Ok, I& #39;m going to try to tackle this right now. (Thread) https://twitter.com/Delafina777/status/1263183437206151168">https://twitter.com/Delafina7...

And again, I& #39;m talking about progressive Christian pastors here. Like, very few people I interact with put any stock in what conservative Christians say, obviously.

The way progressive Christians cling to anti-Jewish rhetoric--and insist that it& #39;s not anti-Jewish--has mystified me for a while.

Some of them will listen to a point--maybe they& #39;ll stop using the Pharisees as a stand-in for everything they don& #39;t like--

Some of them will listen to a point--maybe they& #39;ll stop using the Pharisees as a stand-in for everything they don& #39;t like--

But few of them will ditch the idea of "the religious authorities" of the time as Jesus& #39;s main foil.

So basically, they& #39;re willing to listen to Jews as far as not using specific language, but not as far as the *concept* being problematic (and ahistorical).

So basically, they& #39;re willing to listen to Jews as far as not using specific language, but not as far as the *concept* being problematic (and ahistorical).

And even when you sit down and talk it through with the ones you believe to have good intentions, you often get some version of "well, it& #39;s important to take on the religious authorities of today who are preaching hate."

And that& #39;s true:

I absolutely AGREE that it& #39;s important for Christian clergy to directly tackle hate being preached by other Christians.

But "so if we have to throw (historical) Jews under the bus to do that, so be it" is a deeply ugly ends-justify-the-means approach.

I absolutely AGREE that it& #39;s important for Christian clergy to directly tackle hate being preached by other Christians.

But "so if we have to throw (historical) Jews under the bus to do that, so be it" is a deeply ugly ends-justify-the-means approach.

So I was like, "ok, I think I& #39;ve figured out why they& #39;re clinging to it so hard, and I& #39;ll talk about that."

And then in the meantime, I read Amy-Jill Levine& #39;s chapter, "Christian Privilege, Christian Fragility, and the Gospel of John," in here:

https://www.amazon.com/Gospel-John-Jewish-Christian-Relations/dp/1978703481">https://www.amazon.com/Gospel-Jo...

And then in the meantime, I read Amy-Jill Levine& #39;s chapter, "Christian Privilege, Christian Fragility, and the Gospel of John," in here:

https://www.amazon.com/Gospel-John-Jewish-Christian-Relations/dp/1978703481">https://www.amazon.com/Gospel-Jo...

Which was interesting, because while I love Amy-Jill Levine, I do sometimes get frustrated that her diplomacy in discussing Jewish-Christian relations frequently seems to lead her to ignore power differences between us.

She does, gently, talk about Christian privilege a lot, but for her to *title* something "Christian fragility" seemed unusually confrontational for her.

And then I started reading and, well, the chapter talks a lot about Charlottesville.

And then I started reading and, well, the chapter talks a lot about Charlottesville.

The book is super-spendy and only seems to be available from academic libraries, but she did a lecture at Boston College that& #39;s basically a verbal version of it: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fYOFHZp16c4">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

And as it turns out, here& #39;s a great example of exactly what I& #39;m talking about.

So, at the Unite the Right rally, as you may recall, marchers chanted "Sieg heil," and "Blood and soil," and "Jews will not replace us."

So, at the Unite the Right rally, as you may recall, marchers chanted "Sieg heil," and "Blood and soil," and "Jews will not replace us."

Beth Israel, a Charlottesville synagogue, was refused police protection during the march.

And let& #39;s be clear: the march was in large part about anti-Black racism and anti-immigrant hate. I don& #39;t want to minimize that.

But it was also about hatred of Jews.

And let& #39;s be clear: the march was in large part about anti-Black racism and anti-immigrant hate. I don& #39;t want to minimize that.

But it was also about hatred of Jews.

So of course, the Sunday after, pastors were obviously going to talk about it--which, GOOD. And as it happened, the lectionary reading (at least in some denominations) that week was Jesus and the Canaanite woman, in which he initially gets all racist when she asks for healing.

So Professor Levine searched for transcripts of sermons online and blog entries by pastors from the Sunday after Charlottesville, and discovered that overwhelmingly, they talked about racism. Most didn& #39;t mention the anti-Jewish focus of the marchers.

So far, mildly frustrating--especially given that, as Levine points out, the sermons coming from non-evangelical pulpits are more likely to reinforce anti-Jewish thinking (given that Jews can be read as the villains of much of the NT) than straight-up racism.

Mildly frustrating, yes, but not dangerous, and of course, simply leaving out the anti-Jewish chants of the Charlottesville rally is, to use Christian terminology, a sin of omission, not a sin of commission.

If only they& #39;d stopped there.

If only they& #39;d stopped there.

Levine cites a blog post by a progressive pastor who& #39;s also a seminary professor--so, she& #39;s teaching future pastors *how to preach*. Now, this story has a happy ending--Levine contacted her and she revised the post. Hopefully people read the revised version.

Here& #39;s the revised version. https://www.patheos.com/blogs/ecopreacher/2017/08/8-ways-preach-charlottesville-white-supremacy-racial-justice/">https://www.patheos.com/blogs/eco...

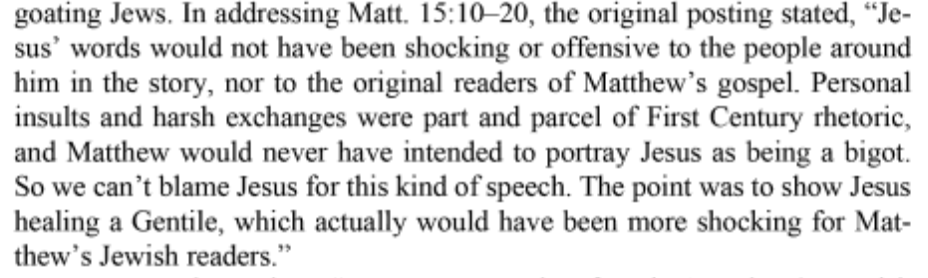

The original version, however, talked about Charlottesville and America& #39;s great national sin of racism, and then said this:

(And given the timeliness of the whole thing, how many people that read the original version returned to see the revisions?)

So, the passage in that screenshot claims that Jesus referring to Canaanite gentiles as "dogs" wouldn& #39;t have shocked his Jewish listeners--they would have seen that as normal--but the idea of Jesus healing a gentile would have shocked them.

I could go into all the reasons that& #39;s historically inaccurate, but that& #39;s a different thread: 1st century Jews would not have found the idea of healing a gentile shocking.

There were Jewish physicians in Rome and Egypt, ffs.

There were Jewish physicians in Rome and Egypt, ffs.

But this take wasn& #39;t uncommon.

So through a neat little rhetorical loop, the scapegoats of the Nazis marching in Charlottesville also become the scapegoats of Christian pastors preaching against the Nazis marching in Charlottesville.

Delightful.

So through a neat little rhetorical loop, the scapegoats of the Nazis marching in Charlottesville also become the scapegoats of Christian pastors preaching against the Nazis marching in Charlottesville.

Delightful.

Levine also goes through the notes on the New American Bible, Revised Edition (NABRE), approved bible of the American Conference of Catholic Bishops.

And despite Nostra Aetate, despite "The Jewish People and their Sacred Scriptures," despite "The Gifts of God Are Irrevocable"...

And despite Nostra Aetate, despite "The Jewish People and their Sacred Scriptures," despite "The Gifts of God Are Irrevocable"...

The notes state that "dogs" and "swine" were normal Jewish insults for gentiles--they& #39;re actually cross-cultural insults used by many cultures, and there& #39;s no evidence of Jews generally calling gentiles dogs (although there& #39;s plenty of examples of Christians calling Jews dogs...)

And more generally, any time someone in the NT--whether Jesus or his disciples--says something nasty, the NABRE decides that this must be a textual addition from Jewish Christians (gentile Christians, of course, being above that sort of thing).

so the homiletic/interpretive equation becomes:

When Jesus says something we like it’s because he was God.

When Jesus suffers or otherwise shows moments of vulnerability, it’s because he was human.

But when Jesus says something we don’t like, it’s because he was Jewish.

When Jesus says something we like it’s because he was God.

When Jesus suffers or otherwise shows moments of vulnerability, it’s because he was human.

But when Jesus says something we don’t like, it’s because he was Jewish.

Levine notes that Rosemary Reuther argued decades ago that "possibly anti-Judaism is too deeply embedded in the foundations of Christianity to be rooted out entirely without destroying the whole structure."

She adds that she& #39;s not there yet.

I& #39;m not sure I& #39;m not.

She adds that she& #39;s not there yet.

I& #39;m not sure I& #39;m not.

But in any case, these are the obvious examples, since at least we& #39;re openly talking about Jews.

Less easy to get people to understand are why when progressive faves like John Pavlovitz insist on comparing contemporary authoritarian Christians to Pharisees, it& #39;s dangerous to Jews--and his refusal to engage with rabbis asking him to stop compounds the problem.

But, thank heaven, at least progressive Christians seem to be *starting* to listen on the Pharisee issue.

Unfortunately, their solution seems to be to keep saying exactly the same thing, but sub in "religious authorities of the time" for "Pharisee."

Unfortunately, their solution seems to be to keep saying exactly the same thing, but sub in "religious authorities of the time" for "Pharisee."

A trendy new solution to the New Testament& #39;s more viciously anti-Jewish passages seems to be subbing in "Judeans" for "Jews."

Adele Reinhartz notes the problems with that here: https://marginalia.lareviewofbooks.org/vanishing-jews-antiquity-adele-reinhartz/">https://marginalia.lareviewofbooks.org/vanishing...

Adele Reinhartz notes the problems with that here: https://marginalia.lareviewofbooks.org/vanishing-jews-antiquity-adele-reinhartz/">https://marginalia.lareviewofbooks.org/vanishing...

So to get back to my original point (yes, all that was context):

why are progressive Christian pastors and thinkers so wedded to the "Pharisees bad!" or "Jesus was killed--or at least In Trouble--for challenging the religious leaders of his time" framings?

why are progressive Christian pastors and thinkers so wedded to the "Pharisees bad!" or "Jesus was killed--or at least In Trouble--for challenging the religious leaders of his time" framings?

And they *are* clinging to it, *hard*:

Even when you point out the problems with the framing, the answer is usually, "well, SOME Pharisees were bad," or "well, yes the Romans killed him, but surely The Religious Authorities Of The Time were upset by him."

Even when you point out the problems with the framing, the answer is usually, "well, SOME Pharisees were bad," or "well, yes the Romans killed him, but surely The Religious Authorities Of The Time were upset by him."

So, first, here& #39;s a whole collection of threads on why the Pharisee framing is bad: https://twitter.com/Delafina777/status/1199934167967924224">https://twitter.com/Delafina7...

I& #39;m not going to rehash it all here, but:

-Nothing Jesus said was outside the norm for what other Pharisees were saying (regardless of what Jesus considered himself to be, his contemporaries would almost certainly have considered him a Pharisee)

-Nothing Jesus said was outside the norm for what other Pharisees were saying (regardless of what Jesus considered himself to be, his contemporaries would almost certainly have considered him a Pharisee)

-Jesus was executed by Romans, via a Roman method of execution, for a Roman crime (they even put a handy label on his cross about it)

And the 101 learning on this is that the Pharisees (the ancestors of modern rabbinic Judaism) were almost certainly cool with Jesus, and early Christian polemic against them is an obsolete historical spat that should be left in the 1st/2nd centuries.

I mean: you won.

The vast majority of the world knows everything they know about Jews because of what CHRISTIANS say about us. We can& #39;t really stop you from claiming *our* history, saying whatever you want about us. There aren& #39;t enough of us to be anywhere near as loud as you.

The vast majority of the world knows everything they know about Jews because of what CHRISTIANS say about us. We can& #39;t really stop you from claiming *our* history, saying whatever you want about us. There aren& #39;t enough of us to be anywhere near as loud as you.

So the idea that you need to keep preaching the passages of the NT that treat Jews as competitors is--not grave-dancing, since despite your best efforts, we still exist--but dancing on the body of someone you& #39;ve beaten pretty severely.

Anyway, the problem that continues to exist in progressive Christian circles is defining Jesus over and above his Jewish context. Everything he says has to be radical and challenging to his audience, so his context has to serve as a foil for him.

If Jesus preaches about caring for the poor, the thinking goes, his audience must have been primarily concerned with contempt for the poor or, at least, reverence for the rich.

What he was saying HAD to be radical.

What he was saying HAD to be radical.

And the logical endpoint of this thinking--which, to be clear, very few progressive Christians are willing to say out loud, and most probably aren& #39;t even following to its endpoint--is that Judaism is the problem Jesus came to solve.

You see this a LOT in how parables get preached. https://twitter.com/Delafina777/status/1199566137677107200">https://twitter.com/Delafina7...

It& #39;s understandable:

Progressive pastors are frequently fighting the perception that Christianity is inherently conservative, that the religious authorities of today--mostly evangelical Christians--have the right of it.

Progressive pastors are frequently fighting the perception that Christianity is inherently conservative, that the religious authorities of today--mostly evangelical Christians--have the right of it.

They& #39;re engaged in a struggle for legitimacy, much as the writers of the NT were.

The power progressive (American) Christians are fighting against *is* largely religious authorities--because in the contemporary US, religious authority and state power are deeply intertwined.

The power progressive (American) Christians are fighting against *is* largely religious authorities--because in the contemporary US, religious authority and state power are deeply intertwined.

So it& #39;s a very easy move to map the struggle of Jesus/the NT writers/early Christians onto the struggle of progressive Christians today, and vice versa.

And the obvious, almost inherent, move there is to conflate religious authority figures of both times.

And the obvious, almost inherent, move there is to conflate religious authority figures of both times.

The problem is that while there are some obvious parallels, the political/religious situation in the contemporary US is *nothing like* that of 1st-century Judea.

Religious and political authority *weren& #39;t* particularly wedded in 1st-century Judea.

The "religious authorities" were still Jews living under a brutal, foreign, occupying power. The Pharisees were the popular religious authorities, the Sadducees the institutional ones.

The "religious authorities" were still Jews living under a brutal, foreign, occupying power. The Pharisees were the popular religious authorities, the Sadducees the institutional ones.

But how much "religious authority" they had under Roman power is pretty debatable. They didn& #39;t have state/military power.

And, like, look, usually when I talk about Pharisees and Jesus I let the Sadducees be the bad guys, because the High Priest was a Roman puppet, and it& #39;s hard enough to get Christians to the 101 level of "no, the Pharisees weren& #39;t hypocritical legalists who hated Jesus."

But the 201 level there is that most Sadducees--even, probably, the High Priest--were Jews who& #39;d seen friends, neighbors, and family brutally murdered by Romans and were *trying to keep their people alive.*

We can quibble over whether appeasement was a valid strategy, but

We can quibble over whether appeasement was a valid strategy, but

...given that if you want to draw analogies, most Americans are Romans living in Rome rather than Jews living under a brutal occupying power, we don& #39;t *know* what we& #39;d consider valid in their situation.

(Incidentally, the only way to read Jesus& #39;s "trial" before the the High Priest that doesn& #39;t collapse into a mass of conflicting details (if you know anything about history) is that it was designed to try to get Jesus to recant before going into Roman custody.

Whether they were doing it because they cared about him and were trying, as they saw it, to save him from his fool self, or because they were just afraid that he was going to get another several thousand Jews crucified with his apparent sedition, who knows.

Highly recommend Haim Cohn& #39;s "The Trial and Death of Jesus" on this topic.)

But the point is, rather than political and religious authority in 1st-century Judea being happily in bed with each other, like they are in America right now, the political authority had almost all the power, and viewed even the religious authority they were trying...

...to suborn with contempt and suspicion. And the Pharisees--who most of the common people viewed as having genuine moral standing and spiritual authority--wanted the Romans gone and were potentially breeding sedition. They were *fighting* the power.

So as tempting as it is to draw parallels between:

contemporary progressive Christians fighting back against religious/political authorities preaching hate and reifying oppression

and

Jesus being a rebel against ...?

contemporary progressive Christians fighting back against religious/political authorities preaching hate and reifying oppression

and

Jesus being a rebel against ...?

It ultimately turns an oppressed, occupied people into the power God supposedly came to earth to oppose.

Levine pegs this problem as "weak Christology," which I am coming around to, although I think it& #39;s more complicated than that.

Basically: you don& #39;t need to make Jews and Judaism look bad to make Jesus look good. He looks fine on his own.

Basically: you don& #39;t need to make Jews and Judaism look bad to make Jesus look good. He looks fine on his own.

It would be nice if the solution were that simple, but I don& #39;t think it is.

Basically, the problem remains: if you& #39;re insisting that what Jesus was saying was somehow *different* from what everyone else was saying, you& #39;re still treating Judaism as the problem he came to solve.

Basically, the problem remains: if you& #39;re insisting that what Jesus was saying was somehow *different* from what everyone else was saying, you& #39;re still treating Judaism as the problem he came to solve.

But if you DON& #39;T treat what he said as special, what& #39;s left?

(as far as I can tell, what& #39;s left is...

everything that separates Christianity and Judaism: his divinity, his sacrifice, and salvation)

(as far as I can tell, what& #39;s left is...

everything that separates Christianity and Judaism: his divinity, his sacrifice, and salvation)

At some level, Christians really want (and maybe even really *need*) Jesus to have showed up to lecture Jews on being nicer to gentiles, bc Christians *are* gentiles and the entire theology rests on the idea of Israel& #39;s blessing being transferred--or at least shared--w gentiles.

I mean, my reaction is basically, "wow, if you think that God, for the one and only time, came to earth in human form to suffer and die to bring a message to humanity, that message was that a tiny group of occupied and oppressed people needed to be nicer?"

My question is, if you believe that Jesus was God:

what if the importance of what Jesus was *saying* (as opposed to what he was *doing*) wasn& #39;t that it was so insightful that only God could say it?

What if God had to come say it *too*?

what if the importance of what Jesus was *saying* (as opposed to what he was *doing*) wasn& #39;t that it was so insightful that only God could say it?

What if God had to come say it *too*?

Because again, most of what Jesus did was just quote or paraphrase the Torah, and say things that most of the Pharisees were also saying.

To make what he was saying special/unique, you have to--ahistorically--ignore what they were saying, and make Jews out to be evil/stupid.

To make what he was saying special/unique, you have to--ahistorically--ignore what they were saying, and make Jews out to be evil/stupid.

On the other hand, you can harmonize it all and still believe he was God if instead of "don& #39;t listen to them, listen to me" his position was "fine, *I*& #39;ll say it, and I& #39;m literally God--are you listening NOW?"

Of course, that still potentially assumes that the people who needed to hear it were Jews in particular, not, y& #39;know, the world in general.

And I assume the attachment to the idea that God came to earth in the form of Jesus in order to lecture the Jews about being more accepting of gentiles, as well as the insistence on the idea that Jesus was at odds with the religious authorities of his day...

...largely boils down to the fact that even if the heroes of the Gospels are Jews (proto-Christian Jews, of course), the audience is predominantly gentile. (And the gentiles in the story are mostly Roman, hence the textual backflips the NT does to exonerate them.)

So even though Jesus was Jewish, the Jews are still Other (the West& #39;s most enduring and familiar Other, in fact), while the (Roman) gentiles are Self for gentile readers.

Hence the attachment to the idea of Jewish religious authorities that Jesus is rebelling against.

Hence the attachment to the idea of Jewish religious authorities that Jesus is rebelling against.

And I think 2000 years of that self/Other distinction continue to be at play even for progressive Christians who think they& #39;ve internalized the idea that Jesus was Jewish.

If the (predominantly evangelical) Christians who are embracing (and spreading) hate and white supremacy, and have religious and political authority in the US, are to be Other (nb: the "fake Christian" framing, on which @C_Stroop has done a LOT of work): https://twitter.com/C_Stroop/status/1242664278252896257">https://twitter.com/C_Stroop/...

...the authority against which Social Justice Jesus was preaching must be both religious and Other.

and hence we& #39;re back to Jews as the villains--even if they simply say "religious authorities of the time."

and hence we& #39;re back to Jews as the villains--even if they simply say "religious authorities of the time."

And the erasure of Jews as targets of the Charlottesville Nazi marches.

Because ultimately, when you gotta preach against evangelical, white supremacist Christian religious authorities, and you want to position yourself as being on Jesus& #39;s side, it& #39;s easiest if Jesus& #39;s enemies look as much as possible like yours.

And if that ends up throwing Jews under the bus, well, isn& #39;t it more important to have a compelling sermon, or blog entry, or Twitter thread about fighting hate with nice, easy parallels than it is to care about all those complex, messy, historical details?

BTW as far as Jesus& #39;s and his followers& #39; relationships with Jewish "religious authorities" (primarily the Temple), here& #39;s another good resource: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lksnynNv6UU">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter