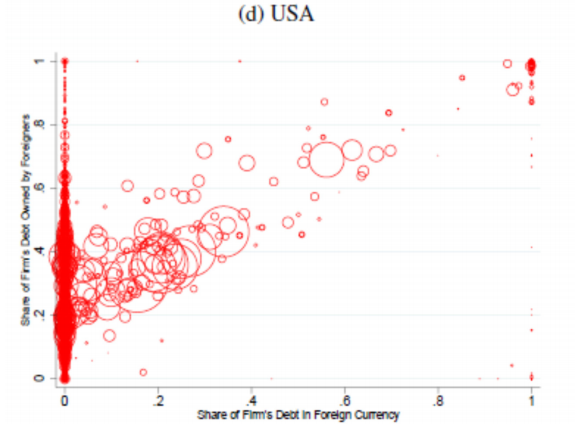

Interestingly EM govs increasingly were able to borrow in local currency, but foreign private sector $ borrowing grew rapidly. When times are good, the foreign risk premium is low & its cheaper to borrow in dollars. This private USD borrowing, Shin calls “Original Sin Redux.”

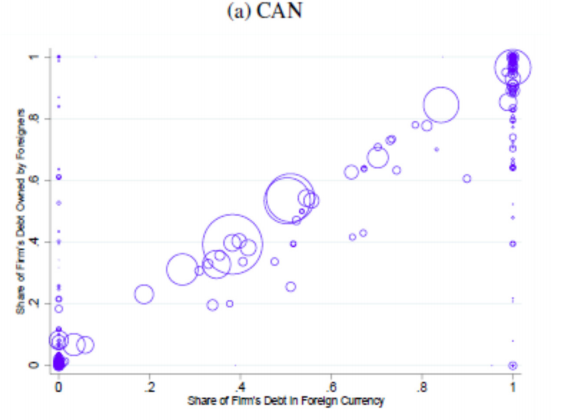

In fact, focusing now more on the private sector, the demand for dollar debt extends well beyond EMs. Even firms in stable, developed countries like Canada have difficulty borrowing from foreigner investors in their local currency, compared with the US.

https://www.nber.org/papers/w24673.pdf">https://www.nber.org/papers/w2...

https://www.nber.org/papers/w24673.pdf">https://www.nber.org/papers/w2...

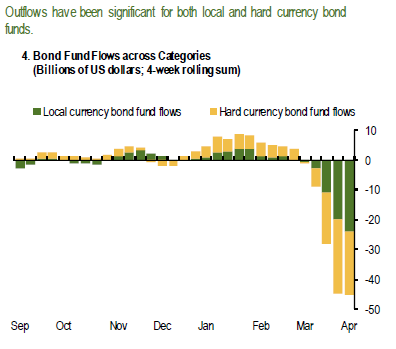

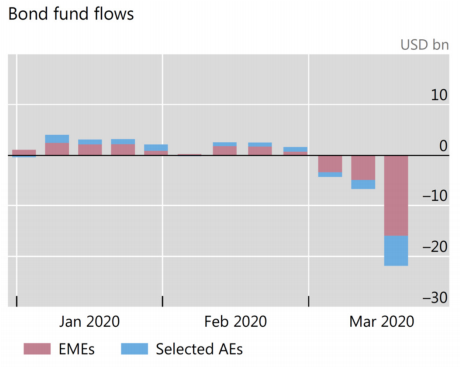

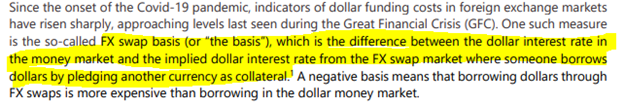

In a crisis the risk premia for foreign investors increases, they withdraw funds & foreign borrowers scramble for US dollars to continue to meet their debt obligations. For example, the FX swap basis widens, which is a measure how hard it is to swap your currency for dollars.

At the same time this tightens financial conditions in the US bc US banks now are facing increased demand both domestically & abroad. This in a sense is like the Triffin dilemma where international capital flows reduce a country’s ability to determine its own monetary conditions.

Countries worried about dollar shortages could discourage foreign inflows in the first place, say taxing foreign lending. More commonly they build large reserves of US dollars to act as a buffer & invest these dollars in US treasury bonds to earn a little interest in the meantime

If they have enough reserves, like China, then there is likely no problem. But this can be costly. For example, foreign countries often have interest rates higher than the US, so FX reserves often exchange a high yielding local currency for a low yielding one, incurring costs.

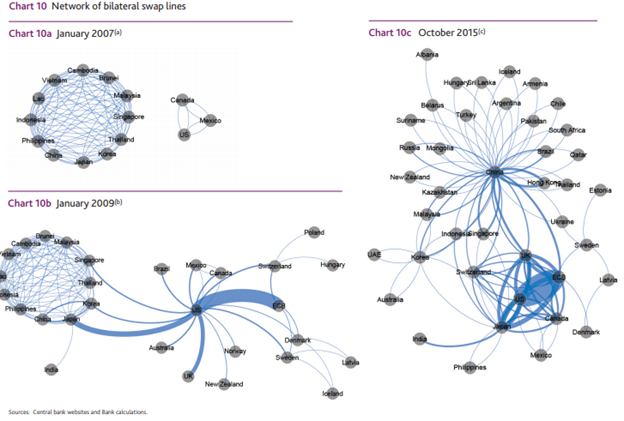

Alternatively, the US can lend dollars to these countries. In the previous crisis they did so using swap lines to several countries, which then also had further swap lines with other countries,

evolving into a patchwork official dollar swap system. @Adam_tooze written wonderfully on the Fed’s tools to address global liquidity, check out his book for more. Here& #39;s a cool BOE chart on swap line evolution:

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/financial-stability-paper/2016/stitching-together-the-global-financial-safety-net.pdf">https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/b...

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/financial-stability-paper/2016/stitching-together-the-global-financial-safety-net.pdf">https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/b...

This crisis the Fed made a new facility that lets countries w treasuries in their FX reserves pledge those for dollars, which can ease the panicked rush for dollar liquidity, but doesnt alleviate the need for large FX reserves before the crisis.

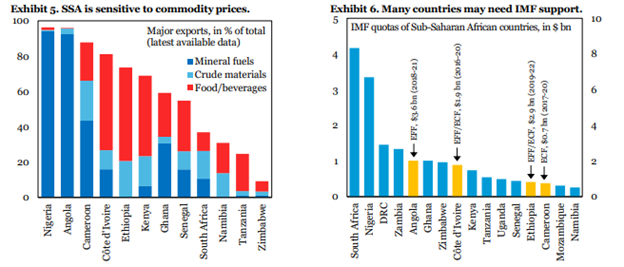

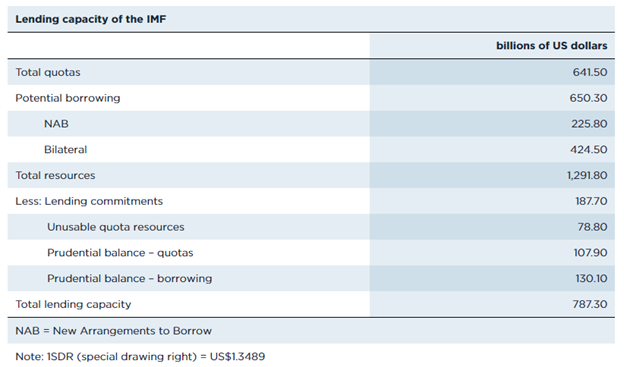

Many countries will still need assistance & there is concern about the ability of institutions such as the IMF to be able to meet the need. @BradSetser & Edwin Truman have provided a wide range of policy suggestions on this front.

https://www.cfr.org/blog/addressing-global-dollar-shortage-more-swap-lines-new-fed-repo-facility-central-banks-more-imf

https://www.cfr.org/blog/addr... href=" https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economic-issues-watch/imf-will-need-more-resources-fight-covid-19-pandemic">https://www.piie.com/blogs/rea...

https://www.cfr.org/blog/addressing-global-dollar-shortage-more-swap-lines-new-fed-repo-facility-central-banks-more-imf

As mentioned, this international role for the dollar raises real questions about whether this system is even really so beneficial to the US. It has been suggested that the dollars’ reserve status provides the US an “exorbitant privilege.” Is that true?

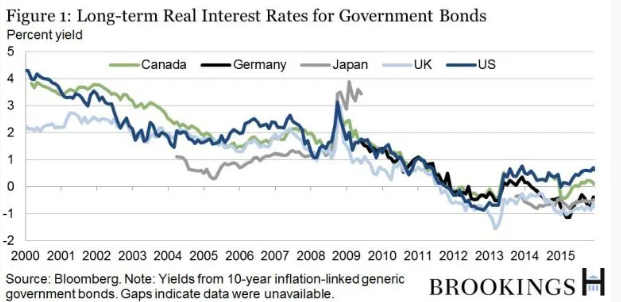

Bernanke argues actually not. US borrowing costs are not generally lower than other advanced countries and the magnitude of seigniorage the US earns from abroad is low. “The exorbitant privilege is not so exorbitant anymore.”

https://www.brookings.edu/blog/ben-bernanke/2016/01/07/the-dollars-international-role-an-exorbitant-privilege-2/">https://www.brookings.edu/blog/ben-...

https://www.brookings.edu/blog/ben-bernanke/2016/01/07/the-dollars-international-role-an-exorbitant-privilege-2/">https://www.brookings.edu/blog/ben-...

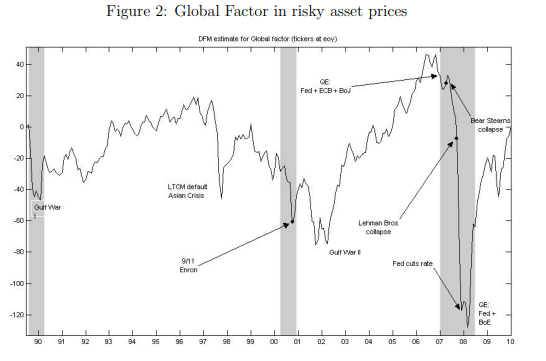

Others argue that there are many privileges of being the reserve currency from less binding financial constraints to not being subject to a global financial cycle driven by US monetary policy since the world borrows in dollars.

https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/pdf/10.1146/annurev-economics-080217-053518

https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/pdf/1... href=" http://www.helenerey.eu/RP.aspx?pid=Published-Papers_en-GB&aid=157224237_67186463733">https://www.helenerey.eu/RP.aspx...

https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/pdf/10.1146/annurev-economics-080217-053518

New research from @i_aldasoro from the BIS shows that there are distinct domestic and global financial cycles, but that the global cycle can amplify domestic ones. https://twitter.com/i_aldasoro/status/1259762575622971392">https://twitter.com/i_aldasor...

Back on the costs of being a reserve currency, @DavidBeckworth points out that this global demand for dollars means that on average the US exchange rate will be higher and interest rates lower, which has distributional consequences by hurting US exports such as manufacturing

and incentivizing excessive borrowing.

A great summary of this point of view on the Odd Lots podcast with @TheStalwart & @tracyalloway https://www.bloomberg.com/news/audio/2019-09-13/why-the-dominant-u-s-dollar-refuses-to-go-away-podcast?sref=LH4eHTC6">https://www.bloomberg.com/news/audi...

A great summary of this point of view on the Odd Lots podcast with @TheStalwart & @tracyalloway https://www.bloomberg.com/news/audio/2019-09-13/why-the-dominant-u-s-dollar-refuses-to-go-away-podcast?sref=LH4eHTC6">https://www.bloomberg.com/news/audi...

So it seems there are both serious benefits & costs to the dollar& #39;s status. The US does not face much the risk the rest of the world faces of suddenly not being able to pay its debts. But it creates new challenges for US monetary policy & potentially distorts the domestic economy

Could we change the current system? What are the options? One is to maintain the current system & accept the “exorbitant responsibility” for providing global dollar liquidity. Perhaps distortionary effects could be mitigated w a more active currency weakening policy from the Fed.

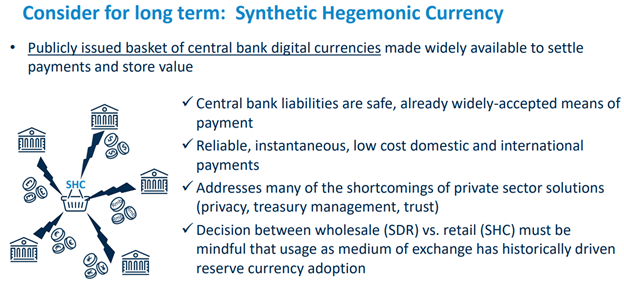

Another option would be to have other currencies as the global standard. People discuss the Euro or Renminbi having this role one day. A creative proposal from Mark Carney is to create a synthetic global hegemonic currency.

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/speech/2019/the-growing-challenges-for-monetary-policy-speech-by-mark-carney.pdf">https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/b...

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/speech/2019/the-growing-challenges-for-monetary-policy-speech-by-mark-carney.pdf">https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/b...

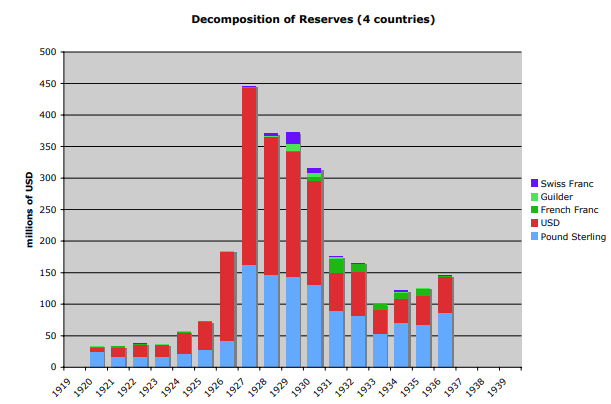

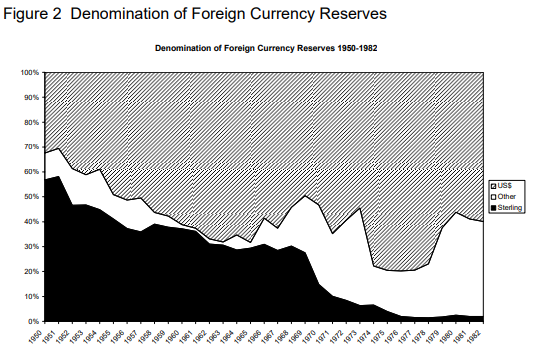

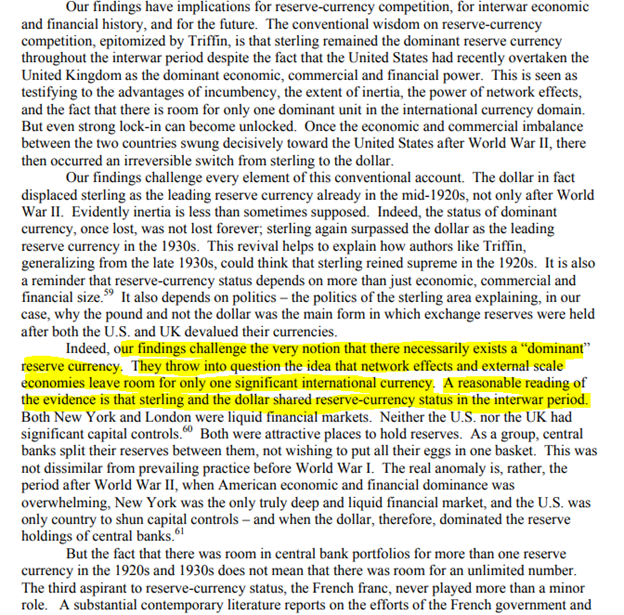

Losing the dollar’s reserve currency status, whether to an international currency or a competitor, is sometimes feared, but historically transitions a have been gradual and the dethroned countries are generally prosperous today.

https://eml.berkeley.edu/~eichengr/rise_fall_dollar_temin.pdf">https://eml.berkeley.edu/~eichengr...

https://eml.berkeley.edu/~eichengr/rise_fall_dollar_temin.pdf">https://eml.berkeley.edu/~eichengr...

Others such as @dandolfa suggest a combination of regulatory and tax incentives to discourage foreign dollar use. https://twitter.com/dandolfa/status/1243288425412919297">https://twitter.com/dandolfa/...

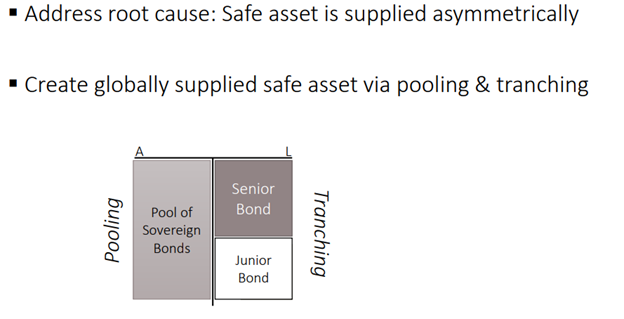

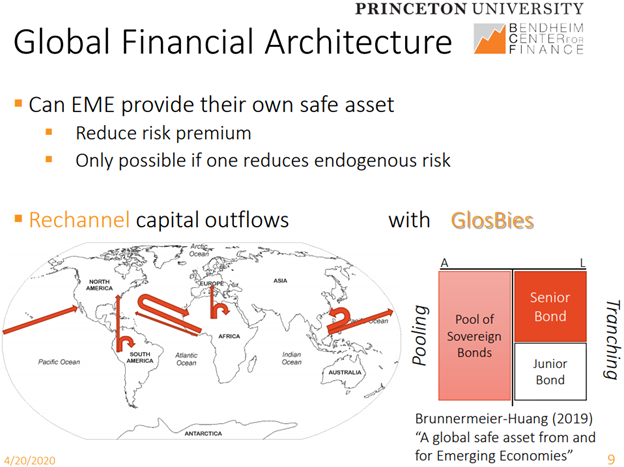

Another proposal, instead of creating a global currency or multicurrency standard, is to create a global safe asset. Brunnermeier for example suggests a collective EM bond with risk tranches.

The idea is that in times of crisis the safer tranches could see inflows even while investors might flee riskier tranches, reducing total EM outflows.

https://scholar.princeton.edu/markus/publications/global-safe-asset-and-emerging-economies">https://scholar.princeton.edu/markus/pu...

https://scholar.princeton.edu/markus/publications/global-safe-asset-and-emerging-economies">https://scholar.princeton.edu/markus/pu...

There are still many questions & issues I didnt cover and/or research has not addressed yet. How can we weigh the benefits & costs to assess the current system? Which policies are best? But maybe this provides a survey & links to further reading for those interested.

One issue I did not write up originally, but upon further thought feel should be added is the legal dimensions of all this. Foreign investors may worry they will not have the same legal protections as locals. This is important bc it helps explain why exchange rate risk may not

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter

https://www.piie.com/blogs/rea..." title="Many countries will still need assistance & there is concern about the ability of institutions such as the IMF to be able to meet the need. @BradSetser & Edwin Truman have provided a wide range of policy suggestions on this front. https://www.cfr.org/blog/addr... href=" https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economic-issues-watch/imf-will-need-more-resources-fight-covid-19-pandemic">https://www.piie.com/blogs/rea...">

https://www.piie.com/blogs/rea..." title="Many countries will still need assistance & there is concern about the ability of institutions such as the IMF to be able to meet the need. @BradSetser & Edwin Truman have provided a wide range of policy suggestions on this front. https://www.cfr.org/blog/addr... href=" https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economic-issues-watch/imf-will-need-more-resources-fight-covid-19-pandemic">https://www.piie.com/blogs/rea...">

https://www.piie.com/blogs/rea..." title="Many countries will still need assistance & there is concern about the ability of institutions such as the IMF to be able to meet the need. @BradSetser & Edwin Truman have provided a wide range of policy suggestions on this front. https://www.cfr.org/blog/addr... href=" https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economic-issues-watch/imf-will-need-more-resources-fight-covid-19-pandemic">https://www.piie.com/blogs/rea...">

https://www.piie.com/blogs/rea..." title="Many countries will still need assistance & there is concern about the ability of institutions such as the IMF to be able to meet the need. @BradSetser & Edwin Truman have provided a wide range of policy suggestions on this front. https://www.cfr.org/blog/addr... href=" https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economic-issues-watch/imf-will-need-more-resources-fight-covid-19-pandemic">https://www.piie.com/blogs/rea...">

https://www.helenerey.eu/RP.aspx..." title="Others argue that there are many privileges of being the reserve currency from less binding financial constraints to not being subject to a global financial cycle driven by US monetary policy since the world borrows in dollars. https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/pdf/1... href=" http://www.helenerey.eu/RP.aspx?pid=Published-Papers_en-GB&aid=157224237_67186463733">https://www.helenerey.eu/RP.aspx..." class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

https://www.helenerey.eu/RP.aspx..." title="Others argue that there are many privileges of being the reserve currency from less binding financial constraints to not being subject to a global financial cycle driven by US monetary policy since the world borrows in dollars. https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/pdf/1... href=" http://www.helenerey.eu/RP.aspx?pid=Published-Papers_en-GB&aid=157224237_67186463733">https://www.helenerey.eu/RP.aspx..." class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>