[THREAD: AKSAI CHIN]

1/50

Napoleon Bonaparte and Czar Alexander met on a raft on the Neman River in July, 1807 to sign the first Treaty of Tilsit. Among the terms was Russia invading Britain in return for French support against the Ottomans.

1/50

Napoleon Bonaparte and Czar Alexander met on a raft on the Neman River in July, 1807 to sign the first Treaty of Tilsit. Among the terms was Russia invading Britain in return for French support against the Ottomans.

2/50

This is what "India" looked like at the time. The British Raj was still half a century away, most of the subcontinent was ruled by a private English corporation (the British East India Company), and Kashmir was largely under the Afghans.

This is what "India" looked like at the time. The British Raj was still half a century away, most of the subcontinent was ruled by a private English corporation (the British East India Company), and Kashmir was largely under the Afghans.

3/50

India was rich. Very, very rich. Naturally, the Brits weren& #39;t keen on losing it and others weren& #39;t keen on letting them keep it. Two big rivals of Lady Britannia at the time were France and Russia. Understandable given their own imperialistic ambitions.

India was rich. Very, very rich. Naturally, the Brits weren& #39;t keen on losing it and others weren& #39;t keen on letting them keep it. Two big rivals of Lady Britannia at the time were France and Russia. Understandable given their own imperialistic ambitions.

4/50

The 1807 treaty seeded what came to be known as the "Tournament of Shadows" to the Russians, the "Great Game" to the rest of the world. A 65-year-long saga of mercurial loyalties, shifting borders, and coercive diplomacy the effects of which are still being felt today.

The 1807 treaty seeded what came to be known as the "Tournament of Shadows" to the Russians, the "Great Game" to the rest of the world. A 65-year-long saga of mercurial loyalties, shifting borders, and coercive diplomacy the effects of which are still being felt today.

5/50

The Game itself would begin only in 1830. That& #39;s over 8 years since Napoleon died of stomach cancer on Saint Helena and about 5 since the Czar died of typhus in a remote village by the Black Sea. Because what didn& #39;t die with the 2 imperialists was their imperialism.

The Game itself would begin only in 1830. That& #39;s over 8 years since Napoleon died of stomach cancer on Saint Helena and about 5 since the Czar died of typhus in a remote village by the Black Sea. Because what didn& #39;t die with the 2 imperialists was their imperialism.

6/50

What Britain needed most desperately was a buffer between its "crown jewel" and an ever-ambitious Russia. What Russia needed most desperately was a buffer between its Central Asian interests and those of Britain. This is where Russia& #39;s interest in Afghanistan took shape.

What Britain needed most desperately was a buffer between its "crown jewel" and an ever-ambitious Russia. What Russia needed most desperately was a buffer between its Central Asian interests and those of Britain. This is where Russia& #39;s interest in Afghanistan took shape.

7/50

William Bentinck, Governor General of EIC& #39;s India, sought to establish "business relations" with the Emirates of Bukhara and Afghanistan and eventually expand influence over the Ottoman Empire and Persia. This would offer it a buffer against any Russian misadventure.

William Bentinck, Governor General of EIC& #39;s India, sought to establish "business relations" with the Emirates of Bukhara and Afghanistan and eventually expand influence over the Ottoman Empire and Persia. This would offer it a buffer against any Russian misadventure.

8/50

Now the Afghans had their own ongoing friction with the Sikhs to deal with, especially after having lost Peshawar to the latter in a recent battle. The Brits, thus, could not be in alliance with both parties at once. They had to pick one. This wasn& #39;t difficult.

Now the Afghans had their own ongoing friction with the Sikhs to deal with, especially after having lost Peshawar to the latter in a recent battle. The Brits, thus, could not be in alliance with both parties at once. They had to pick one. This wasn& #39;t difficult.

9/50

The Sikhs had a formidable army trained and armed by the French. The Afghans didn& #39;t have an army to begin with, much less a trained one. Sure they had a tiny levy of tribal "jihadists" willing to die for the Emir, but that was no match for the enormity of Dal Khalsa.

The Sikhs had a formidable army trained and armed by the French. The Afghans didn& #39;t have an army to begin with, much less a trained one. Sure they had a tiny levy of tribal "jihadists" willing to die for the Emir, but that was no match for the enormity of Dal Khalsa.

10/50

The choice, however, got complicated when Russia sent an envoy to Kabul in an attempt to win over the Emir, Dost Mohammad Khan. Much mutual suspicion ensued and Britain invaded Afghanistan in the First Anglo-Afghan War of 1838. And lost badly.

The choice, however, got complicated when Russia sent an envoy to Kabul in an attempt to win over the Emir, Dost Mohammad Khan. Much mutual suspicion ensued and Britain invaded Afghanistan in the First Anglo-Afghan War of 1838. And lost badly.

11/50

One year into the Anglo-Afghan War, Maharaja Ranjit Singh was dead, but not before having successfully annexing Kashmir and Ladakh into his Empire. With Maharaja& #39;s death, the Empire began to fall apart with 2 of his inheritors dying in quick succession.

One year into the Anglo-Afghan War, Maharaja Ranjit Singh was dead, but not before having successfully annexing Kashmir and Ladakh into his Empire. With Maharaja& #39;s death, the Empire began to fall apart with 2 of his inheritors dying in quick succession.

12/50

The power struggle that followed between the Sikhs and the Dogras only weakened the Empire further and set off the First Anglo-Sikh War of 1845. The following year on March 9, the Treaty of Lahore was signed signaling the end of the conflict. In Britain& #39;s favor.

The power struggle that followed between the Sikhs and the Dogras only weakened the Empire further and set off the First Anglo-Sikh War of 1845. The following year on March 9, the Treaty of Lahore was signed signaling the end of the conflict. In Britain& #39;s favor.

13/50

Among the terms of this treaty was the surrender of Kashmir to the Company as war reparations. Later, in a separate arrangement, the territory was purchased for ₹7.5 million by Gulab Singh, the Dogra king of Jammu. This is where J&K takes shape as a package entity.

Among the terms of this treaty was the surrender of Kashmir to the Company as war reparations. Later, in a separate arrangement, the territory was purchased for ₹7.5 million by Gulab Singh, the Dogra king of Jammu. This is where J&K takes shape as a package entity.

14/50

By this point, Britain has secured a major victory, and a trade deal as a result, with China in what came to be known as the Opium War of 1840. Until that point, China had mostly been closed to foreign business. This victory practically pried it open.

By this point, Britain has secured a major victory, and a trade deal as a result, with China in what came to be known as the Opium War of 1840. Until that point, China had mostly been closed to foreign business. This victory practically pried it open.

15/50

Those days, Tibet was an independent entity with no beef with anyone outside of its borders. The Chinese wouldn& #39;t seriously bother it until at least a hundred years later. But that doesn& #39;t mean others didn& #39;t. Remember Ranjit Singh? He had sons. One of them was Sher Singh.

Those days, Tibet was an independent entity with no beef with anyone outside of its borders. The Chinese wouldn& #39;t seriously bother it until at least a hundred years later. But that doesn& #39;t mean others didn& #39;t. Remember Ranjit Singh? He had sons. One of them was Sher Singh.

16/50

Immediately upon coronation in 1941, driven by a strange whim, Sher Singh decided to invade Tibet. Not a wise move because, a) Tibet is no Punjab, and b) Sher Singh was not his father. He ended up losing not only his Tibet misadventure but also Leh.

Immediately upon coronation in 1941, driven by a strange whim, Sher Singh decided to invade Tibet. Not a wise move because, a) Tibet is no Punjab, and b) Sher Singh was not his father. He ended up losing not only his Tibet misadventure but also Leh.

17/50

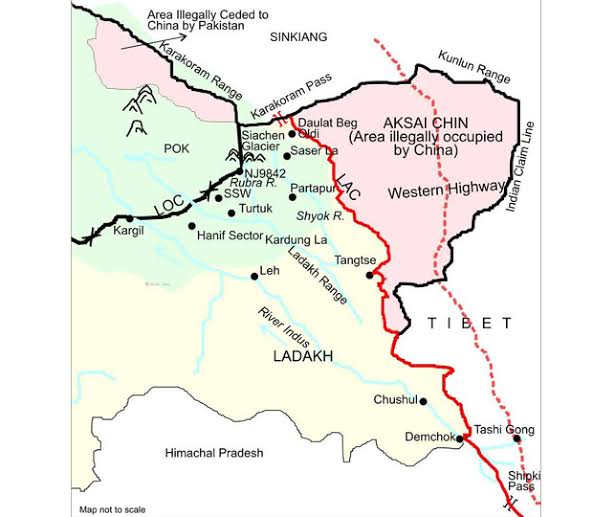

The 1846 Treaty of Lahore that cost the Sikhs Kashmir, had also cost them Ladakh. Now Ladakh and China do share a border, but the line wasn& #39;t exactly drawn. And given the region& #39;s general sterility, neither the Brits nor the Chinese bothered either.

The 1846 Treaty of Lahore that cost the Sikhs Kashmir, had also cost them Ladakh. Now Ladakh and China do share a border, but the line wasn& #39;t exactly drawn. And given the region& #39;s general sterility, neither the Brits nor the Chinese bothered either.

18/50

But if you don& #39;t define a border, things can go wrong. And what can go wrong, mostly will. The border started at Pangong Tso in the south and ended at the Karakoram Pass in the north. Its trajectory though, that& #39;s what nobody bothered defining. At least not right away.

But if you don& #39;t define a border, things can go wrong. And what can go wrong, mostly will. The border started at Pangong Tso in the south and ended at the Karakoram Pass in the north. Its trajectory though, that& #39;s what nobody bothered defining. At least not right away.

19/50

Between the two points, Pangong Lake and Karakoram Pass, lies one of the most unforgiving pieces of real estate on the planet. So barren, even grass is a novelty there. It& #39;s over 9 million acres of death and desolation. It& #39;s Aksai Chin.

Between the two points, Pangong Lake and Karakoram Pass, lies one of the most unforgiving pieces of real estate on the planet. So barren, even grass is a novelty there. It& #39;s over 9 million acres of death and desolation. It& #39;s Aksai Chin.

20/50

Major General Sir Andrew Scott Waugh was a Surveyor General of India and is credited to have named Mt. Everest after his boss. As the first human to have surveyed the Himalayas in detail, Waugh had earned quite the repute for his skills. Training under him was a privilege.

Major General Sir Andrew Scott Waugh was a Surveyor General of India and is credited to have named Mt. Everest after his boss. As the first human to have surveyed the Himalayas in detail, Waugh had earned quite the repute for his skills. Training under him was a privilege.

22/50

One individual to have enjoyed that privilege was a British surveyor by the name William H. Johnson. Ladakh at the time was being governed by a Mehta Mangal for Raja Gulab Singh under British suzerainty. In 1855, Mehta Mangal commissioned Johnson to survey Kashmir.

One individual to have enjoyed that privilege was a British surveyor by the name William H. Johnson. Ladakh at the time was being governed by a Mehta Mangal for Raja Gulab Singh under British suzerainty. In 1855, Mehta Mangal commissioned Johnson to survey Kashmir.

23/50

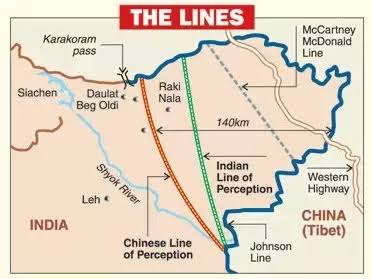

This was the first serious attempt at drawing lines on one of the world& #39;s most daunting terrains. By 1865, Johnson was working out of Ladakh, defining the territory& #39;s eastern frontier. The job was completed the same year and the border came to be known as the Johnson Line.

This was the first serious attempt at drawing lines on one of the world& #39;s most daunting terrains. By 1865, Johnson was working out of Ladakh, defining the territory& #39;s eastern frontier. The job was completed the same year and the border came to be known as the Johnson Line.

24/50

Johnson Line was the first official border in the region and it placed Aksai Chin firmly within the Indian territory. Only one problem though — it wasn& #39;t presented to China. China at the time was battling a bitter Dungan revolt and Gulab Singh decided to leave it alone.

Johnson Line was the first official border in the region and it placed Aksai Chin firmly within the Indian territory. Only one problem though — it wasn& #39;t presented to China. China at the time was battling a bitter Dungan revolt and Gulab Singh decided to leave it alone.

25/50

That was fine then, but it left the legitimacy of the newly-drawn border open to scrutiny. Understandable given a border is only valid when parties on either side of the line concur. Here, one party wasn& #39;t even aware of such a line!

That was fine then, but it left the legitimacy of the newly-drawn border open to scrutiny. Understandable given a border is only valid when parties on either side of the line concur. Here, one party wasn& #39;t even aware of such a line!

26/50

China finally managed to crush the Dungan revolt in 1877 and the Qing rule was restored over the region. This is when it turned eyes on Xinjiang in general and Aksai Chin in particular. By 1893, Hung Ta-chen, a Chinese official, had completed his own survey of the region.

China finally managed to crush the Dungan revolt in 1877 and the Qing rule was restored over the region. This is when it turned eyes on Xinjiang in general and Aksai Chin in particular. By 1893, Hung Ta-chen, a Chinese official, had completed his own survey of the region.

27/50

Hung& #39;s survey placed Aksai Chin within Xinjiang, ergo China. Naturally, China adopted this as its official version. This was also presented to the British consul general George McCartney at Kashgar who promptly approved and forwarded it further up the hierarchy.

Hung& #39;s survey placed Aksai Chin within Xinjiang, ergo China. Naturally, China adopted this as its official version. This was also presented to the British consul general George McCartney at Kashgar who promptly approved and forwarded it further up the hierarchy.

28/50

At the time, Colonel Sir Claude Maxwell MacDonald was Her Magesty& #39;s Minister in China. One of MacDonald& #39;s legacies is the Hong Kong problem. He& #39;s credited to have secured the Second Peking Convention in which China leased HK to Britain for 99 years.

At the time, Colonel Sir Claude Maxwell MacDonald was Her Magesty& #39;s Minister in China. One of MacDonald& #39;s legacies is the Hong Kong problem. He& #39;s credited to have secured the Second Peking Convention in which China leased HK to Britain for 99 years.

29/50

This was problematic only because he thought 99 years was as good as forever. Also because Kowloon which lies well inside HK came on a lease-in-perpetuity. See why this should create problems 99 years down the line? Anyway, I digress.

This was problematic only because he thought 99 years was as good as forever. Also because Kowloon which lies well inside HK came on a lease-in-perpetuity. See why this should create problems 99 years down the line? Anyway, I digress.

30/50

So MacDonald liked the proposal sent to him by George McCartney and responded with a note in 1899 calling Hung& #39;s survey the Macartney-MacDonald Line. As the first real border kind of agreed upon by both parties, this line holds special significance. Why kind of? We& #39;ll see.

So MacDonald liked the proposal sent to him by George McCartney and responded with a note in 1899 calling Hung& #39;s survey the Macartney-MacDonald Line. As the first real border kind of agreed upon by both parties, this line holds special significance. Why kind of? We& #39;ll see.

31/50

So this far, we& #39;ve seen 2 lines — the Johnson Line which puts Aksai Chin in India and its accepted by the British but not the Chinese, and the Macartney-MacDonald Line which puts Aksai Chin in China but is accepted by both China and Britain.

So this far, we& #39;ve seen 2 lines — the Johnson Line which puts Aksai Chin in India and its accepted by the British but not the Chinese, and the Macartney-MacDonald Line which puts Aksai Chin in China but is accepted by both China and Britain.

32/50

There& #39;s a reason Britain so readily agreed to the survey. It ties in with the Great Game. Here& #39;s how: Part of this line follows the Laktsang Range. To the north of this range is Aksai Chin proper; to the south, the Lingzi Tang plains. This trade-off worked for Britain.

There& #39;s a reason Britain so readily agreed to the survey. It ties in with the Great Game. Here& #39;s how: Part of this line follows the Laktsang Range. To the north of this range is Aksai Chin proper; to the south, the Lingzi Tang plains. This trade-off worked for Britain.

33/50

By ceding parts of Aksai Chin to China, Britain not only secured a formidable northern boundary in the Karakoram, but also created a secondary buffer against the Russians in the form of a Chinese-controlled Aksai Chin proper and Tarim Basin. The plan was a winner.

By ceding parts of Aksai Chin to China, Britain not only secured a formidable northern boundary in the Karakoram, but also created a secondary buffer against the Russians in the form of a Chinese-controlled Aksai Chin proper and Tarim Basin. The plan was a winner.

34/50

But here& #39;s something funny, the Qing government never officially responded to MacDonald& #39;s note. Some say the Chinese assent was implicit given the original survey itself was conducted and proposed by Hung, a Chinese official. Whatever be the case, this complicated matters.

But here& #39;s something funny, the Qing government never officially responded to MacDonald& #39;s note. Some say the Chinese assent was implicit given the original survey itself was conducted and proposed by Hung, a Chinese official. Whatever be the case, this complicated matters.

35/50

It& #39;s also said that the original survey by Hung Ta-chen placed the entirety of Aksai Chin within British Indian territory but was later modified by MacDonald to place parts thereof in China. Anyway, since China didn& #39;t officially respond to this note, things remained fuzzy.

It& #39;s also said that the original survey by Hung Ta-chen placed the entirety of Aksai Chin within British Indian territory but was later modified by MacDonald to place parts thereof in China. Anyway, since China didn& #39;t officially respond to this note, things remained fuzzy.

36/50

In a major development in 1911, the Qing regime was overthrown in a mass uprising and China became a republic. It& #39;s called the Xinhai Revolution. 3 years later, Europe went to war. By the time WW1 ended, Russia had abandoned monarchy too. Much stood changed now.

In a major development in 1911, the Qing regime was overthrown in a mass uprising and China became a republic. It& #39;s called the Xinhai Revolution. 3 years later, Europe went to war. By the time WW1 ended, Russia had abandoned monarchy too. Much stood changed now.

37/50

Now that both China and Russia were republics, the Great Game was no longer a necessity. Also note that Russia, Britain, and France were allies in the Great War, so many equations were changing and standing rapidly. The ownership of Aksai Chin, however, remained unclear.

Now that both China and Russia were republics, the Great Game was no longer a necessity. Also note that Russia, Britain, and France were allies in the Great War, so many equations were changing and standing rapidly. The ownership of Aksai Chin, however, remained unclear.

38/50

Things were so fluid at the time, says Neville Maxwell, the British used no fewer than 11 different lines depending on political imperatives of the moment. From the end of WW1 through the beginning of WW2, the Postal Atlas of China followed the Johnson Line.

Things were so fluid at the time, says Neville Maxwell, the British used no fewer than 11 different lines depending on political imperatives of the moment. From the end of WW1 through the beginning of WW2, the Postal Atlas of China followed the Johnson Line.

39/50

The Peking University Atlas of 1925 also placed Aksai Chin in India. In fact, this one drew the border along the Kunlun Range which gave Kashmir not only Aksai Chin but also parts of the Xinjiang Autonomous Region. Through all these events, Aksai Chin remained uninhabited.

The Peking University Atlas of 1925 also placed Aksai Chin in India. In fact, this one drew the border along the Kunlun Range which gave Kashmir not only Aksai Chin but also parts of the Xinjiang Autonomous Region. Through all these events, Aksai Chin remained uninhabited.

40/50

The British reasserted their primacy of Johnson Line in 1940-41 after they learnt of Soviet officials surveying Aksai Chin for the Xinjiang warlord. Although Russia and Britain were now allies, they still viewed each other with a decent amount of suspicion.

The British reasserted their primacy of Johnson Line in 1940-41 after they learnt of Soviet officials surveying Aksai Chin for the Xinjiang warlord. Although Russia and Britain were now allies, they still viewed each other with a decent amount of suspicion.

41/50

Despite all of this though, Britain never really bothered to do anything meaningful about its claim on the region. At least not outside of the map. India won independence in 1947 without a single military outpost or human settlement in the barn wasteland.

Despite all of this though, Britain never really bothered to do anything meaningful about its claim on the region. At least not outside of the map. India won independence in 1947 without a single military outpost or human settlement in the barn wasteland.

42/50

The newly-liberated nation picked the Ardagh-Johnson Line (a slightly modified version of Johnson Line) as its official Sino-Ladakh border placing a firm claim on Aksai Chin but not on the sliver of Xinjiang granted by the Peking University Atlas from 20 years ago.

The newly-liberated nation picked the Ardagh-Johnson Line (a slightly modified version of Johnson Line) as its official Sino-Ladakh border placing a firm claim on Aksai Chin but not on the sliver of Xinjiang granted by the Peking University Atlas from 20 years ago.

43/50

China annexed Tibet in 1951. This made India uneasy for obvious reasons. To make matters worse, China proceeded to build a highway connecting Xinjiang with Tibet. Part of this road ran through Aksai Chin, south of the Johnson Line but north of McCartney-MacDonald.

China annexed Tibet in 1951. This made India uneasy for obvious reasons. To make matters worse, China proceeded to build a highway connecting Xinjiang with Tibet. Part of this road ran through Aksai Chin, south of the Johnson Line but north of McCartney-MacDonald.

44/50

This made Aksai Chin more accessible to the Chinese than to the Indians who didn& #39;t even learn of the highway& #39;s existence until 1957. What started as the Great Game between Russia and Britain was about to become a far more complicated fight between China and India.

This made Aksai Chin more accessible to the Chinese than to the Indians who didn& #39;t even learn of the highway& #39;s existence until 1957. What started as the Great Game between Russia and Britain was about to become a far more complicated fight between China and India.

45/50

Nehru argued for Johnson& #39;s Line because, "long usage and custom." Zhou (Nehru& #39;s Chinese counterpart) argued for McCartney-MacDonald as it was the only border agreed upon by both British India and China. Sure China never responded to MacDonald& #39;s note, but Hung was Chinese!

Nehru argued for Johnson& #39;s Line because, "long usage and custom." Zhou (Nehru& #39;s Chinese counterpart) argued for McCartney-MacDonald as it was the only border agreed upon by both British India and China. Sure China never responded to MacDonald& #39;s note, but Hung was Chinese!

46/50

The Xinjiang-Tibet highway brought the border dispute to a head and triggered the Sino-Indian War of 1962. China won that round with ease but shelved further work on the highway for later. Only to return later in 2013 when the highway was resurfaced and completed.

The Xinjiang-Tibet highway brought the border dispute to a head and triggered the Sino-Indian War of 1962. China won that round with ease but shelved further work on the highway for later. Only to return later in 2013 when the highway was resurfaced and completed.

47/50

One aftermath of the 1962 war was yet another line: the Line of Actual Control (LAC). This line marks the ceasefire between the 2 belligerents, a de facto border between India and China in the region. It puts Aksai Chin firmly in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.

One aftermath of the 1962 war was yet another line: the Line of Actual Control (LAC). This line marks the ceasefire between the 2 belligerents, a de facto border between India and China in the region. It puts Aksai Chin firmly in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.

48/50

This is where things stand today. A dispute that continues to cost lives and money well into the 21st century, going back 2 centuries and born only because nobody bothered to talk and share notes.

This is where things stand today. A dispute that continues to cost lives and money well into the 21st century, going back 2 centuries and born only because nobody bothered to talk and share notes.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter![[THREAD: AKSAI CHIN]1/50Napoleon Bonaparte and Czar Alexander met on a raft on the Neman River in July, 1807 to sign the first Treaty of Tilsit. Among the terms was Russia invading Britain in return for French support against the Ottomans. [THREAD: AKSAI CHIN]1/50Napoleon Bonaparte and Czar Alexander met on a raft on the Neman River in July, 1807 to sign the first Treaty of Tilsit. Among the terms was Russia invading Britain in return for French support against the Ottomans.](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EY2SfoaVcAA0pjM.jpg)