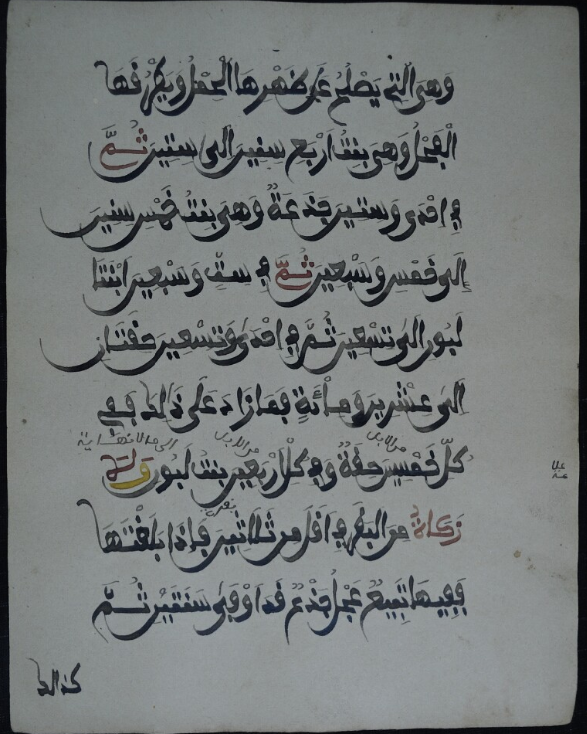

The @britishlibrary has digitized an absolute treasure trove of manuscripts from Djenné, Mali. This collection contains mostly Arabic manuscripts, generally written in the gorgeous Malinese substyle of the Maghrebi script.

One manuscript caught my eye...

https://eap.bl.uk/collection/EAP488-1">https://eap.bl.uk/collectio...

One manuscript caught my eye...

https://eap.bl.uk/collection/EAP488-1">https://eap.bl.uk/collectio...

Namely: a 1915 copy of the risālah by ibn ʾAbī Zayd al-Qayrawānī (d. 386/996) an instructional book on ablutions, prayer, fasting, alms-giving etc.

But what made it interesting to me, was not so much the contents, as the vocalisation of the text. https://eap.bl.uk/archive-file/EAP488-1-10-3">https://eap.bl.uk/archive-f...

But what made it interesting to me, was not so much the contents, as the vocalisation of the text. https://eap.bl.uk/archive-file/EAP488-1-10-3">https://eap.bl.uk/archive-f...

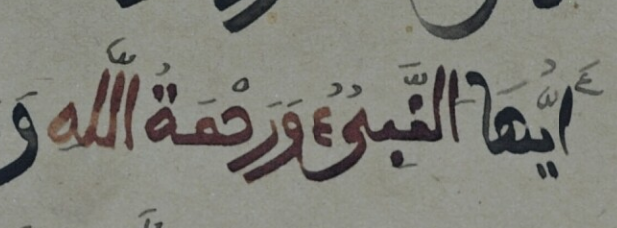

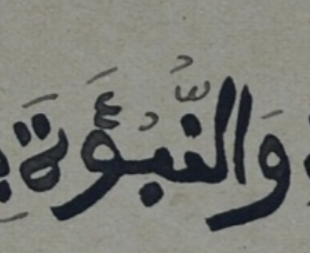

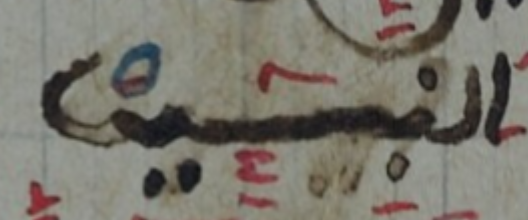

First, there is the use of the hamzah in words of the word "prophet", in standard Classical Arabic today, read as nabiyy "prophet", nubuwwah "prophecy", but in this manuscript occasionally show up as nabīʾ, nabīʾīna and nubūʾah.

This way of reading that word is typical in Quranic recitation among the transmitters of Nāfiʿ (primarily Warš and Qālūn). Nāfiʿ& #39;s reader was considered sunnah according to the Maliki school of jurisprudence (which is dominant in Northern Africa including Mali).

I recently wrote a short essay on this word nabīʾ, which has often been considered an incorrect hyperclassicism by scholars for rather bad reasons. You can read that here:

https://phoenixblog.typepad.com/blog/2020/04/anachronism-and-the-%CA%BFarabiyyah.html

Or">https://phoenixblog.typepad.com/blog/2020... listen to it here: https://youtu.be/Sb0egs5LGs8 ">https://youtu.be/Sb0egs5LG...

https://phoenixblog.typepad.com/blog/2020/04/anachronism-and-the-%CA%BFarabiyyah.html

Or">https://phoenixblog.typepad.com/blog/2020... listen to it here: https://youtu.be/Sb0egs5LGs8 ">https://youtu.be/Sb0egs5LG...

But now my interest was piqued: If there is such a piece of influence of the local Quranic recitation on the way this non-Quranic Classical Arabic manuscript is vocalised, can we find any other typical features of Warš ʿan Nāfiʿ in this manuscript? The answer is yes!

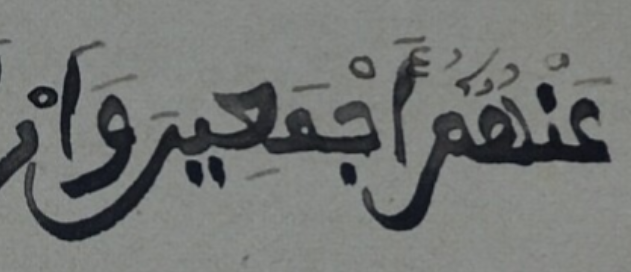

A typical feature of Warš is that he uses long versions of the plural pronouns when they stand in front of a hamzah. hum, -hum, -him, -kum, -tum, ʾantum become humū, -humū, etc.. An indeed, we find this here!

ʿanhumūū ʾaǧmaʿīna;

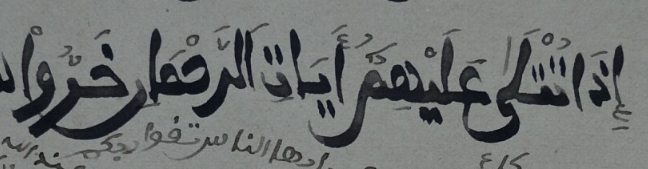

ʾiḏā tutlā ʿalayhimū ʾāyāt al-raḥmāni

ʿanhumūū ʾaǧmaʿīna;

ʾiḏā tutlā ʿalayhimū ʾāyāt al-raḥmāni

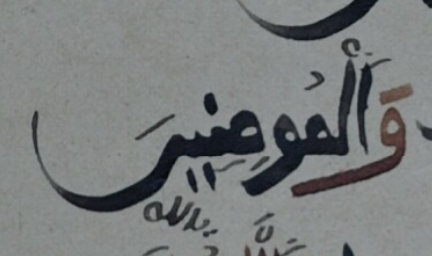

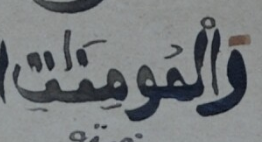

Another feature typical of Warš& #39;s reading is that he drops the hamzah if 1. it is the first root consonant of the word, and 2. a vowel precedes it. And indeed: al-mūminīn and al-mūmināt, but li-ruʾyati-hī.

A feature that is not unique to Warš, but typical for Quranic recitation (and in Quranic recitation, not even for all readers) is the stretching of a word-final long vowel if the next word starts with a hamzah (marked with maddah). We find this too!

fīī ʾummi

ʾiḏāā ʾaḥdaṯa

fīī ʾummi

ʾiḏāā ʾaḥdaṯa

Even when this involves a long vowel that is not written plene, it is written out:

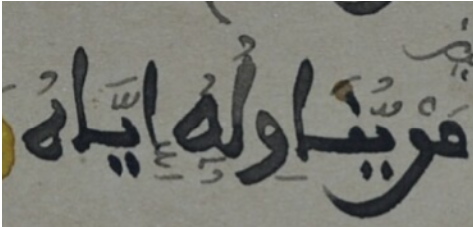

maỹyunāwilu-hūū ʾiyyā-hu

(notice also the assimilation the nūn of man to the next yāʾ being explicitly written with Šaddah).

maỹyunāwilu-hūū ʾiyyā-hu

(notice also the assimilation the nūn of man to the next yāʾ being explicitly written with Šaddah).

Some of these features (such as the warš-like lengthening of the pronouns, and the using of the hamzah on nabiyy) are not quite regular in this manuscript and you find the normal Classical form as well.

One is left wondering: did the scribe impose a warsh-like grammar while copying a classical manuscript; or was the original written with warsh-like grammar and did the scribe sometimes accidentally impose "standard Classical Arabic" upon the text?

Either way, the manuscript reveals something very interesting, it shows that as late as the 20th century (!) different opinions on which grammatical rules should be applied to a Classical Text were still not entirely established (at least in Mali).

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter