OK, I promise this is my last post about NATO history today (I do have a life outside reading documents!) But I just have to write about this because of what it shows about history, and the complexities that we, as historians, have to tackle.

I will discuss two memos to @BillClinton& #39;s National Security Adviser Antony Lake: one by @ARVershbow (but summarising not just his own views but those of Nick Burns and Dan Fried), and one by Richard Schifter, who submitted a separate opinion. The subject? @NATO enlargement.

On Oct. 4 Vershbow wrote to Lake summarising why the administration decided, a year earlier, to enlarge NATO. This was not to contain Russia but to promote democracy in Central and Eastern Europe. Here& #39;s the relevant paragraph (and the full doc is here: https://clinton.presidentiallibraries.us/items/show/57563).">https://clinton.presidentiallibraries.us/items/sho...

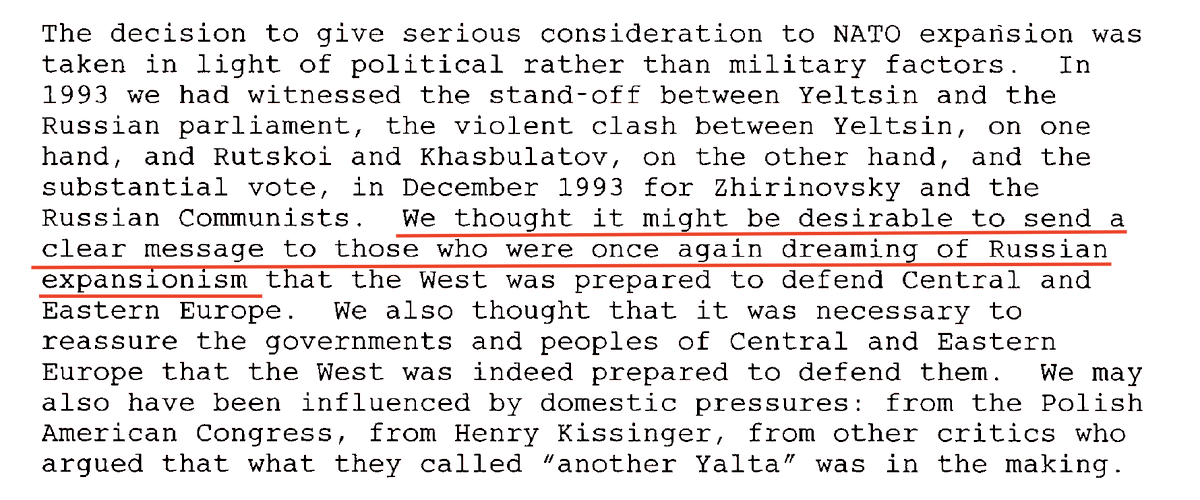

Schifter thought differently. He figured the enlargement agenda was driven primarily by fear of Russia& #39;s turn to nationalism. "We thought it might be desirable to send a clear message." Schifter implied enlargement was no longer imperative in 1994, now that Yeltsin won.

What I find remarkable here is that people on the NSC who were actually there a year earlier, could not now remember why the decision to enlarge NATO was made, or they had exactly opposite recollections on this account. People directly involved - and only after a few months!

What, then, can be said of us, approaching this subject a quarter of a century later? Do we believe @ARVershbow or Schifter? What if there is evidence supporting both points of view? (As there is in this case). The only safe thing here is to hedge and resort to multi-causality.

In a sense, this is simply to acknowledge the complexity of the situation. In another sense, this is also to acknowledge our inability, as historians, to really get to the bottom of it. It& #39;s a Rashomon-type dilemma I face daily while reading these documents.

That& #39;s why I find debates about what constitutes "falsified" history, and what doesn& #39;t so disturbing. As historians, we can easily agree that something either happened or it didn& #39;t. But once we get to interpretations of why something happened, there& #39;s just a swamp out there.

Yet like E.H. Carr, we should still be able to distinguish good history from bad history, and by "we," I mean the epistemic community of professional historians, where so much hinges on recognition and reputation. Sorry I have to conclude with a platitude but that& #39;s where we are.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter