Ahem, #twitterstorians, historians and method, a thread in 19 (following) tweets. https://twitter.com/VileHistorian/status/1263875526667763714">https://twitter.com/VileHisto...

I’ve been saying for years that we should be more explicit about history method, but not very loudly. Mostly I’ve said it to grad students or muttered to myself at conferences. Oh, yes, and to my undergraduate research methods class. Saying it to students definitely counts. 1/

To model my commitment, my last book included an appendix that spelled out how I researched my (novel) topic. I meant it as a guide to future scholars. But that short essay was basically a source roadmap, not a complete account of my methods. 2/

When I was in graduate school, back in the last millennium, my mom used to ask me how I knew what notes to take. I never had a good answer. As an instructor, my favorite classes work through the research process step-by-step. There is method to my pedagogical madness. 3/

What is history method? It is helpful to reframe this question in two ways. 1) Know that historians use “methods,” plural, not just “method.” 2) Ask WHERE methods are in research, rather than what THE method is. 4/

Historians love narrative; we tend not to make methods explicit because it would interrupt our storytelling. We just point to sources in our beloved footnotes. But history methods are embedded in conceptualization, research path, workflow, analysis, writing, and ethics. 5/

History methods are conceptualization. What is your project? What’s included? What’s excluded? When does the study begin and end? Historians always want to go backwards in time. How do you know how far back to go? Only #envhist seems to go back “to the beginning.” 6/

Another piece of history methods is research itself: knowing where to look for primary sources, what order to read them, deciding when to move on. Social scientists call this “design” and sometimes talk about “saturation.” I must confess that historians could do better here. 7/

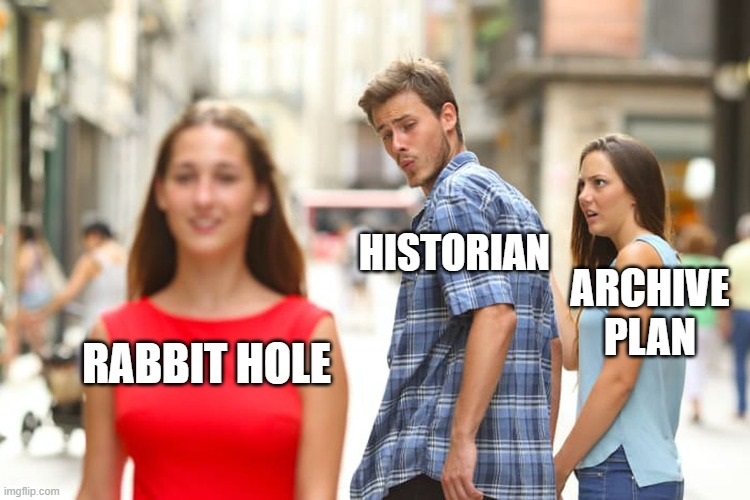

My own impulse has always been to look at everything I can find; or else to limit my research trip according to my budget. I also try to be pretty disciplined about not going down attractive rabbit holes, sometimes to my later regret. 8/

None of these approaches are particularly sound, but they happen all the time. It’s impossible to know in advance exactly what you are going to find in an archive. And you don’t really know what’s relevant until writing (more below). We live quietly with this dilemma. 9/

Workflow, including organizing your notes, is another important part of history research methods. In the 1990s when I did my PhD, I never heard of workflow. I typed notes a laptop and rarely paid (25¢/pg) for photocopies. But it’s increasingly important in the #dighist era. 10/

Carrying a camera into the archive means that you can capture a lot more stuff. Do you shoot everything? How will you store, organize, and tag your notes (or files)? Do you take the time to think about what you are finding while in the archive, or are you a copy machine? 11/

Next up: analysis as a part of history research methods. I used to think analysis=thinking. It’s not a set of standardized procedures, unless you are doing quantitative research or distant reading and you have to know how to regress or code. 12/ http://www.themacroscope.org/2.0/ ">https://www.themacroscope.org/2.0/"...

But historical analysis is really an iterative process, sometimes informed by theory. You work through your evidence, draft commentary on what it means, go back to the notes, find new secondary sources to contextualize your study. If history methods have a core, this is it. 13/

My best understanding historical analysis as iterative comes not from a historian, but from sociologist Andrew Abbott’s DIGITAL PAPER. When I’m reading DP, I wonder why I ever read anything else 14/ https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/D/bo18508006.html">https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books...

Writing as history research methods. This seems like a more active version of thinking. Your decisions about scale, period, connections, omissions, glosses, future projects are all embedded in your prose and all constitute part of your methods. Iteratively. 15/

Finally, ethics as method, researching and writing with integrity: Listen when your sources speak to you; fit your interpretation to your sources, not the other way around; don’t plagiarize or falsify. 16/ https://twitter.com/AmandaISeligman/status/1118672298398105602">https://twitter.com/AmandaISe...

Every single step of this process is hard, and harder to do well. Even methods you aren’t using consciously and critically shape the final version of your work. 17/ https://twitter.com/AmandaISeligman/status/1263871446331383816">https://twitter.com/AmandaISe...

In the 21st century it behooves scholars of all disciplines to do more to publicize our methods. It’s not enough for the public to rely on credentials when they encounter conflicting opinions. Understanding how we know what we know will help them know whom to believe. 18/

Glad to have gotten this off my chest. My apologies for failing to cite scholarship out there about history methods; my reading is idiosyncratic and sometimes too narrow. Many methods discussions are embedded in subfields I’m not exposed to often enough. Please share yours. /fin

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter