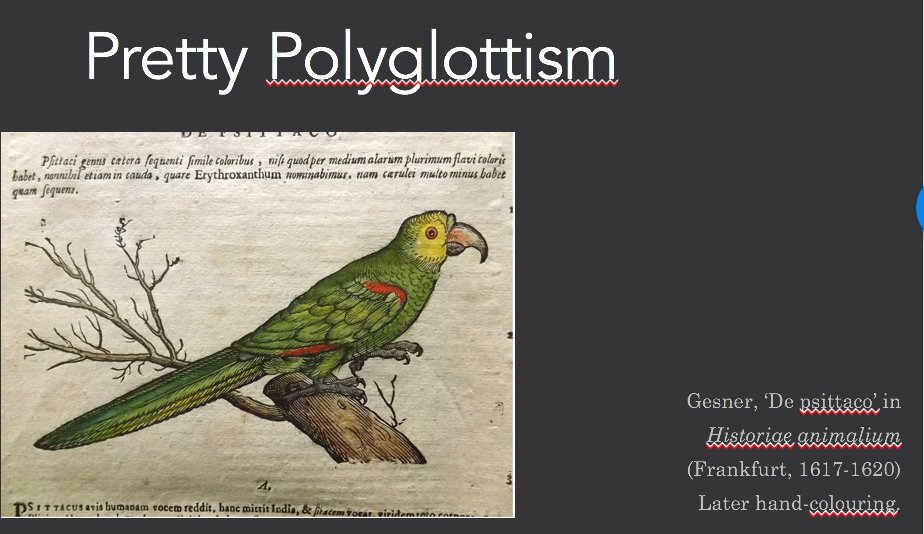

Today, at the #LockdownBestiary, P is for PARROT. This gives this zookeeper an opportunity to revisit interests in parrot language, multilingualism, and the pleasures of nonsense. Or, as I like to call it:

The idea of the polyglot parrot is ancient and modern. In the prologue to the Latin poet Persius& #39;s satires, he asks & #39;quis expedivit psittaco suum chaere?& #39;: who taught the parrot to say & #39;hello& #39;? But & #39;hello& #39; is here in Greek, χαίρε -- the conventional Roman parrot-greeting.

In 2013, the Manchester Evening News ran a story about a Blue Amazon parrot with the byline ‘Multilingual parrot is fluent in Urdu amazing passers-by with his varied vocabulary’. Rocket – the parrot – could & #39;speak& #39; Arabic, Urdu, and English.

https://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/greater-manchester-news/multilingual-oldham-parrot-is-fluent-in-urdu-1307209">https://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/grea...

https://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/greater-manchester-news/multilingual-oldham-parrot-is-fluent-in-urdu-1307209">https://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/grea...

Compare Nigel the African grey parrot, who vanished from his California home but turned up 4 years later, speaking Spanish. Or, as the Guardian has it, ‘Nigel the parrot has said “cheerio” to his British-born owner and “Buenos días” to another family’. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2014/oct/17/missing-parrot-british-accent-speaking-spanish-california">https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandst...

That parrots mimic human articulation makes them seem to communicate; that they are indifferent to the idiosyncratic soundworlds of different languages makes them bafflingly polyglot. I love the final sentence of the article about Rocket:

The parrot& #39;s articulacy also sets it apart from the musicality of other birds. Athanasius Kircher, scoring the voices of birds in his Musurgia universalis of 1650, struggled with the psittacine. It is not possible to represent the parrot onomatopoetically.

The nonsensical and polyglot logorrhoea reaches an extreme in John Skelton& #39;s hilarious, difficult poem & #39;Speke, Parrot& #39;, of c.1521. Parrot, the speaker of the poem, declares his primary characteristic to be his master of the languages of ancient and Biblical scholarship:

But Parrot also speaks French, Dutch, Spanish, English, Welsh, and Irish, at least. The poem itself is macaronic, and at times near nonsense. For a clear sense of its pleasurable bafflements, listen to this brilliant reading by @SebSobecki https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tCckcTHWqKw">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

Skelton is interested in the problem of the parrot, articulate and polyglot without meaning, as a figure for other problems of language: the insincere speech of diplomats and courtiers; debates over how to teach the learned tongues; the cant of scholars; Biblical obscurity; ...

the limitations and potentialities of English as a literary language. His concern with language-learning and the parrot is shared by his contemporary Erasmus, who argues in De pueris instituendis for the teaching of the learned languages from childhood, because:

The association of parrots with nonsense, meanwhile, is shared by John Florio, who, in Worlde of Wordes (1598), his first Italian-English dictionary, defines the phrase ‘pappagallesca lingua’ as ‘the parrats language, as we say pedlers french, gibbrish, or the fustian tongue’.

Another favourite polyglot parrot comes from Sir William Temple, who recounts Prince Maurice of Nassau& #39;s story of a parrot in Brazil which ‘spoke, and asked, and answered common Questions like a reasonable Creature’. The Prince and the parrot have a conversation:

Locke retells the story in the 4th edition of the Essay Concerning Human Understanding, using it to dismiss the Aristotelian definition of man as a rational animal: even if the parrot could use language and reason (which Locke denies), we still couldn& #39;t call it a ‘man’.

I& #39;m more interested, though, in the polyglot anecdote: Locke’s story relates Temple’s story of a story related to him by Prince Maurice, about a parrot in Brazil who is owned by a Portuguese man, who speaks, in both Locke and Temple, in French. Temple addresses the problem:

The story also fascinates because of the parrot’s switch from human language into the clucking of chickens: an ambiguous piece of onomatopoeia, which either imitates the sound of another species, or the imitative sounds made by humans in an attempt to speak ‘chicken’.

Skelton’s Parrot can ‘mewte and crye’ like a cat: the parrot marks its distinction from the inarticulate, animal world by itself imitating the sounds of other languages. No-one asks their children & #39;what does a parrot say& #39;; the answer is, potentially, anything. (Photo:Steven Kaye)

If this thread has read like excerpts from a paper, that& #39;s because it is: or rather, from several papers which at some point I want to assemble into an essay about parrots, polyglottism, imitation, nonsense, and epistemology in the c16th and c17th.

As a result, as is obvious, my material is skewed to what I know -- nothing about real parrots, imported parrots, pet parrots, New World parrots, the natural history of parrots. Please join in, o ye more learned and knowledgeable, and pepper parrots over the Lockdown Bestiary!

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter