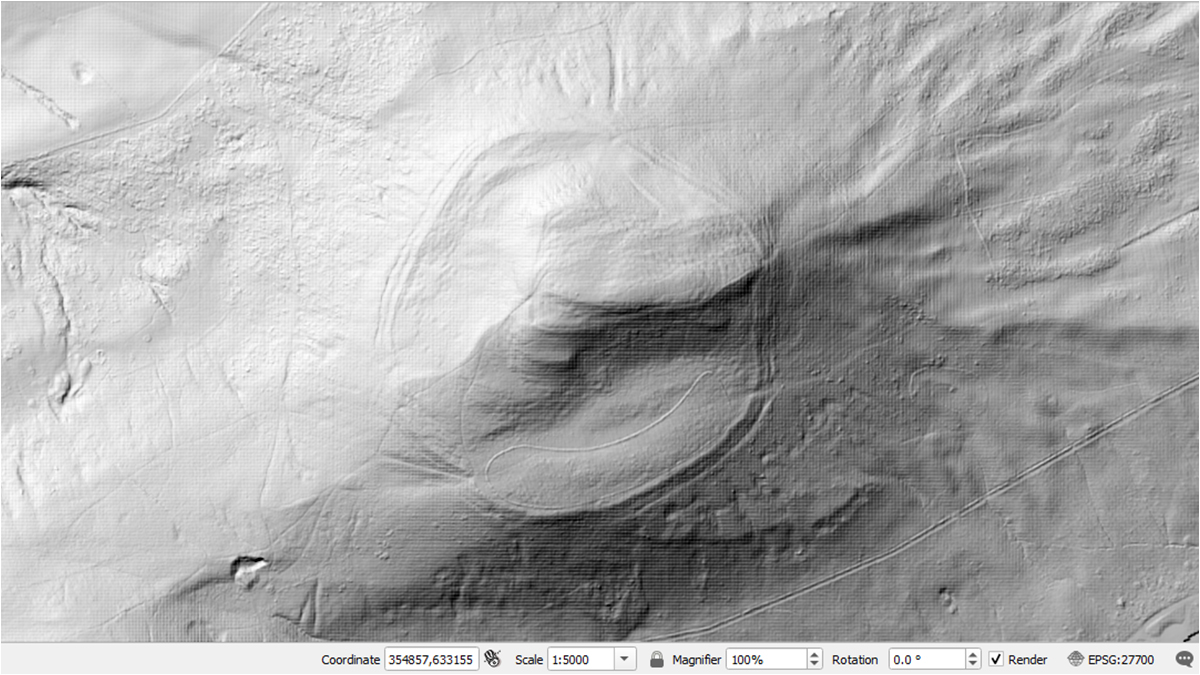

Lots of posts these days about archaeology visible in air photos and lidar. Great to see so much free access to these resources. Many of these posts focus on the ‘bling’ like Eildon Hillfort here. So, I thought it was time for a thread looking at the more mundane. 1/34

Around 11,500 years ago the North of Britain emerged from the last glaciation. The ice had covered almost the whole of N. Britain and scraped the land clean of signs of earlier human occupation. Here, short, narrow drumlins align showing the path of the ice. 2/34

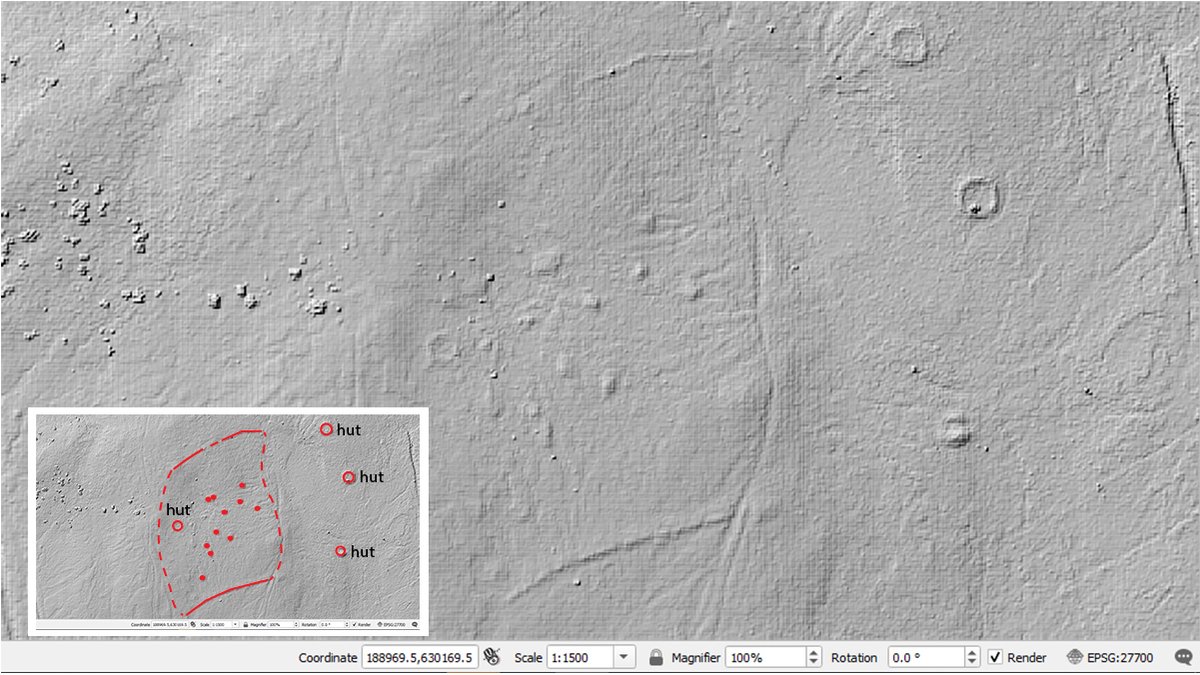

Once the ice had gone the land was often littered with stone. Early farmers needed to clear this. The simplest way to clear the stone was to throw it into piles (archaeologists call these clearance cairns). The early farmers are cultivating the land between these cairns. 3/34

The climate for early farmers enabled them to cultivate at high altitudes. This means that early agricultural landscapes can be found preserved in hill moorland. In lowlands this early farming is likely to be masked by mod farming, only occasionally showing as cropmarks. 4/34

Early fields are often unenclosed. The modern world is so enclosed it& #39;s hard for us to imagine not enclosing our space but, it looks like enclosure for early agricultural communities was more about practicalities, the main one being keeping animals separated from the crops. 5/34

Other concerns might have been to consume stone. This image is just another enclosure. I am not suggesting this one was built to consume stone, but it is interesting that there are very few cairns within it. 6/34

Enclosure to shelter crops from the weather may have been another concern. Again, this image is just an enclosure. I’m not suggesting this one is a weather break. Note how, unlike those above, this enclosure has a house at its centre. 7/34

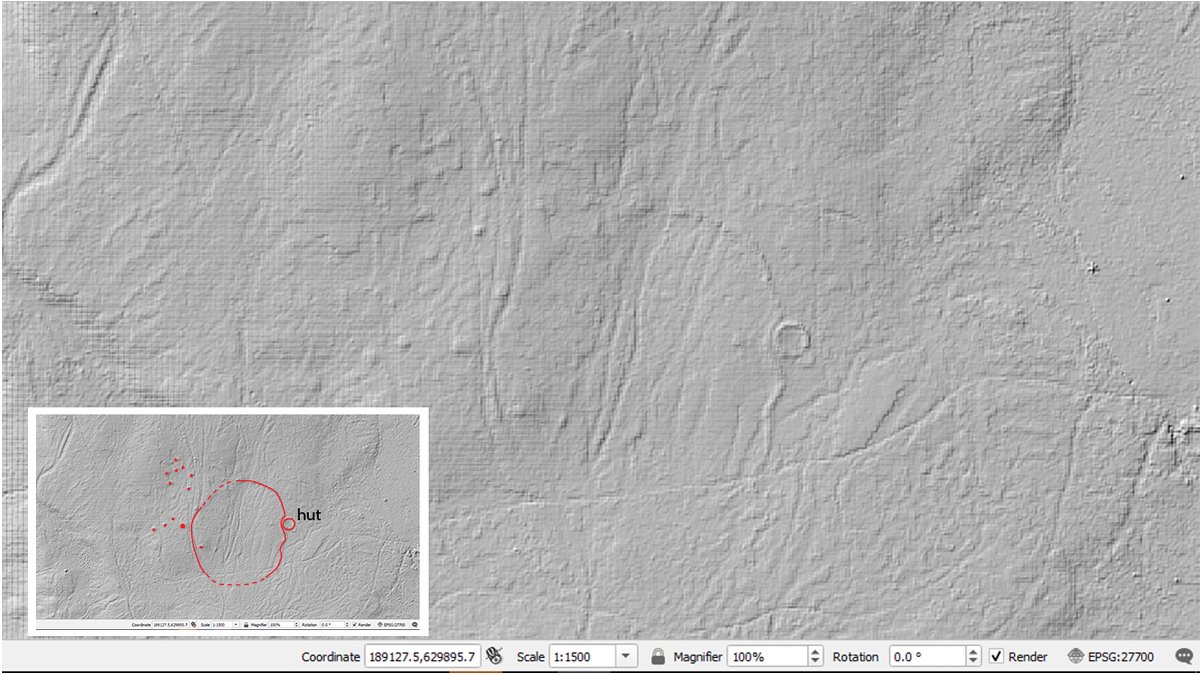

Since these early farms were built, the damp, north Atlantic climate of N Britain has provided a perfect environment to encourage peat growth. Many of these early farming landscapes are submerged beneath the peat with only fragments showing on ridges between the peat basins. 8/34

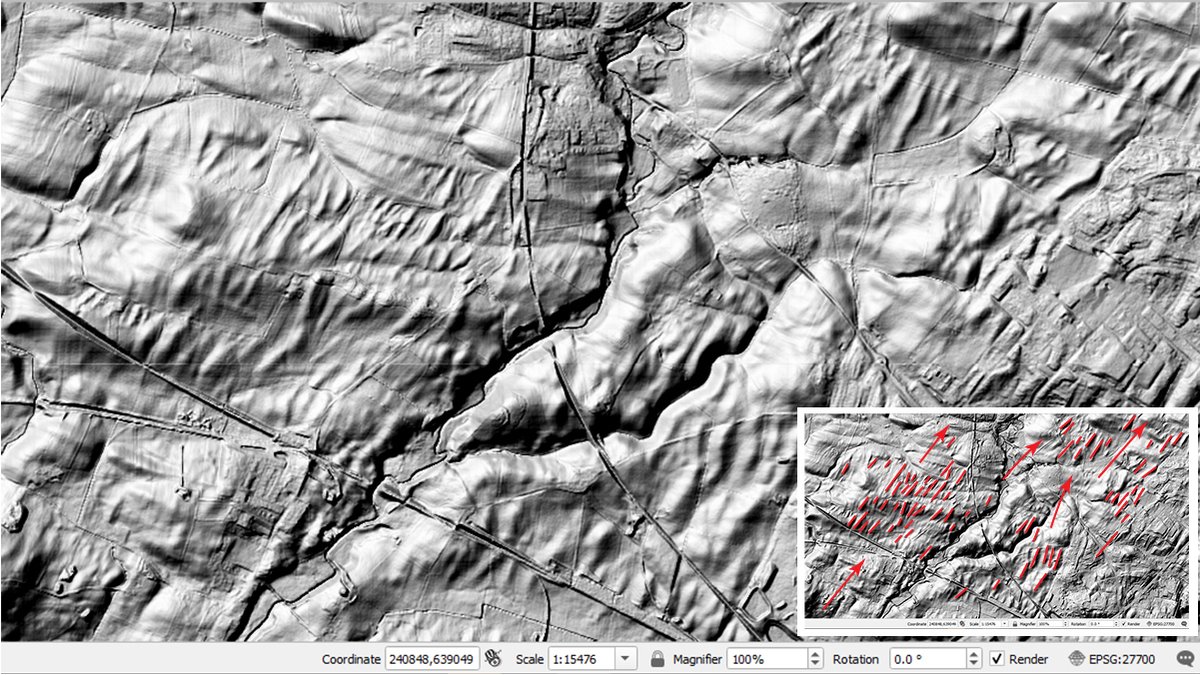

The climate deteriorated around two thousand years ago causing a lot of later prehistoric agriculture to retreat from the higher ground. But wait! Here’s a settlement on a hill and look at the fields around it. Fields containing narrow, straight ridges known as cord rig. 9/34

Cord rig is very rare. These are spade dug ridges that tend to align up and down the slope. Here the patches of rig are separated by paths. 10/34

Early med agriculture is near invisible, it likely retreated from the higher ground and is now hidden beneath modern cultivation. Some houses become long with round ends. Excavation has revealed the development of the kiln barn, hinting at a continued wet climate. 11/34

In the medieval period, the plough pulled by a team led to the creation of distinctive reverse-s shape fields caused by the team’s turning-circle. Fields are long and narrow. The rigs and furrows develop over time as a result of being ploughed in the same direction. 12/34

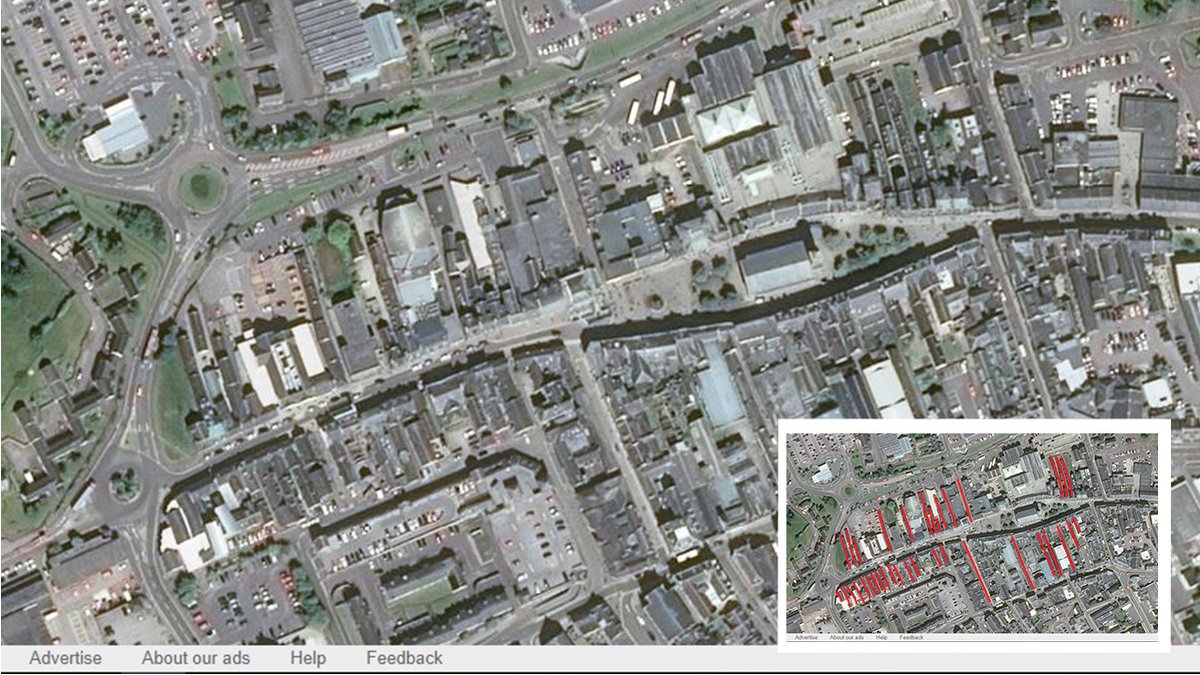

Tenants would farm individual strips rented from the landowner with strips allocated annually. At the founding of the burghs, individual strips were sold to merchants preserving their distinctive form in the urban layout of towns even today. Here we see them in Elgin. 13/34

And here, in Elgin again, we see the strips over a much larger area. The sinuous, reverse-s shapes are preserved in the roads. 14/34

While here in St Andrews the strips are preserved in an area developed in the early 20th century. The earlier strips now delineate the development plots and roads. 15/34

In areas more suited to a mixed system of agriculture an infield – outfield system develops. Infield, within a head dyke, globular fields develop, while common land in the outfield is used for seasonal grazing; the dykes and walls keeping animals away from valuable crops. 16/34

The farmstead, barns and byres in the infield can often be found clustered together in “ferm-touns”. As with the lowlands, those farming the land are tenants leasing the land annually. 17/34

The infield in the NW is often distinctive because of the deep, spade dug, “lazy-beds”. These indicate potatoes were cultivated. Grains and kale would be cultivated in smaller walled enclosures to protect them from the weather. 18/34

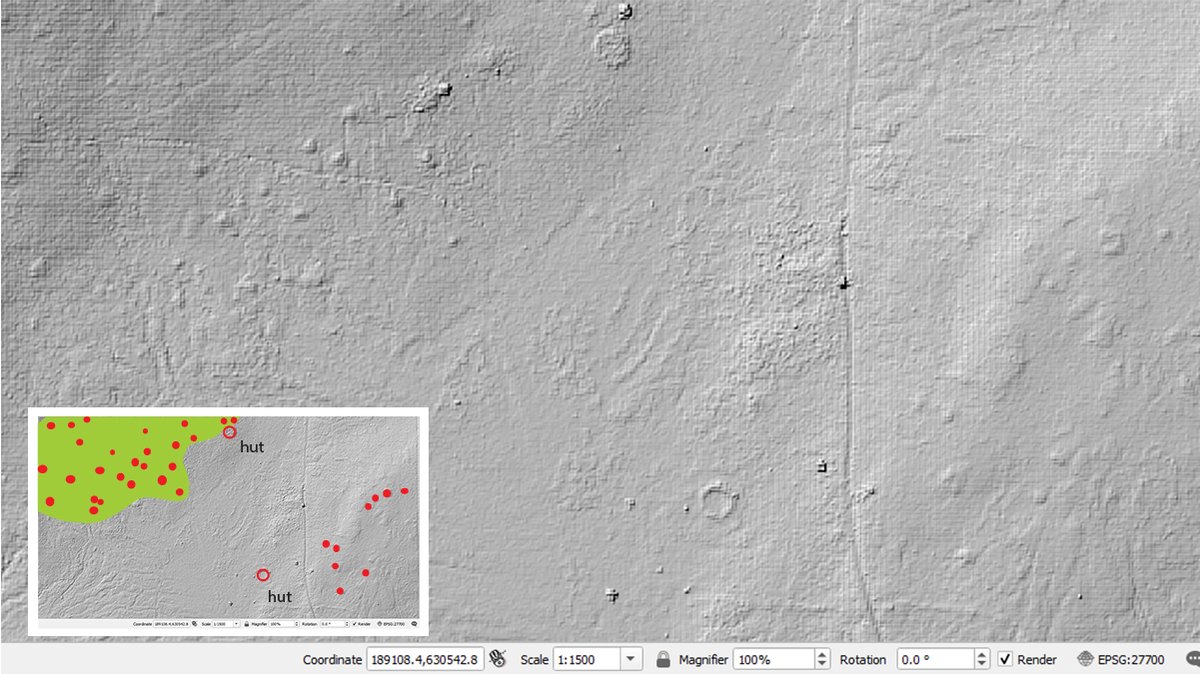

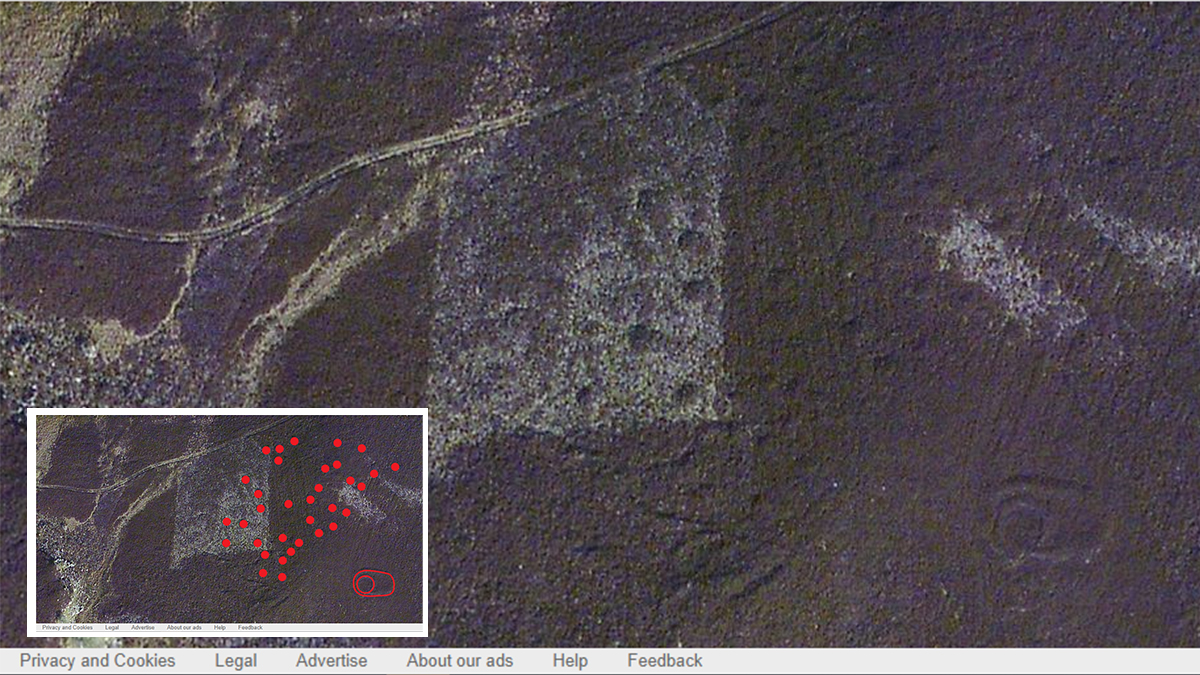

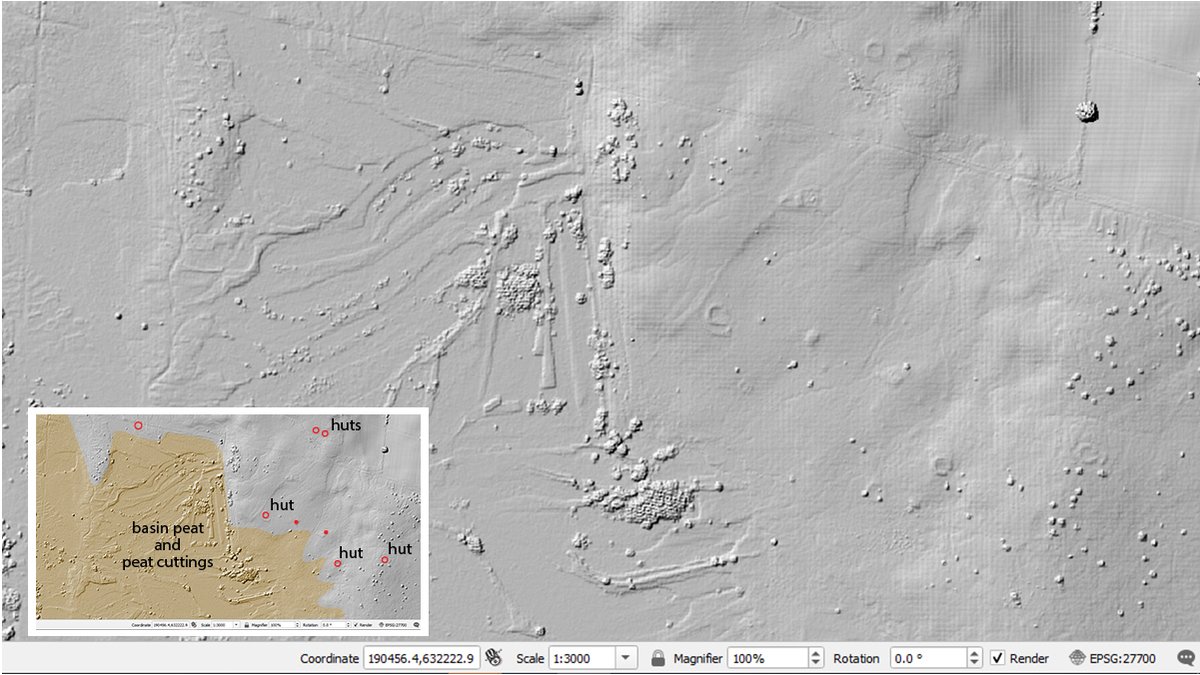

Animals, specifically cattle, were a significant part of the highland medieval economy. The cattle would graze in the outfield during the warm summer months and small huts, known as shielings, would be built, seasonally, for the those watching over the herd. 19/34

When it was time to sell the cattle, they would be walked to market. Drove roads leave a distinctive trace in the landscape. They are often very wide and create fans of multiple smaller tracks when passing through narrow passes. 20/34

Around 1750 the “improvements” see a change in land organisation. Rigs are enclosed into fields. The shape of the rigs were often preserved in the new boundaries but, the rigs themselves are abandoned. Where the new fields have been used as pasture the rigs often survive. 21/34

In areas of modern arable agriculture, traces of the rigs may survive in the field boundaries. 22/34

Around the same time, in the NW, crofts are installed over the earlier globular fields. The estates are planned on paper maps with the land subdivided with little respect for topography. Tenants are now leased strips. 23/34

The same principle of mapping and redesigning estates on paper can be seen in the lowlands. Regular grids of smallholdings show where tenants now rented land with a much longer lease. A long lease encouraged investing effort in draining and destoning land to improve yield. 24/34

Planned estates are easy to spot and are distinctive in that they often have a road that passes, centrally, from one end of the estate to the other. 27/34

Many ferm-touns were cleared from the mid 18th C to make way for sheep. This sometimes leaves distinctive scars. Here we see a wall built directly over a line of houses. Quite a statement! 28/34

Not far away, on the coast, we can see a short-lived settlement of newer houses clinging to the fringes before the people are finally cleared to the cities and New World. 29/34

This clearing of the land for sheep has also developed into shooting estates for hunting deer and grouse. The burning of the moor to create territories for grouse is particularly distinctive. These “empty” landscapes are seen as perfect for large forestry and wind power. 30/34

Technology and yield are the drivers for change in the modern lowland agricultural landscapes. Larger machines need larger fields so the change from our time will be the agglomeration of fields, so called “prairiefication”. 31/34

I hope I have piqued your interest. If you would like to read it all again you can find the whole thread here on my blog https://dairsieonline.co.uk/wordpress/2020/05/22/this-is-not-a-hillfort-post/">https://dairsieonline.co.uk/wordpress... 32/34

If you would like to learn more here are a few folk to follow. Top of the list is @DrSueOosthuizen. What she doesn’t know about landscapes isn’t worth knowing. For lidar, satellite and air photos start with @jost_hobic & @indyfromspace. 33/34

All the images in this thread has been produced using free online resources. The air photography shown is from Bing Maps https://www.bing.com/maps ;">https://www.bing.com/maps"... The lidar was downloaded from the https://remotesensingdata.gov.scot/ ">https://remotesensingdata.gov.scot/">... and viewed using QGIS https://qgis.org/en/site/ ">https://qgis.org/en/site/&... 34/34

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter