Welcome to an episode of #DeafHistorySeries!

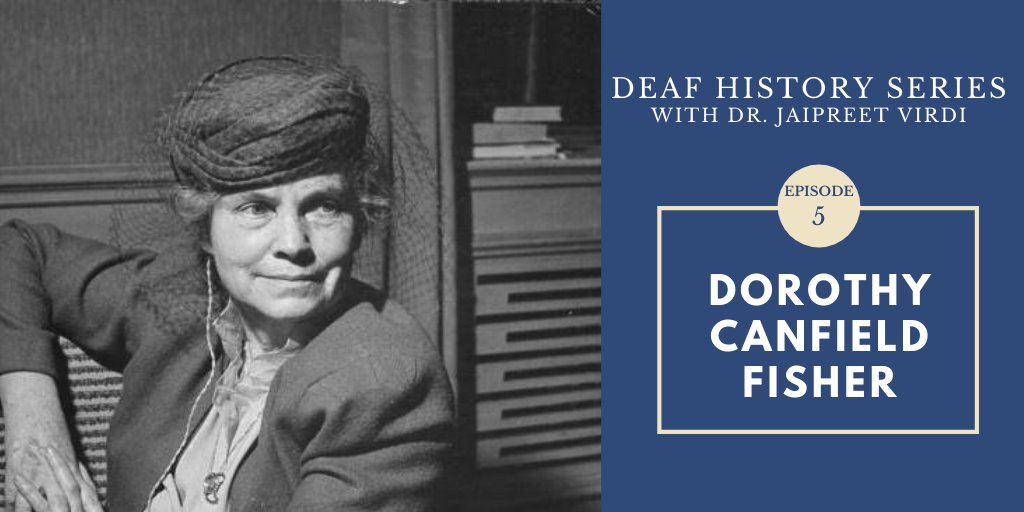

Reformer & activist, Dorothy Canfield Fisher (1879-1958) had a busy life: she wrote 40 books, spoke 5 languages, led WWI relief efforts, managed education programs & promoted prison reform. She also spent decades hiding her deafness.

Reformer & activist, Dorothy Canfield Fisher (1879-1958) had a busy life: she wrote 40 books, spoke 5 languages, led WWI relief efforts, managed education programs & promoted prison reform. She also spent decades hiding her deafness.

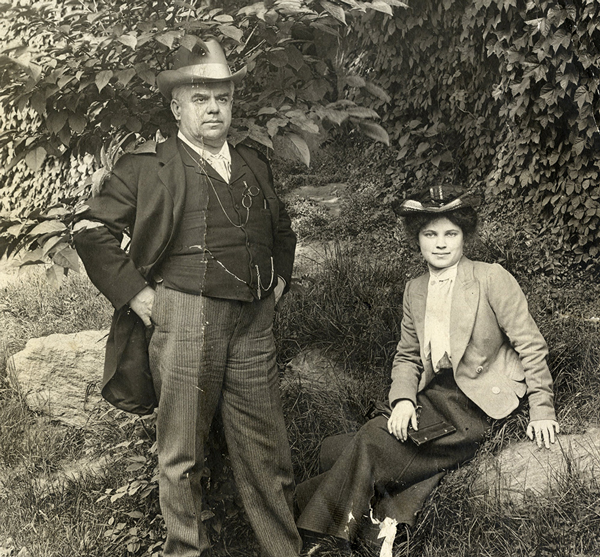

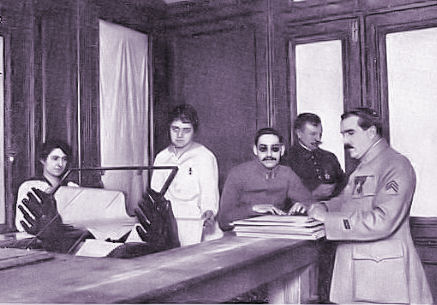

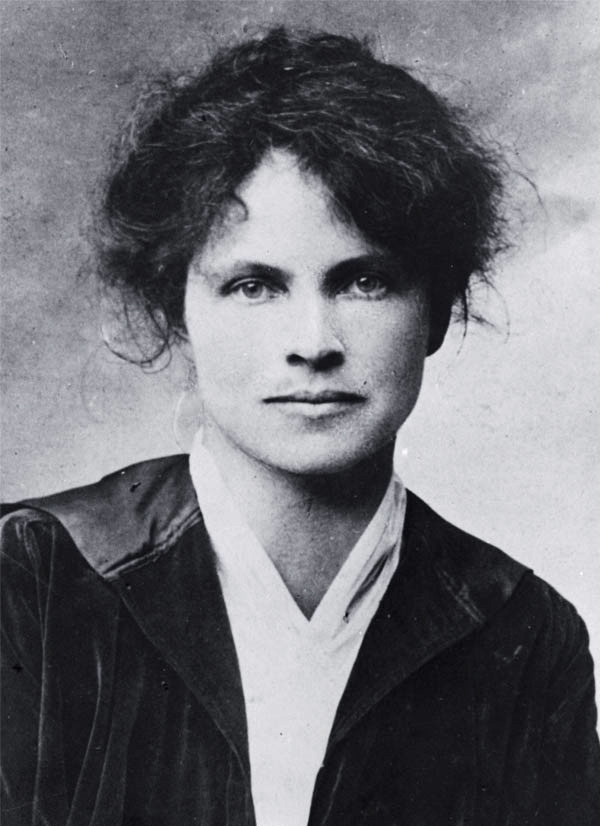

Dorothy was born on February 17 1879 to economics professor James Hulme Canfield (pic1) & artist Flavia Camp (pic2), a couple who were outspoken advocates of women’s rights & Progressive causes. She was named after Dorothea Brooks, the heroine of George Eliot’s novel Middlemarch.

Dorothy’s youth was marked with regular travels to France & middle ear infections. By 14, the infections left her deaf.

For the rest of her life, she refused to talk or write about her deafness & when asked, she replied she found her deafness to be “a hinderance in every way.”

For the rest of her life, she refused to talk or write about her deafness & when asked, she replied she found her deafness to be “a hinderance in every way.”

Lip-reading helped Dorothy adjust to her deafness. She received her BA in literature from Ohio State University & PhD in Romance languages from Columbia University, a rare occurrence for women during her time.

After graduation she worked at the progressive Horace Mann School.

After graduation she worked at the progressive Horace Mann School.

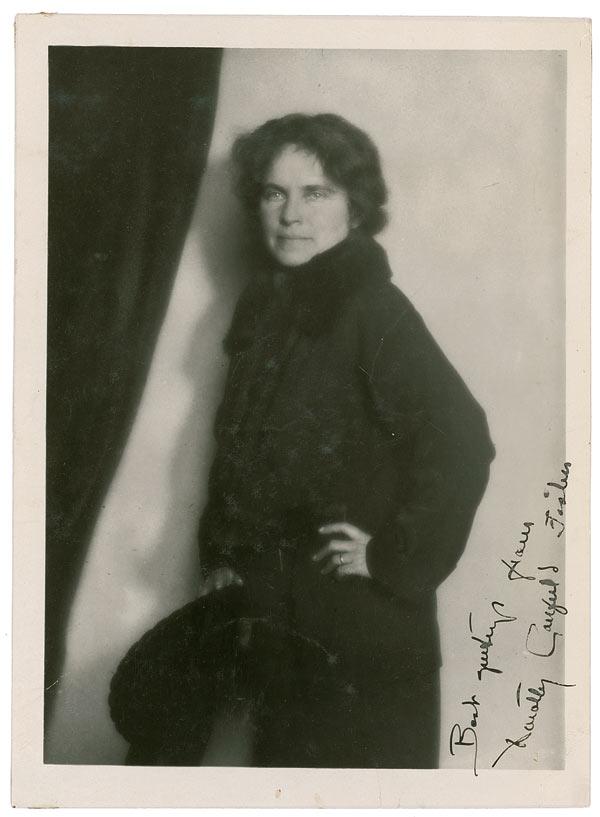

On May 9, 1907, Dorothy married Columbia graduate John Redwood Fisher. The same year she published her first novel, Gunhild.

The Fishers would then settle in Arlington, Vermont, where Dorothy inherited a family farm. The couple would soon have a daughter, Sally, and son, Jimmy.

The Fishers would then settle in Arlington, Vermont, where Dorothy inherited a family farm. The couple would soon have a daughter, Sally, and son, Jimmy.

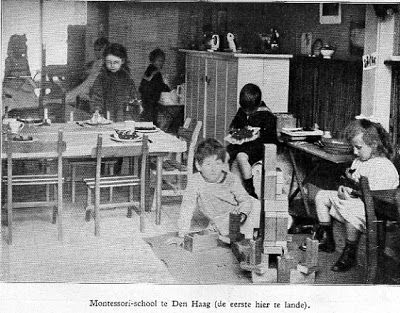

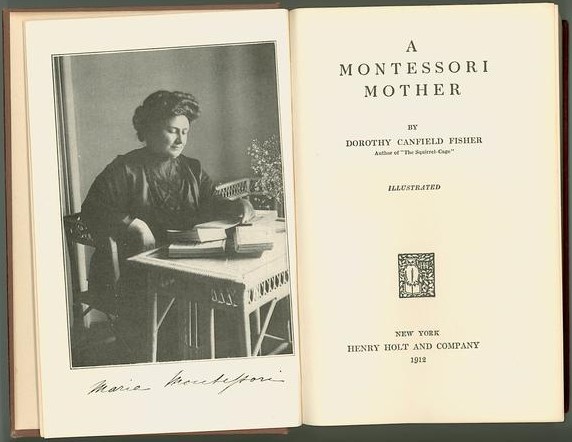

Visiting Rome in 1911, Dorothy learned about the children’s houses established by educator Maria Montessori. Impressed, Dorothy brought the child-rearing method back to America. She translated Montessori’s work & published her own, including The Montessori Mother (1913).

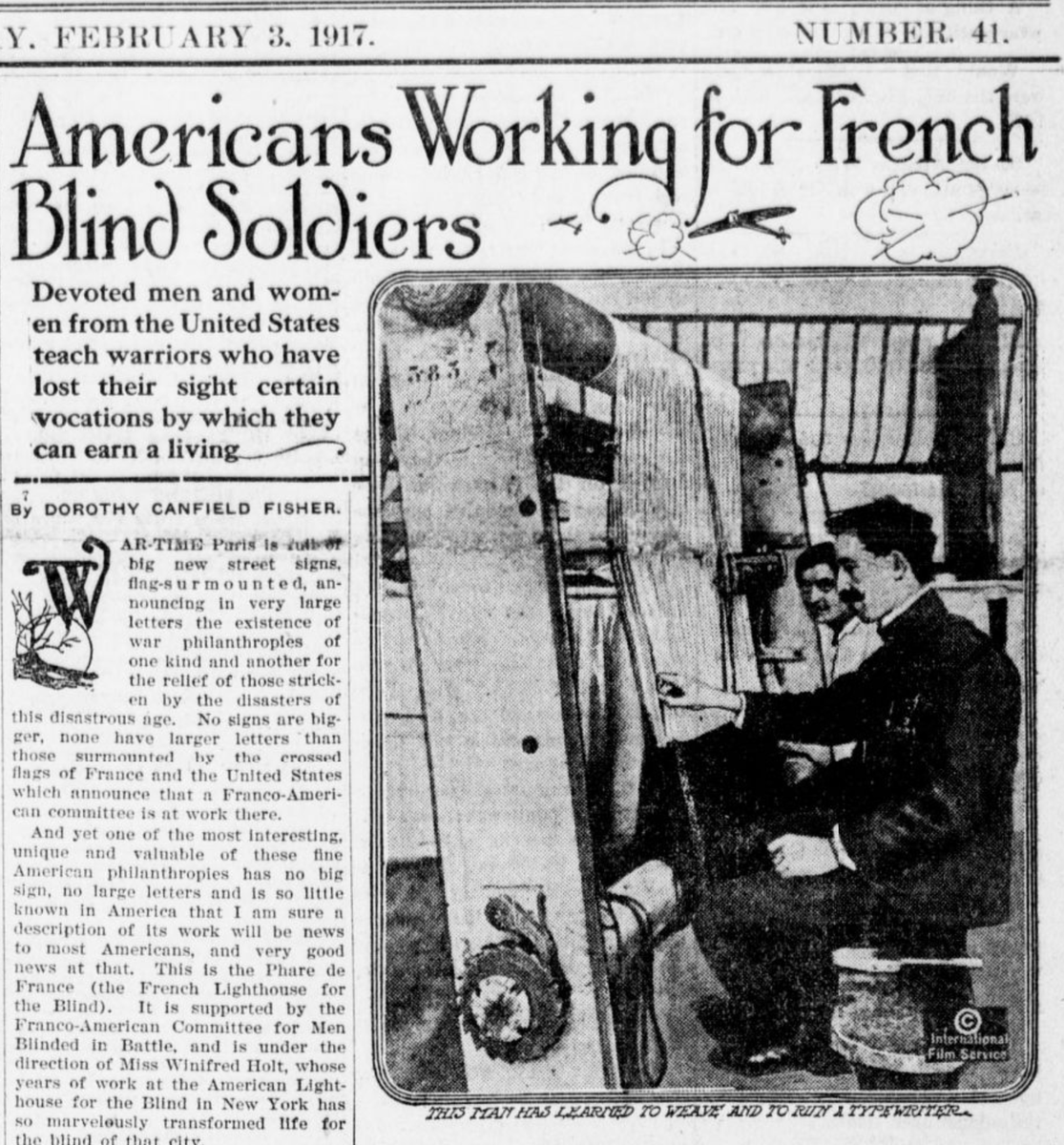

In 1916 the Fishers moved to France to service the Great War. John worked for the ambulance service while Dorothy engaged in relief programs. She established a home for refugee children, a Braille Press for blinded veterans to work &edited a war magazine for disabled soldiers.

After the war, the family returned to Vermont. Channeling trauma in her writing, Dorothy weaved autobiographical motifs on human nature & war, even commenting on disability: “Our senses are not ourselves; we are not our senses. No, they are the instruments of or understanding.”

Around 1919, Dorothy began wearing a hearing aid discreetly.

She still refused to discuss her deafness but was considered by deaf/HOH people as a success. Journalist Laura Davis asked Dorothy in 1922 if she had any advice for deaf people: “Yes, tell them to learn lip-reading.”

She still refused to discuss her deafness but was considered by deaf/HOH people as a success. Journalist Laura Davis asked Dorothy in 1922 if she had any advice for deaf people: “Yes, tell them to learn lip-reading.”

For the next two decades, Dorothy immersed herself in various social causes. She promoted prison and education reform, championed women’s rights, sponsored emigration assistance to Jewish professionals & even headed U.S. committee that eventually pardoned conscientious objectors.

One of the most popular writers of her time, Dorothy addressed her social work in her writing, highlighting themes of economic inequality, class distinctions, racial prejudice & gender discrimination.

Eleanor Roosevelt even named Dorothy 1 of 10 most influential women in the US

Eleanor Roosevelt even named Dorothy 1 of 10 most influential women in the US

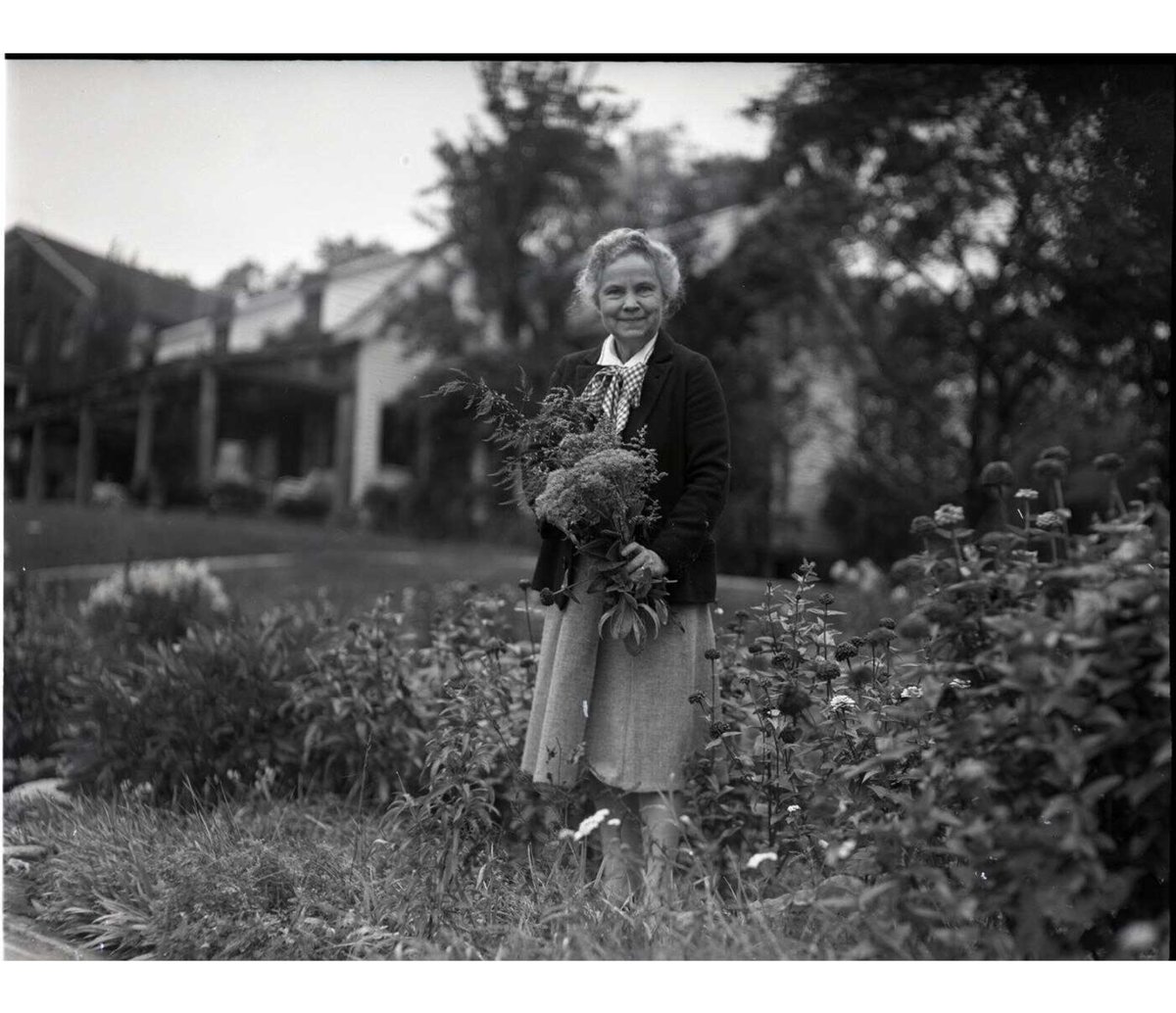

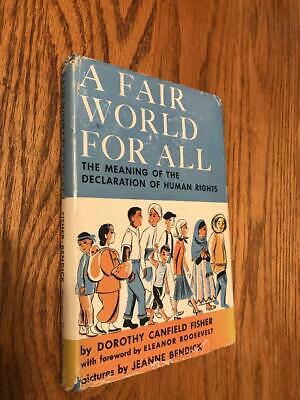

Dorothy’s fondness for Vermont & country life gave her the nickname “Vermont’s First Lady" as she often wrote about Vermont life. She also drafted an educational pamphlet “A Fair World For All” to disseminate ideas of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights more widely.

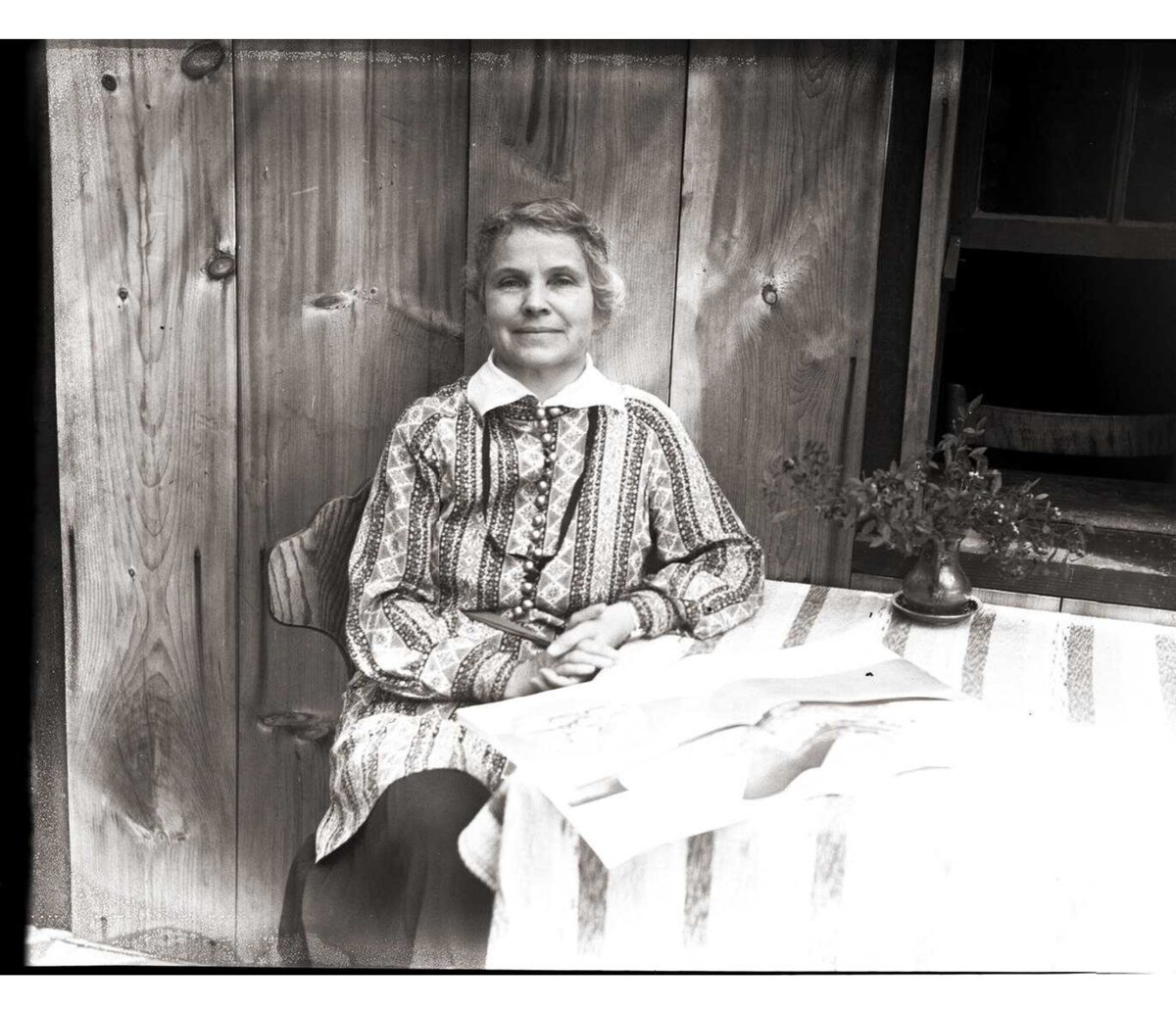

Seemingly, it is also around this period Dorothy stopped hiding her deafness. Editorial photographs like this one show her wearing hearing aids – likely powerful vacuum tube models – which, combined with her lip-reading skills, would have improved her acoustic sensibilities.

Apparently, Dorothy might have been involved in the eugenics movement in Vermont. In 2017, a scholar argued that the writer’s claims about French Canadians & Native Americans were part of broader thoughts about sterilization.

This issue is still debated: https://www.benningtonbanner.com/stories/institutions-relatives-respond-to-dorothy-canfield-fisher-controversy,514698">https://www.benningtonbanner.com/stories/i...

This issue is still debated: https://www.benningtonbanner.com/stories/institutions-relatives-respond-to-dorothy-canfield-fisher-controversy,514698">https://www.benningtonbanner.com/stories/i...

Dorothy Canfield Fisher died at home in Arlington, Vermont on 9 November 1958 from a stroke.

Upon her death, Eleanor Roosevelt remarked: “Mrs. Fisher was a woman of great spiritual perception, and for many years it has given me comfort.”

Upon her death, Eleanor Roosevelt remarked: “Mrs. Fisher was a woman of great spiritual perception, and for many years it has given me comfort.”

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter